Background I understand diffusion within social movements to be

advertisement

Draft on Anti-Fracking

I.

Introduction

The recent uprisings of the Arab Spring signaled to observers, activists and scholars of

social movements alike the fundamental place of diffusion dynamics within social

movements. From Tunisia to Egypt the fall of authoritarian regimes due to mass

mobilizations and collective action indicate the centrality of the spread of idea, tactics and

personnel to the experience and the study of social movements. The spread of ideas,

tactics and personnel has long been a focus of study within scholarship on social

movements (Tarrow, 1989; Tarrow and McAdam, 2005; Tilly, 2004; Whittier and Meyer,

1997; Wood, 2012; Chabot, 2002; Chabot and Duyvendak, 2002; McAdam and Rucht,

1993). Dynamics of tactical learning within the flow of movement forms, particularly the

transnational spread of tactics has been a recent significant concern of social movement

scholarship (Hertel, 2006; Thorn, 2005; Tarrow, 2005; Wood, 2012).

The current public debate about energy production in the United States tends to focus on

the production and use of petroleum. However, often over looked is the extent to which

the United States generates a significant amount of its energy use from natural gas. In

2011, the United States used roughly 25% of its energy from the extraction of natural gas1

based on technological innovations that have made gas drilling more efficient than

previous eras of energy production. New technologies for drilling and gas extraction,

known as “hydrofracking” include drilling into rock with a combination of water, chemicals

with application of intense pressure in order to “frack” or break the rock and release the

1

US Energy Information Administration report, 2011.

1

Walsh-Russo

desired natural gas. The US Energy Information Administration reported that in 2010 the

increase in the number of drilling sites combined with the increased technological ease—

and relatively low cost--of gas extraction through “hydrofracking” created an increase in

demand of natural gas nationwide. The increase in natural gas extraction and use

(primarily for electricity) has also coincided with an increase in the cost of the most

significant energy source for the United States—a rise in the price of oil. The number of

potential locations for the possible “hydrofracking” of natural gas within the contiguous

United States is around nineteen shale formations, with among the most visible antifracking campaigns in the United States targeting the Marcellus Shale. The Marcellus Shale

is a formation that stretches from upper Tennessee to upper New York State and into

Canada (Article TKTK and EIA report, 2010; see Map I). As significant as the rise of fracking

for energy production may be for energy observers, equally pressing for analysts of

collective action is the concurrent rise of resistance against the use of hydro-fracking by

local communities throughout the United States, from Colorado to Ohio to New York State.

Encompassed with the rise of anti-hydrofracking moblization is the dynamic relationship

between activists against fracking and the recently visible and organized Occupy

Movement. In addition, anti-hydrofracking mobilization is frequently written about and

understood in the American press as a movement localized and contained within rural

communities. Despite its grounding in local—and often rural-based rhetoric and tactics—

anti-hydrofracking is a global campaign that has spread nationally within the United States

and internationally, with anti-fracking campaigns organized in Great Britain to Ireland to

France to South Africa among other states. The following discussion will draw out the

history of anti-fracking within the United States through an account of its domestic

2

Walsh-Russo

mobilization, particularly with respect to tactical ties to Occupy and discuss its loose

affiliation as a possible—although not fully formed--transnational advocacy campaign. The

recent wave of anti-fracking protests within and outside the United States may direct

scholars of contemporary contentious politics to investigate evidence of tactical diffusion

processes and allow further examination of a transnational tactical repertoire (Wood,

2007; Tarrow?).

II.

Literature: What is diffusion? How have scholars understood diffusion

processes?

Scholars of social movement dynamics are embedded within a long analytic tradition of

theoretical and empirical research on diffusion and spillover of protest cycles, tactics,

personnel (Tarrow, 1986 TKTK; McAdam and Rucht, TKTK, Whittier and Meyer, 1997 TKTK).

