The social shaping of population health

advertisement

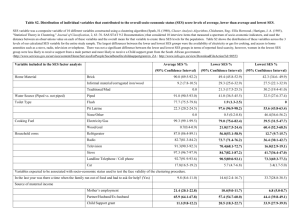

The Social Shaping of Health Disparities: The Fundamental Cause Hypothesis Bruce Link Heron April 7, 2011 U.S. All Cause Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 by Race – 2005 1200 1000 1016.5 785.3 800 600 white black 400 200 0 National Center for Health Statistics – Health United States 2008 U.S. All Cause Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 People Ages 2564 by Education -- 2005 900 821 800 700 600 606 472 500 400 < 12 years 12 years 13+ years 352 300 249 165 200 100 0 Males Females National Center for Health Statistics – Health United States 2008 U.S. Percent Fair or Poor SelfReported Health by Poverty Level and Race/Ethnicity 30 26 25 20 21 21 20 17 15 14 15 14 10 10 5 6 6 Overall White 9 Below 100% 100%-less than 200% 200% or more 0 Black Hispanic ional Center for Health Statistics – Health United States 2006 – From NHANES Surveys Age Standardized Mortality Rates by SES Classification (NS-SEC) in the North East and South West, Men 25-64, 2001-2003 Hi Manager Prof. 700 700 600 Lo Manager Prof. 500 Intermediate 400 400 Small Employers 300 200 210 195 100 0 North East South West Lower supervisory and technical Semi-Routine Routine NS-SEC= National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification What Are the Mechanisms that Account for the Association? ? SES, Race Mechanisms Smoking, Diet, Exercise, Stress, Etc, etc. ? Mortality Morbidity Deaths Per 1000 Among Taxpayers and Non-Taxpayers in Rhode Island 1865 Age Categories (examples) Taxpayers Non-Taxpayers 93.4 189.8 30-39 4.5 15.5 60-69 15.1 39.5 Under 1 Chapin AJPH 1924 Deaths per 1000 (age adjusted) by SES of Census Tract -- Chicago 1930 SES Males Females 1--Lowest 15.1 12.3 2 11.6 10.2 3 10.2 9.0 4 9.2 7.9 5--Highest 8.7 6.8 Coombs, Medical Care, 1941 What is the point? • Imagine yourself back in Rhode island in 1865 and doing what we just did for the current data – we might have asked what were the mechanisms involved? • Contaminated water, poor sanitation, crowded substandard housing – the diseases were cholera, TB, small pox… • We did something about the risk factors, we developed vaccines, and people don’t die of TB, small pox and cholera in Rhode Island any more. • But the SES association is resilient. The Concept of Fundamental Social Causes Fundamental social causes involve resources such as knowledge, money, power, prestige and beneficial social connections that determine the extent to which people are able to avoid risks and adopt protective strategies so as to reduce morbidity and mortality. Because such resources can be used in different ways in different situations, fundamental causes have effects on disease even when the profile of risk and protective factors and diseases changes radically. It is their persistent effect on health in the face of dramatic changes in mechanisms that leads us to call them “fundamental.” How Social and Economic Resources Affect Health – The Importance of Contexts • Resources operate at the individual level – people use their knowledge, money, power, prestige and beneficial social connections to obtain healthy outcomes. • But resources also provide access to generally salutary contexts – neighborhoods, occupational conditions, marriages – access to health consequential circumstances comes with access to contexts in a sort of “package deal.” US Life Expectancy at Birth 19002000 80 77 75 74 70 70 65 61 60 55 55 50 45 47 40 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 US: Heart Disease -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 People 640 587 540 559 493 440 412 340 321 293 240 258 140 40 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 1995 2000 Cancer (green) and Stroke (Yellow) -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 People 240 220 200 180 194 181 194 178 199 208 216 210 200 186 160 148 140 120 100 96 80 65 60 63 61 40 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 1995 2000 50 2004 National Center for Health Statistics – Health United States 2006 US : Flu (blue) and HIV (green) -- Ageadjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 People 60 50 54 48 42 40 37 33 31 30 24 20 16 10 10 5 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 1995 2000 Percentage Self Reporting Health as Excellent or Good by Age Group (40-49 yellow and 60-69 blue) and Decade of Birth using 1972 to 2004 General Social