ZANELLE%20DISSERTATION%20-VERS

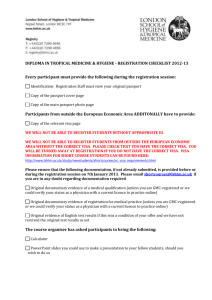

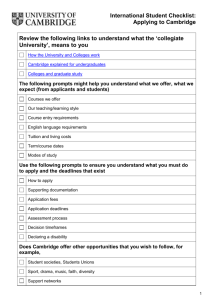

advertisement