The case study of recent anti-fracking dynamics, particularly anti-fracking connections to

Occupy tactics, personnel and rhetoric domestically as well as burgeoning anti-fracking

mobilization internationally may further reveal findings into transnational diffusion with

respect to the dynamism within an available transnational tactical repertoire. The global

protest events of 2011 also remind us that the spread of tactics among members and

organizations working for social change is a long standing tradition within the world of

states. While journalistic accounts of the Arab Spring and Occupy! tend to emphasize the spread

of tactics as contagious “wildfire,” analysis of the spread of ideas and tactics has a long

standing place within the social sciences more broadly and the study of states and

social movements more specifically. The tradition in social movements in particular has

been grounded in challenging and unpacking the often accepted notion of “contagion.”

3

Walsh-Russo

Diffusion or the spread of an idea or thing within social science research may be

understood as the spread of something across social institutions and through social

networks. The greater the expansion, the greater the number of individuals affected

(Soule and Strang, 1998). Sufficient studies of diffusion most often provide answers to

question they are addressing with regards to the dissemination of an innovation (an

item, idea or practice) to adopters {individuals, groups, corporate units) through

modes of communication, social structures (networks, community, class) and social

values or cultural practices (Katz 1999:147). The categorical dichotomy between groups

that create diffused items and those who receive those items, and analysis surrounding

the interaction between the spread of an item and the reception within a local

population has a long standing tradition within social science and the study of social

movements. Diffusion studies proliferated throughout the social sciences during the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, linked by their fundamental search for

explanations and descriptions of social change. Early works on diffusion examined the

spread of a newly acquired item or idea over a single geographic region {Rogers, 1962).

The early paradigmatic models of the diffusion process held that the adoption process

of an idea or thing moved from one stage of adoption to the next, and thus provided

conditions for seemingly fluid acceptance or rejection of a particular innovation,

transmitted--and either adopted or rejected--by structurally equivalent actors.

Cultural symbols and meanings were understood most often as exogenous to diffusion

processes. Research on diffusion within social movements often mimicked the

relationship between cultural processes and structure found within broader social

science diffusion research. Thus, the first studies of diffusion within social movements

4

Walsh-Russo

rarely explored the particular cultural and social conditions that led to the transfer and

exchange of ideas, practices, strategies, organizational forms, and personnel between

and among movements {Guigni, 1999). The basis for cultural elements within diffusion

processes was understood as a residual category used to explain differences in

diffusion processes within different contexts (Giugni, 1999). The study of diffusion within

social movements became an important interest for sociologists of collective action and

contentious politics as evidence from the Civil Rights era and afterwards indicated how

participants drew influence and information from other participants and organizations.

Analysts drew on the theories and methods of early diffusion theorists (Rodgers, 1995;

Lazarsfeld, 1956) and constructed models of diffusion that continued to rely upon earlier

social science studies and their assumptions of how an idea or thing spreads across a

population. In turn, collective action was often understood as an irrational response to

collective strain. The analytic lacunae left important questions unanswered. In response,

sociologists and other social scientists attempted to fill these empirical and theoretical

gaps. Research with an emphasis on interpretive work emerged, garnering attention

towards the effects of cultural processes and mechanisms in determining the shape and

definition of diffusion processes. For studies of diffusion within social movements, this

cultural turn meant more precise theorizing on how actors incorporate meaning, how

they make sense of themselves and others, how social norms alter the spread of an idea

or thing (Jasper and Poll etta, 2001; Strang and Soule, 1998). Furthermore, the evolution in

diffusion studies within research on social movements also meant the generation of

macro-level analysis regarding the effects of diffusion on organizations and collectivities.

5

Walsh-Russo

Trends in diffusion studies and social movement research evolved into answers for

two sets of questions. The first set of questions concerns "Itself with the processes and

mechanisms that create diffusion. What are the various processes through which a

movement's action and organizational forms diffuse? What is the status of these

processes--direct or indirect? What kinds of indirect and direct ties may be most

important for diffusion? Specifically, how might political opportunities and the role of

the state affect diffusion processes? What role does the media or press play in

displaying, transmitting, and shaping repertoires that diffuse? Are groups able to

adopt only from similar groups? What forms of similarity might be most salient and

useful for groups?