Surveys 90.00% Age 40-49 80.00% 74% 82% 82% 84% 76% 74% 70.00% 63% 60.00% 50.00% Age 60-69 57.00% 52% 1900's 1910's 1920's 1930's 1940's 1950's 1960's Adapted from: Robert Warren and Elaine Hernandez (In Press) Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Table 2 Something is Driving these Dramatic Improvements in Health X ? Shouldn’t whatever “x” is be an important part of our explanations of health disparities? Do Key Explanatory Variables in Theories of Disparities Account for Trends Toward Improvement in Health Over Time? • How about genetic factors? • Social involvement and participation? • How about income inequality? • Relative position on hierarchies? Of course, X is not any one thing but many things • The discovery of the germ theory is a strong candidate for declines in rates of infectious diseases in the first half of the 20th century. • Recent declines in age adjusted rates of death from lung cancer are probably influenced by the lagged effects of declines in smoking rates in earlier decades. • The rapid decline in HIV/AIDS mortality is probably related to the new anti-retroviral drugs that were developed and disseminated in the late 1990’s • And then screening for disease, public health efforts to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables, promote exercise, eradicate smoking, and smog control, flu shots, seat belts, angioplasty, screening for early detection of cancer, etc. etc. • So X is clearly not just one thing and is likely different things for different diseases…and probably different things at different times….But the confluence of all of these things has clearly had an enormously positive impact on population health. • Clearly human beings have dramatically increased their capacity to control disease and death. Fundamental Cause Reasoning Concerning the Sources of Disparities: The Core Proposition • Our enormous capacity to control disease and death combined with social and economic inequality creates health disparities. • It does so because of a very basic principle – When we develop the ability to control disease and death, the benefits of this new found capacity are not distributed equally throughout the population, but are instead harnessed more securely by individuals and groups who are less likely to be exposed to discrimination and who have more knowledge, money, power, prestige and beneficial social connections. • People who are more advantaged with respect to resources such as these and who are less likely to be held back by discrimination benefit more and have lower death rates as a consequence. Disparities are the result. Explanations for Race and SES Disparities that Have Different Emphases than a Social Shaping Fundamental Cause Approach • • • • • Genetic Differences Health Selection Relative Deprivation Job Control Stress of Lower Position Test #1 -SES Associations with More and Less Preventable Causes of Death • We say that SES differences arise because people of higher SES use flexible resources to avoid risks and adopt protective strategies • it follows that the SES gradient should be more pronounced for diseases that we can do something about… for which there are known and modifiable risk and protective factors… • Our first test involves ratings of the preventability of death from specific causes US National Longitudinal Mortality Survey • Very large study of a nationwide sample of over 350,000 people. • Interviewed as part of the US Current Population Survey (assesses unemployment etc.) and followed for 9 years with National Death Index for mortality and cause of death Relative Risks of Death by Income -- National Longitudinal Mortality Study Income (1980 $) Women 45-64 Men 45-64 < 5000 2.32 3.13 5000-9999 1.79 2.63 10000-14999 1.56 2.03 15000-19999 1.35 1.69 20000-24999 1.21 1.47 25000-49999 1.09 1.28 50000+ (reference category) 1.00 1.00 Sorlie et al. AJPH 1995 The Rating Task • Thinking of both our ability to prevent a disease from occurring and to treat it once it occurs, to what degree was it possible, in the early 1990’s to prevent death from this disease? • Rated on a 5 point scale from “virtually impossible to prevent death” to “virtually all deaths preventable” • Inter-rater reliability .85. Correlation with Rutstein independent ratings .57. Examples of Hi and Lo Preventability Diseases • Low Preventability: brain cancer, ovarian cancer, gallbladder cancer, multiple sclerosis, pancreatic cancer, • High Preventability: lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, colon cancer, pneumonia National Longitudinal Mortality Study Percent Dying During 9 Year Follow-Up: Men and Women 45-64 9 8.2 8 7 6 5 4 5 16+ Years 12 -15 years < 12 Years 4.1 3 1.8 2 1.8 2.1 1 0 Hi Preventability Lo Preventability Phelan, Link, Diez-Roux, Kawachi and Levin. 