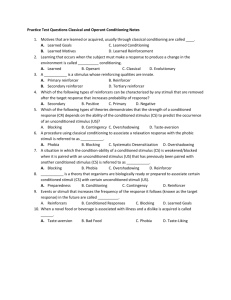

Chapter 2 Early Behaviorism The Beginnings of Scientific

advertisement

Chapter 2 Early Behaviorism The Beginnings of Scientific Psychology The Structuralism movement was in full swing in Europe (Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener) The onset of Functionalism began in the United States (William James) Introspection was the primary research methodology; however, a more scientific method, psychophysics, was emerging Wilhelm Wundt (1832 – 1920) Born in Mannheim, Germany Upbringing was extremely strict Early school career was difficult and very unsuccessful Fascinated by anatomy and the mysteries of the brain while in college Obtained a doctorate by age 24 Founded the psychological lab at the University of Leipzig Wrote more than 500 books and articles Early Psychophysics Early psychologists were seeking through psychophysical measurements the least amount of stimulation required for sensation (i.e., absolute threshold). Determining a generalized absolute threshold is not possible as some people are more sensitive than others. For each individual there is a lower limit below which a stimulus will never be detected and an upper limit above which it will always be detected. Between the two, there is a point at which it will be detected 50% of the time. This point is called the absolute threshold, although it is more approximate than absolute. Psychophysicists tried to measure not only absolute thresholds but also what they called the differential threshold often referred to as the just noticeable difference (JND). JND = the least amount of change in stimulation that would be noticeable Max Weber concluded that JNDs are a constant proportion of a stimulus (i.e., Weber’s Law). Weber’s Law A graphic portrayal of Weber’s law. As intensity of stimulation increases, proportionally greater increases in stimulation are required if they are to be noticeable Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849 – 1936) Set out to become a priest like his father Performed poorly in elementary school While in seminary, he became fascinated with Russian translations of Western scientific writings with Darwinian overtones Left the seminary to pursue studies at the University of St. Petersburg in animal physiology and in medicine Began his famous classical conditioning experiments at age 50 While visiting the United States at age 74, he was mugged in Grand Central Station Insisted he was a physiologist not a psychologist, and fined any laboratory assistant who used psychological rather than physiological terms Classical Conditioning Pavlov’s most famous experiments resulted from almost accidental observations. While studying digestive juices, Pavlov noted that some dogs created saliva prior to feeding. In seeking a scientific explanation for the dogs’ early salivation, he created the now-famous experiments. Pavlov demonstrated that not only could the sight of food eventually bring about salivation in his dogs, but almost any other distinctive stimulus could have the same effect if paired with food often enough. What Pavlov first noticed was that the sight of the handler alone was enough to cause many of his experimental dogs to salivate. Through further experiments, he studied the learning processes involved. In these experiments the stimulus food or other stimuli such as a buzzer that is paired with the food, which are controlled by experimenter, are independent variables. The dogs response (salivation, in this case) is a dependent variable. In his demonstration, Pavlov refers to the food as an unconditioned stimulus (US). The salivation in response to the food is called an unconditioned response (UR). An unconditioned response is a response that occurs without any learning. What Pavlov showed repeatedly is that if a US (food, for example) is paired with another stimulus often enough, this other stimulus will eventually lead to the response originally associated only with the US (in this case, salivation). If a buzzer is sounded every time food is presented to the dog, eventually the buzzer—called a conditioned stimulus (CS)—will elicit the response of salivation—now a conditioned response (CR). In his experiments, Pavlov often placed his dogs in a harness like this one. Food powder (an independent variable controlled by the experimenter) can be placed either in the dog’s mouth or in the dish. A tube is surgically inserted into the duct of the parotid gland so that the amount of saliva produced (a dependent variable) can be measured as it drops down the tube, causing movement in a balancing mechanism at the other end of the tube. This movement is in turn recorded on a revolving drum. In the experiment illustrated here, the US (food) is paired with a CS (light shining in the window). Classical conditioning. Food (US) elicits salivation in a dog, but a buzzer (NS) does not. After successive pairing of food and buzzer, the buzzer (CS; an independent variable) begins to elicit salivation (CR; a dependent variable). Learning through stimulus substitution Signal learning Learning always begins with an unlearned response (UR) that can reliably be elicited by a specific stimulus (the US). This unlearned stimulus-response unit is called a reflex. Reflexes Simple, non-intentional, unlearned behaviors Pre-wired stimulus-response units Humans are born with a number of reflexes: Sucking reflex Moro reflex Knee-jerk reflex Eye-blink reflex Pupillary reflex Reflexive responses can be classically conditioned Contiguity and Reinforcement Contiguity: the simultaneous or nearly simultaneous occurrence of events for behavior to change (that is, for learning to occur), it is sufficient that two events be