The second group of questions concerned the consequences of diffusion. What

are the advantages and disadvantages of diffusion? When and how are groups

advantaged or disadvantaged by adoption? How would advantages of diffusion

manifest among action forms, in terms of tactics, collective identity, and a movement's

sense of efficacy and validity? How would disadvantages of diffusion shape a

movement's self-perception, as reliant and unoriginal? Are repertoires diffused

through only discrete elements or the entire repertoire? propose answers to both

categories of analytic questions on transnational tactical diffusion. Instead of an

analytic focus that examines only the processes and mechanisms within diffusion or the

consequences on a movement of tactical diffusion, the case studies (Chabot, 2001;

Chabot and Duyvendak, 2002) draw on expand the analytic scope to encompass answers

to both sets of queries. In his analysis of transnational diffusion, Chabot (2001) draws

6

Walsh-Russo

on the by now familiar distinct stages of diffusion are no longer applicable to the study

of transnational social movements. Given that elements of a particular repertoire are

what most

often diffuses and not the entire repertoire, and that these elements do so at

different times in a protest cycle, staging as a method and a framework of

understanding diffusion fails to capture the processual components of diffusion.

Furthermore, as recent research demonstrates (Chabot and Smith, 1999, Tarrow, 2002,

Wood, 2003, Wood 2009?) movements that organize and coalesce across nation states do

so not as separate and self-contained entities, but as connected and dynamic sites of

action. The patterns and conditions of dynamism within these contested sites-and the

links between domestic or national sites and transnational actors' actions-need further

investigation and understanding within the transnational social movement literature.

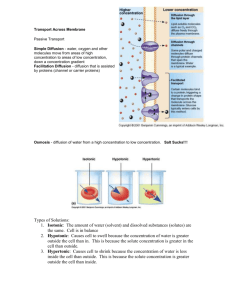

Background

I understand diffusion within social movements to be the spread of three

phenomena:1) individual motivation for participation in social movement activity 2) action

forms, that is, the repertoires of strategies, tactics, ideological and emotional commitments

of a movement 3) and organizational forms, that is, the particular chosen organizational

structure amongst a group of activists. Mechanisms that allow for the transfer of these

forms include social networks, encompassed by both direct and indirect ties, and

brokerage involving third parties that help facilitate diffusion. Research on social

movements and diffusion has most recently begun to grapple with the space and

7

Walsh-Russo

temporality of transnational social movements. Within such movements, where might

cultural references come- from? How can we theorize on the relationship between

information flows and the exertion of power within transnational movements? What other

processes maybe at work besides just the necessary requirement for shared references

and mutual identification? Theoretical and empirical studies on the proliferation of social

movements operating across nation states mount significant challenges to traditional

hypothesis found within the study of social movement diffusion and indicate that

application of these assumptions to social movement analysis demands reformulation

and rethinking. Analyses of transnational social movements led recent scholars towards

further understanding of the particular social conditions that creates diffusion within

social movements, with an emphasis on how political opportunities within a domestic

context shape the availability and success of tactical diffusion (Walsh-Russo, 2008). Early

studies of diffusion research within the broader social sciences emphasized diffusion of

three conditions: 1) flows of information 2) the effects of class hierarchy, power and

influence, and 3) public opinion (Giugni, 1999). Among early theorists, several

fundamental assumptions emerged. First, diffusion as a set of five stages also follows

discreet rules (Chabot: 2002). The staging model was developed as a predictor of the

increase in individuals adopting an innovation after passage of each time period, with

adoption rate increase following the stages of experimentation and adaptation

(Rodgers, 1995: 23; Chabot, 2002:107). 1 The early staging model explicitly links diffusion

of an idea or thing with "newness" and innovation of adaptation. Yet, theorizing on

how adaptation takes place is left unexplored. Instead, early works on diffusion

8

Walsh-Russo

emphasized the importance of compatibility 2 between the thing being diffused across

a population and the sociological and psychological condition of the adopter or group

of adopters (Katz, 1999:149; Tarde, 1903).

