Download-STRUC OF LIPIDS PROTEINS AND NUCLIEC ACID

advertisement

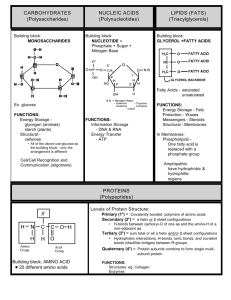

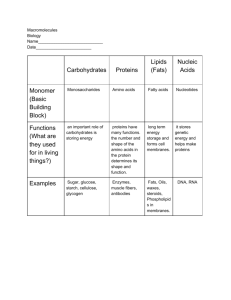

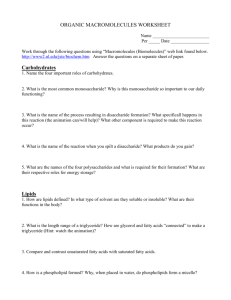

The Molecules of Life • Within cells, small organic molecules are joined together to form larger molecules • Macromolecules are large molecules composed of thousands of covalently connected atoms Most macromolecules are polymers, built from monomers • A polymer is a long molecule consisting of many similar building blocks called monomers • Three of the four classes of life’s organic molecules are polymers: – Carbohydrates – Proteins – Nucleic acids The Synthesis and Breakdown of Polymers • Monomers form larger molecules by condensation reactions called dehydration reactions • Polymers are disassembled to monomers by hydrolysis, a reaction that is essentially the reverse of the dehydration reaction Short polymer Unlinked monomer Dehydration removes a water molecule, forming a new bond Longer polymer Dehydration reaction in the synthesis of a polymer Hydrolysis adds a water molecule, breaking a bond Hydrolysis of a polymer The Diversity of Polymers • Each cell has thousands of different kinds of 1 2 3 macromolecules H HO • Macromolecules vary among cells of an organism, vary more within a species, and vary even more between species • An immense variety of polymers can be built from a small set of monomers Lipids are a diverse group of hydrophobic molecules • Lipids are the one class of large biological molecules that do not form polymers • The unifying feature of lipids is having little or no affinity for water • Lipids are hydrophobic because they consist mostly of hydrocarbons, which form nonpolar covalent bonds • The most biologically important lipids are fats, phospholipids and steroids Fats • Fats are constructed from two types of smaller molecules: glycerol and fatty acids • Glycerol is a three-carbon alcohol with a hydroxyl group attached to each carbon • A fatty acid consists of a carboxyl group attached to a long carbon skeleton Fatty acid (palmitic acid) Glycerol Dehydration reaction in the synthesis of a fat • Fats separate from water because water molecules form hydrogen bonds with each other and exclude the fats • In a fat, three fatty acids are joined to glycerol by an ester linkage, creating a triacylglycerol, or triglyceride Ester linkage Fat molecule (triacylglycerol) • Fatty acids vary in length (number of carbons) and in the number and locations of double bonds • Saturated fatty acids have the maximum number of hydrogen atoms possible and no double bonds • Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds • The major function of fats is energy storage (a) Saturated fat Structural formula of a saturated fat molecule Space-filling model of stearic acid, a saturated fatty acid (b) Unsaturated fat Structural formula of an unsaturated fat molecule Space-filling model of oleic acid, an unsaturated fatty acid Double bond causes bending. • Fats made from saturated fatty acids are called saturated fats • Most animal fats are saturated • Saturated fats are solid at room temperature • A diet rich in saturated fats may contribute to cardiovascular disease through plaque deposits Stearic acid Saturated fat and fatty acid. • Fats made from unsaturated fatty acids are called unsaturated fats • Plant fats and fish fats are usually unsaturated • Plant fats and fish fats are liquid at room temperature and are called oils Oleic acid cis double bond causes bending Unsaturated fat and fatty acid. Phospholipids • In a phospholipid, two fatty acids and a phosphate group are attached to glycerol • The two fatty acid tails are hydrophobic, but the phosphate group and its attachments form a hydrophilic head Hydrophilic head Hydrophobic tails Choline Phosphate Glycerol Fatty acids (a) Structural formula Hydrophilic head Hydrophobic tails (b) Space-filling model (c) Phospholipid symbol (d) Phospholipid bilayer • When phospholipids are added to water, they selfassemble into a bilayer, with the hydrophobic tails pointing toward the interior • The structure of phospholipids results in a bilayer arrangement found in cell membranes • Phospholipids are the major component of all cell membranes Hydrophilic head Hydrophobic tails WATER WATER Steroids • Steroids are lipids characterized by a carbon skeleton consisting of four fused