Sexual Minority Youth in Out-of-Home Settings: State of the

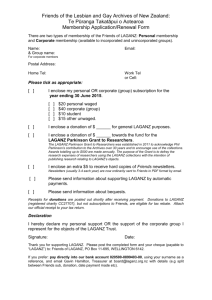

advertisement

Sexual Minority Youth in Out-of-Home Settings: State of the Literature and Future Directions Adam Leonard, MSW/MPH Student Colleen Fisher, Ph.D. University of Minnesota School of Social Work Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare Key Terms • Sexual Minority: Person who identifies as non-heterosexual • GLBTQ: Gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or questioning sexual orientation What We Know About GLBTQ Youth in Out-of-Home Settings • An “invisible” population; very little empirical research 1 • Much of what we know comes from just a few samples of youth • Existing research primarily focused on practice guidelines for workers and policy suggestions for child welfare organizations Sexual Identity Development among Sexual Minority Youth Sexual identity development (SID) is an ongoing process that generally includes the following milestones: 19 • same-sex and/or opposite-sex sexual attraction (SSA/OSA) • same-sex and/or opposite-sex sexual experience (SSC/OSC) • self-labeling as non-heterosexual (SL) • disclosure to others (D) SSA D OSA SL SSC OSC Sexual Identity Development Among Sexual Minority Youth (cont’d) The SID process includes important contextual factors including: • It is not a linear process; some youth follow different sequential order of milestones over time while others experience multiple milestones in close order 19, 20, 27 • It is an ongoing process; many youth will change their self-label over time and chose to disclose to different people at different times 21, 22, 27 • Because of fear of family rejection, many young people will first disclose to a friend or other “safe person” rather than a parent 21 • The context of this process can have negative health impacts, including risky sexual behavior, mental health problems, suicidal ideation, and increased substance use 23, 24,25, 26 Sexual Identity Development as a Non-Linear Process • The process of self-labeling one’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity is on-going during a young person’s development • As youth continually discover and define their sexual and gender identity, they may have multiple instances of selflabeling as a sexual minority or transgender person • The following slide graphically illustrates the history of multiple self-labels (SL1, SL2, SL3) and gender-identity self-labels (GSL) among a sample of youth • Note how some youth experience multiple labels in short spans of time while other youth experience them over many years (red arrows illustrate long time periods between different selflabels; circles indicate a quick change in self-label) Example of Multiple Self-Label (SL) Milestones for Sexual Minority Youth 27 16 15 14 13 12 PARTICIPANT 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 AGE 12 13 14 SL 15 16 SL2 17 18 SL3 19 20 21 GSL GLBTQ Youth’s Experiences in the Child Welfare System While many sexual minority youth in out-of-home care report positive encounters with the child welfare system, many others report a range of negative experiences,1, 4 including: • Verbal harassment and victimization 5, 6 • Inadequate care, exposure to reparative therapy and abuse by homophobic foster parents 5, 7 • Child welfare staff who often fail to act on or participate in harassment and abuse 5, 6, 8 • Multiple and unstable placements and lack of positive permanency outcomes 9, 10, 11 Pathways to the Child Welfare System for GLBTQ Youth (2) Disclosure or discovery of sexual identity or gender identity leads to rejection from family of origin.2 (1) Same as straight youth, then later become aware of their sexual minority identity while still in state custody.2, 3 (3) Chronic truancy issues resulting from harassment & victimization at school based on their sexual or gender identity.3 Child Welfare System (4) Verbal, emotional & physical abuse lead many GLBT youth to live on the streets rather than remaining with unsupportive & abusive adults.3 (5) Youth may be erroneously labeled as sexual offenders for engaging in consensual same-sex conduct .3 The Child Welfare & Homelessness Connection For some youth, homelessness is both an experience that leads to and results from involvement with the child welfare system • In one study, 26% of families whose children were in outof-home care experienced eviction, 42% reported living in a doubled-up situation, and 29% reported experiencing homelessness 12 • In 1997, nearly two-thirds of all young people accessing federally funded youth shelters had been in the foster care system 13 Health & Psychosocial Risks for GLBTQ Homeless Youth Compared to their heterosexual homeless counterparts, GLBTQ homeless youth are more likely to: • Use alcohol and illegal substances, including Injection Drug Use (IDU) 14 • Report suicidal ideation and suicide attempts 15 • Experience mental health problems and specific risk of conditions associated with both internalizing and externalizing behaviors 16 • Experience physical