1 Sorokin's theories on diffusion included a critique of the S curve, and argued against its

assumption of universalism. Instead given the myriad of diffusion processes, Sorokin

argued, several S curves might exist. (Katz, 1999: 151).

2 The saliency of similarity and compatibility between adopter and transmitter to the

successful diffusion and adoption of an idea or thing continues to be a fundamental

assumption within diffusion research today. See Snow and Bendford,1999.

For early theorists, the most successful cases of diffusion and adoption occurred when

the thing or idea being diffused was most similar to pre-existing structural and cultural

conditions (Tarde, 1903, 1989; Katz, 1999). Moreover, early diffusion theorists argued

for the downward movement of an innovation with regards to social class-an

innovation was assumed to have originated within the dominant upper class and

adopted by subordinate middle and lower classes (Sorokin, 1941). Sorokin's studies of

mobility depict diffusion of an idea or thing often imposed upon by those more

powerful, sometimes adopted unknowingly, and, at other moments, with awareness

by the less powerful. Thus, he offers an account, however flawed, of working class

domination and agency. In this sense, Sorokin echoes Simmel's top-down diffusion

model of fashion, of upper class construction and development of trends and lower

9

Walsh-Russo

class adoption and absorption of those trends (Crane, 1999: 15; Simmel, 1904).

Classical studies eschewed in-depth analysis of cultural practices. In turn, theorists chose

an emphasis on structural mechanisms, such as social networks, that promote internal

diffusion of new information flows, ideas and things within a discreet population (Strang

and Soule, 1998). Because classical studies emphasized sameness, similarity and mutual

identification as fundamental conditions for diffusion within a population, the intrapopulation analysis of classical studies emphasized strong, dense ties amongst

members of a group as a fundamental (structural) mechanism for the transmission of

new information and things.

10

Walsh-Russo

Burt's analysis of structural equivalence (1987) finds that actors within shared, similar

networks often develop competitive strategies for maintaining relations within that

network or tie. Meyer and Strang (1993) argue that during diffusion and subsequent

adaptation actors consider the successes and failures of previous actors' activities.

Modern nation-state legitimacy often rests on conflicts surrounding the elaboration or

restriction of assumed universal rights, articulated through state policies, and often

relying on the support of scientific knowledge. Thus, given the role of the nation-state in

facilitating these values and beliefs, diffusion of innovations in the form of state policies

creates a flow in which innovations are easily expanded. Commonly held assumptions of

modern life-for example, universal rights, the importance of science-allow actors to

engage in competition wi th other actors and share common categories and identities,

together with common, collective understandings and shared meanings. These

similarities provide a foundation for diffusion of new information, ideas and things.

(Meyers and Strang, 1993).

The works of earlier and later classical diffusion studies contributed key insights for

studies of diffusion within social movements and provided researchers with

fundamental assumptions and models to be used as guides for future research. Within

research conducted on social movements and diffusion, findings have helped

contribute to explanations of what types of processes and mechanisms allow for the

successful transfer and adoption of individual participation, action and organizational

forms across and within populations (most often, although not exclusively,

organizations formed and maintained outside formal, mainstream institutions).

