'the sovereignty of its sharing': Jean

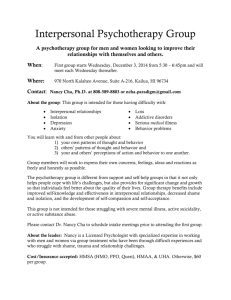

advertisement

As the ‘sovereignty of its sharing’; Jean-Luc Nancy and the politics of lost authority. Samuel Kirwan School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom Samuel.kirwan@bristol.ac.uk As the ‘sovereignty of its sharing’; Jean-Luc Nancy and the politics of lost authority This article addresses how the work of the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy might inform our understanding of changes to policing and the law introduced under the 'Community Safety' agenda and more specifically under the term 'AntiSocial Behaviour'. Having set out the 'governmentality' approach to this field it argues that what is missing from these accounts is an attention to authority; specifically the question of what it means to have lost authority, following Hannah Arendt's claim that authority transcends the exercise of power. The article proceeds by detailing Nancy's approach to politics, authority and community in its re-working of Arendtian themes. Such an approach, I argue, gives an alternative reading of how 'communitarian' ideas were represented in these initiatives, and in particular how they were integrated into the criminal law. The article concludes with a set of questions around which we might orientate a politics of community, one that would be both critical of these changes as well as retaining a productive and transformative approach. The key to such a balance, the article argues, lies in inscribing an authority as community, rather than 'of' or 'against' it. Keywords: community; Jean-Luc Nancy; authority; governmentality As ‘the sovereignty of its sharing’: Jean-Luc Nancy and the politics of lost authority Introduction Such behaviour is not being effectively checked by the community as a whole with the backing of the police. I have in mind, for example, graffiti and criminal damage. Those involved drift into disorder and drift further into crime. (Jack Straw, speech to commons 14th November 1997, shortly before the introduction of the Anti-Social Behaviour Order (ASBO) in the Crime and Disorder Bill) It’s time to move beyond the ASBO. We need a complete change in emphasis, with communities working with the police and other agencies to stop bad behaviour escalating that far. (Theresa May, speech at Coin Street Community Centre, 28th June 2010) Like many, such a juxtaposition displays the repetition of ‘New Labour’ themes, promises and aspirations in the first months of ‘coalition’ government. That the latter dream of a perfect co-operation between the community and the police, ensuring a locally produced authority that would guarantee the moral formation of its citizens, would one day be represented as a radical shift from the Anti-Social Behaviour Order would no doubt have proved a shock to the Straw of 1997. Yet he need not have worried; the proposed vehicle for this ‘move beyond’, the ‘Crime Prevention Injunction’, with its promise to be “less bureaucratic” and as such “speedier’ and ‘more effective” (Brokenshire, 2011), holds rigidly to the anti-statist tendency within criminal justice reform for which, in the 1990s and 2000s, ‘Community Safety’ was the established term. This article follows Nikolas Rose in recognising this tendency to display the orientation of Western neo-liberal democracies (principally the United States and United Kingdom) towards “governing through community” (1999:192). Yet while Rose’s primary focus therein is upon a distributed appeal to the ethical self – an ‘ethicopower’ – the article examines a different aspect of this form of governing described by Rose, namely the discursive foregrounding of the lost authority of the state, and its accompanying project for authority to be returned to the community. In this change of emphasis, the article seeks to respond to certain blind spots within Rose’s engagement of this dynamic, most importantly to the lack of analysis of the nature of authority. Through the concept of a ‘politics of lost authority’ I describe the pressing question of this ‘government through community’ to be less the enticement of the ethical subject than the drive to fill the loss of community with close-knit, neighbourly relationships that would regulate behaviour in a more ‘intimate’ manner. This shift of emphasis demands not only a reappraisal of community and authority, but also of political action. The aim of the article is to provide a response to the failure within ‘governmentality’ studies to articulate a political approach to the terrain of community empowerment and behavioural interventions beyond the negativity of critique. The rejoinder posed however is drawn not from the communitarian tracts of which Rose and others are directly critical, but from the work of Jean-Luc Nancy (1991, 1993, 1997, 2000; Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy, 1997a, 1997b), alluded to without being fully explored in Rose’s work (1999:195). I explore how Nancy’s approach both re-configures our understanding of what is at stake in these political developments and allows for the articulation, albeit in a very different form, of an alternative political practice of community. Nancy’s work is presented in the article through its re-working of two critical problematics taken from the work of Hannah Arendt; the exhaustion of the political as a distinct sphere and the analogous exhaustion of authority as a specific modality of power. Having presented Rose’s narrative and its relevance to the field of Community Safety in Section 1, these separate considerations, of the political and of authority, are explored in Sections 2 and 3, with the common form of Nancy’s reframing of these Arendtian themes being presented through the concepts of ‘retreat’, ‘unworking’ and ‘interruption’. Having explored these re-workings of politics, authority and community in Nancy’s work, the article argues that a different understanding emerges of the manner in which, through the ‘communitarian’ accounts of Amitai Etzioni and others, the law is made to ‘represent’ the community. Casting these accounts as an attempt to ‘hypostatise’ the excessive moment of subject formation, it argues that what is at stake in the ‘Community Safety’ agenda is the closure of community as it is present in the criminal law. Describing these socio-historical descriptions as articulations of the ‘politics of lost authority’, the article argues that the demand emerging from Nancy’s work is to contest the desire for an intimate, or ‘immanent’, authority created and executed within the community, instead inscribing the very failure of the community to guarantee the morals of its members through an interruption or disruption of the ‘immanent figure’ such an ‘immanent authority’ implies. In a context in which authority has become the terrain for the closure of the ‘intimate exteriority’ (Levett, 2005:430) community is, it is in the name of another authority that this opposition must be formed. Section 1: The politics of lost authority As the term ‘community’ has become increasingly prominent in public discourse, the ‘governmentality’ canon has provided a compelling and widely circulated critique of its tactical and strategic deployment. This critique centres on the extent to which, as a direct result of its suggestion otherwise, community is intertwined with power, and is operative in maintaining certain circuits of inclusion and exclusion. We will begin by examining the historico-theoretical basis for this critique as it was elaborated in Foucault’s (1991) short lecture on ‘governmentality’, and how it has been applied to community in the work of Nikolas Rose (1999). As a portmanteau for ‘governmental rationality’, the term governmentality describes an “art of government” (Foucault, 1991:97) focused not upon rule but upon the