Chinese Exclusion Act

advertisement

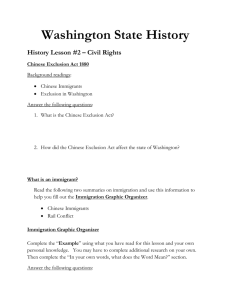

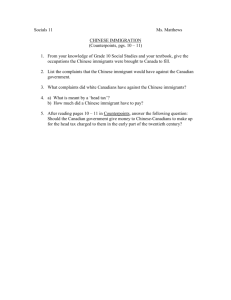

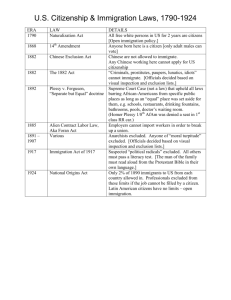

Lesson Plan: Anti-Asian sentiment of the west coast during the late 1800’s Lesson designer (s): Marcie Gorsuch School: Harrison High Lesson Origin: (web site, modified from, original) http://sun.menloschool.org/~mbrody/ushistory/angel/exclusion_act/ DIGITAL HISTORY : Hypertext: Guided Readings: The Huddled Masses The Statue of Liberty Emma Lazarus The New Immigrants Birds of Passage Chinese Exclusion Act Angel Island Japanese Immigration Contract Labor Immigration Restriction Migration and Disease http://stories.washingtonhistory.org/Railroads/Teaching/MiddleSchool.aspx Georgia Performance Standard: SSUSH14 The student will explain America’s evolving relationship with the world at the turn of the twentieth century. a. Explain the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and anti-Asian immigration sentiment on the west coast. Essential Question: (Learning Question) Who was involved in the expulsion of Chinese people from the US? What motivations did they have? Were they economic, political, social? What kind of effect did the Chinese Exclusion Act have on the people it targeted? OPTIONAL: RELATE TO CURRENT EVENTS AS TIME ALLOWS How does this topic relate to us today? What is the role of the United States government in regard to immigration? What issues are the same as they were in the 1880’s and what issues have changed? Why is this topic important? Compare and contrast the U.S. federal government’s policy towards Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans during the late 1800’s. Materials: (include at least one primary source) Background reading on Chinese Exclusion Act Guided readings from Digital History Common Core Historical Literacy Standards/Skills (LDC Module) CCRR12 - Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas. What Task? Students will examine a series of textual resources as well as a few cartoons related to antiAsian sentiment as it applies to American 19th century history. They will have a series of questions to use as prompts. What Skills? Students will determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary skills. What Instruction? Students will be given 3-4 different sources to read related to the topic and will have to identify themes, details and ideas. What results? Students will provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships among the key details and ideas. Technology use (include I-Respond file if used): Digital History website for guided readings Suggestions for differentiation/modification: Use the Venn diagram as the end product for regular level students and a completed argumentative Documents Based Essay for the higher level students. Extensions (advanced students): Document Based Essay: Evaluate the U.S. federal government’s policy towards Chinese Americans during the late 1800’s. Depth of Knowledge level: Analysis and synthesis will be required as well as identification of supporting details related to the topic. Students will be taking an AP exam and so will need to identify and evaluation America’s policy towards. Modeling/Guided Practice/Independent Practice elements: The teacher will use the reading entitled Migration and Disease as a modeling exercise from Digital history. The two questions given at the end of the reading will serve as same prompts for the students. They will be asked to identify their own investigative type questions that could be used in addition to the original two given. Elements of Teaching American History Grant activities incorporated into the lesson: Sourcing - Specifically with the cartoons and interview, students will be expected to think about what the author’s intention and message would be. Who would support or appreciate the cartoon? Why did the author create it? Contextualization – Students will need to consider the location ( west coast) and situation in time of the documents and cartoons. Each document will need the reader to consider the dates and visualize what was happening during this time period that led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Close Reading – Students will need to use this when reading the guided readings and information related to the Chinese Exclusion Act. Students will need to consider what each source identifies as motivation for the anti Asian policies. Also, students should be attentive to the descriptions and stereotypes associated with the Chinese. Corroboration – Students will use the essential questions given in the lesson to identify motivations and effects of the Anti Asian sentiment as it resulted in the exclusion and discrimination aimed at the Chinese in 19th century America. 1. 