11

Walsh-Russo

Moreover, research on diffusion within social movements offered theoretical

contributions to understanding the outcomes and consequences of diffusion. Empirical

and theoretical studies on diffusion within social movements also drew on

interpretative work outside of the social sciences, and thus developed nuanced

analysis of what types of practices diffused across macro- level institutions. Framing

theorists examined how diffusion processes were transformed by interpretations and

meanings held by actors. 3 Drawing on these approaches, the relatively new study of

transnational movements has brought to the theoretical and empirical foreground

questions on the successful diffusion of new tactics and strategies where similarities

between structural position and shared cultural symbols may remain ambiguous

amongst participants. Sociological and political science literature on the study of

contentious politics has increasingly been concerned with questions regarding the

"building blocks" of theoretical construction on transnational diffusion (Hertel, 2003).

The literature may be divided into four components: 1) networks, direct and indirect

ties, and spatial similarities 2) brokerage 3) contagion and 4) cycles of contention and

protest.

,

Diffusion between two channels depends not only upon rational calculations and

interpersonal relations between individuals but also upon the influence of indirect,

non-relational conductors of innovations4 such as various forms of mass

communication. Information may spread across nation states through non-direct ties

when personal relations are not available, provided an analogous self or collective

identity exists between transmitters and adopters.

12

Walsh-Russo

3 Also thereby offered critiques of many of the theoretical foundations underlying classical

diffusion theories.

4 Doug McAdam and Dieter Rucht

13

Walsh-Russo

Two categories along which innovations may flow: direct {network, structural, relational

ties) and non-direct (termed "cultural linkages") channels (Meyer and Strang, 1993).

Meyer and Strang's study of diffusion within social movements emphasized the

temporal dimensions of diffusion as well as the cultural constructions of meaning that

occur before, during, and after the spread of social entities. Epiphenomenal changes

such as the rise of the modern nation-state, the role of scientific theorizing and the

salience of modern scientific practitioners are crucial variables in ensuring the

institutionalization of scientific thought. 5 The rise of institutions such as universities, as

well as the rise of the modern print media, helped ensure the subsequent ease with

which scientific knowledge and theorizing were passed on and spread to a wider

population. Specifically, Meyer and Strang argued that the modern development and

specialization of analytic concepts and categories, the examination of patterned

relations6promotes and speeds up the processes of diffusion within cultural domains7

Tilly's analysis of protest and contention among British workers during the late 18th and

early 19th century introduced repertoire-s of contention into the study of collection

action and social movements (Tilly, 1992, 1994, 1995). Repertoires of action develop

contentious elements when the outcome of claims

5 Meyer and Strang write, "one reason for emphasizing the sciences and professions is that

thes e communities are relatively central, prestig'1ous, influential, and so not o-nly

construct models but are able to promote them vigorously...diffusion...requires support

14

Walsh-Russo

from other kinds of actors...state authorities, large corporate actors,grass-roots activists.

In some way,models must make the-' transition from theoretical formulation to social

movement to Institutional imperative (Ibid,p495)."

6 Ibid, p492.

7Relatedly,Meyer and Strang's early work emphasized the spread of public policy and

other forms of group innovation across nation-states.

maintained by leaders and followers impact the interests of claims-makers (Tilly, 1994).

The spread of contentious repertoires (through interactions of group practices) is

highly constrained by dynamics between claims-makers and actors acting on behalf of

institutions such as the state. Thus, an important component to the diffusion of

repertoires of contention is the struggle between actors. In addition to Tilly, Clemens

(1996), Tarrow (1994) Meyer and Tarrow, (1998) also argue that the spread of

innovation contains a performative mix of "newness" in order to generate notice from

audiences as well as the references, for audience comprehension, to previous

repertoires, (Krinsky, 1999: 2). As Tilly notes, most new innovations die quickly, and

those that survive often operate on the margins of social life. Furthermore$ for claimmakers, successful outcomes help ensure the survival of a repertoire.

