8 reading and writing science 060708(1)

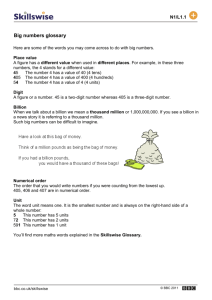

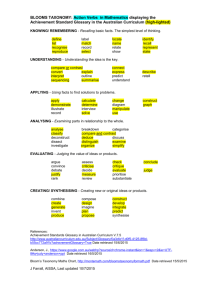

advertisement

Welcome, once again, to the Natural Inquirer Writing Course Session 11: Reading and Writing Science In the first part of this session, we will focus on reading science. The Natural Inquirer is unique among science education resources primarily because of its focus on reading science. In the second part of this session, we’ll start exploring how to write a Natural Inquirer article. Let’s start this session by -- you guessed it -- reading! The following essay was written by Dr. Stan Metzenberg, California State University Northridge. There is no date on the essay, and you will read only a part of what was written. It has become fashionable in science education to mold K12 students around an idee fixe [obsession] of a modern scientist; formulating hypotheses, observing, measuring, and discovering through hands-on investigations. What has been left unsaid is that real scientists don’t actually spend very much of their day “observing” and “measuring.” They read! Reading for understanding of content is the core process skill of science, and there is no substitute for practice at an early age. A student who has not developed the skill of learning through reading has no professional future in science. Without a foundation in scientific vocabulary and with minimal knowledge of scientific fact, their words bear an accent of ignorance that is impossible to conceal and nearly impossible to remediate. While young people should be encouraged to enter science, they must also be given the education that will permit them to succeed. Hands-on investigative activities ought to be sprinkled into a science program like a “spice;” they cannot substitute for a “main dish.” The best “hands-on” program would be one in which students can get their “hands-on” an informative textbook! Dr. Metzenberg may be undervaluing the contribution of hands-on learning, but he certainly is not over-stating the importance of reading science. There is no question that hands-on investigative activities are an important part of the science curriculum. However, providing hands-on investigation without the other process skills that make up the entire scientific process gives an unbalanced science education and robs students of the knowledge and skills to successfully complete an entire scientific investigation, or to understand an investigation completed by others. Now, let’s continue our reading exercise with another essay on reading science. This was written by Dr. Patricia Bowers, Associate Director, Center for Mathematics and Science Education, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Just like peanut butter and jelly, science and the communication skills of reading and writing are natural partners for today’s classroom. The teaching of science concepts combined with communications skills is an approach whose time has come. …To meet the needs of the compacted day, it is necessary to teach "smarter"—to teach more in the same amount of time. One way to do this is to implement an integrated curriculum where more than one subject is taught at the same time. Science and reading complement each other well because of the similarities between reading skills and science process skills. The meshing of the skills in both subject areas make them natural partners for integration. For some skills, such as identifying main ideas and details and classifying, different terms are used to describe the same process. For other skills, such as drawing conclusions, the terms and processes are the same for both subject areas. In the illustration on the following slide, Dr. Bowers shows how science, reading, and writing process skills align. For our purposes now, we focus on science and reading process skills. However, writing process skills can be practiced through the Natural Inquirer’s FACTivity section. As you examine the next slide, make notes in your notebook about the similarities in science and reading process skills. Don’t forget to think about how you might use writing process skills in a FACTivity or a lesson plan! (See example below.) From “Moving Spore-adically,” Invasive Species Edition FACTivity: Write a story for your children about living with oak trees. If you have a favorite oak tree, you can write about that tree. You could tell about climbing an oak tree or building a tree house, or you could write about that one big oak tree standing alone in the park. You may include drawings with your story. Comparison of Science, Reading, and Writing Skills (P. Bowers) Science Reading Writing Classifying Identifying main idea/details Outline science information Experimenting Sequencing Write up a procedure to use Drawing conclusions Drawing conclusions Study experiment results and write up what you think happened based on the facts Writing up experiment results Expository writing After conducting an experiment, write up the results Observing/inferring Distinguishing cause and effect List causes and effects in a given experiment Determining cause and effect Determining cause and effect List causes and effects in a given experiment Comparing and contrasting Comparing and contrasting Prepare a chart that gives similarities and differences between two similar organisms In these initial sessions, you are building a foundation of knowledge that will be applied later as you write your first Natural Inquirer article. As you go through these slides, please think reflectively and make notes in your notebook. In particular, always think ahead and ask yourself…. How can I apply this knowledge to writing a Natural Inquirer article? Preparing to write at the 7th grade level It’s not easy being green. It’s also not easy writing at a 7th grade level. Use the following guidelines when you are writing for middle school students: • Keep sentences short. Make them as short as possible. Maximum sentence length should be between 14 and 22 words. For reference, the average sentence length in a Reader’s Digest is 15 words. • As many words as possible in an article should be one or two syllables. This is a challenge when writing a scientific article! For reference, an average Reader’s Digest contains about seven percent hard words. • TV Guide and Reader’s Digest, with the largest circulations in the world, are written at a 9th grade level. USA Today is written at a 10th grade level. You will need to write more simply than a TV Guide! How can you figure out what writing