channelling and distribution of subjects’ own self-management practices; in short, upon ‘the conduct of conduct’. Its increasing use as a critical analytic is due to the emergence in the 1990s of an ‘Anglo neo-Foucauldian’ governmentality studies (see Rose, 1999, Dean, 1999), for which the concept captured with particular acuity the modes of ‘hollowed-out’ governance particular to the ‘neo-liberal’ or ‘New Right’ reforms begun in the Reagan and Thatcher eras, and their continuation in the centre-left administrations of the ‘New Democrats’ and ‘New Labour’. In Foucault’s (1991) account, as a historical moment governmentality defines a dissolution, “from the middle ages to the 16th century” (134), of “the constants of sovereignty” (143). For this ‘art of government’, enacted through various knowledges for managing particular spheres of activity, progressively destabilised the division between the governors and the governed located in the authority of the sovereign figure. Governmental objectives were achieved not through direct sovereign intervention into governed subjects, but through the constitution of the ‘governed’ as a population to be shaped by these emergent bodies of knowledge. Thus Foucault noted how the division proper to sovereign rule was superseded by an increasingly complex field of governmental techniques, one in which the population was simultaneously an objective and a space of intervention (102). As the term for this shift, ‘governmentality’ designates the saturation of the political by strategies and techniques for the improvement of the productivity, wealth, longevity and health of the population. To use the form of list typical to the contemporary governmentality approaches, the terrain of government is henceforth the operation of “programmes, strategies, tactics, devices, calculations, negotiations, intrigues, persuasions and seductions” (Rose, 1999:5). In ‘governing through community’, then, we are dealing not with a direct imposition of community policies, discourses and directives upon a subjected populace, but a specific arrangement of this socio-technical terrain in which ‘community’ is a kind of conceptual locus. The starting point for any analysis of this field, inasmuch as it designates the transition of this concept into politics, or its being bestowed a certain governmental force, is the turn, by both the ‘New Democrats’ and ‘New Labour’, to ‘communitarian’ social philosophies, most notably that articulated by Amitai Etzioni (1995, 1998). While on a substantive level the existence of anything resembling an ‘Etzionian’ policy has been questioned (Hale, 2006), Rose is concerned with the manner in which Etzioni’s focus upon the production of morals and values in the community, in collaboration with Robert Putnam’s (2001) foregrounding of civic participation as the site for the renewal of community, translated into a new programmes, strategies and devices for enticing individuals towards a certain responsibility of conduct. As the incorporation into government of such profoundly personal moments of ethical self- formation, ‘governing through community’ operates, Rose argues, through an ‘ethicopower’; a “micro-management” of subjects’ own “self-steering practices” (1999:193). Now, at the time Rose was writing, the concept of ‘Community Safety’ was fully established as a powerful critique of the management of behaviour by the state and the criminal justice system traditionally conceived. Central to this critique was an observation, articulated by the same communitarian authors, on the lost authority of the community in the context of behavioural decline (see Reiner, 2007). The sociohistorical accounts of Etzioni, Putnam, Alisdair MacIntyre (1997) and others sought to situate the rising levels of crime in the 1960s and 70s as part of a historical decline of the community, and as such of its capacity to guarantee the morality of its members. In short, the need to affirm the community, and to re-model the functions of the state in its image, was driven by the very failure of the community as an effective moral authority. In line with this thinking, the basis of Community Safety was the proposition that crime and anti-social behaviour are to be combated through a greater level of communal authority;1 a tightening of relational control, through a range of interventionary powers, over the process of subject-formation. Rose’s focus in this respect is upon how certain ‘authorities of conduct’ have quietly assumed a dominant position within contemporary politics (1999: 187). It is a questioning that finds resonance with the wider critique of community in which its ‘gated’ form is taken as emblematic of the exclusionary tactics that lie at the heart of all 1 The major recommendation of the Morgan Report (The Home Office, 1991), through which the term was given national prominence, was that crime prevention be considered a task for all in the community (3). community practices (Bauman, 2004). Yet such critical perspectives fail to ask of how authority itself is being changed in these initiatives. For what constitutes a breach of the injunctive powers through which Community Safety was enacted, whether Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, Dispersal Orders or others, is a breach of rules set out by the individual order, rather than a breach of the law itself as it is applied universally. It is as such not a breach of the formal structure that applies to all but of an interdiction particular to that person or population, created, in the terms set out in the Crime and Disorder Act (Great Britain, 1998:§1b) in which the Anti-Social Behaviour Order was introduced, for the necessity of protecting those in the community from any further harm. As Deleuze (1992:3) recognised, such forms of intervention are contracts from which one can never leave; they preclude, in other words, any situated questioning or contestation of their structure. It is this particular aspect of New Labour’s community program, namely the focus upon a community authority to be exercised through more supple and responsive powers, that has been taken up by the current government under the name ‘The Big Society’. For it is the argument of Phillip Blond, the principle thinker behind this concept, that this focus upon strengthening the authority of the community was little more than an undercurrent within New Labour’s community policy (Blond, 2009:§3), whose focus, in concepts such as ‘The Active Community’ (ACU, 1999), was always the individual; enticing, seducing and forcing that individual into community participation. Indeed the most important step to be taken in this direction, one being explored by the current coalition government, would be to significantly broaden the bodies who can apply for the above described injunctive powers (Brokenshire, 2011), currently available only to the police and social landlords. In sum the politics described here in its difference from ‘ethico-power’ bears three key characteristics; first the loss of community is presented as a grounding truth, second its filling in by the newly empowered intimate relationships of the local is offered as the immediate prescription, and third the product of this politics is a closure of questioning regarding forms of intervention. At the risk of adding another label to a burgeoning field, I wish to identify in this threefold form a ‘politics of lost authority’. Now, on a purely substantive level Rose’s critique of the enticement of ethical subjects, and the new authorities through which these tactics are routed, is poorly equipped to deal with the very abandonment, in favour of close-knit communities, of the same individuals within the Community Safety agenda and to a greater extent in ‘the Big Society’. Indeed, such critiques have been incorporated into contemporary