Clemens' (1993; 1996) research on American social movements of the late 19th century

draws on Tilly's notion of repertoires as well as the work of neo-institutionalists

15

Walsh-Russo

(DiMaggio and Powell, 1991} and expands on the notion of repertoires as sets of

interactions through examination of social movement organizations' interactions with

institutionalized, state processes. Clemens argues that social movement

organizations draw upon organizational forms that are simultaneously innovative as

well as known, and thus create repertoires of organizational practices. Through the

adoption of familiar and unfamiliar innovations, social movement groups are not wholly

incorporated into the state apparatus, yet nevertheless shape and alter their political

landscape through organizational innovation and creativity that in turn makes available

those innovations to newcomers.

16

Walsh-Russo

The effects of interaction between the state and social movements are also McAdams'

(1994) focus in his conceptual development of spin-off and initiator movements. Spatial

and ideological overfap may lead to the creation of a social movement community, in

which cultural practices from one movement, such as writings, music and art are then

shared and incorporated by another, linked group. While sympathetic to political

process accounts of diffusion provided by McAdam and Rucht, Meyer and Whittier point

out that within the broad public sphere spin-off and spill-over movements draw upon

previously established activist networks for help with establishing new causes,

resources and external support. For example, women from the 1970s feminist

movement were able to use pre-existing activist networks as well as current

employment opportunities-- in politics, Jaw and research foundations, as examples--to

raise financial and ideological support for the emerging anti-nuclear movement of the

late 1970s and 1980s (Meyer and Whittier, 1993). Whittier and Meyer's analysis of the

relationship between feminist and anti-nuclear movements demonstrates the

interaction between the formulation of a collective identity and the diffusion of

practices and ideas. The process of forming communities and enacting collective

identities among group members means developing not only a sense of the groups and

ideas "we" are against, but also who "we" are a part of, the coalitions and groups "we"

are also simultaneously in alignment (Jaspers, 1998; Polletta and Jaspers, 2001). Social

movement communities and activist identities are formulated not only in response to

opposition parties, but in dialoging, speaking and linking to other, emergent

movements similar to their own.

17

Walsh-Russo

Transnational social movement diffusion

As theorists of social movements and diffusion have recently incorporated into their

analyses, technological changes in mass communication and transportation and

subsequent changes among ties between individuals have deepened the intensity and

speed of diffusion, and help account for the spread of a movement's tactics, identities and

goals (Tarrow, 2006). Recent studies on social movement diffusion have also attempted to

capture the specific dynamics that account for the types ofties and spread of a movement

across geographic expanse. Soule's (1995) analysis of shantytown tactics among US college

students expands upon the preliminary findings of McAdam and Rucht's research on the

conditions of cross- national activist networks among the US and German New Left. Soule's

findings on the spread of a particular tactic among college students of similarly ranked

institutions indicate that the strength of indirect ties contributes significantly to the

solidification of a group's collective identity (Soule, p873). According to Soule, the

shantytown tactic diffused across particular higher education institutions, ones that shared

similar structural location as elite, well-endowed, wealthy colleges and universities. Soule's

analysis underscores the connection between similar networks, ties and the establishment

of a sense of solidarity and shared "we-ness" in helping diffuse ideas and practices within

social movement organizations. The construction of shared solidarity and similarity between

transnational dimensions within a set of connected movements is often arrived at, if at all,

through struggle and contestation. Wood provides an (2001, 2003, 2007} account of internal

strategies within recent anti-globalization organizations. Based on observations of

18

Walsh-Russo

organizational meetings, Wood argues the asymmetric relationship between the global North

and South is recreated within the anti-globalization movement's internal relations.8

8 Wood discusses tensions within PGS surrounding undetermined decision-making

processes. One source is the frequent suggestion of the Northern activists to base decisionmaking on consensus.

