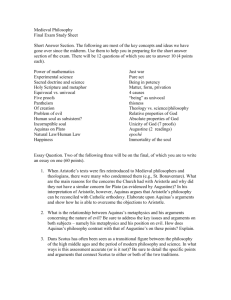

history of western philosophy_unit2_2012_draft2

advertisement