MOTION TO DECLARE ALABAMA CODE §§15-20-21 et seq, 15

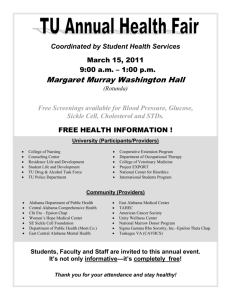

advertisement

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF LAUDERDALE COUNTY, ALABAMA STATE OF ALABAMA PLAINTIFF V. CASE NO. CC DEFENDANT MOTION TO DECLARE ALABAMA CODE §§15-20-21 et seq, 15-20-23 et seq., AND 15-20-26 et seq. UNCONSTITUTIONAL AND MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT The defendant moves to declare Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 15-20-26 et seq. unconstitutional on the following grounds: 1. On December 12, 1989, s, the defendant pled guilty to sex abuse in the 1st degree. On December 12, 1989, the Court adjudged the defendant guilty of said offense. On January 26, 1989, the Court sentenced the defendant to serve 6 months. On January 8, 1990, the Probation and Parole Officer filed a delinquency charge against Mr. Defendant because he failed to report to the Probation Officer as directed. On April 5, 2001, the Court discharged the defendant from probation. 2. On or about January 22, 2008 the Lauderdale County Sheriff’s Department arrested the defendant. The State of Alabama charged the defendant with establishing a prohibited residence and failing to register. 3. The March 2008 Lauderdale County Grand Jury indicted the defendant and charged him with violating Alabama Code §15-20-23 (failing to register within 30 days) and Alabama Code §15-20-26 (establishing a residence where a minor resides). Page 1 of 33 Motion 7 4. The defendant must now maintain 2 households. The defendant has been ostracized from the community. The defendant is unable to direct the upbringing of his child. The defendant is not allowed to live with his own biological son. The defendant has been forced to live with relatives. Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Declare Alabama Code §1520-20.1 et seqq. Unconstitutional I. History of Alabama Code §15-20-20.1 et seq. All states adopted sex offender registration laws because Congress passed the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violate Offender Registration Act, 42 U.S. C. §14071, which conditions certain federal law enforcement funding on the state’s adoption of sex offender registration laws. Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84, 89 (2003). The Act, however, does not require the registration laws to be applied retroactively. State v. Meyers, 923 P.2d 1024, 1029 (Kan. 1993). In 1967, Alabama enacted legislation requiring convicted sex offenders to register with law enforcement personnel after conviction. State v. C.M., 746 So.2d 401, 413 (Ala.Crim.App. 1999). In 1996, Alabama adopted the Community Notification Act known as Megan’s Law. C.M. at 413. In 1998, the Legislature amended the act to include juvenile adjudications. C.M. at 413. At that time, Alabama had the broadest community notifications laws of all states. C.M. at 413. On October 1, 2005 the Legislature amended Alabama’s convicted sex offender laws and implemented the most restrictive laws in the United States. Some of the most notable 2005 amendments include: Page 2 of 33 Motion 7 1. All violations of the Community Notification and Registration Act are Class C felonies except some violations involving juvenile defendants. Alabama Code §15-20-22(4)(d); §15-20-23(a); §15-20-24(d); §15-2025.1(d); §15-20-25.2(d); §15-20-25.3(g); §15-20-26(h); §15-20-26.1(g); §15-20-26.2(a); and §15-20-23.1. 2. Sex offenders are required to register their places of employment with local law enforcement. Alabama Code §15-20-22. 3. The Department of Public Safety bands a sex offender’s driver’s license and identification cards and the sex offender must have the card in his possession at all times. Alabama Code §15-20-26.2(a). 4. A sex offender must give 7 days prior notice to the Sheriff before beginning new employment or changing employment. Alabama Code §15-20-23.1. 5. A sex offender establishes a new residence when he is domiciled for 3 or more consecutive days. Before 2005, the offender established a new residence after 5 days. Alabama Code §15-20-23(b)(1). 6. Sex offenders establish a new residence any time they are released from custody even if it is the same location as before the conviction. Sex offenders also establish a new residence when granted probation even if the Judge never places the defendant in custody. Alabama Code §15-2023(b)(2) and §15-20-21(10). Page 3 of 33 Motion 7 7. A sex offender creates a new residence if the offender spends 10 or more aggregate days in a calendar month at a location. This provision did not exist before 2005. Alabama Code §15-20-23(b)(3). 8. A sex offender cannot stay in a hotel overnight if the hotel is within 2000 feet of a school or childcare facility. Sellers v. State, 935 So.2d 1207 (Ala.Crim.App. 2005); Alabama Code §15-20-26(a). 9. A convicted sex offender cannot live with his own minor child if his victim was under the age of 12. Alabama Code §15-20-26(c)(4). 10. The 2005 Amendments to Alabama Code §15-20-26(f) and §15-20-26(g). added the following provisions if the victim was under the age of 12. A sex offender is prohibited from: a. Loitering on or within 500 feet of any property on which there is a school, childcare facility, playground, park, athletic field, or any business or facility having a principal purpose of caring for, educating, or entertaining minors. Loiter means to enter or remain on property while having no legitimate purpose or remaining after that purpose is fulfilled. Alabama Code §15-20-26(f); and b. Accepting employment within the above described 500 foot areas. Alabama Code §15-20-26(g). II. The Alabama Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws violate the Ex Post Facto Clause because the laws punish the defendant retroactively. The Ex Post Facto Clause of Article I, §10(1) and Article I §9(3) of the Page 4 of 33 Motion 7 United States Constitution and Alabama Constitution Article I Section 7 and Section 22 prohibit a state from imposing retroactive punishment on those previously convicted of a crime. If the stated legislative intent of a statute was to enact a regulatory scheme that is civil and nonpunitive, then the Court must determine whether the statutory scheme is so punitive either in purpose or effect as to negate the State’s intention to enforce a civil restriction. Lee v. State, 895 So.2d 1038, 1041 (Ala.Crim.App. 2004). Apparently, if the legislature simply states they are trying to protect the public from harm, then the only issue is whether or not the statute is punitive in application. Lee at 1042. Kansas’ Community Notification Law, which is substantially similar to Alabama’s law, was found to violate the Ex Post Facto Clause. State v. Meyers, 923 P.2d 1024 (1996). The Meyers case involved an Ex Post Facto analysis because the registration statute allowed unlimited public access to any and