abuse and sexual assault while living on the street 17 Health & Psychosocial Risks for GLBTQ Homeless Youth (cont’d) Compared to their heterosexual homeless counterparts, GLBTQ homeless youth are more likely to: • Engage in high risk sexual behaviors than increase STI and HIV infection rates 16 • Report participating in non-sexual criminal behavior to survive 17 • Participate in exchange sex (trading sex for food, money, shelter, drugs or other resources) as a survival strategy 18 Recommendations The following are recommendations for • Child welfare researchers • Foster parents and other caregivers • Child welfare workers & professionals Recommendations for Child Welfare Researchers • Continued and improved research on GLBTQ youth in out-ofhome care as it relates to: service needs, experiences in the system, and long-term outcomes • New studies utilizing larger and more geographically diverse samples, longitudinal designs when possible, and innovate assessment tools such as the Life History Calendar (see next slide) • Exploring different ways to document the experiences of GLBTQ youth suggests that tools like the Life History Calendar can help researchers learn important information about the needs of this population Excerpt of Sample Life History Calendar for GLBTQ Out-of-Home Youth 27 Calendar Year Month Age / Birthday Semester Year in School LANDMARKS 2007 2008 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Spring Holidays & Celebrations Jobs or other FAMILY & LIVING SITUATION Living situation CW experiences Important Relationships SEXUAL IDENTITY MILESTONES 1st Female Attraction 1st Male Attraction 1st Female Sexual Contact 1st Male Sexual Contact 1st Self-label Other Self-label 1st Disclosure Other Disclosure Sum Fall Spring Sum Fall Recommendations for Foster Parents & Other Care Givers • Receive comprehensive training on sexual identity development and how it influences the needs of sexual minority youth in out-of-home care • Undergo ongoing training and evaluation of compliance with agency policies and guidelines as it pertains to creating supportive environments for GLBTQ youth free from discrimination and violence Recommendations for Child Welfare Workers & Professionals • Partner with homeless youth organizations and GLBTQ advocacy organizations to institute trainings and practices that enable service delivery and system design to be GLBTQ-affirming • Pay special attention to the unique needs of these youth as they pertain to permanency planning and aging out of care in an effort to better prevent homelessness and improve the transition to independence Recommendations for Child Welfare Workers & Professionals (cont’d) • Ensure that all foster parents, direct care staff and other providers are adequately trained in the experiences of GLBTQ youth and what the agency guidelines are for appropriate and quality care • Monitor the placements of sexual minority youth to safeguard against sexual orientation or gender identity based discrimination, paying particular attention to foster parent’s beliefs about GLBTQ youth and boundaries around religious proselytizing in the home Summary of Research & Recommendations • GLBTQ youth are an often overlooked population within the Child Welfare System • The sexual identity development process for GLBTQ youth is on-going and should be continually assessed to inform case planning • Some GLBTQ youth enter the child welfare system because of events unrelated to their sexual orientation or gender identity • Other youth enter out-of-home care because of stress, violence and instability associated with parental rejection of their sexual minority status Summary of Research & Recommendations (cont’d) • Sexual minority youth in out-of-home care have unique experiences that require special attention by child welfare professionals • Specifically, GLBTQ youth report experiencing sexualorientation and/or gender-identity motivated bias on the part of other youth, foster parents or care givers, and child welfare workers while in out-of-home care • These experiences contribute to multiple and unstable placements and can affect permanency planning Summary of Research & Recommendations (cont’d) • GLBTQ youth in out-of-home care often have experiences with homelessness, either before involvement with the child welfare system or after it • Sexual minority youth who are homeless are at increased risk for a variety of physical and mental health problems, drug use and criminal activity as a survival tool • People in the child welfare field need to be adequately trained on GLBTQ youth’s unique service needs and take active steps to ensure safe and supportive placements for this population Additional Resources • The Family Acceptance Project – http://familyproject.sfsu.edu/ • Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) – http://www.glsen.org • Gender Spectrum Education and Training – http://www.genderspectrum.org/ • Child Welfare League of America, GLBTQ Practice Guidelines – http://www.cwla.org/programs/culture/glbtqpubs.htm References 1 Mallon, G. P., Aledort, N., & Ferrera, M. (2002). There's no place like home: Achieving safety, permanency, and well-being for lesbian and gay adolescents in out-of-home care settings. Child Welfare Journal, 81(2), 407-439. 