Conor O'Mahony Annual Conference 2014

advertisement

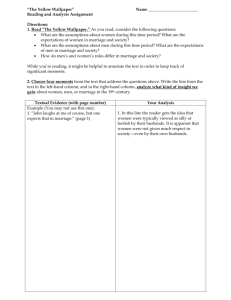

Marriage Equality and the Irish Constitution: Why are we having a Referendum? Dr Conor O’Mahony Senior Lecturer in Constitutional Law, UCC conor.omahony@ucc.ie @ConorUCCLaw Information Cascades Does the Constitution Permit Marriage Equality? “It is my strong belief, based on sound legal advice, that gay marriage would require constitutional change and in my view a referendum on this issue at this time would be divisive and unsuccessful and, furthermore, would jeopardise the progress we have made over the last 15 years” (Irish Times, December 2007) Does the Constitution Permit Marriage Equality? “There is common ground in our understanding of the Constitution that a constitutional referendum would be required to introduce the status of same-sex marriage.” (Dail Debates, January 2010) Does the Constitution Permit Marriage Equality? “The introduction of full civil marriage for the gay community would require a constitutional referendum, as has been indicated by other speakers. This is the advice of the AttorneyGeneral and our party’s legal advice.” (Dail Debates, January 2010) Does the Constitution Permit Marriage Equality? “…absolute and clear protection is given in Articles 40 and 41 to marriage as an act between persons of opposite sex. I am not saying that in the future that could not change. However, the only way it could change is if there is a referendum.” (Dail Debates, January 27 2010) Does the Constitution Permit Marriage Equality? • Article 41 of Irish Constitution & Zappone and Gilligan v Revenue Commissioners (2006) • Almost universally assumed to preclude marriage equality – but do they??? What does the Constitution say about Marriage? • Article 41.3: “The State pledges to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, on which the Family is founded, and to protect it against attack.” • Marriage not defined • Clearly understood as opposite-sex when drafted in 1937 but original intent is not decisive What have the courts said? • Walsh J, McGee v Attorney General (1974): • “… no interpretation of the Constitution is intended to final for all time. It is given in the light of prevailing ideas and concepts.” • Quoted with approval by Dunne J in Zappone and Gilligan • So is “Marriage” in Art 41.3 to be defined by present-day ideas and concepts? What have the courts said? • Confusion in Zappone and Gilligan decision • Dunne J distinguished between “ascertaining unenumerated rights and redefining a right which is implicit in the Constitution and which is clearly understood” • Held she had “a difficulty in this case in accepting the arguments of the plaintiffs to the effect that the definition of marriage as understood in 1937 requires to be reconsidered in the light of now prevailing standards and conditions.” What have the courts said? • “How then can it be argued that in the light of prevailing ideas and concepts that definition be changed to encompass same sex marriage? ... as recently as 2004, s. 2(2)(e) of the Civil Registration Act was enacted. That Act sets out what was previously the common law exclusion of same sex couples from the institution of marriage. Is that not of itself an indication of the prevailing idea and concept in relation to what marriage is and how it should be defined? I think it is.” What have the courts said? Dunne J accepted “living constitution” doctrine She then suggested that current consensus was irrelevant to definition of marriage (authority she cited did not support this point) She then examined current consensus anyway, and used it to define marriage as opposite-sex only What have the courts said? • At best, Zappone and Gilligan is ambiguous and contradictory • Better view is probably that definition of marriage is to be determined by current consensus • Two passages from Zappone and multiple other authorities support this conclusion • One passage suggests otherwise, but is not supported by the authority it cites Who gets to decide? • If provisions of Constitution are defined by reference to current consensus – who gets to decide what that consensus is? • The courts could decide – but difficulties with democratic legitimacy and institutional competence • The Oireachtas is better placed to represent the views of society Who gets to decide? • Dunne J cited the Civil Registration Act 2004 as evidence of consensus at the time • If a “Marriage Equality Act” were enacted in 2014 – that would represent consensus today • Open to challenge in the courts – but who would have standing to bring challenge? • Why should the courts not defer to legislature’s assessment of consensus? Law and Politics • Referendum not legally necessary • Political situation has made it so • TDs unwilling to legislate without referendum • Matter referred to Constitutional Convention • Public think a referendum is necessary and expect one to happen • Legislating without referendum no longer politically feasible • Court decision potentially damaging – potential for Proposition 8-style backlash Disadvantages of Referendum • Unusual way to advance minority rights claims • “[F]undamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.” (Justice Jackson) • No filter on tone of debate • Easier for citizens than for politicians to base vote on prejudice or animus • US experience: marriage equality lost 30 referendums in a row • May be difficult to secure a second shot if it fails Advantages of Referendum • Durability – successful outcome unlikely to be reversed • Legitimacy – harder for losers to claim they didn’t get a fair fight • Shot at history: 3 US States recently approved marriage equality by referendum – but no country in the world has done so by national referendum • Ireland could be a world leader on a key equality and human right issue Further Reading • O’Mahony, “Principled Expediency: How the Irish Courts Can Compromise on Same-Sex Marriage” (2012) 35 Dublin University Law Journal 199, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2321595 • O’Mahony, “If a Constitution is Easy to Amend, Can Judges be Less Restrained? Rights, Social Change and Proposition 8” (2014) 27 Harvard Human Rights Journal (forthcoming at www.harvardhrj.com)