all records contained in the registration file. The Court found this provision excessive and rose to the level of punishment thereby violating the Ex Post Facto Clause. Meyers at 1044. To determine if an act is punitive in its application, the Court must analyze the following factors: 1. Whether the sanction imposed by the act involves affirmative disability or restraint; 2. Whether, historically, the sanction has been viewed as punitive; 3. Whether a finding of scienter (mental state finding) was necessary before the act is applied; 4. Whether the act promotes retribution and deterrence; 5. Whether the behavior to which it applies was already criminal; Page 5 of 33 Motion 7 6. Whether the act has any alternate remedial purposes; and 7. Whether the scope of the act is excessive in relation to its purpose. C.M. at 417 citing Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. at 168-169. The Kansas Supreme Court, in State v. Meyers, reviewing a Community Notification Act substantially similar to Alabama’s held the act was unconstitutional, because as applied, its scope was excessive and disclosure of sex offender registration information was unrestricted. State v. C.M., 746 So.2d 401, 419 (Ala.Crim.App.1999). C.M. at 419 citing State v. Meyers, 923 P.2d 1024, 1043 (1996). The Court held the legislative aim in the disclosure provision was not to punish and that retribution was not an intended purpose. The Court ruled the repercussions, despite how they may be justified, however, were great enough under the facts to be considered punishment. Meyers at 1043. The unrestricted public access given to the sex offender registry is excessive and goes beyond that necessary to promote public safety. Because the Registration Act provisions make more burdensome the punishment for a crime after its commission, the statute violated the prohibition against Ex Post Facto laws. Meyers at 1043. In Lee, the State accused the defendant of establishing a residence within 2000 feet of a childcare facility in violation of Alabama Code §15-20-26(a). Lee v. State, 895 So.2d 1038, 1039 (Ala.Crim.App. 2004). The defendant pled guilty to violating the Community Notification Acts’ residency restrictions. Lee at 1038. Before pleading guilty, the defendant filed a motion to dismiss challenging the constitutionality of the statute. Id. at 1039. The Trial Court denied the motion by a written order but the Trial Court’s order only addressed the Ex Post Facto argument. Id. at 1039. Page 6 of 33 Motion 7 The defendant appealed the constitutionality of the Community Notification Act. Id. at 1039. The Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the constitutionality of the statute. Id. at 1038. On appeal, the defendant argued the Community Notification Act’s residency requirements were unconstitutional because: 1. Application of the Community Notification Act violated the Ex Post Facto Clause of the United States Constitution; 2. The Community Notification Act violated his Due Process Rights; and 3. The Community Notification Act violated his Substantive Due Process Rights. The Trial Court failed to address the Due Process arguments in the order denying the motion to dismiss, therefore, the Court of Criminal Appeals only considered the Ex Post Facto issue. Id. at 1039. In Lee, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals ignored the first and second Ex Post Facto factors because the defendant failed to present evidence he was banished or rendered homeless by the application of the statute holding “we cannot say that the residency requirements of the Community Notification Act operate to establish a regulatory scheme that has been considered punitive.” Lee at 1043. The record in this case contains no evidence that the act has led to substantial housing disadvantages for former sex offenders that would not have otherwise occurred through the use of routine background checks by landlords. Lee at 1043; citing Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84, 100 (2003). Page 7 of 33 Motion 7 The defendant failed to allege any facts to support his claim that the residency requirements of the Community Notification Act were punitive rather than civil. Lee at 1041. The defendant neither alleged facts to establish the statute was punitive as applied to him nor alleged facts to establish the statute was punitive on its face. Lee at 1041. The defendant conceded the residency restrictions of the Community Notification Act had a rational, non-punitive purpose but argued the restrictions were excessive to accomplish that purpose. The Court of Criminal Appeals ignored this issue again stating the defendant failed to allege any facts to support this contention. Lee at 1043-1044. The Court stated that nothing in the record before them indicated the regulatory scheme of the residency restrictions of the Community Notification Act was anything other than reasonable in light of the non-punitive objective of keeping children safe from convicted sex offenders. Lee at 1044. The Court affirmed the Trial Court’s denial of the motion to dismiss holding the defendant failed to show by the clearest proof the effects of the residency restrictions of the Community Notification Act negate the legislature’s intention to protect the public, in particular children, from convicted sex offenders. Lee at 1044. The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals relied on the United States Supreme Court Case of Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003) which upheld the constitutionality of the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act. The Court of Criminal Appeals, however, noted the significant differences between Alabama’s Community Notification Act and Alaska’s. Lee at 1041. The United States Supreme Court case of Smith v. Doe challenged Alaska’s Sex Offender Registration Act. Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003). The sex offenders filed a Page 8 of 33 Motion 7 §1983 action challenging the constitutionality of Alaska’s Sex Offender Registration Act. Smith v. Doe, at 84. The sex offenders alleged the act violated the Ex Post Facto Clause. Both parties moved for summary judgment. The United States District Court for the District of Alaska ruled in favor of the State. The sex offenders appealed. The Court of Appeals reversed and remanded the case. The Alaska Supreme Court ruled the act was non-punitive and its retroactive application did not violate the Ex Post Facto Clause. The United States Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case. Smith at 84. Under the Alaska registration statute, if the offender was convicted of one nonaggravated sex crime, the offender was required to provide annual verification for 15 years. If the sex offense was aggravated or the offender was convicted of 2 or more offenses then the offender was required to register for life and verify his registration information quarterly. Smith at 84. The Alaska statute required the Trial Court to inform the defendant of the Registration Act requirements. Smith at 86. The Alaska statute does not impose any disability or restraint. Smith at 86. Therefore, the Alaska statute does not resemble imprisonment. Smith at 86. The record in Smith contained no evidence the act led to substantial occupational or housing disadvantages for sex offenders that would not have otherwise occurred. Smith at 86. The Alaska sex offender residency updates were not required to be made in person. Smith at 86-87. Alaska sex offenders were free to live and work with no supervision or restrictions. Smith at 87. The Smith v. Doe case of Alaska only addressed constitutionality of the registration requirements. The Alaska convicted sex offender statue only contains a registration requirement. Smith at 90. The Alaska statute does not restrict residency. Page 9 of 33 Motion 7 Smith at 90-91. This case did not address the living restrictions which are at issue in Mr. Defendant’ case. Smith at 89. The location of the act in the criminal code is relevant to determining whether the statute is intended to be civil or punitive in nature. Smith at 94. In Alabama, part of the sex offender laws are contained in the criminal code and part are contained in Title 15. By requiring the defendant to live separate and apart from his family, the Alabama Sex offender laws are akin to placing the defendant in prison or work release. Placing the defendant in work release prevents the defendant from living with his family. The Alabama statutes effectively place the defendant in confinement and its effect, whether intended or not, is punitive and restrains liberty. The effects of the Alabama statutes, as currently enacted, closely resemble colonial punishments. Historically offenders were required to stand in public with signs detailing their offenses. Smith at 97. Some murderers were branded with an “M” and a thief with a “T”. Smith at 98. The goal of such punishments was to make these offenders suffer permanent stigmas which in effect cast the person out of the community. Smith at 98. The most serious offenders were banished after which they could neither return to their original community nor, because of their tarnished reputation, be admitted easily into a new one. Smith at 98. Often times historically an offender was expelled from the community. Smith at 98. Contrary to Alabama’s statute, the Alaska’s statute did not make the publicity and the resulting stigma an integral part of the regulatory scheme objective. Smith at 99. The Alabama statute, however, does make the stigma and banishment an integral part of the regulatory scheme by preventing the defendant from living with his own family and Page 10 of 33 Motion 7 listing the offender’s sex offense conviction on the offender’s driver’s license. Alabama Code §§15-20-26(c)(4) and 15-20-26.2(a). Alabama allows unlimited access to registration information. Alabama also brands a person by placing the sex offense conviction on the offenders’ drivers’ license. Alabama Code §15-20-26.2(a). Alaska’s sex offender statute is drastically different from Alabama’s sex offender statutes. Nearly every factor in Alaska’s statute the United States Supreme Court used to illustrate its non-punitive nature is contrary to Alabama’s statutes. Alabama’s statutes severely restrict residency and employment, effectively banishing the indigent sex offender from the community. These restrictions resemble traditional forms of punishment. Therefore, Alabama’s laws effectuate a traditional form of punishment. The notification flyers amount to public shaming. Alabama’s community notification and residency restrictions, contrary to Alaska’s statutes, place affirmative disabilities and restraints on where a sex offender can live and work. Under the Alaska statute, the offender can live and work anywhere. Alabama statutes apply equally to all sex offenders regardless of risk or danger of recidivism. If the disability or restraint on freedom is minor and indirect, its effects are unlikely to be punitive. Smith at 100. The Alaska Act imposed no physical restraint. Smith at 100. The Alabama statute, however, does place a physical restraint which is similar to being in the work release center by preventing the defendant from living with his own biological child. Alabama Code §15-20-26(c)(1-4). The Alaska statute allowed the offenders to freely change jobs or residencies. Smith at 100. The Alabama statute prevents an offender from changing employment Page 11 of 33 Motion 7 without first giving 7 days notice. The offender is further precluded from all employment which involves children which may bring the offender in contact with children. Alabama Code §15-20-26(a) and Alabama Code §15-20-23.1. An Alabama sex offender must give 30 days prior notice before changing residency. Alabama Code §15-20-23. The record in the Smith case was void of any evidence the Registration Act led to housing disadvantages for sex offenders. Smith at 100. The United States Supreme Court in Smith rejected arguments the Alaska Act was similar to probation or supervised release in terms of restraint imposed because the Alaska statute allowed sex offenders to freely move where they wish and to live and work as other citizens with no supervision. Smith at 100. The Alaska offender did not need permission from the sheriff before they could change employment as required under the Alabama statute. III. The Alabama Sex Offender laws are excessive in relationship to the legislative purpose. With regard to the excessiveness of Alaska’s statute in relation to its purpose, the Court reasoned that merely requiring registration and dissemination of information to the public was not excessive. Smith 104-105. The Alabama statute, on the other hand, goes beyond mere registration and notification. The statue places great physical restraints and imposes the most serious sanction of precluding an offender from living with his own biological child retroactively. Alabama Code §15-20-26(c). If the act prohibits an offender from living with his biological family, when the alleged victim is not his own children, the act should not have retroactive application. If this consequence is a valid and appropriate restriction, it should not be applied retroactively. Page 12 of 33 Motion 7 Application of the Alabama Registration Act differs from a civil remedy in 3 very important aspects 1. The sanctions constitute a severe deprivation of the offender’s liberty; 2. The sanctions are imposed on everyone who has been convicted of a sex offense; and 3. The sanctions are imposed only on sex offenders. Smith at 112 (Justice Stevens dissenting but concurring in the judgment). In Smith, the Supreme Court distinguished between Alaska’s