invectives against New Labour’s community policy (see Cameron, 2009). More importantly however, in its closure of contestation, the form of authority in question here demands a political approach offering not only a critique of its manifestations, but a questioning of what political action and authority are. For the critique of community, in its clearing away of any questioning of what it means to live and act together, precludes investigation of community in its very transgressive and disruptive presence. If political action is reduced to capacities to form shared structures, and authority to the capacity to direct them, our critical languages remain not only powerless to contest the gradual closure of political contestation, but may also contribute to its encroaching dominance. To affirm community not as the intimacy of these tight-knit relationships, but as the very contestation of this intimacy, is to articulate the possibility of another political practice, and of another authority, against this ‘politics of lost authority’. The remainder of this article is given to articulating how such a perspective is offered in the work of Jean-Luc Nancy. We turn first to the question of politics, looking at how Nancy’s collaborative work with Philippe LacoueLabarthe re-framed Hannah Arendt’s thoughts on the nature of political action. An alternative politics Thus the argument of this article is that to articulate a political alternative to the terrain of political saturation and ‘government through community’, we must begin from Hannah Arendt’s (1998) observation on the misunderstanding of political action that subtends much of modern political philosophy, and of the sovereign authority to which this action is directed. Arendt draws our attention to the difference between a political stage, and sovereign authority, derived from a transcendent ‘outside’, and that for which we have retained these terms yet which correspond to something else entirely; an exercise of power proper to this management of the population through technical arrangements. Arendt lays out, through this explication, a major critique of the presumption that the answer to a destructive politics of community would be a more egalitarian or humane arrangement of the political or authoritative basis that underpins it. For what Nancy’s continuation of Arendt’s work demonstrates is that there can be no re-making or re-treating of this absented political stage or sovereign authority, or rather that any such attempt will only lead to the closure of the originary relationality of being; the presupposition through which we must re-configure our understanding of ‘community’. An alternative politics, on Nancy’s account, must be formed from an alternative orientation to this ‘end’ or ‘exhaustion’ of sovereign authority, one whose starting point would be the Heideggerian concept of Destruktion (and as such the whole analytic of deconstruction). This would be a political practice that, in laying bare the positive possibilities of a tradition in its historical construction, would expose it in its contingency. Yet, as Sparks (1997) notes, it is what might be created by Destruktion/deconstruction, rather than its critical purchase, that fascinates Nancy. For Destruktion, as a repetition of what is possible, is an act of repetition that opens onto an unknown, for; “[t]he repetition of the gestures through which philosophy reaches the point of its own exhaustion is the gesture ... by which philosophy can be made to release its unthought” (15). The manner in which this ‘release’ might be articulated as an alternative politics of community will be detailed across the course of the article. What is being argued is that, when transposed to the end or exhaustion of political authority in ‘Community Safety’ interventions, a political alternative is to be found in the ‘holding open’ of the very withdrawal of meaning that forms the condition for this exhaustion, and that, in a final movement, this exposure to contingency is to be described as the community. Each of these stages are to be addressed in turn; the ‘saturation’ of the political as it is detailed in Arendt and Nancy, the delineation of ‘authority’ drawn by these same authors, and the description of an ‘inoperative’ community that would be the very formation of authority and the social. The oikos, and its retreat Published in 1958, Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (1998) presented, through a return to the public realm of political debate (polis) in ancient Greece, a radical rethinking of the political, highlighting a constitutive misunderstanding of the term at the heart of Western thinking. For the polis, and its corresponding subject (zoon politikon), were concerned not with controlling and organizing the population, but with the entirely separate practice of free debate. Participation in the polis was “freely chosen” (13); it was as a sphere emptied of that necessity of governance proper to the household (oikos). Yet blurrings of this division between the oikos and the polis began to take hold with the equation, in the Roman era, of the management of the household with the management of the state; the good paterfamilias with the good King (27). The expropriations of the peasant classes following the Reformation, and the accompanying loss of meaning of private property,2 in further erasing the originary division between public and private, brings this blurring to a full close, as the form of behaviour pertaining to the household, the caring for and management of the life process (social life), “has become the standard for all regions of life” (45). Man is no longer zoon politikon but animal laborans; an entity occupied primarily with the material necessities of life, whose accelerative growth under consumer capitalism, within which even items for use become items for consumption, has outstripped any attachment to ‘natural’ necessity (124). Society, in this state of saturation, is a denuded terrain, comprised not of plurality, and the capacity for a public stage that would bring together free men in their constitutive differences, but a flattened terrain in which singular man makes choices between technical options. For Arendt holds, as Dana Villa notes, “the strongest 2 Arendt notes another modern confusion here between wealth and property (1998:65-6). possible conviction that our reality is one in which stable boundaries and distinctions have been dissolved and rendered virtually impossible” (1992:302). Now, at several points in Nancy’s oeuvre, Arendt’s illumination of the oikos and its saturation of the political space has returned as a central organising problematic. For Arendt poses the question, itself inexhaustible, of how we are to define a political agenda, or political philosophy, when political argument and political meaning appear to ‘withdraw’ before our very eyes. In other words, how is a political philosophy to be outlined when any ‘political’ problem is integrated into the social economy of necessity? It is this nagging flaw that for Nancy as for Arendt defines the stakes of philosophical thought and political intervention. While following Arendt’s delineation of this ‘saturation thesis’ however, Nancy will seek to give this ‘withdrawal’ of the political a double meaning (a doubling present in the term retreat/re-treat), defining both the exhaustion of the political and the political itself. Nowhere is Nancy’s debt to Arendt stronger than in his early collaborative works with Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe on the ‘retreat’ of the political, describing “the total immanence or the total immanentisation of the political in the social” (1997b:115). Here, like Arendt, they observe ‘politics’ to be the play of discourses and techniques which eradicate the political as a specific