2. The Chinese Exclusion Act: A Black Legacyhttp://sun.menloschool.org/~mbrody/ushistory/angel/exclusion_act/ Passed in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was a climax to more than thirty years of progressive racism. Anti-Chinese sentiment had existed ever since the great migration from China during the gold rush, where white miners and prospectors imposed taxes and laws to inhibit the Chinese fr Racial tensions finally snapped in 1882, and Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, barring immigration for ten years; the Geary Act extended the act for another ten years in 1892, and by the Extension Act of1904, the act was made permanent. Racial tensions finally snapped in 1882, and Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, barring immigration for ten years; the Geary Act extended the act for another ten years in 1892, and by the Extension Act of1904, the act was made permanent. created competition on the job market. By 1882 the Chinese were hated enough to be banned from immigrating; the Chinese Exclusion Act, initially only a ten year policy, was extended indefinitely, and made permanent in 1902. The Chinese resented the idea that they were being discriminated against, but for the most part they remained quiet. In 1943, China was an important ally of the United States against Japan, so the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed; however, a lasting impact remained. The act was both cause and effect: it came from decades of Chinese discrimination, and initiated decades of Chinese exclusion. The Chinese flocked to America in search of opportunities; most fled from their collapsing empire for economic reasons. The Gold Rush happened during a period of poverty in China, which both pushed and pulled the Chinese to emigrate. In California, the Chinese newcomers soon became an exploited work force, especially since they were predominantly male, but the wages they received in the burgeoning 1850's economy were still "considerably higher than they could earn at home" (Daniels 15). Many Chinese became miners, and some developed the laundry business (highly lucrative in overpopulated San Francisco). But opposition in California was both immediate and strong. During the Gold Rush, thousands of Americans from the East, where they had opposed European immigration, frequently came with nativist attitudes. And non-American whites (Irish, Russian), who had suffered from Eastern nativism, saw that in attacking the Chinese, they elevated their own (shaky) status. Thus, Chinese immigrants faced discrimination from many different groups, including American miners, who felt that the hard-working and low-paid Chinese were reducing their wages. It is the duty of the miners to take the matter into their own hands and erect such barriers as shall be sufficient to check this asiatic inundation The Capitalists who are encouraging or engaged in the importation of these burlesques on humanity would crown their ships with the long tailed, horned and cloven-hoofed inhabitants of the infernal regions if they could make a profit on it. (McLeod, qtd. in Daniels, 34) Thus, during the financially unstable 1870's, the Chinese became an ideal scapegoat: they were strangers, wore queues, kept to their own kind, and were very productive (conditions not inspiring great love, especially among the American laboring class). Legislation, including immigration taxes, and laundry-operation fees, passed in order to limit the success of the Chinese workers. Cartoons and other propaganda reinforced the view that the Chinese "worked cheap and smelled bad" (Daniels 52); demonstrators marched with anti-Chinese slogans. WE WANT NO SLAVES OR ARISTOCRATS THE COOLIE LABOR SYSTEM LEAVES US NO ALTERNATIVE STARVATION OR DISGRACE 3. MARK THE MAN WHO WOULD CRUSH US TO THE LEVEL OF THE MONGOLIAN SLAVE WE ALL VOTE WOMEN'S RIGHTS AND NO MORE CHINESE CHAMBERMAIDS (Daniels, 38) 4. "A Statue for Our Harbor" Courtesy of: Choy, Philip. Dong, Lorraine. Hom, Marlon. The Coming Man. University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 1994. Page:136 5. "The Last Load" Courtesy of:Choy, Philip. Dong, Lorraine. Hom, Marlon. The Coming Man. University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 1994. Page:157 But immigration still went on; however, as the exclusion laws were frequently bypassed. After the earthquake fires destroyed all family records in 1906, Chinese immigrants effectively donned false names and identities, and came to their "relatives" already in the US as paper sons and daughters. In response to this continuing Chinese influx, the city of San Francisco created a prison-like detention center for incoming immigrants at Angel Island in 1910, where officials screened and deported dubious incomers. Americans justified their actions with two main claims. First, the Americans claimed that jobs were scarce, and the Chinese were stealing the only jobs that there were because of there willingness to work for smaller wages. Americans also claimed that the Chinese were sending too much gold back to China-they believed that the wealth should remain within the United States (Knoll 24). Anti-sentiments against the Chinese were high in the United States, however, Chinese continued to immigrate to the United States. Not only was the majority of Chinese excluded from immigrating, however, the few Chinese that did immigrate were treated inhumanely. Many of their customs and traditions were violated, they were insulted, they were imprisoned, beat and in some cases killed. Why did we have to depart from our parents and loved ones and come to stay in a place far away from our homes? It is for no reason but to make a living. In order to make a living here, we have to endure all year around drudgery and all kinds of hardship. We are in a state of seeking shelter under another person's face, at the threat of being driven away at any moment. We have to swallow down the insults hurled at us. (Knoll, 28) The Chinese resented the fact that they were being discriminated against, yet they continued to immigrate to the United States because they felt their opportunities in the United States were still better than in China. For sixty-one years, the Chinese were excluded from entering the United States and becoming natural citizens when on December 17, 1943, the United States Congress pass the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act, which allowed Chinese to enter the United States legally once again. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed mainly for political reasons rather than for human rights reasons. The main political reason was that the Chinese became an ally of the United States extremely fast when World War II broke out. Since the Chinese were viewed as allies now, the American government wanted to keep sentiments between the two countries high, so the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed, and Angel Island no longer remained a detainment center for Chinese immigrants. This was a victory for people from China and ChineseAmericans; however, the American reputation remains tainted by its inhumane and racist exclusion policies towards the Chinese in the latter part of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century. Bibliography: BOOKS: Choy, Philip. Dong, Lorraine. Hom, Marlon. The Coming Man. University of Washington Press: Seattle and London, 1994. Daniels, Roger. Asian America. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988. Jones, Maldwyn Allen. American Immigration. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1960. Knoll, Tricia. Becoming Americans. Coast to Coast Books: Portland, 1982 6. 7. The Huddled Masses Chinese Exclusion Act Period: 1880-1920 From 1882 until 1943, most Chinese immigrants were barred from entering the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the nation's first law to ban immigration by race or nationality. All Chinese people--except travelers, merchants, teachers, students, and those born in the United States--were barred from entering the country. Federal law prohibited Chinese residents, no matter how long they had legally worked in the United States, from becoming naturalized citizens. From 1850 to 1865, political and religious rebellions within China left 30 million dead and the country's economy in a state of collapse. Meanwhile, the canning, timber, mining, and railroad industries on the United States's West Coast needed workers. Chinese business owners also wanted immigrants to staff their laundries, restaurants, and small factories. Smugglers transported people from southern China to Hong Kong, where they were transferred onto passenger steamers bound for Victoria, British Columbia. From Victoria, many immigrants crossed into the United States in small boats at night. Others crossed by land. The Geary Act, passed in 1892, required Chinese aliens to carry a residence certificate with them at all times upon penalty of deportation. Immigration officials and police officers conducted spot checks in canneries, mines, and lodging houses and demanded that every Chinese person show these residence certificates. Due to intense anti-Chinese discrimination, many merchants' families remained in China while husbands and fathers worked in the United States. Since Federal law allowed merchants who returned to China to register two children to come to the United States, men who were legally in the United States might sell their testimony so that an unrelated child could be sponsored for entry. To pass official interrogations, immigrants were forced to memorize coaching books which contained very specific pieces of information, such as how many water buffalo there were in a particular village. So intense was the fear of being deported that many "paper sons" kept their false names all their lives. The U.S. government only gave amnesty to these "paper families" in the 1950s. Copyright 2006 Digital History Japanese Immigration Period: 1880-1920 Overpopulation and rural poverty led many Japanese to emigrate to the United States, where they confronted intense racial prejudice. In California, the legislature imposed limits on Japanese land ownership, and the Hearst newspaper ran headlines such as 'The Yellow Peril: How Japanese Crowd out the White Race.' The San Francisco School Board stirred an international incident in 1906 when it segregated Japanese students in an 'Oriental School.' The Japanese government protested to President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt negotiated a 'gentlemen's agreement' restricting Japanese emigration. Contract Labor Period: 1880-1920 During the 19th century, demand for manual laborers to build railroads, raise sugar on Pacific Islands, mine precious metals, construct irrigation canals, and perform other forms of heavy labor, grew. Particularly in tropical or semi-tropical regions, this demand for manual labor was met by indentured or contract workers. Nominally free, these laborers served under contracts of indenture which required them to work for a period of time--usually five to seven years--in return for their travel expenses and maintenance. In exchange for nine hours of labor a day, six days a week, indentured servants received a small salary as well as clothing, shelter, food, and medical care. An alternative to the indenture system was the "credit ticket system." A broker advanced the cost of passage and workers repaid the loan plus interest out of their earnings. The ticket system was widely used by Chinese migrants to the United States. Beginning in the 1840s, about 380,000 Chinese laborers migrated to the U.S. mainland and 46,000 to Hawaii. Between 1885 and 1924, some 200,000 Japanese workers went to Hawaii and 180,000 to the U.S. mainland. Indentured laborers are sometimes derogatorily referred to as "coolies." Today, this term carries negative connotations of passivity and submissiveness, but originally it was an Anglicization of a Chinese work that