sex offender registry and colonial punishments such as shaming, branding, and banishment. The Court held the registry in Alaska merely involved dissemination of information where as the colonial punishments either held the person up before his fellow citizens for face to face shaming or expelled him from the community. Smith, 538 U.S. at 98. Banishment has always been a form or traditional punishment historically. Colonial punishments were designed to make offenders suffer permanent stigmas which in effect cast the person out of the community. The residency restrictions of the Alabama law create a permanent stigma as well as effectively cast the person out of the community. The Smith Court also described as banishment situations in which individuals could neither return to their original community nor, reputation tarnished, be admitted easily into a new one. Preventing offenders from making a home in many communities after they have served their sentence substantially resembles banishment. Page 13 of 33 Motion 7 The Alabama residency restrictions also serve a traditional aim of punishment, that being deterrence. One reason we put offenders in prison is to reduce the likelihood of future crimes by depriving the offender of the opportunity to commit the crime. This is precisely what Alabama’s Community Notification and Residency Restrictions statutes are intended to do. Therefore, they resembled the traditional aims of punishment. The Alaska statute allows the sex offender to move or leave once notified of a violation without being guilty of a crime. Smith, 538 U.S. at 100. The Alabama statute limits the housing choices of all offenders, regardless of their type of crime, type of victim, or risk of re-offending. Alabama Code §15-20-26. This leaves offenders to live in a small area with no appropriate housing or jobs. It also eliminates many employment opportunities. In this respect, the statute is not narrowly tailored and its restrictions are excessive and unconstitutional. When a defendant enters into a plea and is advised of his rights, he is asked if he understands the possible punishment and the terms and conditions of his plea. Alabama Rules of Criminal Procedure 14.4(a)(1)(i)-(viii); 14.4(2); 14.4(3); 14.4(b); 14.4(c); 14.4(d); and 14.4(e). The defendant cannot make a knowing and intelligent plea of guilt because a convicted sex offender never knows what the possible consequences of pleading guilty will be. Pursuant to the current interpretation of the law, a defendant can never know with any certainty what the consequences of his plea will be because the legislature can amend the law and impose restrictions which did not exist when the defendant entered his plea. This law is punitive because Alabama’s sex offender laws require branding an offender by placing a defendant’s criminal conviction on the convicted person’s driver’s Page 14 of 33 Motion 7 license. Although driver’s license information is otherwise a public record, the sex offense conviction advertised and revealed every time a person is required to display his drivers’ license for whatever reason. IV. Alabama’s Sex Offender laws unconstitutionally impinge upon the right to travel and freely associate. Under the current application of the Community Notification Act, a Lauderdale County resident convicted sex offender can barely live within the city limits of Florence. Very few areas in the county qualify and meet the criteria of the residency restriction of Alabama’s sex offender laws. The convicted sex offender is essentially precluded from working in Lauderdale County. The defendant can barely live in Lauderdale County under the current status of the law. Alabama Code §15-20-26(c)(4) residency restrictions preclude Mr. Defendant from living with his own biological child because Mr. Defendant’ alleged victim was under the age of 12. Mr. Defendant cannot afford to pay for 2 households. At the time Mr. Defendant entered into the marriage relationship and had a child, he could legally live with his child and assumed he would only be required to pay for 1 household. Retroactive application of this law requires Mr. Defendant to financially support 2 households and live separately and apart from his biological child which is a direct violation of his Liberty Interest guaranteed by the 5th and 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution and the Alabama State Constitution Article I, §6 (1901); and the right to Freely Assemble in violation of United States Constitution Amendments 1 and 14. The right to Travel protects a person’s right to enter and leave another state, the right to be treated fairly when temporarily present in another state, and the right to be Page 15 of 33 Motion 7 treated the same as other citizens of that state when moving there permanently. Moore at 1348. A sex offender establishes a new residence when he is domiciled for 3 or more consecutive days. Alabama Code §15-20-23(b)(1). Domiciled, however, is not defined by Title 15. A sex offender creates a new residence if the offender spends or more aggregate days in a calendar month at a location. Alabama Code §15-20-23(b)(3). Therefore, an Alabama sex offender essentially is precluded from spending 10 or more days on vacation without first complying with all change of residence requirements, notices, community notification flyers, etc. and arguably 3 days pursuant to Alabama Code §15-20-23-(b). The sex offender cannot stay in a hotel if the hotel is within 2,000 feet of a school or childcare facility. Alabama Code §15-20-26(a). The defendant must contact the Sheriff to determine if he can spend a night in a hotel. Furthermore, even if the sex offender complies with all of the notification and notice requirements of the Code, the sex offender cannot stay in the same hotel room with his child if he is categorized as Mr. Defendant. V. The Alabama Sex Offender laws are unconstitutionally vague. The Due Process Clause pursuant to United States Constitution Amendments 5 and 14 and Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901) has led to the judicial doctrine of vagueness, which requires a criminal statute to define the criminal offense with sufficient definiteness to allow ordinary people to understand what conduct is prohibited and in a manner that does not encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement. Doe v. Miller, 405 F.3d 700, 708 (8th Cir. 2005). Page 16 of 33 Motion 7 A convicted sex offender has no way of knowing whether or not spending the night in a hotel would violate the Alabama Sex Offender laws. Before a defendant can spend a night in a hotel, he is required to contact the Sheriff’s Department and be sure he or she is not violating the Community Notification Act. Sellers v. State, 935 So.2d 1207 (Ala.Crim.App. 2005). Under the current interpretation of the law, a defendant could