12-12-11 Notes Approach With Caution bijeenkomst_draft final

advertisement

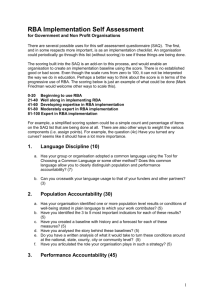

Draft report “Approach with Caution”: Sharing event on approaches to sustainable development 11 December 2012, at IUCN office Present: IUCN.NL: Heleen van de Hombergh, Cas Besselink, Jan Kamstra, Liliana Jauregui, Rob Glastra, Mark van de Wal, Joost van Montfoort, Sarah Doornbos, Jan Willem den Besten, Caspar Verwer; Wetlands International: Maria Stolk; Both ENDS: Christa Nooy, Tobias Schmitz, Huub Kistermann., Annelieke Douma, Leonie Weezendonk, Martien Hoogland, David Aparici Aim of this meeting is to share Both ENDS knowledge, experiences, but above all to address remaining challenges together within the Ecosystems Alliance. 1) Background Working Paper “Approach With Caution” – presentation by Christa PSO provided Both ENDS the opportunity for a learning process with partners on approaches to address environmental and social inequity challenges. Key challenges are: access rights to natural resources; improved resource management skills; ability to enter markets; developing and negotiating alternative resource management and development options. Both ENDS identified three approaches it applies with partners in their joint work: PLUP (Participatory Land Use Planning) NA (Negotiate Approach) RBA (Rights Based Approach) These three approaches are either mainstream practice or evolving work in progress with partners, and had key questions that needed to be answered to direct the evolution and enhance effectiveness. A reflection took a place with ten partners on experiences of the last ten years and to look ahead. These include the EA partners: CPA (Philippines; FARN (Argentina); ICV (Brasil); M’bigua (Brasil); Nape (Uganda)l Telapak (Indonesia). The results were documented in the Working Paper Approach with Caution, which is available at http://www.bothends.nl/en/Publications/ 2) Working Paper “Approach With Caution” – presentation by Tobias Both ENDS sat down with partners to clarify on approaches, and identify the challenges and solutions per approach on three levels: concepts/ideas; instruments and implementation. NA Concept/Ideas (Challenge/solution) Instruments (Challenge/solution) Experience with implement (Challenge/solution) PLUP RBA This resulted in an Agenda for the Future, in which the main actions are identified per approach: Negotiated Approach (NA): Create a clear / unambiguous message by: Sticking to one set of concepts; Develop tools but leave them as flexible options Clarify the role of local institutions like Water User Associations Be precise about how the NA deals with power imbalances Clarify how environmental protection is incorporated within the NA Participatory Land Use Planning (PLUP) Clarify how PLUP deals with power imbalances; Clarify relationship PLUP / land reform; Clarify how PLUP varies with different kinds of land rights; Develop means to upscale: how is policy influenced to adopt local planning ideas? Rights based Approach (RBA) Clarify how the RBA deals with legal pluralism (whose law is being applied?) Challenge: legal development and governance frameworks are often different worlds. How to bring these closer together? Develop clear set of practical tools (like amicus curiae) Questions and Remarks: R: (Rob Glastra) the Agenda for the future is most interesting to take further within the EA. Q: (Jan Kamstra) When to use which approach, they overlap in practice, and what is the point of continued discussion and learning on them. A: Approaches are way to put activities of several organizations into one common framework, which makes it easier to find commonalities in visions and activities and to have a structured discussion with partners. This helps to identify common challenges and opportunities for cooperation. Q: Mark van de Wal refers to massive large-scale mining activities Africa. What approach to apply here, the RBA? A: Tobias: in such case RBA alone is not enough; this also requires a more holistic approach that for example includes principles and tools for negotiations with governments; facilitation of bottom up, multi stakeholder processes aimed at inclusive natural resource management, and the design of alternative scenarios for NRM. R: (Jan Willem): the starting point can be different then local communities; you can also have an economic approach. What follows is a discussion on approaches and their shortcomings. The HCVA tool is mentioned as useful in PLUP and the landscape approach, although it lacks a well developed methodology for incorporating social and cultural values; Tobias knows of a nice tool (Eco mapping) for exactly this purpose that has been used in Benin. 3) CASE: Participatory Land Use Planning in Kalimantan (ICRAF)– presentation by Leonie Both ENDS and ICRAF worked with local NGOs to have existing community maps legalized by the district government in Sanggau, West-Kalimantan. The “Strategic Rural Area” (a new classification in the spatial planning law) was brought forward to the local district government by the local NGOs. This was done by multi-stakeholder meetings and policy memo’s, as a cooperative way to make land-use planning in Sanggau more inclusive of rural communities. Input was also given in the revision of the spatial plan. This resulted in “Simulation of One map”, in which all district government offices provides spatial data of the mining, forestry and palm oil concessions. This map was overlaid with community maps, so it now shows the overlaps of community areas and concession areas. The district