paired— sometimes only once, sometimes more often Reinforcement: a more complex concept having to do with the effects of a stimulus (e.g., positive reinforcement) Variations in Contiguity Contiguity ≠ Contingency Pavlovian conditioning is based on contiguity rather than contingency Variations in contiguity Simultaneous pairing: the CS starts and ends at exactly the same time as the US Delayed pairing: the CS is presented before the US and continues during presentation of the US Trace pairing: the CS starts and ends before the US so that there is a very brief time lapse between the two Backward pairing: the US has already been presented and removed before presentation of the CS Variations in Contiguity Impact of variations in CS-US procedures. The pairing sequences are shown here in the order of effectiveness. Conditioning takes place most quickly in the delayed sequence, when the conditioned stimulus (for instance, the buzzer) is presented shortly before the unconditioned stimulus (food powder) and continues throughout the time the US is presented. Backward Conditioning and Biological Predispositions Backward conditioning (backward pairing): long thought to be completely ineffective in an increasing number of experiments, investigators have succeeded in bringing about backward conditioning Biological predispositions: growing evidence that some types of learning are far easier for certain organisms than are other types Findings in Classical Conditioning Acquisition The formation of the stimulus-response association typically requires a number of pairings of CS and US. A hypothetical learning curve is portrayed to the right. Note that the strength of the conditioned response increases rapidly at first and then levels off. Learning curves are affected by the number of US-CS pairings and by the strength of the US. In general, the stronger the US, the more quickly the CR will reach its peak. Extinction and Recovery Classically conditioned responses can be eliminated—a procedure that Pavlov called extinction. One way to extinguish a conditioned response is to present the conditioned stimulus repeatedly without the unconditioned stimulus. However, if the CS is presented again later, the CR reoccurs, although at lower intensity—a phenomenon called spontaneous recovery. To completely extinguish the response, it would be necessary to present the CS without the US again— and perhaps to repeat the procedure a number of different times. A hypothetical representation of spontaneous recovery following extinction. Note how the strength of the CR is less following each extinction period, and how progressively fewer trials are required for extinction. Stimulus Generalization: making the same, or similar, responses when presented with any of a number of related stimuli Stimulus Discrimination: making different responses to related but distinctly different stimuli Higher Order Conditioning responses, stimuli, and reinforcers linked in complex ways Educational Implications of Classical Conditioning Classical conditioning, especially of emotional responses, occurs in all schools, at all times. Teachers need to do whatever they can to maximize the frequency, distinctiveness, and potency of pleasant unconditioned stimuli in their classrooms. Teachers need to try to minimize the unpleasant aspects of classroom learning to reduce the number and potency of negative unconditioned stimuli in their classrooms. Teachers need to know what is being paired with what in their classrooms. John Broadus Watson Founder of American behaviorism Worked his way through the University of Chicago graduate school as a rat caretaker At age 29, Watson was offered a full professorship at Johns Hopkins Edited one of the most influential publications in psychology, Psychological Review At age 36, became president of the American Psychological Association (APA) The study for which he is most famous involved the child, Little Albert Scandal forced his resignation from Johns Hopkins Became an advertising executive and vice president of the J. Walter Thompson Company Before his death in 1958, the APA honored him for his outstanding contributions to psychology Behaviorism Human actions, says can be understood through actual behaviors that can readily be observed and studied. Introspection forms no essential part of human psychological methods. Behavior consists of responses that can be observed and related to other observable events, such as conditions that precede and follow behavior. Behaviorists tried to limit psychology to the study of actual, observable behaviors. Watson’s Learning: A Classical Conditioning Explanation Humans are born with a number of reflexes Physical Emotional Reflexes can be brought about by specific stimuli Conditioned Emotional Reactions According to Watson, emotional behavior, like all other behavior, is simply another example of classical conditioning. All people are born with the same emotional reflexes (i.e., fear, love, rage, etc.). People acquire conditioned emotional reactions. Watson proposed to explain this important phenomenon using classical conditioning. Later emotional reactions, he explained, result from the pairing of initially neutral stimuli with stimuli that are associated with emotional responses. To illustrate this belief, Watson conducted his famous and controversial investigation: the study of Little Albert. Transfer: the making of similar responses for a variety of related stimuli. Emotional responses are conditioned to various stimuli as a result of pairings that occur between conditioned stimuli such as distinctive sounds, smells, sights, or tastes, and unconditioned stimuli such as those that produce fear or love or anger. Emotional responses can