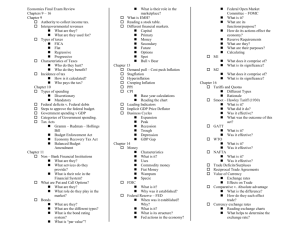

Keynesian Economics Good Bad

advertisement