government does not want to publish the map, and the Strategic Rural Area has not been included in the spatial plan yet, so the process is still on going. For the presentation, see: http://prezi.com/iqwtyas9kyj7/present/?follow=qv1yliqcwvz7&auth_key=uenk 57v#3_4253050 Questions and remarks: Q: What is the status of the community maps? Their legality very much depends on who is making them; they can create a lot of conflict, not just towards governments or other stakeholders, also among community members. A: The project makes use of already existing maps, made by local NGOs and communities. These groups in Kalimantan have years of experience in community mapping. The status and getting recognition from all stakeholders and especially from government is one of the main challenges in PLUP and of this project. Q: Why was the district government not requested at the start of the project to allow for publication of the One Map? A: Over asking local government at the beginning of a negotiation process may obstruct its participation. The local NGOs went through a joint planning process with government; with the One Map as a result. This is in itself a success. It is taking small steps at the time. Q: To which approach does the case link, to PLUP, NA, RBA? It’s difficult to see. A: This case strongly relates to PLUP because of focus on spatial planning and the use of community maps. Q: What’s the starting point? Local community interest? Plantation, mining plans? A: ‘Burning issues’ at several levels evoked action here, such as conflicts between plantations, government, communities which triggered conflict resolution by local NGOs. The ambition by the West- Kalimantan province to exploit more palm oil plantations amongst others in response to the European Renewable Energy Directive on biofuels is an additonal driving force for local communities and NGO’s to continue. 4) Case: Negotiated Approach in Uganda (NAPE) – presentation by Tobias There is an urgent need to empower local actors along Lake Albert to claim their rights to water, land and natural resources within a framework of mediation and dispute resolution. Over the last two decades, the Albertine region has been subject to a range of forces that have resulted in a rapid transformation of its economy and its ecology. Community livelihoods on the shores of Lake Albert are being threatened by rapid population growth, the degradation of environmental resources and most recently by activities linked to oil exploration and extraction. The discovery of oil has generated a paradox in Uganda. On the one hand the Albertine region area has been catapulted from the margins of economic and political priorities to absolute top priority in the country’s National Development Plan. On the other hand, these developments are being superimposed on an area which has both a complex history of land use and is a site of immense biological diversity and natural beauty, featuring seven of Uganda’s ten national parks. This generates two fundamental contradictions: one between the universal need for secure land titles for economic advancement and the powder keg of contradictory and conflicting land claims in the area, and another between an economic scenario based on fossil fuel extraction and an economic scenario based on the conservation of the natural heritage and tourism. Bold steps are needed to create clear mechanisms for conflict resolution and coherent, inclusive plans for natural resources governance spanning water resources management, the protection of biodiversity and land use planning. Without this, local communities, traditional authorities, refugees, oil companies, central government institutions and institutions committed to the conservation of nature will increasingly face each other in a stand-off with high economic and environmental stakes on all sides. The need for participatory governance There is an urgent need for a publicly endorsed and detailed vision for the future of the Albertine region, as well as for a robust system to oversee the implementation of such a framework. The enormous natural wealth of the Albertine region holds the potential for the prolonged improvement of local livelihoods, the protection of the rich natural heritage of the country and balanced economic development. Sustained economic growth and effective conservation of natural resources both require effective channeling of the needs and concerns of the citizenry into a governance framework that responds to their ambitions and facilitates sometimes tough decision making on alternative scenarios for change. Government and traditional authorities may claim to act in the public interest but cannot prove that this is the case unless the contents of proposals emanate from local needs and are negotiated through by the various stakeholder groups which have an interest in the area. While the oil sector will strongly affect the western region of the country, the establishment of strong national and regional institutions for oil governance has not progressed and there is growing conflict around issues of access to land and other resources on the shores of the lake. In response to the first confirmed discoveries of oil in 2006,an Oil and Gas Policy was developed in 2007 and published in 2008, 3 oil bills were developed in 2012 . Unfortunately these policies and laws provide little security for local communities, and contain confidentiality clauses that may be used to limit the flow of information. By contrast, the Ugandan constitution guarantees public participation in development planning