sphere, thus neutralising the possibility of true political dialogue. They recognise the ‘victory of animal laborans’ and the saturation of the public space by the socio-technical concerns of ‘management’ and ‘efficiency’ to be the defining questions for contemporary political theory (129) (the third key question, discussed in more detail below, concerns the loss of authority). The use of ‘immanentisation’ in favour of ‘immanence’ is, however, instructive, for seeking to open a contrast to Arendt they describe the ‘end’ or ‘exhaustion’ of politics, and this ‘loss of authority’, as itself the site through which the ‘political’ as such might be approached. This is indicated in their claim, pace Arendt, that “what drew back perhaps itself never took place” (131). While this is not the space to pursue such a discussion, it is questionable whether this is an adequate reading of Arendt, it being the latter’s problematisation of political ‘action’, given the originary plurality of ‘men’, that lays the ground for this re-working of the ‘political’.3 Indeed, rather than a critique of Arendt, Nancy’s approach might instead be seen as an attempt to pursue her analysis of the oikos in a mode proper to this emphasis upon plurality. For in actively reclaiming these Arendtian themes, Nancy’s work may instead be seen as a problematisation of the assumption, widely made, that as The Human Condition explores in a more or less positive fashion the role of the polis, it must be an argument for actively restoring a deliberative form of democratic action in the present (see for example Elster, 2002:15-16). For the polis, Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy argue, is not to be taken as a ‘past’ to be imagined and, in whatever limited fashion, recuperated, but as an entity existing only in this ‘drawing back’, that is, in its ‘retreat’. ‘The political’, in their account, is to be elaborated in the very condition of its ‘exhaustion’. As such, the key distinction is not between the polis and the oikos, but between different approaches or orientations towards the retreat of the polis. For Nancy, entities such as the ‘community’ and ‘capital’ are essentialisations of the very conditions of this loss of meaning, namely that being is respectively relational and ‘reticulated’ (2000:73- 3 Indeed Nancy later cites Arendt as being among a small coterie of individuals responding to the forms of questions he seeks to set out (1991:156 n.2). 74).4 In short the withdrawal of political meaning gives way to borrowed figures, whose authority, meaning or influence we barely understand. The force and productivity of the ‘governmentality’ approaches presented above was in their critical demonstration of the play of these borrowed figures that seek to plug this loss of meaning. As a major step beyond that tradition however, Nancy enjoins us to engage with the loss of meaning on the very conditions of its retreat, and it is in this sense that Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy speak of a re-treating of the political. As noted, with Arendt, Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy claim that ‘political’ dialogue is finished. What they argue is shown by such an admission is the fact that ‘the political’ must be re-engaged in discussion attentive to this being-already-finished. Nancy will describe, throughout his work, the condition of politics as ‘finitude’; as a being already-in-retreat. Again this is an approach deeply indebted to Heidegger. As the latter displayed in his ‘destructive’ approach to metaphysics, to practice philosophy will henceforth mean only to think at the end of philosophy, which means to ceaselessly (for such a thought cannot lead anywhere, but only begin again) re-engage and re-consider the completion of philosophy. What Nancy achieves is a transposition of this thought of completion to the socio-political question of community; to think as community as the completion or exhaustion of community, of which more later. What is to be done? 4 Nancy’s idiosyncratic approach to Castells’ (2000) analytic of the ‘network society’ is to posit in the emergence of networked life an exposure to the originary reticulation of being (see Armstrong, 2009). But what form, critics of Nancy’s work ask (see for example Fraser, 1984), would this ‘thought’ take? For there appear to be only negative delimitations: the retreat designates a refusal of the injunction to submit to economic necessity, to the intrinsic reality and danger of anti-social behaviour, to the organic truth of community as a positive force, and so on. In pursuing a ‘finite’ politics, one is refusing, as Lacoue-Labarthe states, that “intimidation which, because it is ‘regarded as sacred’, is exercised today by the political and which forces anyone whatsoever ... to be accountable, to show their hand, to intervene, to commit themselves” (1997:97). For Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy’s work pursues Heidegger’s recognition of theory as the “supreme realisation [Verwicklichung] of genuine practice” (cited in Sparks, 1997:64). “What is to be done”, Nancy (1997) argues, cannot be considered a separate problematic from theoretical determinations of what the world is and what hopes one may hold for its transformation. A positive, practical determination is as such precluded, as by necessity a politics proper to the thought of the retreat must only be the retreat itself; investigating and pursuing the withdrawal of political figures. This may nonetheless be proposed as a foregrounding of the question, or moreover a holding open of the question of the political. Such a proposal is not to be confused with critique (and it is here that the distinction with ‘governmentality’ becomes further apparent); it implies rather the inscription of figures as originarily uncertain. As Nancy notes; What will become of our world is something we cannot know, and we can no longer believe in being able to predict or command it. But we can act in such a way that this world is a world able to open itself up to its own uncertainty as such. (1997:158) In other words, we might seek to pursue this thought of the retreat; to inscribe a thought of withdrawal as the originary uncertainty of political figures. And we might also seek to oppose those politics that would, in a move described presently, obscure or neutralise this withdrawal in a ‘will-to-figure’ or ‘will-to-immanence’. Christopher Fynsk thus describes, referring to the primary terrain of this practice that will be addressed in this article, that of community and its withdrawal in the dispersal of communication, these two aspects of ‘what is to be done’; one can attempt to favour such communication, and one can attempt to engage in a critique of the ideologies that dissimulate what Nancy calls the absence of community (or of the fact of the impossibility of communion or immanence as it appears to us today, after the closure of metaphysics). (1991:xi) Thus in the next section we turn to this community, in its absence, exhaustion, withdrawal or retreat, and to the authority it fails to possess. Section 2: Authority That the community would fail to possess authority would be anathema to the ‘communitarian’ adherents of a ‘politics of lost authority’. For it would be, in these accounts, the defining feature of a strong, resilient community that it is able to regulate the behaviour of its members in a manner that they recognise as legitimate. Inasmuch as the criminal law is itself recognised in such a way, it is because it has been fully internalised by the community as its own moral code (Etzioni, 1995:22). Such an analysis echoes Max Weber’s (1978:212-5) definition of authority as pertaining to those relationships in which the power held by one party, manifested in the likelihood of their orders or commands