“Its” CP - Open Evidence Project

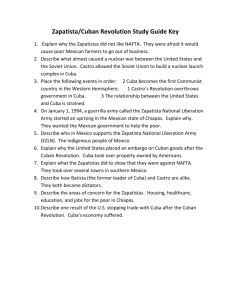

advertisement