2004 JHSB Test # 2 Evidence Bearing on the Hypothesis Trends Over Time • If the core proposition is true we should find that disparities by SES and race emerge when new health enhancing information or technology is obtained: – E.g. Heart disease, Hodgkins Disease, Colon Cancer • If death from a disease remains unpreventable – disparities will not change dramatically with time – E.G. Brian cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Pancreatic Cancer Trends by County-Level SES and Race in the US Brain Cancer -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1950-1999 (Males) US 6 White Males4.97 5 4 3 2 3.86 4.18 4.5 5.17 4.81 3.21 2.84 5.04 2.91 5.26 3.1 5.47 3.08 Black Males 1 0 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95-99 Ovarian Cancer -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1950-1999 (Females) US 10 9 8 7 6 5 White Females 9.03 8.35 8.91 8.9 8.88 7.21 8.58 6.66 8.11 8.08 8.13 6.56 6.43 6.72 Black Females 4 3 2 1 0 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95-99 Pancreatic Cancer -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1981-2002 US 14 12 Black 12.3 11 11.7 12.3 12.1 11.5 11.3 11 8 8.2 8.2 10 8 8.4 8.3 White 8.2 8.2 8.2 6 4 2 0 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 1996 1999 2002 Heart Disease -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1950-2000 US 600 586.7 584.8 559 548.3 550 512 492.2 500 450 455.3 400 409.4 Black 391.5 350 White 300 317 324.8 253.4 250 200 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Breast Cancer-- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1950-2000 45 40 Black38.1 35 30 25 32.4 32 27.9 32.5 28.9 32.1 31.7 33.2 34.5 White 26.3 25.3 32.2 23.9 20 15 10 5 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2004 Colon, Rectum and Anus -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1960-2000 US 34 32 30.9 30.6 30 29.2 28.3 27.4 28 28.2 26.1 26 White 24 22 Black 24.1 22.8 20.3 20 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted pancreatic cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 or more years, 1968-2005 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted pancreatic cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 or more years, 1968-2005 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted lung cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 or more years, 1968-2005 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted lung cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 or more years, 1968-2005 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted lung cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 years and over by county SES percentile, 19682005 What do These Tests Tell Us? • This is consistent with the social shaping perspective and it says that the scope of problem is large… BUT • The link to new knowledge and technology is not as direct we would like. Let me turn now to three stories where the linking is somewhat better…. Income Disparities in Cholesterol • Chang and Lauderdale use data on cholesterol levels from NHANES before (1976-1980) and after the introduction of highly effective statins (1999 -2004) • Income is assessed as the poverty income ratio Income Gradients for Total Cholesterol 1976-80 and 1999-2004: Predicted Lipid Levels from NHANES for Women 219 216 214 213 1976-1980 209 204 200 1999-2004 199 195 194 0 1 2 3 4 5 Chang, Virginia and Diane Lauderdale. 2009. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50:245-260 Income Gradients for Total Cholesterol 1976-80 and 1999-2004: Predicted Lipid Levels from NHANES for Men 218 219 214 1976-1980 212 209 205 204 200 1999-2004 199 194 0 1 2 3 4 5 Chang, Virginia and Diane Lauderdale. 2009. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50:245-260 Medical Advances and Race/ Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Survival • Tehranifar, Neugut, Phelan, Link, Liao, Desai and Terry. 2009. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention. • Cancer cases (N=580,225) in SEER ages 20+ diagnosed with one invasive cancer in 1995-1999. • Used 5-year relative survival rates to measure degree to which mortality from each cancer is amenable to medical interventions (early detection and treatment) – ranged from 5% for pancreatic cancer to 99% for prostate cancer. Do Racial/Ethnic Differences in Survival Increase as Cancers become more amenable to medical interventions? 1.80 Hazard Ratio 1.60 1.40 American Indian/Alaska Native 1.20 Asian or Pacific Islander 1.00 African American 0.80 Hispanic 0 10 20 30 <<<<<Less Amenable 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 More Amenable >>>>> HIV Mortality • One potentially dramatic example might be HIV-AIDS mortality. • In particular Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HARRT) as a new life saving technology. HIV Mortality 1987-2005 • Rubin, Colen and Link. 2010. American Journal of Public Health • HIV mortality in every county in the United States from the National Center for Health Statistics by Age, Race and Gender. • Constructed rates for every year using mortality data for the numerator and census data for the denominator. • Constructed SES measures for each county using indicators of education, income, occupation and poverty. • We identified a pre (1987-1994), a peri (1995-1998) and a post (1999-2005) HARRT period. • We expect an interaction between SES and period and between race and period such that the benefit HAART is more pronounced in high SES counties and among Whites as opposed to low SES counties and among Blacks HIV Deaths among Whites per 100,000 by Age 40 30 15-24 years 25 25-34 years 20 35-44 years 15 45-54 years 55-64 years 10 5 Year 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 1989 1988 0 1987 Deaths per 100,000 35 HIV Deaths among Blacks per 100,000 by Age 160 120 15-24 years 100 25-34 years 80 35-44 years 45-54 years 60 55-64 years 40 20 Year 20 05 20 03 20 01 19 99 19 97 19 95 19 93 19 91 19 89 0 19 87 Deaths per 100,000 140 Incidence Rate Ratios – Blacks Versus Whites Before (Pre), During (Peri) and After (Post) the Introduction of Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy in the United States 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 7.84 5.64 White Black 3.66 1 Pre HAART 1 Peri HAART 1 Post HAART IRRs adjusted for age, sex, and SES and urbanicity of county of residence. Incidence Rate Ratios – Comparing a County at the 95th Percentile of SES to a County at the 5th Percentile of SES Pre, Peri and Post the Introduction of Highly Active AntiRetroviral Therapy (HAART) in the United States 4 3.5 3 2.72 2.5 1.91 2 1.41 1.5 1 1 1 1 High SES County (5th percentile) Low SES County (95th percentile) 0.5 0 Pre HAART Peri HAART Post HAART IRRs adjusted for age, sex, race, and urbanicity of county of residence 30 20 10 0 1985 1990 1995 Year 95% CI Fitted Values for Blacks 2000 Fitted Values for Whites 2005 Conclusions • When we examine Race and SES disparities in mortality by particular diseases we find dramatic evidence that such disparities are created over time. • Groups with more resources and who face less discrimination benefit more greatly from our new found capacity and disparities emerge • This means that explanations that propose relatively unchanging causes of disparities like genes, health selection due to health induced disability, relative deprivation, job control etc. cannot be the main reasons for health disparities. Colon, Rectum and Anus -- Age-adjusted Death Rates Per 100,000 1950-2000 34 32 30.9 30 30.6 29.2 28 Black 29.3 28.3 27.4 28.2 26.1 26 White 24 24.1 22.8 22 22 20.3 20 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 1995 2000 Age-, sex-, race-adjusted lung cancer mortality per 10,000 persons 45 years and over by county SES percentile, 19682005 Puzzles • Combinations of SES and gender, race, ethnicity, immigration status and sexual preference sometimes produces “paradoxes.” Understanding these paradoxes can be a door to newer and deeper knowledge. – Women disadvantaged compared to men but live longer. – African Americans disadvantaged with respect to SES but have lower rates of major depression. – Some immigrants groups --though disadvantaged with respect to SES -- enjoy longer life. Conclusion • Many prominent disparities are created when the benefits of new knowledge about disease causation and new approaches to prevention and cure are distributed unequally in populations. • The HERON’s Gaze needs to be fixed on these unequal distributions and it needs tobe ready to strike when the processes that enable their emergence are evident.