being followed, is legitimated by those following or subordinated by these acts. Yet Weber’s primary interest, among the three ideal types of authority he discerned,5 in the charismatic (Riesebrodt, 1999), that is, in the accumulation of authority through heroic or creative acts, highlights an aspect of authority that contradicts this communitarian account. For in the charismatic, authority is drawn not from the togetherness of its members and their achievement of a unified consensus, but on the contrary, from the channelling of an excess. Such an account raises the problematic of authority that will be pursued in this article; of the holding together of community through the interiorisation of an outside to the discernible social order. It is, again, to Arendt that we must turn in explicating this paradoxical assertion. An outside, inside Much as The Human Condition demonstrated the extent to which we cannot think the political, Arendt’s earlier essay “What is authority” (1954) addressed our misunderstanding of authority. The essay describes the form of authority that “came to an end” (8) as modernity successfully challenged, and dissolved, every form of authority pertaining to a transcendent relationship of exteriority. Arendt states that it is principally Roman authority whose absence haunts us; an authority derived, in a manner specific to the mythology of the city of Rome, from the “sacredness of foundation” (17). 5 Namely ‘legal-rational’, ‘traditional’ and ‘charismatic’. An authoritative act was one that was connected with, and as such augmented (the original meaning of authority is derived from augere, to augment) the transcendent event of the founding of Rome (18). Arendt is clear that the Roman model of augmentation and testimony, and of a ‘sacred’ source of authority, has definitively disappeared from our thought. To live without the understanding that the source of authority ‘transcends power’, is to live in a terrain denuded of political action, and to be faced with the elementary problems of human co-existance (29). Totalitarianism, Arendt argues, which dispenses with the pyramid-like authoritarian structure in favour of a network of power-relations operating around an empty space (5), thrives upon such a terrain in which the authority of government is no longer recognised (1). Returning to Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy’s above cited recognition of this “loss of authority as a distinct element of power” (1997b: 129), if ‘totalitarianism’ denotes the removal of any alternative frame of reference (1997a: 111), it is totalitarianism under a ‘new’ or ‘soft’ form, they note, that would denote the situation in which the exhaustion of political authority has produced the total domination of ‘social’ concerns (1997b:1289). Combining this language of authority and power with the above description of the political, the saturation of the political by the oikos may be seen to correspond to the uninterrupted play of power; to the closure of an authority that might contest or disrupt the play of techniques and strategies described by the ‘governmentality’ approach. Yet from their perspective such an authority is not historically ‘past’, but rather in its withdrawal is permanently at stake. It was noted above that a significant blind-spot in the governmentality accounts is the specificity of authority as a form of power. What this means, from this Arendtian perspective continued by Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy, is that it continues the failure to ask the following question; what does it mean to have lost authority? For while the governmentality perspective draws out in a very productive fashion the forms of power that fill this denuded space, it does not ask of how our response to this loss conditions not only the shape of government, but also the potential for political action. In short, the foregrounding of this question leads to two observations. First, that the manner in which the communitarian accounts specifically targeted by Rose as setting out the contours of ‘ethico-power’ might themselves be specific responses to this loss.6 And second, that a holding open of this question, as the deconstructive exposure to contingency described above, might itself be the site for contesting this domination of social concerns. For in turning to the ascription to community, in the later text The Inoperative Community (1991), of “the sovereignty of its sharing” (26) what we may draw from Nancy, in contrast to the end of authority in Arendt’s account, is a political possibility highlighted by this loss.7 Sovereign figures 6 This observation would similarly re-frame the startling regularity of ‘golden age’ community accounts (see Pearson, 1984). 7 This is a possibility Arendt herself recognises in a later text on the American Declaration of Independence (Arendt, 1977). Again, Nancy seeks to work through the implications of Arendt’s elucidation of Roman and Christian authority, paying particular attention to the manner in which the ‘sacredness of foundation’ is positioned by Arendt as existing only, for us ‘moderns’ at least, in a state of withdrawal. And again, Nancy will take this proposition a step further. Turning the focus to the crisis of this latter term, Nancy follows Arendt in observing the impossibility of a transcendent authority around which subjects could achieve a common union. Yet, if the figure of the sovereign presented itself as a ‘connection’, through the practices of testimony, to transcendence, and it is precisely this sovereign figure of transcendent alterity that is in retreat, again for Nancy it is this existence as retreat that must be fully engaged with. It is, again, in the retreat of the sovereign figure that we will find a thinking, and practice, of authority proper to the ‘inoperative community’, as Nancy seeks, in his later work, to re-inscribe the term. It is in this focus upon the loss of sovereign authority, as represented in the absent figure, that Nancy’s work enters into a strange coalition with the ‘politics of lost authority’. For in the focus upon a golden age, what the ‘communitarian’ authors testify to, in Nancy’s view, is the existence of community as loss. To display what it is that differentiates Nancy’s work from this tradition, it is necessary to detail the dual role of the ‘figure’ in Nancy’s thought, as it gives an indication as to how this re-working of sovereign authority is achieved in his work. Nancy often introduces texts by defining a certain withdrawal of figures, whether in the closure of “(Western) philosophy’s political programmes” (1991:xxxviii) or in a lack, or loss, of ‘meaning’ (2000:1). Indeed, in the retreat of political and religious authority, Nancy observes the withdrawal of “every space, form, or screen into which or onto which a figure of community could be projected” (2000:47). At the same time however, Nancy clearly adopts a critical stance with regard figures of community as they are ‘at work’ in political discourse, a position encapsulated in the rhetorical question; “does meaning not become ‘totalitarian’ as soon as it takes figure [prend figure]” (Nancy, cited in Sparks, 1997:xxv). It is as such important to stress the distinction, alluded to above, between the immanent ‘figure’ and the ‘transcendent’ withdrawal of the figure. In the former case ‘immanence’ denotes a similarity, and simultaneity, of something to itself; the immanent figure is the concept that forms its own ground, that provides its own cause, that gives its own ‘essence’, that gathers its meaning within itself. In the case of community, Nancy’s work has frequently returned to the immanent figure proper to a ‘golden age’, a figure for which; always it is a matter of a lost age in which community was woven of tight, harmonious, and infrangible bonds