not take a vacation of more than 10 days without violating the Community Notification Act. Sellers v. State, 935 So.2d 1207 (Ala.Crim.App. 2005). Pursuant to Alabama Code §15-20-23(b) an adult sex offender establishes a new residence in any of the following circumstances: 1. Whenever adult criminal sex offender is domiciled for 3 consecutive days or more; 2. Whenever the adult sex offender is domiciled following his or her release regardless of whether that sex offender has been domiciled at the same location prior to the time of conviction; and 3. Whenever an adult criminal sex offender spends 10 or more aggregate days at a location during a calendar month. The statute is unconstitutionally vague. For example, under the current status of the Community Notification Act, a person cannot be hospitalized in Lauderdale County for more than 3 or possibly 10 days without violating the Community Notification Act. The Act contains no provision which allows for a waiver of any violation. Therefore, if Mr. Defendant is hospitalized for 10 days or more, because the hospital is too close to a day care facility, he is in violation of the Community Notification Act. Alabama Code §15-20-23(b)(1). Page 17 of 33 Motion 7 If an offender spends 10 or more aggregate “days” in one place, the offender establishes a new residence. The statute, however, fails to define the term day. Is a day 24 hours, 12 hours, or 8 hours? Alabama Code §15-20-23(b). Under the current law, every sex offender who is housed in the Lauderdale County jail for more than 10 days has committed another felony because they are in violation of the Community Notification Act. The statute makes no exceptions for being jailed or hospitalized. Under the most recent Alabama case, being jailed or hospitalized is a living arrangement which is of no choice of the defendant. Such living arrangement, however, directly violates Alabama Code §15-20-23(b). Sellers v. State, 935 So.2d 1207 (Ala.Crim.App. 2005). In Moore, a group of Florida sex offenders filed a class action challenging the constitutionality of Florida’s sex offender registration/notification statute. Doe v. Moore, 410 F.3d 1337 (11th Cir. 2005). The United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida granted the State’s motion to dismiss. The plaintiffs appealed. Id. at 1337. The Florida statute, however, differs in many respects from the current Alabama statute. The following differences are most obvious: 1. A Florida sex offender may be relieved of his or her registration obligation if he or she is pardoned or petitions a Court 20 years after being released from custody or supervision and, among other things, the Court finds the sex offender is not a potential threat to public safety. Moore at 1341; 2. Other felons are also subject to registration, not just sex offenders; and Page 18 of 33 Motion 7 3. The Florida Statute did not apply retroactively; the statute exempted sex offenders released from supervision before enactment of the statute. Moore at 1348. The plaintiffs claimed the acts: 1. Violated Substantive Due Process by infringing their liberty interest and good reputation, their Right to Travel, Privacy, Employment, and Freedom of Religious Association; 2. Were unconstitutional on Equal Protection grounds because the law imposed post-release reporting burdens more restrictive than other convicted felons; 3. Violated the Separation of Powers Doctrine because the sex offender laws nullified judicial sentencing; and 4. Were an unconstitutional impairment of contract because they altered plea bargains made by sex offenders who were sentenced prior to their enactment. Moore at 1341. VI. The Alabama Sex Offender laws violate the Equal Protection Clause because the notification and residency restrictions apply to sex offenders but not felons convicted of other crimes. Equal Protection claims are reviewed under 1 of 3 levels of review. The level of review depends on the parties involved and the right affected by the law. State v. C.M., 746 So.2d 401, 414 (Ala.Crim.App. 1999). If the law affects a fundamental right or a suspect class a reviewing court applies the strict scrutiny standard of review. Under a strict scrutiny review, the State must show a compelling state interest in enacting the law. C.M. at 414. Page 19 of 33 Motion 7 An intermediate level of review is applied if the law affects a protected economic interest or liberty. If the intermediate level of review is used, the test is whether the law is reasonably related to the stated objective. C.M. at 414. If the law does not employ a classification based on a race, sex, national origin, or legitimacy of birth and does not impinge upon a fundamental right, it is subject to review under the rational-relationship analysis. If the rational-relationship test is used, the law must be rationally related to the State’s objective. C.M. at 414. Interestingly, the stated policy for these statutes, among other things, is to provide certain discretion to Judges in applying these requirements. Alabama Code §15-20-20.1. The new amendments, however, have eliminated all discretion. The legislative findings regarding the Community Notification Act are codified in Alabama Code §15-20-20.1. According to the legislative findings, law enforcement agencies’ efforts to protect their communities, conduct investigations, and quickly apprehend criminal sex offenders are impaired by the lack of information about criminal sex offenders who live within their jurisdiction and that the lack of information shared with the public may result in the failure of the criminal justice system to identify, investigate, apprehend, and prosecute criminal sex offenders. Alabama Code §15-20-20.1. The above stated purpose applies to all crimes and all persons convicted of crimes. These concerns are not unique to sex offenders. No other convicted person is treated similarly to convicted sex offenders. All other people convicted of crimes pay their debt to society and are eventually released and allowed to live freely without further restrictions. If the legislative findings justify the Page 20 of 33 Motion 7 current treatment of convicted sex offenders, then the same argument can be made for all people convicted of any crime. In this way, the Alabama Sex Offender laws violate the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution Amendment 14 and Alabama State Constitution Article I, §1 and §6 (1901) by treating similarly situated individuals differently without justification. VII. The Alabama Sex Offender laws unconstitutionally restrict the fundamental right to enjoy a family relationship. When a State enacts legislation infringing fundamental rights, the Courts will review the law under a strict scrutiny test and uphold it only when it is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling State interest. Moore at 