spread to stimuli to which they have not been conditioned, but that resemble conditioned stimuli. Positive Emotions It is possible to condition negative emotional reactions by repeatedly pairing a stimulus ordinarily associated with some negative emotion with another distinctive stimulus. It is also possible to condition positive emotional reactions to neutral stimuli. Counterconditioning can be used to reverse the associated reactions. Controversy with Watson’s Little Albert study N=1 Watson seemed unclear about what he did with Albert Some of Albert’s reactions could be attributed to not allowing Albert to suck his thumb Watson’s Environmentalism Nature – Nurture Controversy: Nature camp: Humans primarily a product of genetic makeup Nurture camp: Humans are molded and shaped mainly by their environment The controversy surrounding the relative roles of experience and heredity in shaping human development is far from resolved. Higher Learning All learning, said Watson, is a matter of responses that are selected and sequenced. More complex learning simply requires the conditioning of more stimulus-response sequences, eventually leading to what he called habits. Practical Applications of Watson’s Psychology Watson’s unwavering conviction that experiences determine all that people do and know leads logically to the belief that all humans are basically equal. The theory also lends itself to rigid prescriptions for child rearing and education, as well as for training and control in the military, in industry, and elsewhere. The theory fails to recognize differences among individuals, it insists that people’s behavior can be controlled through the judicious and clever arrangements of stimulus and response events Attitudes and Emotions Simple models of classical conditioning are very useful in explaining emotional learning. Many emotions appear to be learned as a result of an often-unconscious process of classical conditioning. Classical conditioning of a math phobia Behavior Modification In the same way as a phobia might be acquired through classical conditioning, it might also be removed using similar principles. The role of classical conditioning can be applied in learning (and unlearning) behaviors. An Appraisal of Watson’s Behaviorism Watson’s theory, which became immensely popular in the United States, had a profound influence on child-rearing and educational practices. Some critics contend that Watson was probably guilty of exaggerating the role of learning in determining behavior, and underemphasizing the role of heredity. Watson did much to make the science of psychology more rigorous and more objective. Watson popularized the notion that environmental experiences are potent forces in shaping behavior patterns. Watson elaborated a learning model (classical conditioning) that explains at least some aspects of animal and human behaviors. Edwin Ray Guthrie Born and raised in rural Nebraska Father owned a bicycle and piano shop; mother was a schoolteacher Guthrie was a high school teacher for three years His PhD. was in philosophy; however, his shift to psychology came in 1919 Watson was profoundly influenced by Pavlov’s classical conditioning He is known for his irreverent writing style filled with humor and anecdotes Dean of graduate studies at the University of Washington Was president of the American Psychological Association Guthrie’s Law of One-Shot Learning “A combination of stimuli which has accompanied a movement will on its recurrence tend to be followed by that movement” When an organism does something on one occasion, it will tend to do exactly the same thing if the occasion repeats itself. The full strength of the “bond” between a stimulus and a response is reached during the first pairing; it will neither be weakened nor strengthened by practice. What they learn is not a connection between two stimuli (as happens in Pavlovian classical conditioning), but a connection between a stimulus and a response. The Role of Practice and Repetition Note Guthrie’s use of the word ‘tend’ in his law The outcome of any one stimulus or stimulus pattern cannot be predicted with certainty because there are other stimulus patterns present, hence the tendency to repeat responses to particular stimuli Practice and repetition are valuable Practice provides an opportunity for making the same response in a wide variety of different situations The need for repetition comes from the need for executing the act in a variety of circumstances Movement Produced Stimuli A stimulus is not just one sensation but, rather, is a combination of numerous sensations. According to Guthrie, learning involves associating a response to a combination of stimuli. Similarly, a response is not just a single, final act; rather, it is a sequence of actions. To simplify, the sound of a bell leads to a number of alerting responses: turning the ears, moving the eyes, perhaps moving the head and neck, and so on. Every such motion is a stimulus to many sense organs in muscles, tendons, and joints, as well as the occasion for changing stimuli to eyes, ears, etc. Guthrie labeled these stimuli movement produced stimuli (MPS). Contiguity in MPS The sequence between the initial presentation of a stimulus and the occurrence of response is filled with a sequence of responses and the proprioceptive (internal) stimulation that results (MPS). Each of these responses and their corresponding MPS are in contiguity (occur at the same time), and so each becomes associated, or learned. These learned associations are what guide behavior. The entire sequence is learned because each individual MPS is present at the same time as the response occurs. One of the clearest examples of MPS is found in the