and in which above all it played back to itself, through its institutions, its rituals, and its symbols, the representation, indeed the living offering, of its own immanent unity, intimacy, and autonomy. (Nancy, 1991:9) Enclosed, stable and unchanging, the immanent figure of community, as it is deployed in the ‘communitarian’ literature, turns the originary relationality of the community, of which more below, to an essence; a non-relational, unified community figure. Yet the fact that this community can only ever be ‘lost’, in the communitarian literature as elsewhere, is instructive. For “[c]ommunity has not taken place” (Nancy, 1991:11); or rather, it has only taken place as this constitutive loss, as a retreat of immanent figures. What the writing of Etzioni and others demonstrate is that the immanent figure, as it immediately withdraws, betrays a transcendence at the heart of any thinking of the figure. Nancy is critical not of the figure as such, but rather a “will to absolute immanence” (1991:12), doubling as Sparks notes as a “will-to-figure” (1997:xxiii), which reacts to the withdrawal of figures by seeking to strengthen and solidify them or to find in their absence a further reason to clarify and reiterate their importance. Alasdair MacIntyre (1997) is indicative of this position, his work re-stating a need for figures, it being only through a relation to a certain model of justice, practised and embodied within a community setting, that the subject may acquire and practice a moral subjectivity. Such a community, Nancy notes, could never actually ‘come about’ as such; indeed in its immanent ‘union’ it would only present the death of community (1991:12), if that is we re-think community, as Nancy states we must, as an originary relationality. In short, the community figure, Nancy states, is lost. Yet as loss, this same figure exposes us to a transcendence; an exteriority experienced as the impossibility of community. Its ‘presence’ is only the absence of any screen upon which a present community could be projected. Thus, in the same manner as Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy (1997b) rejected the historical schema they took to be implicit in Arendt’s account of the saturation of the political (131), Nancy argues that the sovereign figure, as presented in Arendt’s ‘sacredness of foundation’, is not an ‘anterior’ space, whether ontological or historical, but rather present only in its withdrawal. Nancy returns, regularly, to Bataille’s assertion that “sovereignty is NOTHING” (cited in Nancy, 2000:139). Were we somehow to peel back the historical layers, we would find only the non-figure of sovereign alterity, which would be ‘present’ to us only in its withdrawal from presence. Thus, while for Bataille, in the last instance sovereignty reveals itself to be an ‘empty’ place, for Nancy this empty place is only the space, or moreover the spacing, of a ‘retreat’. To ask of sovereign authority, the specific form of authority observed by Arendt in its absence, is for Nancy to ask of an authority specific to this retreat; an authority that arrives not from an ‘outside’ but in the very retreat of this outside. It is an authority present as the absencing of sovereign alterity, as the retreating movement shown to us by the ‘crisis’ of political authority, and directly opposed to the efforts to form stable and immanent forms of political authority to answer this crisis. The key to understanding this re-thinking of the authority of community, in which authority is the community itself in its originary being-in-common, is the focus Nancy places on this latter modality of being in a re-working of Heidegger’s concept of mitsein. “[T]he sovereignty of its sharing”, the line from The Inoperative Community from which I have taken the title of this article, implies the thinking of a sovereignty, and an authority, of plurality. It is the continuation, as an alternative language of authority, of the very originary condition of ‘men’ proposed by Arendt, but which from Nancy’s point of view her thought does not fully explore as itself the withdrawal or retreat of immanent figures. Section 3: The inoperative community For lack of a better term, it is community that, despite its use as an ‘immanent’ figure, denotes the space in which the retreat of sovereign authority takes place; it is the space of the between, the relation, the with. Nancy opens his 1986 text The Inoperative Community (1991) by stating the most urgent question for modernity to be “the dissolution, the dislocation, or the conflagration of community” (1). All figures for political community (nation and class being the most prominent), are, he notes, in fragmentation. Given this crisis of community, the text takes up, again, the thought of the retreat; against the ‘will-to-figure’, and its production of immanent community forms, community must be thought as fragmentation. Such a thought of community continues the critical assessment, detailed above through the rubric of contemporary ‘governmentality’ studies, of the manner in which the immanent figure of community allows a certain authority to gather around particular groups and subjects. A failure to engage with the crisis of political authority and the retreat of sovereign alterity is manifest in a terrain of ‘immanent’ authorities that elude contestation, for which we have little analytic tools or critical purchase to question, deconstruct or subvert. Yet Nancy attempts to explore this critical project not through critique as such, but rather by attempting to re-inscribe the very meaning of community (Fynsk, 1991:ix). If traditional concepts of community, relying upon such immanent figures, deconstruct community only to re-construct it under a different figure (intersubjectivity, care, human rights, and so on) Nancy finds in Bataille an entirely different experience of community; The crucial point of this experience was the exigency, reversing all nostalgia and all communal metaphysics, of a “clear consciousness” of separation – this is to say of a “clear consciousness” ... of the fact that immanence or intimacy cannot, nor are they ever to be, regained. (1991:19) Fully engaging with the impossibility of regaining community means re-thinking the experience of community as a pure ‘separation’, which is to say the relation in its most original form. If the focus on ‘dissolution, dislocation or conflagration’ continues the ontological schema from “The retreat of the political” (Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy, 1997b), through this particular focus upon the fragmentation of the ‘unified’ community as a question of plurality, the text seeks to open a new set of questions pertaining to the relation. Withdrawal takes the form of ‘communication’ and ‘contagion’; trangressions of the limit between beings. For what community displays about being, Nancy asserts, is that it must be a question of the with. If Heideggerian dasein denoted finitude as the limit between the self and its absence in death (as being-towards-death), of equal, if not more, importance to Nancy (and he is as such critical of Heidegger’s relegation of mitsein to mit-dasein (2000:93)) is the limit between the self and the other. Being is already being-with, and the retreat of the self-similar, stable community figure is the retreat as the emergence of being-with. Immanent community figures Yet as noted above, the will-to-figure is the will to essentialise the with. It is a will that manifests itself in the two immanent figures to which our thinking of community is bound; of community as communion and community as work. The former designates the intimacy of the community to itself in an ‘essence’ or ‘meaning’, and as such denotes a critical perspective upon any tendency to imagine the community as a unity of component subjects. Thus