1343. The United States Supreme Court has recognized fundamental rights include those guaranteed by the Bill of Rights as well as certain Privacy interest implicit in the Due Process Clause and other Constitutional Rights. Moore at 1343. These special liberty interests include the rights to marry, to have children, to direct the education and upbringing of one’s children, to marital privacy, to contraception, to bodily integrity, and to abortion. Moore at 1433. To determine if a right is fundamental, the Court must determine whether the right and liberty is weighed objectively, deeply rooted in this nation’s history and tradition and implicit in the concept of ordered liberty such that neither liberty nor justice would exist if they were sacrificed. Moore at 1343. The family is the foundation upon which modern civilization is based. It is not surprising therefore, that courts have zealously protected the integrity of the family and the United States Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed the fundamental right of parents to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children. See, e.g., Page 21 of 33 Motion 7 Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 232, 92 S.Ct. 1526, 32 L.Ed.2d 15 (1972); Parham v. J.R., 442 U.S. 584, 602, 99 S.Ct. 2493, 61 L.Ed.2d 101 (1979); Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753, 102 S.Ct. 1388, 71 L.Ed.2d 599 (1982); Michael H. v. Gerald D., 491 U.S. 110, 123-24, 109 S.Ct. 2333, 105 L.Ed.2d 91 (1989). The 14th Amendment provides that no State shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without Due Process of law.” Courts have long recognized that the Amendment’s Due Process Clause, like its 5th Amendment counterpart, “guarantees more than Fair Process.” Washington v. Glucksberg, 531 U.S. 702, 719, 117 S.Ct. 2258 (1997). The Clause also includes a substantive component that “provides heightened protection against government interference with certain fundamental rights and liberty interests.” Id., at 720, 117 S.Ct. 2258; see also Reno v. Flores, 507 U.S. 292, 301-302, 113 S.Ct. 1439, 123 L.Ed.2d 1 (1993). Procedural Due Process guarantees a State will not deprive a person of life, liberty, or property without some form of notice and opportunity to be heard. Moore at 1342. The Due Process Clause of the 5th and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution and Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901) provides a heightened protection against government interference with certain fundamental rights and liberty interest such as child rearing decisions. Substantive Due Process protects fundamental rights so implicit in the concept of ordered liberty that neither liberty nor justice would exist if they were sacrificed. Moore at 1342-1343. Fundamental rights protected by Substantive Due Process are protected from certain State actions regardless of the procedures the State uses. Moore at 1343. Page 22 of 33 Motion 7 In Moore, the Court held that no fundamental rights protected by the United States Constitution had been affected by the Sex Offender Act, therefore, a rational basis test applied to the substantive Due Process and Equal Protection claims. Moore at 13411342. A statue is considered constitutional under the rational basis test when there is any reasonably conceivable set of facts that could provide a rational basis for it. Moore at 1346. The Liberty Interest at issue in this case, the interest of parents in the care, custody, and control of their children, is perhaps the oldest of the fundamental liberty interests recognized by this Court. More than 75 years ago, in Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399, 401 43 S.Ct. 625, 67 L.Ed. 1042 (1923), the United States Supreme Court held that the “liberty” protected by the Due Process Clause includes the right of parents to “establish a home and bring up children” and “to control the education of their own.” Two years later, in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 534-535, 45 S.Ct. 571, 69 L.Ed. 1070 (1925), the United States Supreme Court again held that the “liberty of parents and guardians” includes the right “to direct the upbringing and education of children under their control.” The United States Supreme Court explained in Pierce that the child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” Id., at 535, 45 S.Ct. 571. The United States Supreme Court returned to the subject in Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158, 64 S.Ct. 438, 88 L.Ed. 645 (1944), and again confirmed a constitutional dimension to the right of parents to direct the upbringing of their children. “It is cardinal with us that the custody, care and nurture of the child reside first in the Page 23 of 33 Motion 7 parents, whose primary function and freedom include preparation for obligations the State can neither supply nor hinder.” Id., at 166, 64 S.Ct. 438. In subsequent cases, the United States Supreme Court recognized the fundamental right of parents to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children. See, e.g., Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645, 651, 92 S.Ct. 1208, 31 L.Ed.2d 551 (1972) (“It is plain that the interest of a parent in the companionship, care, custody, and management of his or her children comes to this Court with a momentum for respect lacking when appeal is made to liberties which derive merely form shifting economic arrangements’” (citation omitted); Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 232, 92 S.Ct. 1526, 32 L.Ed.2d 15 (1972) (“The history and culture of Western civilization reflect a strong tradition of parental concern for the nurture and upbringing of their children and is now established beyond debate as an enduring American tradition”); Quilloin v. Walcott, 434 U.S. 246, 255, 98 S.Ct. 549, 54 L.Ed.2d 511 (1978) (“We have recognized on numerous occasions that the relationship between parent and child is constitutionally protected.”); Parham v. J.R., 442 U.S. 584, 602, 99 S.Ct. 2493, 61 L.Ed.2d 101 (1979) (“Our jurisprudence historically has reflected Western civilization concepts of the family as a unit with broad parental authority over minor children, our cases have consistently followed that course”); Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753, 102 S.Ct. 1388, 71 L.Ed.2d 599 (1982) (discussing the fundamental liberty interest of natural parents in the care, custody, and management of their child”); Glucksberg, supra, at 720, 117 S.Ct. 2258 (“In a long line of cases, the United States Supreme Court has held that, in addition to the specific freedoms protected by the Bill of Rights, the ‘liberty’ specially protected by the Due Process Clause includes the right… to direct the education Page 24 of 33 Motion 7 and upbringing of one’s children” (citing Meyer and Pierce). In light of this extensive