Philosophy: Ancient Greek & Stoicism - Key Concepts

advertisement

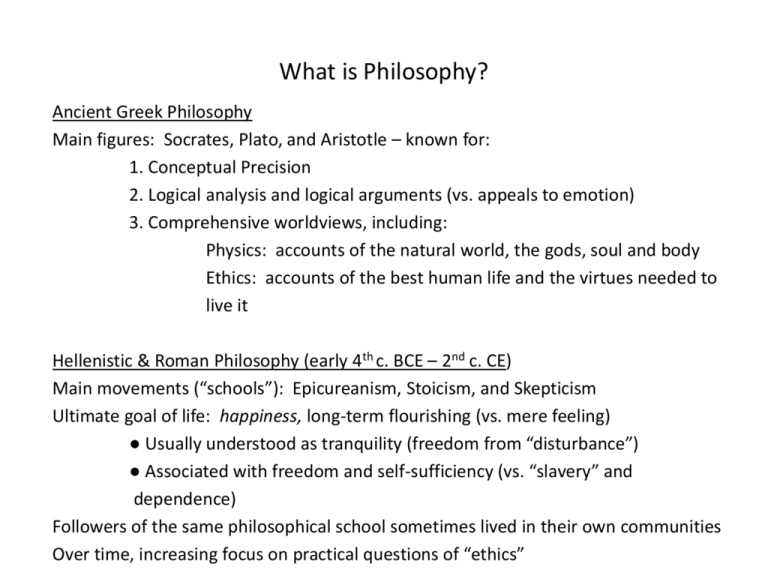

What is Philosophy? Ancient Greek Philosophy Main figures: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle – known for: 1. Conceptual Precision 2. Logical analysis and logical arguments (vs. appeals to emotion) 3. Comprehensive worldviews, including: Physics: accounts of the natural world, the gods, soul and body Ethics: accounts of the best human life and the virtues needed to live it Hellenistic & Roman Philosophy (early 4th c. BCE – 2nd c. CE) Main movements (“schools”): Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Skepticism Ultimate goal of life: happiness, long-term flourishing (vs. mere feeling) ● Usually understood as tranquility (freedom from “disturbance”) ● Associated with freedom and self-sufficiency (vs. “slavery” and dependence) Followers of the same philosophical school sometimes lived in their own communities Over time, increasing focus on practical questions of “ethics” Philosophy in the Modern Period (17th-19th c.) Increasingly “academic” (vs. a way of living) Increasingly distinguished from both theology and the sciences Still concerned with the basic assumptions of the sciences ● Examples: What is time? What is a biological species? An emotion? Still concerned with conceptual precision and logical argument Philosophy from the 20th c. to the Present Growing specialization within philosophy Fewer philosophers develop comprehensive worldviews Most philosophers work mainly in one or more subfields: ● Logic, philosophy of science, ethics, history of philosophy, etc. Stoicism ● Began in the 3rd c. BCE (Epictetus is a representative of later Stoicism) ● Influenced Christian, Islamic, and Jewish theology, though often indirectly ● Influenced early modern philosophy, especially Descartes and Spinoza ● Examples of present-day influence: ‒ Philosophy: Lawrence Becker, A New Stoicism (Princeton UP, 1998) ‒ Cognitive & Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy: Ronald Pies, Everything Has Two Handles: The Stoic’s Guide to the Art of Living (Hamilton Books, 2008) ‒ Military Education: ▪ James Stockdale, “The Stoic Warrior’s Triad” (1995) ▪ Nancy Sherman, Stoic Warriors: The Ancient Philosophy Behind the Military Mind (Oxford UP, 2005) Epictetus (d. 135) • • • • • • • • • Grew up as a slave during the Roman empire After being freed, became a famous teacher of Stoicism Addressed his teachings to ordinary people Apparently never wrote anything Teachings compiled by Flavius Arrianus (alias Arrian) Main work by Epictetus: the Discourses The Handbook: a highly condensed version of the Discourses Focused primarily on ethics, secondarily on physics (including theology) Problem of interpretation: Did he sometimes use common language, esp. about God, in order to make his teachings less shocking and more appealing to ordinary people? Key Distinction: What is Up to Us vs. What is Not Up to Us • • • • Our mental states: our opinions, judgments, desires, aversions, emotions, and virtues or vices By nature free, unhindered, unimpeded, our own Within our control Our freedom from harm and disturbance • • • • Everything else: our possessions, jobs, reputations, and even our own bodies Enslaved, hindered, weak, not our own Beyond our control Our own deaths Theory of Emotions and Value The ideal state of mind = apatheia, freedom from passion (vs. emotion or feeling) Whatever is good is beneficial under all circumstances Only our own virtue is good, and our own virtue is up to us Other things might have instrumental value but are still “indifferent” (not good or bad) Passions ▪ Always irrational ▪ Reflect the erroneous judgment that something indifferent is good or bad ▪ Examples: desire, exhuberance, fear, grief, anger, envy Good Emotional States ▪ Reflect rational judgments about what is good and bad ▪ Do not cause disturbance ▪ Examples: wish, joy, caution ▪ No rational counterparts of grief, anger, envy What is the Central Argument? The most important advice is: “Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well” (sect. 8). This itself is not an argument because arguments have premises and conclusions, all of which must be true or false. Any statement in the form of an imperative, such as “Do not seek. . . .” is neither true nor false. The advice can be reformulated as an argument that meets logical requirements, but to find all the necessary premises we must look beyond sect. 8: P1. If you want your life to go well [= If you want to be happy], things must happen as you want. [Part of sect. 8 transformed from an imperative into a conditional: If x, then y] This premise is generally regarded as true because: You do want your life to go well. [Everyone wants happiness, even if disagree about what happiness is.] Being happy = Having things happen as you want. [Widely accepted view of happiness.] But if you want to be happy, and if happiness = having things happen as you want, why should you not seek to have them happen as you want them to? The answer lies in Sect. 1, which provides two more premises: P2. How things happen is not up to you. P3. What you want is up to you. The Central Argument Reformulated P1. P2. P3. C1. If you want your life to go well [to be happy], things must happen as you want. How things happen is not up to you. What you want is up to you. Therefore, you should either (a) Want things to happen as they do happen (sect. 8), or (b) Want nothing at all. (See section 2: “And for the time being eliminate desire completely. . . ”) Option b is for people making progress. It won’t make you happy, but it will ensure that you are not “unfortunate,” and this is necessary in order to become a sage. Only the sage is capable of a: wanting things to happen as they do happen. Therefore, only the sage is truly happy.