Kerry Ryden, 2007F

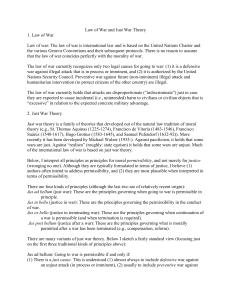

advertisement