Demystifying Economics: Macroeconomic Policy

advertisement

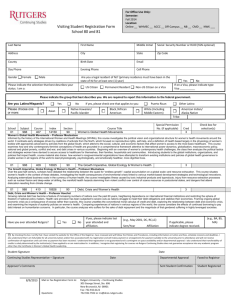

September 24, 2012 Radhika Balakrishnan, Center for Women’s Global Leadership, Rutgers University James Heintz, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Introduction Economic and Social Rights Fiscal Policy and Human Rights Feminist Analysis • Creates strong policy arguments, which can more effectively inform the formulation of legislation, regulations, and budgets to address human rights. • Committed to sustainable change by focusing on process, rule of law, and the democratic functioning of society. • Standards that allow all people to live with dignity, freedom, equality, justice, peace. • Set of principles that apply to universal, inalienable, interconnected, indivisible, non-discriminatory. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 Food Work Health Housing Water and sanitation Adequate standard of living Requirement for progressive realization Use of maximum available resources Avoidance of retrogression Non-discrimination and equality Participation, transparency and accountability • The obligation of conduct requires action reasonably calculated to realize the enjoyment of a particular right. – Ex. Expenditures on health • The obligation of result requires States to achieve specific targets to satisfy a detailed substantive standard. – Ex. Health outcomes Fiscal Policy • Government Expenditure • Government Revenue Monetary Policy C+I+G+X-M [consumption + investment + government spending + (exports-imports)] • The use of government expenditure and revenue collection to influence the economy. • Deficit – Excess of spending over revenues in a given period. • Debt – A deficit in one period adds to accumulated debt that period; a surplus reduces debt. • Spending – Government spending two types – current spending and investment. • Investment – Usually creates a long-term capability and gives a return in terms of greater income or lower costs. • Government revenues – Taxes, fees, royalties from minerals, operating surpluses from government enterprises. • Government borrowing –Bonds sold by governments to financial institutions usually in your own currency; loans are frequently in foreign currency from World Bank, regional development banks, and commercial banks. 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 Argentina 1994 1995 Brasil 1996 1997 Chile 1998 1999 2000 Costa Rica 2001 2002 Cuba 2003 2004 2005 México Source: Balakrishnan and Elson (2011), Economic Policy and Human Rights, Figure 3.4 • Conduct does not always yield results therefore we need to look at both. • Guyana: Health spending per person grew from from $79 in 1995 to $189 in 2010 (expressed in the value of the dollar in 2005). • South Africa: Spending increased from $425 to $935 (in $2005). • Maternal mortality rates INCREASED: – In Guyana from 170 to 280 (per 100,000 live births) – In South Africa from 260 to 300 (per 100,000 live births) • Governments receive revenue from many sources including, taxation, royalties paid for utilization of natural resources, and profits from public enterprises. • We focus on taxation as this is typically the most important way in which governments mobilize domestic resources. Source: Balakrishnan and Elson (2011), Economic Policy and Human Rights, Figure 6.1 1.8 1.6 % GDP 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 Corporative Individuals Source: Balakrishnan and Elson (2011), Economic Policy and Human Rights, Figure 5.16 • Gender equality and tax policy can be examined from several perspectives. – Explicit and implicit bias. • CEDAW requires that families be based on ‘principles of equity, justice and individual fulfillment for each member’ (General Recommendation 21, para. 4). – It implies that women be treated as equal to men in tax laws: as individual, autonomous citizens, rather than as dependents of men. • Deficit: difference between current government spending on goods and services and total current revenue. – When a government runs a deficit, it must borrow to make up the difference. • Debt: the total amount of borrowing by the government. – Forms of debt: government bonds, external debt • The public debt is very important in terms of its effect on realization of social and economic rights • But the relationship is complex – Can protect rights during economic downturns – But high levels of debt may compromise future rights • Many factors influence the sustainability of debt – – – – Domestic policy, exchange rates, interest rates International policies Power dynamics in the global economy Not all countries face the same constraints • Who benefits from high debt servicing payments? – The owners of the debt (the people who own bonds or the external debt) – Represents an outflow of resources • Global inequalities – Some countries can borrow on more favorable terms than others. – Example: U.S. and U.K. have growing levels of debt but low debt servicing costs. • Bond markets and financiers – Borrowing can give financial interests power over domestic policy. • Reform needed at the global level • The debate: is government spending sustainable in a crisis? – United States of America: Stimulus of $757 billion. Example: job creation, but this part was gender biased. Also, about 1/3 was tax cuts. – China: $586 billion. Including, housing, rural infrastructure, transportation, health and education. – Greece: no stimulus. Austerity in the face of crisis. Massive cutbacks to government spending. • Utilize international human rights mechanisms such as the Universal Periodic Review, CEDAW, CESCR, CERD, etc. • Review your government’s human rights obligations. • Monitor local and national budgets, and find out if your country conducts gender budgeting. • Find out the size of your country’s debt and how is it constraining/facilitating human rights. • Learn more about what the IMF is doing in your country. Nexus: Shaping Feminist Visions in the 21st Century http://cwgl.rutgers.edu/resources/publications/economic-a-social-rights/nexus Rethinking Macro Economic Strategies from a Human Rights Perspective: Why MES with Human Rights II http://cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/publications/whymes2.pdf Auditing Economic Policy in the Light of Obligations on Economic and Social Rights http://cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/publications/auditing.pdf Macroeconomics and the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation http://cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/publications/Rights%20to%20Water%20and%20Sanitation.pdf Maximum Available Resources & Human Rights http://www.cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/publications/marreport.pdf The Right to Food, Gender Equality and Economic Policy http://cwgl.rutgers.edu/globalcenter/publications/Right%20to%20Food.pdf Email: cwgl@rci.rutgers.edu Website: www.cwgl.rutgers.edu , http://www.peri.umass.edu/ Facebook: Center for Women's Global Leadership Twitter: https://twitter.com/CWGL_Rutgers Tumblr: http://cwgl.tumblr.com/