where Nancy’s work is most formulaically interpreted, it is as an anti-communitarianism; an opposition to any replacement of the atomistic subject in favour of a similarly reified community subject (Norris, 2000:273). For Nancy follows Bataille in recognising that such a concept, with its inherent nostalgia, is a longing for death, as the closure of community in its contingency. This tension between communion and contingency, Nancy recognises, is the very shift between the transcendent relationship with the outside and the withdrawal of this outside. Thus following Arendt Nancy argues that ‘if there are no more gods’, by which we may read the presence of a transcendent alterity, ‘there is no more community’, as the community looks to itself, to its immanent communion around an essence or destiny. Yet, in contrast again to the presupposition that the task of political philosophy is to set out a desirable state of affairs in order to reconstruct it in the present, Nancy firmly rejects the question of returning the community to its ‘face to face’ relationship with the gods (that is, to the transcendent outside); “the less so in that it is with the withdrawal of the gods that community came into being” (1991:134). The second figure, that of community as work, denotes those instances in which the term is put to the service of achieving certain goals. The exemplary articulation of this figure, Nancy argues, is to be found in Marx, who in developing an admirably critical perspective towards religious communion and its political role, nonetheless envisaged its replacement by a no less ‘immanent’ community figure; the true spirit and heart, the spirit and heart of the true human community at work in the production of man himself, were to substitute their immanent authenticity for the false transcendences of the political spirit and the religious heart. (2007:7) In short, the Scylla of community as a unity of members is joined by its Charybdis; the posing of community as an operative project. Returning to the ‘politics of lost authority’, the reliance upon these two figures is immediately apparent. Community is at once figured as a pre-existing togetherness of individuals (whose absence demands its reclamation) and as the project of authoritative self-regulation they are expected to complete. The product of these politics, as Rose notes, are newly configured circuits of exclusion and inclusion operating through the everyday moral obligations to the self and to others (188). Rose notes further the importance, within these circuits, of the production of an authority, located in ‘the community’, proper to this power (1999:187). Such an authority has become manifest in the significant changes to the law implemented through the ‘Community Safety’ agenda that have presented significant challenges to the model of the central authority of the criminal law. If these two figures for immanent community are in themselves impossible (it is indicative that community is always mobilised in political terms as something that is absent, either a dimly visualised golden age or an area of the population that current strategies are failing to engage), Nancy’s opposition is, as noted above, not the figures themselves, but to the will-to-immanence implicit in communitarian attempts to remake them in the present. This position stands in opposition to the tendency that dominates critical perspectives on the politics of community; that the alternative to the exclusion of individuals through community involvement programmes would be the proposition of a model for community in which all can be included in its realm. Nancy’s response, in contrast, is to pose the alternative to the circuits of inclusion and exclusion identified by Rose and others to be the inscription of community as an ‘intimate exteriority’ (Levett, 2005:430); the exteriority of the retreat, now posed as the community itself in its originary plurality, as the ‘intimate’ condition of our common existence. Interruption For in Nancy’s opposition to both communion and work, resting upon this ‘inoperative’ understanding of community, the common is itself a de-stabilisation of the immanent figure; an originary uncertainty that opens the figure to its own contingency. The inoperative community is ‘present’ only as ‘interruption’: the disruption of immanent figures of community. It is an unworking, and any attempt to put it to work, whether Marxist attempts to set the community to realising man, or communitarian attempts to realise authority, is to neutralise this appearance of community as being-in-common. This experience of community implies, in the context of authority, a re-thinking of the relationship between community and authority in terms of a different thought of sovereignty; not the sovereignty of the figure but the sovereignty of this plurality. For on Nancy’s account “only a discourse of community, exhausting itself, can indicate to the community the sovereignty of its sharing” (1991:26). If the community is ‘sovereign’ through the ‘intimate exteriority’ that is its interruptive presence, through its very exhaustion as a figure, an authority of the community proper to this sovereignty would not be an authority to compel in Weber’s sense, but an authority of being; the authority that being-with is. Bonnie Honig (1991:98) uses the term ‘weightiness’ to denote Arendt’s description of authority, in Roman antiquity, as the ability to carry the connection to the foundational event and all prior augmentations to it. In this authority that being is, Nancy is describing the ‘weightiness’ of our shared, but different, existences. In Nancy’s schema, by thinking the withdrawal or exhaustion of the community ‘figure’, and the absence of a sovereign authority as embodied in a communion of community, what emerges is a distinction between the authority possessed by a community and the authority the community is. If the former corresponds to an exercise of power located in the community as the ‘true’ representatives of a location, identity or morality, the latter is an authority, or weightiness that, as the altogether mundane event of our being-incommon, is the no less radically political moment in which being appears in its plurality. Hypostatisation In contrast we may observe how Community Safety interventions hypostatise – render material or immanent – this disruption of the formal structure. Again this observation begins with the role of community in the ‘communitarian’ accounts, whose focus upon the formation of the moral self within the community setting turned the contingency of affective experience, in other words the very excessive condition of the loss of meaning, to an observable and manipulable event to be shaped and channelled within a system of governmental power. The background to this hypostatisation was the socio-historical claim that, as such a moment must be formed in the ‘community’ conceived as a communion of members, the apparent decline of the moral self must imply a decline of community as the site of this moral formation. The need to tighten up the authority of the community as such took the form of the political initiatives described above in which the demand made of the criminal law was for it to better represent the community as this immanent hypostatisation. It is in a manner somewhat foreign to Nancy’s work that I have used ‘authority’ in this article to describe the contestation of this hypostatisation. Nonetheless, as the ‘politics of lost authority’ becomes increasingly dominant, I argue that it is in the holding open of the loss of authority that the plurality of being that gives us in our differences, the very plurality that allows us to be regulated, to follow, to trust and guide each other, might be re-inscribed in the denuded terrain of immanent authorities. Concluding