Contrasts with Cumulative Case

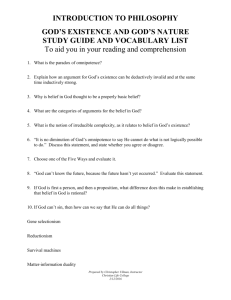

advertisement

In this section, list the principles involved with each apologetic view. Classical Cumulative Case Presuppositional Reformed Fairly eclectic in its use of various positive evidences and negative critiques, utilizing both philosophical and historical arguments, but tends to focus chiefly on the legitimacy of accumulating various historical and other inductive arguments for the truth of Christianity. The nature of the case for Christianity is not in any strict sense a formal argument like a proof or an argument from probability. It is an informal argument that pieces together several lines or types of data into a sort of hypothesis or theory that comprehensively explains that data and does so better than any alternative hypothesis. It is perfectly reasonable for a person to believe many things without evidence. Belief in God does not require the support of evidence or argument in order for it to be rational. 1 The inner witness of the Holy Spirit gives us an immediate and veridical assurance of the truth of our Christian faith Consistency: a system of belief must no lead to a contradiction. 2 Rational argument and evidence may properly confirm but not defeat that assurance. The chief interest of this method is the postulating and developing of historical evidences (one species of propositional data) for the Christian faith. Careful applications of historical principles, tempered by various sorts of critical analyses, are necessary in order to recognize and offset as much as possible the subjective element. Evidentialists engage freely in “negative” apologetics, arguing against the theses of those who would seek to defeat Christian theism. It is impossible to force anyone into the kingdom of God by our use of logic and/or evidences. There is not enough common ground between believers and unbelievers that would allow followers of the prior three methods to accomplish their goals. The apologist must simply presuppose the truth of Christianity as the proper starting point in apologetics. The Christian revelation in the Scriptures is the framework through which all experience is interpreted and all truth is known (transcendental). The goal of apologetics is to evoke or strengthen faith, not merely to bring intellectual persuasion. Correspondence: any belief must correspond with reality. Apologists, therefore, must resist temptations to contentiousness or arrogance. It seems that God has given us an awareness of Himself that is not dependant on theistic arguments. Comprehensiveness: prefer theories or systems of belief that explain more of the evidence over those that might account for less. Belief in God is more like belief in a person than belief in a scientific theory. This does not mean that there is no common ground between the believer and the unbeliever. Livability: for a belief to be true, it must be livable. Our apologetic should take special pains to present God as he really is: as the sovereign Lord of heaven and earth, who alone saves his people from their sins. As such, our argument should be transcendental. It should present the Biblical God, not merely as the conclusion to an argument, but as the one who makes the argument possible. We can reach this transcendental conclusion by many kinds of specific arguments, including many of the traditional ones. SUMMARY Evidential Begins by applying natural theology to establish theism as the correct worldview. 3 4 5 Simplicity: instructs not to multiply explanatory terms unnecessarily. (Ockham’s Razor) There are very few people who have access to or the ability to assess most theistic arguments. Classical 6 7 8 Evidential The Holy Spirit may work through the use of apologetics (just as he does through preaching or witnessing), not only bringing unbelievers to himself, but also in providing full assurance to believers (perhaps even apart from evidences (that they are the children of God. The vast majority of evidentialists are eclectic in their approach to apologetics; while they agree that their method is a viable way, it is not the only way to argue. Not only is apologetics exceptionally useful with believers; that may even be its major value. Cumulative Case Presuppositional Fruitfulness: does it produce fruitful consequences? Negatively, we should not say things to the unbeliever that tend to reinforce his pretense to autonomy or neutrality. Conservation: when an anomaly to a theory is found, first choose solutions that require the least radical revision of worldview. The actual arguments we use in an apologetic witness will vary considerably, depending on who we are talking to. It is especially useful when we can show hoe the errors of nonChristian worldviews arise, not merely from logical mistakes or factual inaccuracy, but from religious rebellion. Reformed Contrasts with Classical In this section, list the contrasts between each apologetic view. Evidential Cumulative Case Presuppositional Reformed A historical argument from miracles to God is an illegitimate move. Emphasizing the witness of the Holy Spirit is subjective. Prefers to assert the epistemic rights of the believer which does not appear to address any specific question. Too much distinction between knowing and showing. Classical argues for a two-step approach to the defense of Christianity. CC argues for a one-step method based on arguments drawn from a variety of elements that stand in need of understanding- a Christian understanding of God and reality best explain those elements. Classical places too much distinction between knowing and showing. CC stresses that basic beliefs are only prima facie justified. Classical argues that the Holy Spirit’s witness is self-authenticating. The role of the Word of God is almost entirely missing