Mapping Of The Civil Society

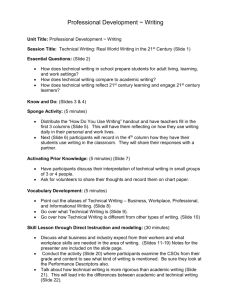

advertisement