learning of athletic skills, as these skills often consist of long sequences (or chains) of responses. Guthrie’s Law of One-Shot Learning Guthrie’s law of one-trial learning: “A combination of stimuli which has accompanied a movement will on its recurrence tend to be followed by that movement.” According to the theory, each overt response is accompanied by a series of stimuli produced by the movement (changes in the visual field, in bodily sensations, and so on). These movement produced stimuli (MPS) lead to a continuation of the overt action—or to a change of response. Each MPS and each response in the chain is sequential and overlapping in time (hence in contiguity). According to the theory, learning occurs through contiguity. Habits According to Guthrie, learning occurs in one trial, but this does not mean that a complex behavior can be learned in one trial. Each individual component of the vast number of stimulus-response associations that make up a complex act requires only a single pairing. A number of trials might be required, however, before all have been associated as they need to be. When they are all linked so that a particular combination of stimuli reliably leads to a particular combination of responses, what we have is a habit—a stereotyped, predictable pattern of responding. Humans are seldom completely predictable, and they do not respond exactly the same way every time they are placed in the same situation. Explanations: if responses to two stimuli are different, it’s because the stimuli are not exactly identical it may be that through one of a number of procedures, a new habit has replaced an old one. The old one is not forgotten—it is merely replaced Forgetting The best explanation for forgetting, says Guthrie, is not that associations are wiped out with the passage of time, but that time allows new learning to replace the old. It follows from the theory that whatever response was last performed in a stimulus situation will tend to be repeated again when that situation next arises. Reward and Punishment According to Guthrie, reward doesn’t do anything to strengthen the link between stimulus and response. But what it does is change the stimulus situation, thus preventing the animal (or person) from learning something different. Punishment, too, can change a stimulus situation and serve, in Guthrie’s words, to “sidetrack” a habit. Learning depends on contiguity (that is, on the simultaneity of stimulus and response events) to be effective, thus punishment has to occur during the response, or very soon afterward. Because punishment works by interrupting the unwanted habit, anything that grabs attention and brings about a different behavior will work. Practical Applications of Guthrie’s Theory One-shot theory of contiguity learning: to bring behavior under control, it is necessary to arrange for the behavior to occur in the presence of stimulus conditions that you control responses are never forgotten; they are merely replaced by more recently learned responses the best way of breaking a habit is to find the cues that initiate the habit and to practice another response to those same cues Three techniques for breaking habits Fatigue technique (flooding) involves presenting the stimulus repeatedly to elicit continued repetition of the undesired response. Eventually the organism will become so fatigued it can no longer perform the response. Threshold technique involves presenting the stimulus that forms part of the undesirable S-R (for stimulus-response) unit (habit) but presenting it so faintly that it doesn’t elicit the undesirable response. If it doesn’t elicit the undesirable behavior, then it probably elicits another response. Incompatible stimuli technique involves presenting the stimulus when the response can’t occur. Because the undesirable reaction is prevented, a different response takes its place and eventually replaces the old habit entirely. Guthrie’s Three Ways of Breaking Habits In (a) the horse is “broken” in the traditional sense, being allowed to buck until fatigued. In (b) the horse is “gentled” by having progressively heavier weights placed on its back, beginning with a blanket and culminating with a saddle and rider. In (c) the horse is tied down so it cannot buck when mounted. An Appraisal of Guthrie’s One-Shot Learning The theory is relatively simple and highly practical. Although the simplicity of the theory is one of its main attractions, it is also one of its weaknesses. The theory lacks the sort of detail required to make clear what concepts such as habits, movement produced stimuli, and, indeed, responses and stimuli are. In this theory, stimuli are what lead to responses; responses are what result from stimuli. Hence, these two variables, both of which are central to the theory, are defined only in terms of each other. Evaluation of Early Behavioristic Theories Pavlov, Watson, and Guthrie were concerned mainly with discovering and explaining regularities that underlie relationships among stimuli and responses. How good are these theories? they fit the facts reasonably well as the facts were known then they tend to be clear and understandable they are relatively parsimonious they are internally consistent their insistence on objectivity generally means that they are not based on many unverifiable assumptions their contributions to the subsequent development of learning theories can hardly be overestimated these theories have proven to be highly practical in a variety of applied situations they serve as important precursors of contemporary theories Weaknesses of these early behavioristic positions are that they largely ignored individual differences in ability as well as in preferred ways of learning