from Classical. The Holy Spirit does not tell us anything beyond what the Bible says. A third element (in addition to evidential arguments and the Spirit’s testimony) is necessary: the normative to set the rules for thinking and knowing (for a Christian that is God’s Word in Scripture). Evidence is required for all human knowledge; argument is not. Classical holds that evidence can turn against Christianity; presuppositional holds that if the evidence appears to weigh against Christianity, the evidence has been misunderstood or misinterpreted. Classical arguments for the necessity of common ground to show the truths of Christianity. Argument is not equal to evidence. Opposes the magisterial use of reason when it comes to non-believers. Fails to recognize our own human cognitive functions. Reason may be a guide to the truth, but it is not an infallible guide. Classical Contrasts with Evidential Encouraging various forms of natural theology with regard to arguments for God’s existence does not qualify as a distinct apologetic methodology or school of thought, but is merely a personally preferred style of argumentation. Resistance to a miraculous explanation of the gospel evidence arises in opposition to a miraculous explanation of the gospel evidence. Natural theologians who argue intuitively must confront in science the same obstacle as Christian evidentialists do in historynamely, methodological naturalism Cumulative Case Cumulative Case would include all the historical evidence for Christianity that Evidential offers, but would see other elements in human experience that need explanation and point to the truth of Christian theism. Presuppositional Reformed Epistemological common ground requires a more careful analysis. Alongside agreements, there is monumental bias toward disagreement. Even when an unbeliever agrees with a Christian, he does so in the interest of fighting the truth. Disagreements between believers and unbelievers indicate inconsistency in one or the other party. Does not respond to those who reject all supernatural explanations in principle. Does not respond to the argument that “extraordinary events require extraordinary amounts of evidence.” (Hume) Historical evidence alone proves little or nothing. Explanatory power is not the only factor involved in the assessment of hypotheses; hypotheses must also be judged to have some initial likelihood of being true. Contrasts with Cumulative Case Classical Claims that the witness of the Holy Spirit is identical with the cumulative case for Christianity and differentiates within it the internal or subjective witness of the Spirit and the external or objective witness of the Spirit. Affirms that while faith gives certitude that our Christian faith is true, such a subjective certitude is no indication that the tenaciously held belief is true. Never states what characteristics an argument must have to qualify as a truth. No reason is given for not regarding ontological and cosmological argument as probabilistically sound theistic proofs. Criteria are not really tests for truth per se, but rather are just criteria for determining the best explanation. Never shows how Christianity passes the tests of CC. Conservation leads to a pluralistic, relativistic conception of truth, since proponents of 2 contradictory views each applying this test determines that their view is true. Evidential Depends on Scripture in the apologetic with people who don’t allow either the trustworthiness or inspiration of the text. Presuppositional Reformed The fact that non-theists will not accept a premise in the ontological argument does not prove that they do not have an obligation to accept it. Fails to prove that the traditional theistic arguments are not demonstrably sound on his definition. Arguments. Does not solve the specific problem that non-theists fail to grant some premises of the theistic. Increases the number of arguments to which non-theists can object. Omits “Scripturality”- the most important Christian test of truth. Not presupposing the authority and consistency of Scripture, the non-Christian will find in the inadequacy of these reconciliations evidence that Scripture contradicts itself. Does not consider presuppositions. Without a clearly developed Christian epistemology, the whole cc will contain a general implausibility that cannot be remedied. Does not consider the question as to the rules of the rational game and the further question of whether these rules are religiously neutral. Disagrees that there is only one reasonable conclusion that a person can come to given the evidence. It is possible to construct a deductive argument for the existence of God with premises that non-theists are unlikely to accept. Disagrees that the failure of a compelling argument is likewise a defect in the believer’s rationality. Disagrees that the failure of a compelling argument leaves only fideism or CC as options. Disagrees that CC is the inference to the best explanation, because there are infinitely many logical explanations, so it is difficult to ensure that one has the best explanation. Reduces to inference to the best explanation that finite humans have come up with to this point. Many belief systems could pass and have passed all the tests for truth, but they can’t all be true. Evidential Cumulative Case Reformed While regularly acknowledging the importance of developing evidences of Christian theism, even within a presuppositional system, develops no historical arguments. All presuppositions are not created equal; yet assumes more truth on behalf of Christianity than is allowed for other systems. Presuppositionalism has long charged that evidential treatments subject Scripture to a more ultimate standard, but it seems clear that God not only allows but actually challenges his people to