precedent, the Court should apply a strict scrutiny analysis because the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment protects the fundamental right of parents to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children. The right to associate with family members was recognized by the United States Supreme Court in Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 618 (1984), as a fundamental right that triggers the strict scrutiny analysis. Family relationships, by their nature, involve deep attachments and commitments to the necessarily few other individuals with whom one shares not only a special community of thoughts, experiences, and beliefs but also distinctively personal aspects of one’s life. State v. C.M., 746 So.2d 401, 415 (Ala.Crim.App.1999). In Miller, a group of Iowa convicted sex offenders brought a class action challenging the constitutionality of Iowa’s statute that prohibited sex offenders from residing within 2000 feet of a school or childcare facility. Doe v. Miller, 405 F.3d 700 (8th Cir. 2005). The United States District Court for the Southern District of Iowa ruled in favor of the sex offenders. The State appealed. Miller at 700. The United States 8th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and remanded. Miller at 700. The Iowa statute, contrary to Alabama’s sex offender laws, did not apply retroactively to persons who established residency before July 1, 2002 or to schools or childcare facilities located after July 1, 2002. Miller at 705. Furthermore, the statute only restricted living within 2000 feet of a school or daycare. The statute did not limit who could live in the home with the convicted sex offender. Miller at 705. The Iowa statute did not prohibit sex offenders from accessing areas near schools or childcare Page 25 of 33 Motion 7 facilities for employment, it only restricted residency. Miller at 719. As cited in the Doe v. Miller case, certain intimate human relationships must be secure against undue intrusion by the State because of the roll of such relationship in safeguarding the individual freedom that is central to our constitutional scheme. Miller at 709-710. In Moore v. City of East Cleveland, 461 U.S. 494 (1977), a zoning ordinance was unconstitutional because it defined a family in such a way as to prohibit a grandmother and her 2 grandsons from living together in an area designated for single family dwellings. The United States Supreme Court held that freedom of personal choice in matters of marriage and family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Iowa statute did not restrict who may live with a sex offender in their residence. Moore at 710. The Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold and Moore recognized constitutional rights relating to personal choice in matters of marriage and family life and recognized these rights in terms of the intimate relation of husband and wife. Griswold 381 U.S. 479, 482 (1965), or intrusive regulation of family living arrangements. Moore 431 U.S. at 499 (1977). The Miller Court specifically held that because the statute did not restrict who could live in the home with the sex offender, it did not infringe upon a Constitutional Liberty Interest relating to matters of marriage and family in a way that required heightened scrutiny. Miller at 711. In C.M., a juvenile was adjudicated delinquent for sex offenses. The juvenile filed a writ of mandamus challenging the constitutionality of the Community Notification Act. State v. C.M., 746 So.2d 401 (Ala.Crim.App. 1999). The Court of Criminal Page 26 of 33 Motion 7 Appeals directed the Trial Court to rule on the constitutionality of the act. The Circuit Court ruled the act violated the Ex Post Facto Clause but did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. The State appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals held: 1. Retroactive application of the Community Notification Act provisions prohibiting juveniles from returning to their home in which another minor lived violated the juvenile’s right to Equal Protection, and violated the Ex Post Facto Clause; 2. Retroactive application of the Community Notification Act provision requiring community notification violated the Ex Post Facto Clause; but 3. Retroactive application of provisions requiring juvenile sex offenders to register with law enforcement did not violate the Ex Post Facto Clause. C.M. at 410. Several other State sex offender statutes have been found unconstitutional. These cases are recited in State v. Meyers, 923 P.2d 1024, 1037-1038 (1996). For example, the California Supreme Court found its registration statute to be a form of punishment. The California Supreme Court then found the registration requirement to be cruel and unusual punishment. In re Reed 663 P.2d 216 (1983) cited in Meyers at 1038-1039. Alaska’s sex offender laws violated the prohibition against Ex Post Facto legislation because the law included a provision providing for public dissemination of information concerning sex offenders whose convictions predated the registration act. Page 27 of 33 Motion 7 Rowe v. Burton, 884 F.Supp. 1372 (D.Alaska 1994). Rowe at 1380 cited in Meyers at 1039. The Court reasoned as follows: 1. Public dissemination provisions, which would subject the registrants to public stigma and ostracism affecting both their personal and professional lives, imposed an affirmative disability or restraint causing a punitive affect; 2. Registration was not a concept which the Court perceived to be imbued by history with a punitive connotation; 3. The act was premised on knowingly wrongful conduct of the registrant and therefore the scienter factor was present, indicating punitive effect although that factor was to be given only light weight; 4. While the registration requirement by itself may have imposed only a minimum burden, the public disclosure mechanism could have both a deterrent and retributive effect; 5. Little weight is given to the factor of whether the behavior to which the sanction applied was already a crime; and 6. The law had an alternative non-punitive purpose but the public dissemination feature of the law left open the possibility that the sanction may be excessive in relation to its legitimate non-punitive affect. Meyers at 1039; citing Rowe at 1378-1379. In Doe v. Pataki, 919 F. Supp. 691 (S.D.N.Y. 1996), the Federal District Court granted an injunction against retroactive application of the notification provisions of New Page 28 of 33 Motion 7 York’s Megan’s Law. In determining that the public notification provisions were punitive, the Court relied upon the Mendoza-Martinez factors finding that the public notification provisions: 1. Have traditionally been viewed as punitive; 2. Serve a traditional punishment goal deterrence; 3. Impose an affirmative disability or restraint; 4. Are triggered by