Beginning with prior organizational and movement experience, participants often bring

divergent knowledge and accounts about the role of social movements in relation to the state

to movement meetings. Wood finds Northern participants frequently involved in anarchist,

direct action, peace and environmental movements, while in the South, participants are

involved with the work of unions, peasant and indigenous movements. Frequently, these

structural dissimilarities, the lack of shared or similar backgrounds and experiences among

participants create conditions through which the construction of similarity and thus coalition

building and the spread of tactics become difficult t_o negotiate. How do these contemporary

transnational movement actors, Wood questions, while acting· in broad coalition with other

actors, strategically respond to particular political and economic contexts and struggle to

maintain ideological commitments that must traverse local and national geographic,

economic, and cultural spheres? Smith's (1997) findings indicate that the more cohesive a

network of transnational organizations within the environment or locale of other transnational

organizations, the greater the facilitation for movement actors to overcome various challenges

and constraints to transnational organization and mobilization. Smith notes in her study that

19

Walsh-Russo

the density of transnational social movement networks within their environment with other

international organizations and non-governmental organizations is increasing-given their

geographic dispersal and frequently overlapping membership. Smith's and Tarrow's (2006)

analysis on the personnel and organizational overlap within the field global organizations

indicates, within the complex world of state borders and non-governmental organizations,

changes or transformations that occur within the transnational space of some social

movements are never complete and the continuation of transformations never secure.

The space or location beyond, above or across state boundaries is continually formed and

reformed. That is, transnational social movement organizations work constantly to

reestablish the realm or space through which their work is done, above or beyond the

broader world of individual sovereign states through which they must also interact and

grow. Leila Rupp's (1997) analysis of early twentieth century transnational women's peace

organizations details an earlier, more nascent version of the transnational sphere and the

work activists devote to its preservation. Rupp's historical account presents how, at least

for the cadre of leaders, friendship ties facilitated by internal interlocutors, established

long standing connections among women participants located geographically throughout

Europe. The close, almost- familial, quality of the social ties among women leaders helped

form a transnational space founded upon the recognition of, even celebration of through

various rituals, participants' preexisting national identities while simultaneously also

advancing international normative understandings of war, peace, and gender. Within

these early forms of transnational organizing, participants' rigorous political engagement

helped develop the template, Rupp argues, for a contemporary transnational collective

20

Walsh-Russo

identity, that is, their work modeled the balance of national with international political

identities, soon after realized in post war international relations with the formation of the

United Nations, as the largest and most influential of international organizations. Thus, the

international women's movement's influence, like much of transnational political organizing

that begins with the abolitionist movement in the late 18th century, extended beyond their

European locale and the historic context of their mobilization attempts.

The internal dynamics of a movement that help extend activist networks, information and

material resources beyond state borders affects the development and maintenance of

amorphous and elusive transnational space.

Thorn's (2009) study of the South African anti-apartheid movement of the mid twentieth

century analyzes the transnational features of the movement, the influence of external and

internal actors on different movement tactics and organizations. Similar to Rupp's analysis of

international women's organizations, anti-apartheid activists' from the 1960s to the 1990s

work through boycotts and sanctions, divestments and disinvestments, drew on both face to

face interactions between key activists as well as in broad coalition with other, external actors.

Thorn documents the influence of the US based Black Power movement on the South African

movement. The outside movements and social ties that helped construct an imagined

community of solidarity activists outside of the state boundary of South Africa helped build

sustained transnational anti-apartheid actions across borders. As the international antiapartheid movement worked through the system of nation states as well as the increasingly

intensified processes of globalization that included an increase in the spread of forms of mass

21

Walsh-Russo

media, according to Thorn, borders of nation-states and national identities also became

increasingly fluid and porous.

Conditions of contemporary globalization, or "internationalization" as Tarrow argues

(Tarrow, 2005), impact how transnational movements shift, change, and spread tactics and

ideas from one setting to another. In evaluating forms of diffusion and its consequences

for a movement, Tarrow and McAdam (2006) conceptualize relational diffusion is a form of

diffusion through which information diffuses from one site to another through familiar ties,

given that activists most likely distribute information with activists they already know than

with less familiar colleagues. As a result, relational diffusion as a component of

transnational movement dynamism carries with it far less transformative potential for a

given movement, since activists are within familiar networks where expectations are clear.