looks like at a 7th grade level? • You can read a middle school textbook. • You can read excerpts from the following authors: 1. John Grisham 2. Tom Clancy 3. Stephen King 4. Frank McCourt 5. Michael Crichton •You can read a Natural Inquirer! From Frank McCort, ‘Tis (1999): When the MS Irish Oak sailed from Cork in October 1949, we expected to be in New York City in a week. Instead, after two days at sea, we were told we were going to Montreal in Canada. I told the first officer all I had was forty dollars and would Irish Shipping pay my train fare from Montreal to New York. He said, No, the company wasn’t responsible. From Michael Crichton, Timeline (2000): He should never have taken that shortcut. Dan Baker winced as his new Mercedes S500 sedan bounced down the dirt road, heading deeper into the Navajo reservation in northern Arizona. Around them, the landscape was increasingly desolate: distant red mesas to the east, flat desert stretching away in the west. They had passed a village half an hour earlier- dusty houses, a church and a small school, huddled against a cliff- but since then, they'd seen nothing at all, not even a fence. Just empty red desert. They hadn't seen another car for an hour. Now it was noon, the sun glaring down at them. For more examples, you can search for excerpts from these authors and other sources on the Web. For example, From “America’s Dumbest Criminals, Reader’s Digest: As fantasies go, Jose Santiago, Jr., had a rather strange one. Too bad he decided to act it out. One Sunday evening in April 2006, the 33-year-old decided his hometown of Gurnee, Illinois, could use one more cop. Guess who? It would help his charade that he had bought an old police car -- a 1999 Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor -- and mounted red and blue lights on its dashboard. When a driver pulled into Santiago's apartment complex, the rookie was ready for his baptism. He blocked the guy's car with his own, then motioned him over. A slender man with short, dark hair walked up to him, puzzled. Although words should be kept as simple as possible, with scientific writing this is not always possible. When you run into the inevitable more complex word or term, each Natural Inquirer article has…. ….A Glossary •The purpose of the glossary is to provide a short definition and pronunciation guide for new words. •Most of these words are scientific or are related to natural resources. Use only the definition appropriate to the article. •Keep the glossary as short as possible. Limit is 12 words. •Diacritical marks help students to correctly pronounce the word. •Diacritical marks used in the Natural Inquirer are special. They were created because the layout artist did not have access to proper diacritical marks. •Therefore, the pronunciation guide must be included with the glossary list. See a Natural Inquirer article for an example. Glossary, continued…. •As you write, when you encounter a word that should be defined, italicize its first occurrence in the text. •If, at the end of your writing you find you have more than 12 glossary words, go back through your text and eliminate as many glossary words as possible. Substitute simpler words. •Glossary words should be those that are used more than once in the text. In other words, do not include a glossary word just to teach a new word. The word should be central to the research story, and it should be so critical as to not be substitutable. Glossary, continued… How do you know if a word should be included in the glossary? This is difficult to say. You can check the Natural Inquirer Web site glossary list to see if the word is already there. (The glossary list can be found on the Natural Inquirer web site.) If it is there, include it on your list. Otherwise, err on the side of caution. If you question whether a word should be included, either substitute a simpler word or include the word in the glossary list. Remember, include words that cannot be easily substituted and are central to the research paper. We want students to understand the article! If you question whether a word should be included, either substitute a simpler word or include it in the glossary. Pronunciation Guide a as in ape ä as in car e as in me Special characters, such i as in ice as ä and ô, are found in o as in go ô as in for Word under “insert” u as in use then “symbol.” ü as in fur oo as in tool ng as in sing Accented syllables are in bold. Paragraphs When a Natural Inquirer article is used in the classroom, it is often read aloud paragraph by paragraph. Keep paragraphs short. If possible, each paragraph should contain no more than 6 sentences. Remember that students from grades 5-10 read the Natural Inquirer, although our target grade is 7th. Some students will read and comprehend at a lower level (remember too the developmental range of adolescents). Writing a Natural Inquirer article requires a balance between providing challenging reading for all students. Help less skilled readers by giving simple definitions in the glossary. More skilled readers can skip reading the glossary, if they already know the word. You can check and adjust the reading level of your text by using the Lexile Framework for Reading: The Lexile Framework for Reading is a scientific approach to reading measurement that matches readers to text. The Lexile Framework measures both reader ability and text difficulty on the same scale, called the Lexile scale. This approach allows educators to manage reading comprehension and encourage reader progress using Lexile measures and a broad range of Lexile products, tools and services. (From the Website, http://www.lexile.com) To access the Lexile text analyzer, visit: http://www.lexile.com/DesktopDefault.aspx?view=ed&tabindex=2&tabid=16&tabpageid=335 Remember, keep your writing short and simple. Good luck! Method The scientist used eggs that came from Eastern Europe (figure 3). She incubated the eggs (figure 4), which caused them to hatch into larvae (figure 5). She divided the larvae into two groups. The scientist observed the first group of larvae for the first 14 days of their development. She observed the second group of larvae through their development into pupae. Figure 4. Nun moth eggs being incubated in a mesh packet. You can see the mesh packet and eggs inside the petri dish. From “And Then There Were Nun,” from the Invasive Species Edition. Note the short sentences and glossary words italicized. Congratulations! You have completed Session 11 of the Natural Inquirer Writing Course!