examine and witness evidential manifestations that confirm his revealed truth. Debating an issue does not demand that a position of neutrality is necessary. Christians should not be afraid of the evidence for their faith. Christians should not fear that the whole structure of reality might collapse if we don’t presuppose the faith in our arguments, or that it at least totters until the apologist for Christianity wins the debate. Theistic proofs are not the only evidence for God’s existence and the truth of Christianity. Implies that non-Christians cannot know anything. Lacking explicit knowledge of God, we cannot know things. Presuppositionalists are often long on assertions and short on argument. Not all of the “impersonal” options are the same- not all of them assume that all that ultimately exists is matter, motion, time and chance. Given that all three (religions of the book” can account for reason, it puts a heavy burden of proof on the historical evidence for the incarnation and resurrection in order to demonstrate the rational preference of Christianity over Judaism and Islam, but fails to heed its own assertions about the non-neutrality of reason and seems to suggest that the evidence is compelling to the sufficiently open-minded. Disparages “autonomous human reason,” but no philosophers have suggested that reason is the standard of truth. Contrasts with Presuppositional Classical It commits the informal fallacy of petition principii, or, begging the question, for it advocates presupposing the truth of Christian theism in order to prove Christian theism. Confuses transcendental reasoning with demonstratio quia, proof that proceeds from consequence to ground. Contrasts with Reformed Classical Evidential Cumulative Case Presuppositional The 3 reasons why we are Christians should believe that humans have a cognitive faculty that produces in us belief in God fail to show that belief in God is grounded in natural instinct or inborn awareness of the human mind rather than in the witness of the holy spirit. Externalism robs us of any assurance of knowing the truth of the Christian faith. Confuses apologetic strategy with evangelistic strategy. We must never think that because a nonbeliever remained unconvinced by our case that our apologetic has failed. Even if people tend to end up where they start, we must not forget that where they start may well be partially the result of argument and evidence. Overlooks the leavening apologetics has on culture. If out of deference to the “postmodern mentality” we abandon natural theology and Christian evidences and tell people to attend to the inner divine sense, we may reap in the next generation a whirlwind of religious relativism and pluralism. After exaggerating the definition of epistemic evidentialism and its relation to classic foundationalism, Reformed epistemologists frequently denounce both; but by the very way they argue, the support the notion that faith needs an adequate basis. Belief in God as properly basic opens Reformed epistemology to an array of criticisms. The absence of detailed positive (especially historical) evidences for Christian theism creates a question how we can know that Christian theism is actually true. Various counseling strategies should be employed when ministering to those who suffer emotional quandaries regarding their faith. Needs a detailed investigation of the role of the Holy Spirit’s testimony. Rational believability is about the weakest claim that can be made for Christian theism. The Christian theistic revelation is the very criterion of truth, the most certain thing we know. We are not merely permitted to believe in God until we are persuaded otherwise; father, we are obligated to believe in Him. Scripture implies that our faith governs our reason. Christian faith must be something more than a belief we are rational in holding. Weak treatment of the role of the Bible and Holy Spirit. The starting point for our beliefs is not only our socio-cultural upbringing, but also from belief or unbelief in the true God. As Christians, our socio-cultural background is far less important in gove3rning our lives than our covenant with the almighty God who tells us to do all things to His glory. In this section, list the similarities between each apologetic view. Classical Similarities with Classical Classical Similarities with Evidential Evidential Epistemologically, we need a starting point for religious knowledge. Evidence is secondary to truth. Apologetics does not exist in a vacuum. Bridges must be built between theory and practice. Arguments from miracles can be part of a cumulative case for theism. Evidential Cumulative Case There is a significant difference between the epistemic structures of believers and unbelievers. The role of the Holy Spirit explains the tenacity of a Christian’s belief. Presuppositional Reformed The testimony of the Spirit is a self-authenticating, immediate apprehension of the truth of the gospel, that it is not dependent on arguments, and that it “overwhelms” contrary arguments. For those who know Christ through the Spirit’s witness, arguments are subsidiary. The spirit’s witness is infallible, our arguments fallible. Hyper-classical apologetics assumes the magisterial use of reason- it stands over and above the gospel like a magistrate and judges its truth or falsity. The distinction between knowing and showing seems both to fit human experience and to offer a genuine insight into human cognition. There is no simple or unidirectional logic of believing. Cumulative Case Presuppositional Reformed Correct in claiming that a onestep approach to apologetics is possible. Commitment to evidentialist apologetic approach does not predetermine one’s epistemological stance. Realizes that there are no brute facts; facts come to us through