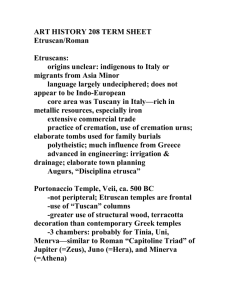

Etruscan Art core slide list

advertisement

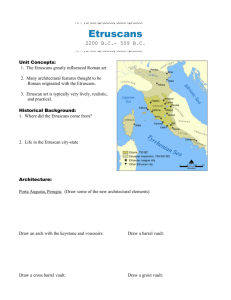

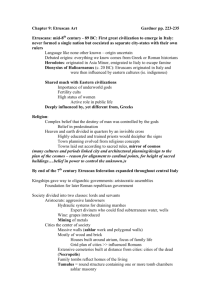

Etruscan Art Ancient History of the Italian Peninsula The archaeological record indicates direct contact between the northern and southern parts of the Italian peninsula, Sicily, and the Lipari Islands. The Villanovans flourish in the northern and western parts of the peninsula, the Etruscans prosper along the coast just north of Rome, and the Greeks begin to colonize the southern half of the peninsula and Sicily. The Roman Republic is established in 509 B.C. and, through conquest and diplomacy, acquires vast territories as subject provinces. Political rivalries in the first century B.C., however, lead to civil wars and the eventual collapse of the Republic. The principate of Augustus is established in 27 B.C. and, thus, begins the Principate or Roman imperial period. Before the days of ancient Rome's greatness, Italy was the home of a nation called Etruria, whose people we call the Etruscans. Its civilization prospered between 950 and 300 BCE. in northwestern Italy — in a region between the Arno River (which runs through Pisa and Florence) and the Tiber (which runs through Rome). These people rose to prosperity and power, then disappeared, leaving behind many unanswered questions concerning their origin and their culture. Because little Etruscan literature remains and the language of inscriptions on their monuments has been only partially deciphered, scholars have gained most of their knowledge of the Etruscans from studying the remains of their buildings, monuments, vast tombs, and the objects they left behind, notably bronze and terra cotta sculptures and polychrome ceramics. Among theories about the Etruscans' origins are the possibilities that they migrated from Greece, or from somewhere beyond Greece. Perhaps they traveled down from the Alps. Or, as their pre-Indo-European language might suggest, they may have been a people indigenous to today's Tuscany who suddenly acquired the tools for rapid development. The uncertainty is held unresolved. Theirs was not, however, a centralized society dominated by a single leader or a single imperial city. Rather, towns and hill-top villages (many of which survive to this day, albeit with few traces of their Etruscan origins) appear to have enjoyed considerable autonomy. But they spoke the same language, which also existed in a written form. Further, their religious rituals, military practices and social customs were largely similar. For their Greek contemporaries and Roman successors, the Etruscans were clearly a different ethnic group. Double Flute Player from the Tomb of the Leopards, Tarquinia Fishing Scene, Tomb of Hunting & Fishing,Tarquinia The Capitoline Lupa 6th Cent BCE She-wolf also known as the Capitoline Wolf bronze ca. 500 B.C.E. (with Renaissance additions—the twins Romulus and Remus) Chimera of Arezzo, 4th B.C. Canopic Urn, Terracotta Ossuary, 7th B.C. Etruscan Perfume Bottles in Animal Shapes Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from The Bandataccia Necropolis, Cerveteri, 6th B.C. Sarcophagus of the Married Couple from The Bandataccia Necropolis, Cerveteri, 6th B.C. (Detail) Canopic Urns, Impasto, 7th B.C Side view Statuette of a Woman, 2nd B.C. Standing Woman Reminiscent Images in Modern Art Alberto Giacometti was born into a Swiss family of artists. His early work was informed by Surrealism and Cubism, but in 1947 he settled into producing the kind of expressionist sculpture for which he is best known. His characteristic figures are extremely thin and attenuated, stretched vertically until they are mere wisps of the human form. Almost without volume or mass (although anchored with swollen, oversize feet), these skeletal forms appear weightless and remote. Their eerie otherworldliness is accentuated by the matte shades of gray and beige paint, sometimes accented with touches of pink or blue, that the artist applied over the brown patina of the metal. The rough, eroded, heavily worked surfaces of "Three Men Walking (II)“ (at left) typify his technique. Reduced, as they are, to their very core, these figures evoke lone trees in winter that have lost their foliage. Within this style, Giacometti would rarely deviate from the three themes that preoccupied him—the walking man; the standing, nude woman; and the bust—or all three, combined in various groupings. Menead Antefix, 6th B.C. Gorgon Antefix, 6th B.C. Barrel oinochoe, 8th–early 7th century b.c.; ItaloGeometric Italian peninsula, possibly Campania or Etruria Terracotta H. 13 1/4 in. (33.5 cm) Calyx-krater with theatrical scene, ca. 400–390 b.c.; Red-figure. Attributed to the Tarporley Painter Greek, South Italian, Apulian. Terracotta The actor in the center is standing on his toes with his hands raised as if he were suspended from a post; out of his mouth come the words, "he has bound my hands above." Evidently he is being punished for a theft. The stolen goods—a dead goose and a basket—lie on a platform to the right. Also on the platform is an old man or woman, who gestures as if in remonstrance, uttering the words "I shall furnish [testimony]." To the left is the guardian of the prisoner; he holds a stick as if ready to beat the thief. Source: Attributed to the Tarporley Painter: Calyx-krater with theatrical scene (24.97.104) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art Chariot, late 6th century b.c. Etruscan; From Monteleone, Italy Bronze H. 51 1/2 in Source: Chariot [Etruscan; From Monteleone, Italy] (03.23.1) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art Vocabulary • • • • • • • • Archaic Smile Antefix Terracotta Etruscan Red Figure Canopic Jar Tomb paintings Funerary Art