PPTX

advertisement

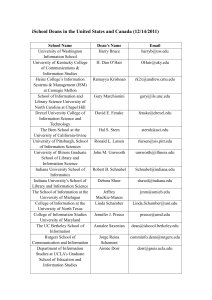

Musical Prosody Strategies of Performance Revealed in Graphs Elaine Chew ELE021 / ELED021 / ELEM021 6 Feb 2012 Logistics • 2-3 papers/presentations per week – two volunteers for afternoon of Mon, 27 Feb, 2012 • Exam questions will be drawn from readings/presentations and assignments • Module material posted publicly at www.eecs.qmul.ac.uk/~eniale/teaching/elem021 Prosody (Palmer & Hutchins) • In Speech: Variations in frequency, amplitude, duration that form grouping, prominence, and intonation • In Music: Variations in frequency, time, amplitude, and timbre to create expression to – Communicate emotion (Juslin & Sloboda 2001) – Clarify structure (Kendall & Carterette 1990) • Indicated by composer in score (Lerdahl & Jackendoff 1983) • Indicated by performer in interpretation (Apel 1972) Prosody in Speech • Acoustic variation in fundamental frequency, spectral information, amplitude, and relative durations of speech. • Can be explained by cognitive structures implicit in minds of speakers (Pierrehumbert 1999) • Word level: disambiguating bet competing words – E.g. greenhouse vs. green house • Above word level: syntax/semantics/discourse structure – E.g. Illocutionary intent: statement or request • Most definitions distinguish between pitch and other (e.g. time) dimensions Prosody in Music • Relatively fixed in terms of mostly pitch, and also duration, categories: discussion focuses on rhythm, grouping, prominence • Musical meter ~ linguistic stress – Syllable timed vs. stress timed languages • Difference: degree of isynchrony or temporal regularity Kreisler Plays Kreisler Function of Music Prosody • Segmentation: segmenting continuous audio stream into component units • Focus and Prominence: highlighting items of relative importance • Coordination: such as turn taking • Emotional response: attributing emotional states 13 25 1 37 85 133 49 97 61 109 145 73 121 157 169 Comparing performances Daniel Barenboim Feb 02, 1987 ℗ 1987 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH Hamburg Maurizio Pollini ℗ 1992 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH Hamburg Artur Schnabel ℗ 2009 EMI Records Ltd. Segmentation • Phrase boundaries marked by changes in intensity, tone duration, and articulation • Phrase boundaries indicated by – Phrase-final lengthening – Decreased amplitude (Drake & Palmer 93, Palmer 96) • Hierarchy: – Amount of slowing corresponding to depth of embedding (Todd 85/89, Shaffer & Todd 87) www.sonicvisualiser.org Beat Annotation of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata performed by Artur Schnabel first note of each bar Comparisons of the three performances (b) Pollini starts each phrase at the beginning of each bar (each phrase marked by an accel-decel arc) (a) Barenboim starts phrases at beginning of bars with a few exceptions accelerate across barline (c) Schnabel decelerate across barline accelerate across barline almost never aligns phrase starts with barline as if always negating the barline “This is the tension between metric groups (measured, regularly recurring beat groupings) shown by the bar lines in the score, and the boundaries of figural groupings or gestures (‘temporal gestalts’) which are not generally shown in an unedited score. Thus, on one hand, performers must find the figural or phrasing groups hidden in the score and on the other, intuitively musical players must learn to overcome the seductive appearance of the bar lines which do not represent their natural feel for the gestural grouping of music.” (p.94, Bamberger 2011) “This is the tension between metric groups (measured, regularly recurring beat groupings) shown by the bar lines in the score, and the boundaries of figural groupings or gestures (‘temporal gestalts’) which are not generally shown in an unedited score. Thus, on one hand, performers must find the figural or phrasing groups hidden in the score and on the other, intuitively musical players must learn to overcome the seductive appearance of the bar lines which do not represent their natural feel for the gestural grouping of music.” (p.94, Bamberger 2011) Prominence • Using stress/accent to signal focus or more significant events • Devices: – Louder or change articulation (e.g. staccato) to mark metrically important (Sloboda 1983, 1985) – Louder, longer, more legato (Gabrielsson 1974) – Vibrato (Seashore 1938, Small 1937) – Exaggerating intervals Comparing performances Daniel Barenboim Feb 02, 1987 ℗ 1987 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH Hamburg Maurizio Pollini ℗ 1992 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH Hamburg Artur Schnabel ℗ 2009 EMI Records Ltd. 13 25 1 37 85 133 49 97 dotted rhythm 61 dotted rhythm 109 145 dotted rhythm 73 121 157 169 dotted rhythm Entrance of the RH melody 13 25 1 37 85 133 bass line 49 97 61 109 145 73 121 157 169 Schnabel: bass line bass line onsets only lands on the beat here listen Schnabel: large scale gestures 13 listen 25 1 37 85 133 49 97 61 109 145 73 121 157 169 “the thing that stands out in the Schnabel performance is his almost mysterious ability to create or to project a 'long line' when the piece is basically slow-moving to static.What I mean by 'mysterious' is that trying to account for how that whole first phrase (even though only 4 bars long) is as if in one long breath. The other performers seem to stop at each bass note, with the right hand just embellishing it, but not make it move, even in its stasis. But if you try to listen for particular aspects–dynamics, rubato, balance–I, at least, can't say what he does to make that long breath happen. As he used to say, if you can HEAR it, you can make it happen. It's a kind of concentration, never letting the bass line (which couldn't be more banal–a sort of ordinary 'walking bass') stop.” - Bamberger “the thing that stands out in the Schnabel performance is his almost mysterious ability to create or to project a long line when the piece is basically slow-moving to static. What I mean by 'mysterious' is that trying to account for how that whole first phrase (even though only 4 bars long) is as if in one long breath. The other performers seem to stop at each bass note, with the right hand just embellishing it, but not make it move, even in its stasis. But if you try to listen for particular aspects–dynamics, rubato, balance–I, at least, can't say what he does to make that long breath happen. As he used to say, if you can HEAR it, you can make it happen. It's a kind of concentration, never letting the bass line (which couldn't be more banal–a sort of ordinary 'walking bass') stop.” - Bamberger Schnabel: large scale gestures Schnabel: large scale gestures Coordination • Regulate turn-taking and coordination • Coordination – in speech through intonation patterns and pauses – in music through rate priming (tempo persistence) • Turn-taking – in improvised music, elaboration upon previously heard ideas (Johnson-Laird 1991, Pressing 1988) Emotional Response • Prosodic features conveyed emotion in addition to structural features (mode) • Most successful emotions (Gabrielsson & Juslin 1996, Krumhansl 1997, Juslin 2001): – Sad: slow tempo, low sound level, legato – Happy: fast tempo, high sound level, staccato Assignment 1 1. Bring two versions of a piece of music that has variations in tempo or loudness to share with the class. Assignment 1 2. Download and install Sonic Visualiser. Select a 30-60 second segment of music containing tempo variations. Annotate the beat onsets for this same segment in your two audio examples using SonicVisualiser. 3. Plot the Beat onsets on a timeline using Excel or Matlab. Assignment 1 4. Plot the Tempo at each Beat as: • a reciprocal of the inter-beat onset-interval • a moving average over a window of three beats • a moving average over a window of five beats • another function of the beats data you generated, specifying clearly the function that you used Office Hours • Elaine Chew (ENG 2.12) – Tue 3pm-4pm and by appointment • Dimitrios Giannoulis – Wed 1pm-3pm Reference Palmer, C., & Hutchins, S. (2006). What is musical prosody? In B. H. Ross (Ed.), Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 46: 245278. Chew, E. (to appear). About Time: Strategies of Performance Revealed in Graphs. Visions of Research in Music Education Special Issue in honor of Jeanne Bamberger, ISSN 1938-2065. Coming Soon … Gerhard Widmer Werner Goebl Simon Dixon 2002, 2008