theories about the world. There is common ground between believers and unbelievers. There are a variety of ways to defend God’s existence and the Christian faith. Right in cautioning the apologist on the use of scriptural evidence. Apologetics may be done in one step because every fact of creation reveals God. Therefore the apologist can begin anywhere. Historical evidences won’t work except in the context of a theistic worldview. Historical occurrences are not brute facts that interpret themselves. Scripture has important things to say about the way we study history- some biases are good. There is ontological common ground between the believer and unbeliever and these can be apologetically useful. Agrees that more often than not we have come to a considered judgment about some issue with less than adequate or compelling evidence. Similarities with Cumulative Case Classical A successful apologetic for the Christian faith should be in an appropriate sense a cumulative case and is best undertaken by a community of scholars. Evidential Embraces an eclectic approach to apologetics. Seven tests for truth is helpful, if standard, to those developing a methodology. Takes seriously the work of the Holy Spirit. Speaks highly of several arguments for God’s existence. Claims that religious experience is superior to the non-religious response. Includes morality, human nature, special revelation and fulfilled prophecy. Provides Jesus’ testimony as the primary reason to believe God has spoken to us. Argues that postmodernists’ actions deny their own teachings. Emphasizes constructing an entire case rather than stand-alone arguments. Cumulative Case Presuppositional Reformed Agrees with definition of demonstrative soundness. Agrees that other theistic religions and atheism are systems of unbelief. Recognizes the problem of epistemic normativity. Agrees with other tests of truth. Agrees that an argument for God’s actual existence can remedy some of the implausibilities of a report of religious experience. More often than not we have come to a considered judgment about some issue with less than adequate or compelling evidence. Similarities with Presuppositional Classical Evidential Theological rationalism is a false doctrine. The Spirit creates faith in the heart… and that faith may or may not arise through an argumentative process. It is an epistemological transcendental argument: an argument for a reality based on that reality’s being the very conditions even of the denial of that reality. Glorify God in all our apologetics. Apologetic task is to be carried out without pride. Our personal systems are not as important as honoring God and serving others. Our approaches are person relative and individual responses are necessary. Both Christian and non-Christian should view their worldviews against the other paradigms, giving each an equal hearing. Accepts data where it is found. Rightly attacks the notion of neutrality. Truth serves as our point of contact, and the evaluation of worldviews may come on several fronts, such as cause, purpose, and history. Supports the notion of probability, that many of our arguments are only probable. Cumulative Case Reminds us that all arguments have presuppositions. It demonstrates that direct “proofs” are not the only proofs. Presuppositional Reformed Argument can play a positive role in coming to faith. Keenly aware of the limits of arguments and the influence of our presuppositions on our believing. Roots epistemological commitments in Scripture and finds their support for the view that we can offer proof for our beliefs. Cognitive facilities are designed by God. Noetic effects of sin- our cognitive faculties are distorted primarily toward ends that enhance a person’s self-interest. Similarities with Reformed Classical Belief in God does not require the support of evidence or argument in order for it to be rational. The theistic arguments do provide some non-coercive evidence of God’s existence. Few people are directly converted through the presentation of apologetic arguments. Evidential Cumulative Case Presuppositional Combines foundationalism with elements of existentialism. Epistemic evidentialism needs to be abandoned in favor of a less restricted, more defensible system of acquiring knowledge. Espouses the use of evidences regarding God’s existence- noncoercive, person-relative arguments that are helpful for some, though not all. Encourages the use of negative apologetics; i.e., critiques of skepticism, relativism, and pluralism. Strategy of exposing unbelievers to “situations where people are typically taken with belief in God.” Models epistemic and methodological humility. Encourages apologetic variety in both systems and arguments. Does not require evidence to support all beliefs everywhere. Most people do not have access to, or the intellectual ability to evaluate, the theistic proofs. God has given us some immediate, direct awareness of Himself. Personal relations require trust, commitment, and faith. We ought to pay greater attention to how real people actually acquire belief in God. The Bible’s data on apologetic methodology is compatible with a vari8ety of approaches. Arguments alone, no matter how well constructed and defended, will not produce faith. It can be rational to believe in God (and in other things) without argument. Warranted belief does not need to be based on argument, but it does need to be based on fact, on reality. We can start with a belief in God as a truth that we can just accept and reason from. Belief in God, like belief in other persons, demands “trust, commitment and faith.” Multitudes of situations can evoke belief in God, with or without argument. Theistic arguments aren’t of such power and illumination that they should be expected to persuade all rational creatures. Reformed