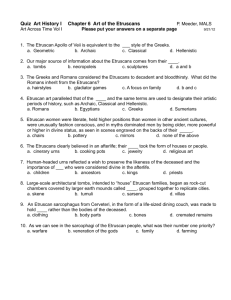

Etruscan Women - People Server at UNCW

advertisement

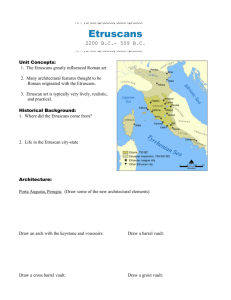

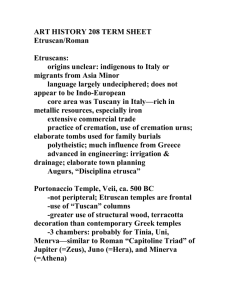

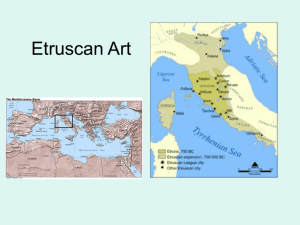

Etruscan Women Images of an Egalitarian Society Although we have many inscriptions in the Etruscan Language, we cannot read it. Consequently most of our information about the Etruscans comes from •Their art •Prejudiced accounts by Romans, for whom they were the “bad guys” of history; and •Prejudiced accounts by the Greeks, who were scandalized by the freedoms of the women Small Etruscan bust of Juno, 300-100 BCE The Etruscans shared in the culture of the 6th century BCE and later Mediterranean. Their art was influenced by Greeks; they made statues in Terracotta very similar in style to what the Greeks made in marble. They imported a lot of Greek pottery, and as with other Italian cultures, some of their own wares resembled Greek work. This map shows the extent of the Etruscan area of political influence in the 6-5 cent. BCE. There were other Etruscan holdings to the south as well. Women’s Standing Mirrors like this one, incised with mythological themes, are a popular Etruscan item. Many of the mirrors have inscriptions identifying the mythological characters. This shows that women were expected to easily combine their interest in beauty with literacy. Women’s tombs are as rich and as common as men’s, and women’s artifacts are prevalent. Women were apparently equal sharers in the society’s resources. Women’s names and images show up frequently in inscriptions as well, showing their claim to public honor. This ivory pyxis (makeup box) was very valuable; the materials were imported from Egypt and the decorations beautifully carved. The animal motifs are a common Etruscan theme. Notice the Mistress of Animals figure on the bottom row. This scene from a tomb painting shows women and men both sharing in a banquet. A nude slave boy serves them. This was scandalous to the Greeks who visited Etruria, since they were unaccustomed to men and women sharing such celebrations. Theopompus (4th c. BCE) was appalled! Most of the Etruscan art that survives is funerary art, simply because the tombs, buried for 2000 years, remained intact. Funerary art may show a different realm of experience from other forms of art. One consistent theme throughout Etruscan art seems to be the shared affection of husband and wife. Sarcophagi such as this one show them in a fond embrace, the husband’s arm protectively around the wife, as they recline on a banquet couch. The same togetherness found in the banquet continues into the afterlife. Some Etruscan sarcophagi show couples nude or lightly covered, indication that in iconography at least, female nudity was similar in meaning to male nudity and implied, probably, pleasure and fertility. Theopompus says that the Etruscans practice wife sharing (not strictly for procreation either), and that the women exercise, take care of their bodies, and expose them casually. Theopompus also comments that the Etruscans raise all the children who are born, not knowing whose they are. Did women have the legal right to decide this issue? On this sarcophagus, the couple is shown embracing in bed. Married sexuality and friendship extends into death. Apparently assertions of pleasure (dancing, sex, banquets) were important elements of the Etruscan response to the finality of death – as well as of their lifestyle (if you believe Theopompus . . .) OK, not all Etruscans are young and beautiful, even on their sarcophagi . . . Like the Greeks and Romans, Etruscans had athletic events and public entertainments. In contrast to Greek practice (but aligned with Roman custom) Etruscan women attended athletic events and games; their art sometimes shows them in the audience. Music and Dancing Both men and women are shown dancing; sometimes female professional dancers seem to be portrayed. What is the status of these entertainers? Is it comparable to that of Greek dancer/musicians? This lampstand portrays a female dancer playing cymbals, a custom the Greeks and Romans associated with the East. Linguistically and in some elements of material culture, the Etruscans may be related to the peoples of Asia Minor. This Etruscan tomb painting shows a very expressive dance. Is it in a funerary context? Does it represent social or ritual dancing? Is the performer professional or an individual associated