rings • Cholesterol, an important steroid, is a component in animal cell membranes • Although cholesterol is essential in animals, high levels in the blood may contribute to cardiovascular disease Proteins have many structures, resulting in a wide range of functions • Proteins account for more than 50% of the dry mass of most cells • Protein functions include structural support, storage, transport, cellular communications, movement, and defense against foreign substances • Enzymes are a type of protein that acts as a catalyst, speeding up chemical reactions • Enzymes can perform their functions repeatedly, functioning as workhorses that carry out the processes of life Substrate (sucrose) Glucose Enzyme (sucrose) Fructose Defensive proteins Function: Protection against disease Example: Antibodies inactivate and help destroy viruses and bacteria. Antibodies Virus Bacterium Storage proteins Function: Storage of amino acids Examples: Casein, the protein of milk, is the major source of amino acids for baby mammals. Plants have storage proteins in their seeds. Ovalbumin is the protein of egg white, used as an amino acid source for the developing embryo. Ovalbumin Amino acids for embryo Transport proteins Function: Transport of substances Examples: Hemoglobin, the iron-containing protein of vertebrate blood, transports oxygen from the lungs to other parts of the body. Other proteins transport molecules across cell membranes. Transport protein Cell membrane Hormonal proteins Function: Coordination of an organism’s activities Example: Insulin, a hormone secreted by the pancreas, causes other tissues to take up glucose, thus regulating blood sugar concentration. High blood sugar Insulin secreted Normal blood sugar Receptor proteins Function: Response of cell to chemical stimuli Example: Receptors built into the membrane of a nerve cell detect signaling molecules released by other nerve cells. Receptor protein Signaling molecules Structural proteins Function: Support Examples: Keratin is the protein of hair, horns, feathers, and other skin appendages. Insects and spiders use silk fibers to make their cocoons and webs, respectively. Collagen and elastin proteins provide a fibrous framework in animal connective tissues. Collagen Connective tissue 60 m Polypeptides • Polypeptides are polymers of amino acids • A protein consists of one or more polypeptides Amino Acid Monomers • Amino acids are organic molecules with carboxyl and amino groups • Amino acids differ in their properties due to differing side chains, called R groups • Cells use 20 amino acids to make thousands of proteins a carbon Amino group Carboxyl group Nonpolar side chains; hydrophobic Side chain (R group) Glycine (Gly or G) Methionine (Met or M) Alanine (Ala or A) Valine (Val or V) Phenylalanine (Phe or F) Leucine (Leu or L) Tryptophan (Trp or W) Isoleucine (le or ) Proline (Pro or P) Polar side chains; hydrophilic Serine (Ser or S) Threonine (Thr or T) Cysteine (Cys or C) Tyrosine (Tyr or Y) Asparagine (Asn or N) Glutamine (Gln or Q) Electrically charged side chains; hydrophilic Basic (positively charged) Acidic (negatively charged) Aspartic acid Glutamic acid (Asp or D) (Glu or E) Lysine (Lys or K) Arginine (Arg or R) Histidine (His or H) Amino Acids Essential amino acids: An essential amino acid for an organism is an amino acid that cannot be synthesized by the organism from other available resources, and therefore must be supplied as part of its diet. Most of the plants and microorganism cells are able to use inorganic compounds to make amino acids necessary for the normal growth. Eight amino acids are generally regarded as essential for humans: tryptophan, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, valine, leucine, isoleucine. Two others, histidine and arginine are essential only in children. A good memonic device for remembering these is "Private Tim Hall", abbreviated as: PVT TIM HALL: Phenylalanine, Valine, Tryptophan Threonine, Isoleucine, Methionine Histidine, Arginine, Lysine, Leucine Use of Amino Acids • Aspartame (aspartyl-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester) is an artificial sweetener. • 5-HTP (5-hydroxytryptophan) has been used to treat neurological problems associated with PKU (phenylketonuria), as well as depression. • Monosodium glutamate is a food additive to enhance flavor. Amino Acid Polymers • Amino acids are linked by peptide bonds • A polypeptide is a polymer of amino acids • Polypeptides range in length from a few monomers to more than a thousand • Each polypeptide has a unique linear sequence of amino acids • Each polypeptide has a unique linear sequence of amino acids, with a carboxyl end (C-terminus) and an amino end (N-terminus) Peptide bond New peptide bond forming Side chains Backbone Amino end (N-terminus) Peptide bond Carboxyl end (C-terminus) Protein Conformation and Function • A functional protein consists of one or more polypeptides twisted, folded, and coiled into a unique shape • The sequence of amino acids determines a protein’s three-dimensional conformation • A protein’s conformation determines its function Antibody protein Protein from flu virus Four Levels of Protein Structure • The primary structure of a protein is its unique sequence of amino acids • Secondary structure, found in most proteins, consists of coils and folds in the polypeptide chain • Tertiary structure is determined by interactions among various side chains (R groups) • Quaternary structure results when a protein consists of multiple polypeptide chains Secondary structure Tertiary structure Quaternary structure Transthyretin polypeptide Transthyretin protein a helix pleated sheet • Primary structure, the sequence of amino acids in a protein, is like the order of letters in a long word • Primary structure is determined by inherited genetic information Primary structure Amino acids 1 10 5 Amino end 30 35 15 20 25 45 40 50 Primary structure of transthyretin 65 70 55 60 75 80 90 85 95 115 120 110 105 100 125 Carboxyl end • The coils and folds of secondary structure result from hydrogen bonds between repeating constituents of the polypeptide backbone • Typical secondary structures are a coil called an alpha helix and a folded structure called a beta pleated sheet Secondary structure a helix pleated sheet Hydrogen bond strand Hydrogen bond Tertiary structure Transthyretin polypeptide Hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals interactions Polypeptide backbone Hydrogen bond Disulfide bridge Ionic bond Quaternary structure Transthyretin protein • Quaternary structure results when two or more polypeptide chains form one macromolecule • Hemoglobin is a globular protein consisting of four polypeptides: two alpha and two beta chains α-Keratin • α-Keratin is a tough fibrous protein found in humans and other mammals (hair, horns, wool, nails). • * It is a helix of helices and is described as a coiled coil. • * The basic structure has a pair of right-handed α-helices wound around one another in a left-handed twist to form super-twisted coiled coil) • * It has a repeating structure that is rich in the amino • acids Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Met, and Phe. • * Structure is cross-linked and stabilized by disulfide • bonds. Note that β-keratin (found in the feathers, scales, beaks, claws of birds/reptiles) rather has a stacked β sheet structure, and is tougher than α-Keratin. Polypeptide chain Chains Iron Heme Polypeptide chain Collagen a Chains Hemoglobin Sickle-Cell Disease: A Simple Change in Primary Structure • A slight change in primary structure can affect a protein’s conformation and ability to function • Sickle-cell disease, an inherited blood disorder, results from a single amino acid substitution in the protein hemoglobin 10 µm Red blood Normal cells are cell shape full of individual hemoglobin molecules, each carrying oxygen. 10 µm Red blood cell shape Fibers of abnormal hemoglobin deform cell into sickle shape. Figure 3.22 Sickle-cell Normal Primary Structure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Secondary and Tertiary Structures Quaternary Structure Function Normal hemoglobin subunit a Molecules do not associate with one another; each carries oxygen. a 5 m Exposed hydrophobic region Sickle-cell hemoglobin a subunit Red Blood Cell Shape Molecules crystallized into a fiber; capacity to carry oxygen is reduced. a 5 m What Determines Protein Conformation? • In addition to primary structure, physical and chemical conditions can affect conformation • Alternations in pH, salt concentration, temperature, or other environmental factors can cause a protein to unravel • This loss of a protein’s native conformation is called denaturation • A denatured protein is biologically