refers to manual workers impressed into service by force or deception. In fact, indentured labor was frequently acquired through deceptive practices and even violence. Between 1830 and 1920, about 1.5 million indentured laborers were recruited from India, one million from Japan, and half a million from China. Tens of thousands of free Africans and Pacific Islanders also served as indentured workers. The first Indian indentured laborers were imported into Mauritius, an island in the Indian Ocean, in 1830. Following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1833, tens of thousands of Indians, Chinese, and Africans were brought to the British Caribbean. After France abolished slavery in 1848, its colonies imported 80,000 Indian laborers and 19,000 Africans. Also ending slavery in 1848, Dutch Guiana recruited 57,000 Asian workers for its plantations. Although slavery was not abolished in Cuba until 1886, the rising costs of slaves led plantations to recruit 138,000 indentured laborers from China between 1847 and 1873. Areas that had never relied on slave labor also imported indentured workers. After 1850, American planters in Hawaii recruited labor from China and Japan. British planters in Natal in southern Africa recruited Indian laborers and those in Queensland in northeastern Australia imported laborers from neighboring South Pacific Islands. Other indentured laborers toiled in East Africa, on Pacific Islands such as Fiji, and in Chile, where they gathered bird droppings known as guano for fertilizer. Steam transportation allowed Europeans and their descendants to extract "surplus" labor from overpopulated areas suffering from poverty and social and economic dislocation. In India, the roots of migration included unemployment, famine, demise of traditional industries, and the demand for cash payment of rents. In China, a society with a long history of longdistance migration, causes of migration included overpopulation, drought, floods, and political turmoil, culminating in the British Opium Wars (18391842 and 1856 and 1860) and the Taiping Rebellion, which may have cost 20 to 30 million lives. Overwhelmingly male, many indentured workers initially thought of themselves as sojourners who would reside temporarily in the new society. In the end, however, many indentured laborers remained in the regions where they worked. As a result, the descendents of indentured laborers make up a third of the population in British Guiana, Fiji, and Trinidad by the early 20th century. Some societies, such as the United States, passed legislation that hindered the migration of Asian women. In contrast, the British Caribbean colonies required 40 women to be recruited for every 100 men to promote family life. Copyright 2006 Digital History Immigration Restriction Period: 1880-1920 Gradually during the late 19th and early 20th century, the United States imposed additional restrictions on immigration. In 1882, excluded people were likely to become public charges. It subsequently prohibited the immigration of contract laborers (1885) and illiterates (1917), and all Asian immigrants (except for Filipinos, who were U.S. nationals) (1917). Other acts restricted the entry of certain criminals, people who were considered immoral, those suffering from certain diseases, and paupers. Under the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907-1908, the Japanese government agreed to limit passports issued to Japanese in order to permit wives to enter the United States; and in 1917, the United States barred all Asian immigrants except for Filipinos, who were U.S. nationals. Intolerance toward immigrants from southern and eastern Europe resulted in the Immigration Act of 1924, which placed a numerical cap on immigration and instituted a deliberately discriminatory system of national quotas. In 1965, the United States adopted a new immigration law which ended the quota system. During the 20th century, all advanced countries imposed restrictions on the entry of immigrants. A variety of factors encouraged immigration restriction. These include a concern about the impact of immigration on the economic well-being of a country's workforce as well as anxiety about the feasibility of assimilating immigrants of diverse ethnic and cultural origins. Especially following World War I and World War II, countries expressed concern that foreign immigrants might threaten national security by introducing alien ideologies. It is only in the 20th century that governments became capable of effectively enforcing immigration restrictions. Before the 20th century, Russia was the only major European country to enforce a system of passports and travel regulations. During and after World War I, however, many western countries adopted systems of passports and border controls as well as more restrictive immigration laws. The Russian Revolution prompted fear of foreign radicalism exacerbated by the Russian Revolution, while many countries feared that their societies would be overwhelmed by a postwar surge of refugees. Among the first societies to adopt restrictive immigration policies were Europe's overseas colonies. Apart from prohibitions on the slave trade, many of the earliest immigration restrictions were aimed at Asian immigrants. The United States imposed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. It barred the entry of Chinese laborers and established stringent conditions under which Chinese merchants and their families could enter. Canada also imposed restrictions on Chinese immigration. It imposed a "head" tax (which was $500 in 1904) and required migrants to arrive by a "continuous voyage." Xenophobia: Hatred of foreigners and immigrants Nativism: The policy of keeping a society ethnically homogenous. Copyright 2006 Digital History8. 