A plethora of factors either stymie or facilitate the transnational diffusion of tactics. These

include internal characteristics of movements themselves, the transnational linksbetween different national movements, and the characteristics of national political

contexts. All of these factors can influence adaptation of new tactics, the transformation

of movement goals and identities, and the process of "creative reinterpretation." In general,

the statements generated from previous, aforementioned studies focus in on the

characteristics and quality of social ties necessary for the spread of tactics. However, in

addition to these questions, further investigation is needed to determine the impact of the

broader political and historical context, particularly the impact of limited or open state

receptivity on the social ties that help facilitate transnational diffusion. That is, 1) the active

22

Walsh-Russo

work movement participants must conduct in order for a sense or notion if collective

identification with a movement to take place, including the recognition that actors share

similar political contexts and struggle between movement sites helps initially spread tactics 2)

and the subsequent reception by domestic states impacts whether or not tactics may be used

or additional, contingent tactical innovation developed. The recent events throughout the

mid-East, Russia and the United States demonstrate the spread of tactics, ideas and strategies

across geographic expanse. Previous empirical studies on transnational movements highlight

how transnational movements as a form of social movement organizing are dynamic sites of

struggle and contestation. I argue further analysis is needed in order to reveal the dynamism

of the struggle within and between transnational movements as connected sites of action.

Furthermore, within the continually shifting transnational space beyond or above state

borders, at least part of the internal work conducted surrounds the choice of tactics,

frequently adapted from external or outside actors, to be used or discarded. Thus,

participants donot passively accept or receive diffused items. Processes of adoption and

adaptation are most often negotiated and contested among actors. As Chabot and Duyvendak

discuss, diffusion across transnational movements involves not only top down, but also

bottom- up adoption, with a reformulation of tactics and strategies by adopters as well as

transmitters (Chabot and Duyvendak 2002: 728). Transnational social movement participants

and their organizations work to challenge cultural practices as well as enact institutional,

structural change {Whittier and Meyer, 1994; Cohen and Arato, 1992). Given the cultural and

structural challenges of such movements to multiple sites of focus, action, and audiences,

elements of a past movement's uniqueness frequently carry over to other movements.

23

Walsh-Russo

Thus, influenced by a preceding, connected movement's knowledge of useful tactics,

movement participants adapt particular organizational strategies, recruitment tactics, and

ideological beliefs from previous movements, and reformulate these tactics among an

array of options.

III.

Case Selection: What is Occupy? How did it spread? (3pgs).

a. Anti-Fracking: a timeline and review

b. Josh Fox’s Gasland

c. President Obama and Republican candidate Mitt Romney offer public support

for expansion of natural gas extraction.

IV.

Findings:

a. Borrowed Items:

b. Occupy ‘Well’ St. as direct action campaign against fracking.

c. “Global Day of Action” known as “Global Frackdown”

Wood writes “ Global days of action are a growing form of transnational contention (p71).”

“Events may include:

Human signs spelling out “Ban Fracking” targeting decision-makers

Protests or street theater outside oil or gas company headquarters or elected officials’ offices

Frackdown mock wrestling event where community members take on oil/gas executives

and/or elected officials

Erect and take down fake drilling rig in park or public square and put up wind turbine

Film screenings of Gasland or Split Estate

Petition gathering actions

Visibility events at key intersections with signs

Assemblies/pot lucks about fracking with community members”

24

Walsh-Russo

“Hydro fracking” or what is otherwise known as “fracking” beneath the earth’s surface is

process What is the topic? What are the concerns within anti-fracking? What’s at stake? What

are its connections to the Occupy movement? More broadly, what is the role of space within

diffusion processes? (3-5pgs).

V.

Discussion and Conclusion:

a. Further research? What can this case study tell us about rural to urban

movement tactics? Does space matter in contention? If so, how?

25

Walsh-Russo