2 Mallon, G. P. (1998). We don’t exactly get the welcome wagon: The experiences of gay and lesbian adolescents in the child welfare system. New York: Columbia University Press. 3 Wilber, S., Ryan, C., & Marksamer, J. (2006). CWLA best practices guidelines: Serving LGBT youth in out-of-home care. Arlington, VA: Child Welfare League of America. 4 Mallon, G. P. (1997). Basic premises, guiding principles, and competent practices for a positive youth development approach to working with gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths in out-of home care. Child Welfare, 76(5), 591-609. 5 Craig-Oldsen, H., Craig, J. A., & Morton, T. (2006). Issues of shared parenting of LGBTQ children and youth in foster care: Preparing foster parents for new roles. Child Welfare Journal, 85(2), 267-280. 6 Freundlich, M., & Avery, R. J. (2004). Gay and lesbian youth in foster care: Meeting their placement and service needs. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: Issues in Practice, Policy & Research, 17(4), 3957. 7 Clements, J. A., & Rosenwald, M. (2007). Foster parents' perspectives on LGB youth in the child welfare system. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: Issues in Practice, Policy & Research, 19(1), 57-69. 8 Ragg, D. M., Patrick, D., & Ziefert, M. (2006). Slamming the closet door: Working with gay and lesbian youth in care. Child Welfare, 85(2), 243-265. 9 Sullivan, T. R. (1994). Obstacles to effective child welfare service with gay and lesbian youths. Child Welfare, 73(4), 291-304. References (cont’d) 10 Wilber, S., Reyes, C., & Marksamer, J. (2006). The model standards project: Creating inclusive systems for LGBT youth in out-of-home care. Child Welfare Journal, 85(2), 133-194. 11 Jacobs, J., & Freundlich, M. (2006). Achieving permanency for LGBTQ youth. Child Welfare Journal, 85(2), 299-316. 12 Courtney, M. E., McMurtry, S. L., & Zinn, A. (2004). Housing problems experienced by recipients of child welfare services. Child Welfare Journal, 83(5), 393-422. 13 National Coalition for the Homeless (1998, September-October). Breaking the Foster Care Homelessness Connection. Safety Network: The Newsletter of the National Coalition for the Homeless. 14 Van Leeuwen, J. M., Boyle, S., SalomonsenSautel, S., Baker, D. N., Garcia, J. T., Hoffman, A., et al. (2006). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual homeless youth: An eight-city public health perspective. Child Welfare Journal, 85(2), 151-170. 15 Noell, J. W., & Ochs, L. M. (2001). Relationship of sexual orientation to substance use, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and other factors in a population of homeless adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29(1), 31-36. 16 Cochran, B. N., Stewart, A. J., Ginzler, J. A., & Cauce, A. M. (2002). Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: Comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 773-777. 17 Whitbeck, L. B., Chen, X., Hoyt, D. R., Tyler, K. A., & Johnson, K. D. (2004). Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 41(4), 329-342. 18 Gangamma, R., Slesnick, N., Toviessi, P., & Serovich, J. (2008). Comparison of HIV risks among gay, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual homeless youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(4), 456-464. References (cont’d) 19 Maguen, S., Floyd, F. J., Bakeman, R., & Armistead, L. (2002). Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 219-233. 20 Savin-Williams, R. C., & Diamond, L. M. (2000). Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(6), 607-627. 21 D'Augelli, A. R., Hershberger, S. L., & Pilkington, N. W. (1998). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 361-71; discussion 372-5. 22 Remafedi, G., Resnick, M., Blum, R., & Harris, L. (1992). Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics, 89(4 Pt 2), 714-721. 23 D'Augelli, A. R. (2003). Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: Developmental challenges and victimization experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7(4), 9-29. 24 D'Augelli, A. R., Hershberger, S. L., & Pilkington, N. W. (2001). Suicidality patterns and sexual orientation-related factors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(3), 250-264. 25 Rostosky, S. S., Danner, F., & Riggle, E. D. (2007). Is religiosity a protective factor against substance use in young adulthood? only if you're straight!. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(5), 440-447. 26 Wright, E. R., & Perry, B. L. (2006). Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(1), 81-110. 27 Fisher, C. (2008). Capturing the complexities of sexual identity development and HIV risk: Use of the Life History Calendar with sexual minority youth. Paper presented at the 136th Annual Meeting and Expo of the American Public Health Association, San Diego, CA (October 29, 2008).