Thoughts Having set out to examine in this article the concepts of community and authority through the work of Jean-Luc Nancy, it is clear that we have also been following a reexamination of the political imperatives of the latter’s thought through recent developments in the politics of community. In referring to the ‘loss of authority as a distinct element of power’ (Lacoue-Labarthe and Nancy, 1997b:129), authority is examined by Nancy in its encroaching absence, in other words as part of a general political agenda to expose terrains of exhaustion in their retreat. The dominance of the oikos or of socio-technical options is the dominance of power without the community that might question, disrupt or contest this power. Thus the urgent problem facing our community-saturated times, as I have set it out, is a ‘politics of lost authority’ developed through the Community Safety paradigm in which political contestation is gradually foreclosed. ‘What is to be done’ is to oppose this closure, for which in this article I have used the term ‘immanent authority’, to oppose it as the community. This article has sought to draw these situated contestations into a politics of the common; an articulation of the impossibility of immanent comm-union in whose name our engagements of the social must be drawn. As authority itself becomes the terrain of the closure of community we find an imperative to develop another language of community and its authority. In short, it demands a research agenda focusing not on exclusion,8 but upon the destructive inclusion of individuals as immanent figures, and the manner in which practices of community and of politics may pursue the continual interruption of this inclusion. A turn to community, and the ‘sovereignty of its sharing’, in this context, is the affirmation that community has no authority to shape the behaviour of its members. Community ‘has’ only its own closure in a ‘will-to-immanence’ and the arrangement of power-relations proper to this movement, what I have termed in this article a ‘politics of lost authority’. What Nancy’s thought demands, or moreover what community in its retreat demands, is a thought and a practice of this failure; a recognition that community 8 This tendency, for which there has not been the space to explore in this article, is taken by many (see Turner, 2007; Krasmann, 2007) who seek to continue Agamben’s (1998) thesis on the ‘state of exception’. as this guarantee is exhausted, completed, finished. Instead of seeking to plug this failure with a return to the figure, we must repeat that the authority of community is the interruption of this claim; it is the weightiness of being, in its plurality, that arrives in the very retreat of what community cannot be. Bibliography Arendt, H. (1968). What is authority? [online]. University of Texas. Available from: https://webspace.utexas.edu/hcleaver/www/330T/350kPEEArendtWhatIsAuthorityTabl e.pdf [accessed 06/06/2011]. Arendt, H. (1977). Between Past and Future. New York: Penguin Arendt, H. (1998 [1958]). The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago. Bauman, Z. (2004). "Community safety and social exclusion." In Squires, P. (Ed.), Community Safety: Critical Perspectives on Policy and Practice. Bristol: Policy. Blond, P. (2009a) Rise of the Red Tories [online]. Prospect, 155. Available from: http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/2009/02/riseoftheredtories/ [Accessed 06/11/2010]. Brokenshire, J. (2011). Anti-Social Behaviour: New proposals. The Home Office. Available from: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/media-centre/videotranscripts/asb-proposals/ [accessed 08/06/2011]. Cameron, D. (2009). Speech: The Big Society [online]. The Conservative Party. Available from http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2009/11/David_Cameron_The_Big_Soc iety.aspx [accessed 22/06/2011] Castells, M. (2000). The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell Dean, M. (1999). Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. London: Sage. Elster, J “The market and the forum: three varieties of political theory” in Bohman, J. and Rehg, W (eds.) Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics. Boston: MIT Press. Etzioni, A. (1995). “The responsive communitarian platform: rights and responsibilities” in Etzioni, A. (ed.) Rights and the Common Good: The Communitarian Perspective. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Etzioni, A. (1998). The New Golden Rule: Community and Morality in a Democratic Society. New York: Basic Books. Foucault, M. (1991) “Governmentality” in Burchell, G. and Gordon, C. (eds.) The Foucault Effect. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf Fraser, N. (1984). "The French Derrideans: politicizing deconstruction or deconstructing the political?" New German Critique, 33: 127-154. Fynsk, C. (1991). "Foreword: experiences of finitude." In Connor, P. (Ed.), The Inoperative Community. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Great Britain (1998) The Crime and Disorder Act. London: HMSO Hale, S. (2005) Blair's Community: Communitarian Thought and New Labour Manchester: Manchester University Press Honig, B. (1991). "Declarations of Independence: Arendt and Derrida on the problem of founding a republic." The American Political Science Review, 85(1): 97-113. Krasmann, S. (2007). "The enemy on the border." Punishment & Society, 9(3): 301-318. Lacoue-Labarthe, P. (1997). “Political seminar: contribution II” in Sparks, S. (ed.) Retreating the Political. London: Routledge Lacoue-Labarthe, P. and Nancy, J-L. (1997a) “Opening address to the Centre for Philosophical Research on the Political” in Sparks, S. (ed.) Retreating the Political. London: Routledge Lacoue-Labarthe, P. and Nancy, J-L. (1997b) “The 'retreat' of the political” in Sparks, S. (ed.) Retreating the Political. London: Routledge Levett, N. (2005). "Taking exception to community (between Jean-Luc Nancy and Carl Schmitt)." Journal for Cultural Research, 9(4): 421-435. MacIntyre, A. (2007[1981]). After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. London: Duckworth. May, T. (2010). Moving Beyond the ASBO: Speech at Coin Street Community Centre [online]. The Home Office. Available from: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/mediacentre/speeches/beyond-the-asbo [Accessed 09/06/2011]. Nancy, J-L. (1991). “The Inoperative Community.” In Connor, P. (Ed.), The Inoperative Community. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Nancy, J-L. (1993). "Lapsus judicii." in Sparks, S. (ed.) A Finite Thinking; Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford: Stanford University Press Nancy, J-L. (1997) “What is to be done” in Sparks, S. (ed.) Retreating the Political. London: Routledge Nancy, J-L. (2000). Being Singular Plural. Stanford: Stanford University Press Nancy, J-L. (2007). "Church, State, Resistance." Journal of Law and Society, 34(1): 313. Norris, A. (2000). "Jean-Luc Nancy and the myth of the common." Constellations, 7(2): 272-295. Pearson, G. (1983). Hooligan: A History of Respectable Fears. London: Macmillan. Reiner, R. (2007). Law and order: An Honest Citizen's Guide to Crime and Control. Cambridge: Polity. Rose, N. (1999). Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Straw, J. (1997). "Speech to the House of Commons: Policing of London (14th November)." Parliamentary Debates, Commons Fifth Series (Vol.300): Col.1145. Turner, B. S. (2007). "The enclave society: towards a sociology of immobility." European Journal of Social Theory, 10(2): 287. Villa, D. (1992). "Beyond good and evil: Arendt, Nietzsche, and the aestheticization of political action." Political Theory, 20(2): 274-308. Weber, M. (1978[1922]). Economy and Society; An Outline of Interpretative Sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press.