behavior that is already a crime; and 5. Have already led to excessively harsh results. Pataki at 700-701 cited in Meyers at 1040. The Kansas registration statute addressed in Meyers did not restrict the offender’s movements within the community. The act only required registration. Meyers at 1041. The Kansas disclosure provisions, however, made more burdensome the punishment for a crime after its commission, thus the disclosure provisions violated the constitutional prohibition against Ex Post Facto laws. Meyers at 1043. The Court upheld the registration requirements but held the disclosure of the registration information violated the Ex Post Facto Clause. Meyers at 1044. Kansas v. Hendrix, 521 U.S. 346 (1997), is distinguishable because the simple fact of a conviction was not sufficient to authorize civil commitment under the Kansas law. The Kansas law permitted civil commitment of persons who had committed or had been charged with a sexually violent offense only after a hearing showing the mental abnormality or personality disorder which made the person more likely to engage in predatory acts of sexual violence. Smith v. Doe at 113 Justice Stevens dissenting. Furthermore, a conviction was not a predicate for a civil commitment. Therefore, using Page 29 of 33 Motion 7 Kansas v. Hendrix to support an argument that the Alabama statutes do not violate the Ex Post Facto law is misplaced. A sanction that: 1. Is imposed on everyone who commits a criminal offense; 2. Is not imposed on anyone else; and 3. Severely impairs a person’s liberty is punishment. Smith at 113 (Justice Stevens dissenting). Thus the Alabama Sex Offender Statutes violate Double Jeopardy and rise to the level of cruel and unusual punishment prohibited by the 5th and 8th Amendment of the United States Constitution and Alabama Constitution Article I, §9 (1901) and §15 (1901). The defendant was not required to move because he violated any residency restrictions other than living with his biological child. This is precisely the liberty interest addressed in Griswold and City of East Cleveland which found such housing restrictions to be unconstitutional. The defendant is precluded from not only living with his biological child but also from enjoying a marital relationship. His wife is denied the same Constitutional Rights. IX. Conclusion Alabama has the most restrictive, restraining, invasive sex offender residency restrictions in the United States. The Alabama Sex Offender laws as amended in 2005 go beyond civil regulation and rise to the level of punishment and liberty restraint which, when applied retroactively, violate the Ex Post Facto Clause and Due Process Clause of the United States and Alabama State Constitution. Page 30 of 33 Motion 7 Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 1520-26 et seq. violate the Due Process Clause of the 5th and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution and Alabama State Constitution Article I, §6 (1901). Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 1520-26 et seq. violate and unconstitutionally impinge upon the fundamental right and liberty of parents to live with and develop and maintain a relationship with their children. Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 1520-26 et seq. violate the Due Process Rights as guaranteed by the United States Constitution Amendments 5 and 14, Alabama State Constitution Article I, §6 (1901). Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 1520-26 et seq. are unconstitutionally vague. Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23; and 15-20-26 unconstitutionally interfere with the parent’s liberty interest in family privacy in violation of the Due Process Clause to the United States Constitution Amendments 5 and 14 and Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901) and the right to freely assemble in violation of the 1st and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution. Application of Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 15-20-26 et seq. violate the Separation of Powers Clause of the Alabama Constitution Article III, §42; Alabama Constitution Article III, §43, United States Constitution Article I, and United States Constitution Article III. Application of Alabama Code §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 15-20-26 et seq. violate the Inalienable Rights of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness in violation of Alabama Constitution Article I, §1 (1901). Page 31 of 33 Motion 7 Alabama State Statute §§15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 15-20-26 et seq. violate the Equal Protection Clause pursuant to the United States Constitution Amendment 14 and the Alabama Constitution Article I, §1 (1901) and §6 (1901); Due Process Clause pursuant to the United States Constitution Amendments 5 and 14 and Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901); the Substantive Due Process Clause, the Procedural Due Process Clause, Fundamental Liberty Interest pursuant to the United States Constitution Amendments 5 and 14 and Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901); Cruel and Unusual Punishment pursuant to the United States Constitution Amendment 8 and Alabama Constitution Article I, §15 (1901); Ex Post Facto pursuant to the United States Constitution Article I, §9(3) and §10(1) and Alabama Constitution Article I, §7 and §22 (1901), Alabama Rules of Criminal Procedure 14.4(a)(1)(i)-(viii); 14.4(2); 14.4(3); 14.4(b); 14.4(c); 14.4(d); and 14.4(e); Double Jeopardy pursuant to the United States Constitution Amendments 5 and14 and the Alabama Constitution Article I, §6 (1901); Defendant’s Right to Privacy Implicit in the Due Process Clause and other Constitutional Rights. Wherefore, the defendant moves to declare Alabama Code §§ 15-20-20.1 et seq.; 15-20-21 et seq.; 15-20-23 et seq.; and 15-20-26 et seq. unconstitutional and to dismiss all charges. The defendant requests such other further and different relief to which he may be entitled. ___________________________ Jeffrey B. Austin, Esq. (AUS 013) Attorney for the Defendant Page 32 of 33 Motion 7 MITCHELL, WINBORN, AUSTIN, & MILES 102 South Court Street, Suite 600 Florence, AL 35630 (256) 764-0582 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify on this ____ day of June 2008 I have served a copy of the foregoing upon the following by hand delivering a copy of same to the Lauderdale County Courthouse: Chris Connolly District Attorney 200 South Court Street Florence, AL 35630 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I hereby certify on this _____ day of June 2008 that I have served a copy of the foregoing upon the following via U.S. Mail, postage prepaid: Mr. Troy King Attorney General’s Office 11 South Union Street Montgomery, AL 36130 _____________________________ Jeffrey B. Austin, Esq. Page 33 of 33 Motion 7