and the Environment Act affirms the right of communities to participate in environmental planning and environmental impact assessment. In the wake of oil exploration and extraction, local communities have been displaced in some areas for the construction of oil related infrastructure. Soldiers have moved in to ‘protect’ oil rich areas and NGO’s have been prevented from communicating with communities in the area, despite the existence of basic civil liberties that protect the free movement of people in Uganda and the freedom of assembly. All these factors serve to limit the capacity of local institutions to face up to latent and manifest conflicts and plan the way forward in an inclusive and reconciliatory manner. Community livelihoods and NGO responses The livelihoods of local communities along Lake Albert are historically based on fishing, cattle breeding and, where land is fertile enough, agriculture. However, fish stocks in Lake Albert have dropped, grazing land is becoming degraded, population pressure on the land is increasing and land care programs are required to maintain the limited fertility of the thin tropical soils. The influx of Congolese migrants as well as entrepreneurs from other parts of Uganda has increased the pressure on local resources even further, leading to tensions over access to land with local communities. Questions and Remarks: The case provoked several questions and comments, amongst others regarding the Democratic Governance Facilitity. Tobias is quite positive about the proposal submitted to the DGF about which we will hear more in January. There are also possibilities for exchange among EA partners about each others’ work: until now the partners have been focusing on their own work and have not had much time to visit each others’ project sites. Furthermore there is quite a lot of added value to be had in holding a two country workshop to bring together actors on both sides of lake Albert to discuss common concerns. 4) Case presentation RBA in Argentina (FARN) – presentation by Tobias Protecting the Matanza-Riachuelo Basin in Argentina In Argentina, five organisations in civil society worked together to protect the most polluted river basin in the country, i.e. the Matanza-Riachuelo basin. In 2002, residents of La Boca neighbourhood in Buenos Aires City approached the Ombudsman to request its intervention in the pollution of the basin, which led to studies into the precise nature of the problem. The information contained in these studies was incorporated into a lawsuit against the National Government, the Province of Buenos Aires, the Municipal Government of Buenos Aires and 44 private enterprises for damages suffered as a result of the pollution of the river. The case came before the National Supreme Court in 2004, leading to a judgement in 2006 that ordered the defendants to submit a clean up plan for the basin as well as requesting reports from the private enterprises detailing the measures they would take in order to halt and reverse the pollution of the area. The response of the authorities was to be presented before public hearings, of which the first was held in September 2006. During this hearing, the Riachelo Basin CleanUp Plan was presented, and an inter-jurisdictional Committee on the Basin was created to enable integrated planning of the management of the river. In 2008 this was followed by a Supreme Court ruling that determined the liability of the various authorities and indicated the obligations of the various government bodies in cleaning up the river. Moreover the court ruled that the National Ombudsman and the NGOs participating in the case could establish a Chartered Body which exercises control over the clean up plan. Because the National Government has been slow to provide access to information, the NGO FARN established an online monitoring platform providing citizens with information on the state of the river. (see also the working paper: Box 4.4) Questions and Remarks: R: (Maria): In the EA country programme, WI is active in the lower part of the river basin. We actually need more of a common insight in what is being done in the country programmes and the International Component Q: (Maria): How can we use the expertise of FARN as a tool on integrated land use planning. R: (Heleen): This case is also interesting from an international perspective. 5) What next? Challenge is to address environmental and social equity challenges together, to facilitate exchange and to enhance the effectiveness of isolated initiatives. Key challenges to address are access rights to natural resources; improved resource management skills; ability to enter markets; developing and negotiating alternative resource management and development options. Possible steps: - Create a common insight in what is being done in the country programmes and the International Component - Identify what is being done in the country programs in relation to approaches to sustainable development, and what common challenges/ questions are. The country workshops are important moments for exchange in the context of linking and learning between NGO’s locally and internationally and we need to reserve time and funds to make this possible. - The last slides of the presentation with challenges per approach are a good starting point for creating common ground for joint action. IUCN and WI can add their challenges/questions to this list. This can then be addressed in the Learning Agenda. - Share the 2013 plan on action on the Learning Agenda and provide inputs just as we have done on the IC Theme 1