8. Wong Tung Jim Interrogation, 1928. Testimony of Wong Tung Jim (Jimmie Howe), page 1, December 29, 1928, Chinese Exclusion Act immigration case files, Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group 85, National Archives-Pacific Alaska Region (Seattle), Case 29160, ARC Identifier 298955. 9. “The Chinese Question" February 18, 1871 Thomas Nast Modeling assignment. Migration and Disease Period: 1880-1920 Throughout history, the movement of people has played a critical role in the transmission of infectious disease. As a result of migration, trade, and war, disease germs have traveled from one environment to others. As intercultural contact has increased--as growing numbers of people traveled longer distances to more diverse destinations--the transmission of infectious diseases has increased as well. No part of the globe has been immune from this process of disease transmission. In the 1330s, bubonic plague spread from central Asia to China, India, and the Middle East. In 1347, merchants from Genoa and Venice carried the plague to Mediterranean ports. The African slave trade carried yellow fever, hookworm, and African versions of malaria into the New World. During the early 19th century, cholera spread from northeast India to Ceylon, Afghanistan and Nepal. By 1826, the disease had reached the Arabian Peninsula, the eastern coast of Africa, Burma, China, Japan, Java, Poland, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey. Austria, Germany, Poland, and Sweden were struck by the disease by 1829, and within two more years, cholera had reached the British Isles. In 1832, the disease arrived in Canada and the United States. Epidemic diseases have had far-reaching social consequences. The most devastating pandemic of the 20th century, the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918 and 1919, killed well over 20 million people around the world--many more people than died in combat in World War I. Resulting in such complications as pneumonia, bronchitis and heart problems, the Spanish Flu had particularly devastating impact in Australia, Canada, China, India, Persia, South Africa, and the United States. Today, the long-distance transfer of disease continues, evident, most strikingly with AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome), which many researchers suspect originated in sub-Saharan Africa. Disease played a critically important role in the success of European colonialism. After 1492, Europeans carried diphtheria, influenza, measles, mumps, scarlet fever, smallpox, tertian malaria, typhoid, typhus, and yellow fever to the New World, reducing the size of the indigenous population 50 to 90 percent. Measles killed one fifth of Hawaii's people during the 1850s and a similar proportion of Fiji's indigenous population in the 1870s. Influenza flu, measles, smallpox, whooping cough reduced the Maoris population of New Zealand from about 100,000 in 1840 to 40,000 in 1860. Fear of contagious diseases assisted nativists in the United States in their efforts to restrict foreign immigration. The 1890s was a decade of massive immigration from eastern Europe. When 200 cases of typhus appeared among Russian Jewish immigrants who had arrived in New York on French steamship in 1892, public health authorities acted swiftly. They detained the 1,200 Russian Jewish immigrants who had arrived on the ship and placed them in quarantine to keep the epidemic from spreading. The chairman of the U.S. Senate committee on Immigration subsequently proposed legislation severely restricting immigration, including the imposition of a literacy requirement. Fear that immigrants carried disease mounted with news of an approaching cholera pandemic. The epidemic, which had begun in India in 1881, did not subside until 1896, when it had spread across the Far East, Middle East, Russia, Germany, Africa, and the Americas. More than 300,000 people died of cholera in famine-stricken Russia alone. To prevent the disease from entering the United States, the port of New York in 1892 imposed a 20 day quarantine on all immigrant passengers who traveled in steerage. This measure, which did not apply to cabin-class passengers, was designed to halt foreign immigration, since few steamships could afford to pay $5,000 a day in daily port fees. Other cities including Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, and Detroit, imposed quarantines on immigrants arriving in local railroad stations. Congress in 1893 adopted the Rayner-Harris National Quarantine Act which set up procedures for the medical inspection of immigrants and permitted the president to suspend immigration on a temporary basis. A fear that impoverished immigrants will carry disease into the United States has recurred during the 20th century. In 1900, after bubonic plague appeared in San Francisco's Chinatown, public health officials in San Francisco quarantined Chinese residents. In 1924, a pneumonia outbreak resulted in the quarantining of Mexican American immigrants. After Haitian immigrants were deemed to be at high risk of AIDS during the 1980s, they were placed under close scrutiny by immigration officials. Questions to think about? 1. What factors might make a specific population particularly vulnerable to disease? 2. In your view should immigrants be viewed as a possible source of disease? Or is such a fear overdrawn? Copyright 2006 Digital History