inactive Denaturation Normal protein Denatured protein Renaturation The Protein-Folding Problem • It is hard to predict a protein’s conformation from its primary structure • Most proteins probably go through several states on their way to a stable conformation • Chaperonins are protein molecules that assist the proper folding of other proteins Cap Hollow cylinder Chaperonin (fully assembled) Polypeptide Steps of Chaperonin Action: An unfolded polypeptide enters the cylinder from one end. Correctly folded protein The cap attaches, causing the cylinder to change shape in such a way that it creates a hydrophilic environment for the folding of the polypeptide. The cap comes off, and the properly folded protein is released. • Scientists use X-ray crystallography to determine a protein’s conformation X-ray diffraction pattern Photographic film Diffracted X-rays X-ray source X-ray beam Crystal Nucleic acid X-ray diffraction pattern 3D computer model Protein Nucleic acids store and transmit hereditary information • The amino acid sequence of a polypeptide is programmed by a unit of inheritance called a gene • Genes are made of DNA, a nucleic acid The Roles of Nucleic Acids • There are two types of nucleic acids: – Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) – Ribonucleic acid (RNA) • DNA provides directions for its own replication • DNA directs synthesis of messenger RNA (mRNA) and, through mRNA, controls protein synthesis • Protein synthesis occurs in ribosomes DNA Synthesis of mRNA in the nucleus mRNA NUCLEUS CYTOPLASM mRNA Movement of mRNA into cytoplasm via nuclear pore Ribosome Synthesis of protein Polypeptide Amino acids The Structure of Nucleic Acids • Nucleic acids are polymers called polynucleotides • Each polynucleotide is made of monomers called nucleotides • Each nucleotide consists of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate group • The portion of a nucleotide without the phosphate group is called a nucleoside 5 end Sugar-phosphate backbone (on blue background) Nitrogenous bases Pyrimidines 5C 3C Nucleoside Nitrogenous base Cytosine (C) Thymine (T, in DNA) Uracil (U, in RNA) Purines 5C Phosphate group 3C Sugar (pentose) Adenine (A) Guanine (G) (b) Nucleotide 3 end Sugars (a) Polynucleotide, or nucleic acid Deoxyribose (in DNA) (c) Nucleoside components Ribose (in RNA) 5 end Nucleoside Nitrogenous base Phosphate group Nucleotide 3 end Polynucleotide, or nucleic acid Pentose sugar 5 3 3 5 Sugar-phosphate backbones Hydrogen bonds Base pair joined by hydrogen bonding Nucleotide Monomers • Nucleotide monomers are made up of nucleosides and phosphate groups • Nucleoside = nitrogenous base + sugar • There are two families of nitrogenous bases: – Pyrimidines have a single six-membered ring – Purines have a six-membered ring fused to a five-membered ring • In DNA, the sugar is deoxyribose • In RNA, the sugar is ribose Nitrogenous bases Pyrimidines Cytosine C Thymine (in DNA) Uracil (in RNA) U T Purines Adenine A Guanine G Pentose sugars Deoxyribose (in DNA) Nucleoside components Ribose (in RNA) Nucleotide Polymers • Nucleotide polymers are linked together, building a polynucleotide • Adjacent nucleotides are joined by covalent bonds that form between the –OH group on the 3´ carbon of one nucleotide and the phosphate on the 5´ carbon on the next • These links create a backbone of sugar-phosphate units with nitrogenous bases as appendages • The sequence of bases along a DNA or mRNA polymer is unique for each gene The DNA Double Helix • A DNA molecule has two polynucleotides spiraling around an imaginary axis, forming a double helix • In the DNA double helix, the two backbones run in opposite 5´ to 3´ directions from each other, an arrangement referred to as antiparallel • One DNA molecule includes many genes • The nitrogenous bases in DNA form hydrogen bonds in a complementary fashion: A always with T, and G always with C 5 end 3 end Sugar-phosphate backbone Base pair (joined by hydrogen bonding) Old strands Nucleotide about to be added to a new strand 5 end New strands 5 end 3 end 5 end 3 end DNA and Proteins as Tape Measures of Evolution • The linear sequences of nucleotides in DNA molecules are passed from parents to offspring • Two closely related species are more similar in DNA than are more distantly related species • Molecular biology can be used to assess evolutionary kinship