with the deceased on whose tomb the painting was found? Why is dance so commonly portrayed in tombs? In another tomb painting, men and women dance together in this expressive mode. Here a line dance of young women is shown. Such dances were common throughout the Mediterranean and Europe (and in many other societies as well). The Greeks (cf. Alkman’s Parthenaia) celebrated their maidens’ dances; the Romans were not very focused on this sort of entertainment. Tomb of Hunting and Fishing This tomb painting shows an explicit sexual scene. Note also the lower border design which has a distinctly erotic flavor. Another tomb painting shows a scene of two men, one penetrating and one receiving oral sex from a woman, both whipping her – scholars think this might portray a Dionysian rite – or are we back in the erotic world of the Greek hetaira? Other tombs show other erotic scenes, including male homoeroticism. Etruscan Religion Etruscan religion included a system of learning the will of the gods, haruspicy, which meant reading omens from many different sources, among them the entrails of sacrificial animals. The Etruscans (under Greek influence?) also personified their gods, though like the Romans, the equivalence wasn’t too good. In the center of each Etruscan center was a temple dedicated to the Triad of Tinia (Juppiter), Uni (Juno) and Minerva. This mirror shows Chalchas (from Greek mythology) reading omens in the Etruscan fashion Etruscan iconography of their gods could be very different from the Greek. Here the sun god Usil (not looking too much like Apollo) runs across the waves in winged shoes. In this mirror, Minerva assists Hercules. Some Etruscan sanctuaries show many kourotrophos figurines, with votive figurines of men, women, children and animals, highlighting the Etruscan focus on family affection. This woman holds a pomegranate in her hand, a symbol often associated with Kore/ Persephone, who was widely worshipped among South Italian Greeks. Perhaps the Etruscans also favored this goddess with votive images. This ivory figurine of a nude woman is a theme not commonly seen in Greek or Roman art, but apparently fairly common for the Etruscans. It uses some of the conventions for portraying nude men – again indicating that female nudity had a different meaning for the Etruscans than for the Greeks & Romans. She holds a breast with one hand, and a fruit (pomegranate? Apple?) with her other – both fertility indicators. The figurine may represent the Etruscan Venus (Aphrodite); Aphrodite was shown nude in Greek and Roman art, though in more directly sensual contexts. Juno Etruscans and Romans In contrast to Roman naming practices, Etruscans gave their children a wide variety of names (more like Greek practice) Apparently (from inscriptional evidence) women’s names were also important in describing family genealogy. Women apparently passed their social rank to their children (in contrast to Rome where the father’s family officially mattered). The Etruscans had an alliance of cities, which were ruled by kings, and early in Rome’s history, Rome was subject to Etruscan rule. Roman history abounds with stories of Etruscan oppression and tyranny, along with dislike of kings as opposed to the Romans’ Republican mode of government. Women are often the key symbolic figures in such stories. Roman women such as Lucretia and Cloelia exhibit Roman virtues and inspire Roman political acts. Etruscan women, such as Tanaquil, symbolized to the Romans the proud dominance of the enemy. Tanaquil read the omen that made her husband, Lucius Tarquinius, the king of Rome. Her ability in reading omens may signify a difference in Etruscan and Roman views of women’s sacred abilities. In both societies, reading omens was important for many public events; the microcosm and macrocosm reflected the ordinary cosmos. But in Rome, men were the augurs; women may have shared that ability in Etruria. The End of Etruscan Dominance Etruscan military expansion occurred at a time when most of the other peoples of Italy were less wealthy and less technically advanced. It was led by individual kings or leaders, rather than the focus of the entire people. After a defeat by Greeks in Syracuse, Etruscan power waned. By c. 350 BCE, Romans had asserted their dominance in Italy. Although Etruscan langauge persisted into the second century BCE, their culture waned and was incorporated into the Roman world. Etruscan temple at Orvieto finis