From the Birth of Christianity to the Reformation: Religious Societies

advertisement

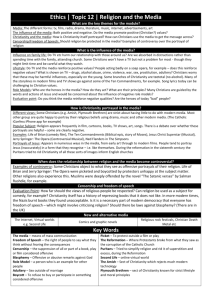

From the Birth of Christianity to the Reformation: Religious Societies and Religious Destiny, Conspiracies and Hidden Enemies Jerusalem had been under Roman occupation for quite some time. As in the other periods when the Jewish people found themselves ruled from afar, they awaited a prophet who would announce their coming freedom from foreign rule. This had happened before, and it would, it was hoped, happen again. There was even hope that the prophet would also be the final messiah, someone to usher in the final age, when the Jewish tribe of Israel would reclaim their land and establish a permanent kingdom as the chosen people of God. To Roman ears, those sorts of mutterings sounded a lot like treason, and had been dealt with before. Rebellions had come in the past, and would be crushed as they had before. Jerusalem would continue to be ruled by the local Jewish priesthood as overseen by a Roman governor, as long as they remained obedient to Caesar and the Senate. At this time, we know there were multiple branches of Jewish religion. Among them were radical groups that argued for immediate rebellion and independence, and also groups that believed that the end of the world was imminent. Around the period of Year Zero CE, many of these groups were active in the community of Jerusalem, home of the Jewish Temple and heart of the Jewish religion. Around 50 years later, letters would be written by a man who called himself Paul. They would be the first historical evidence of a group of Jewish believers who claimed that about 20 years before, a Jewish revolutionary named Jesus had taught that the world was about to change radically, and that a new Kingdom would be established. In these letters, it is clear that there is already a community of believers who thought that Jesus was a prophet foretold by other prophets, a messiah who was to usher in a new world order. The Greek word for Messiah was Christos, and so as Paul traveled through the Mediterranean world, sharing his story about Jesus, he was recruiting for the Christian religion. Based on the letters of Paul that are thought to be genuine, it would seem that this early Christianity was mainly a Jewish group, awaiting the end of the world as foretold by their prophet. Over the next several decades, this message would be extended to include non-Jews, primarily members of the Greek speaking world ruled by Rome. By 66 CE, Jerusalem had again rebelled against Roman rule, and by 70 CE, the rebellion had been crushed, the Jewish Temple had been completely destroyed, and Jerusalem itself had been decimated. Following this, the first recorded fragments of what would become the Christian Bible would emerge. While Christianity still seemed to expect the world to end and a Kingdom of Heaven to be established, it was growing fast enough that it was now being forced to deal with the Roman Empire. At this point, the Roman Authorities generally required that everyone demonstrate their obedience to the Empire and Emperor by worshiping at Roman Temples and sacrificing to the Emperor as a God. Since this violated the beliefs of the monotheistic Christians, many refused. Viewing this as treason, Christians who continued to refuse would find themselves brutally executed through gladiatorial games, crucifixion, and burning. Many of the early saints of the Church were martyred in this way. Because of this, early Christianity was an underground religion, meeting in secret and recruiting as it best could manage. The overall beliefs of this early church were fairly diverse, united by their faith in Jesus as the Christos who would usher in a new age for humanity. Over the next hundred years, Christianity would mature and start to emerge into the open, occasionally being tolerated by the ruling Emperors. By the early 300’s, one of four ruling Emperor’s had emerged who tolerated Christianity: Constantine. Although he was not the first to allow Christians to worship openly, he was the 1 first Emperor to adopt Christianity himself (although only on his deathbed,) and he took an active interest in resolving conflicts among the Christians. There was a lot to be resolved. Early in the History of the Christian Church, certain traditions had arisen. Local churches were typically headed by some sort of leader. Originally this leader was frequently an educated man or woman, who allowed worship services to occur at their house. As time passed, the inclusion of women became less frequent in the male dominated Greek world. Also, there was often some sort of respected elder who linked the various local churches, and sometimes traveled between towns to keep Christians linked into a general community. These elders evolved to become early Bishops and Patriarchs. At times, groups of these elders would meet to discuss and debate the beliefs and policies of the Church. As in any diverse group, factions formed, and different ideas circulated about what it meant to be a Christian, and what the truth of Christianity truly was. There were several branches of the Christians at this time, divided by their beliefs and their locations. A number of these concerned the basic identity of Jesus as a Man, as God, or as some combination of these. Some believed that he was a man who had the Spirit of God “adopt” him. Others argued that he was human, but his mind was divine, or that he was human but directly created as a prophet by God, or that he was an illusion created by God, and so never truly died, or that he was only Godlike, but never human, or that he really was God directly, or that…well, there were a lot more ideas out there. Other issues were the question of how (and if) Jesus was born, and how (and if) he died, and the role and relationship of the Holy Spirit (who is mentioned in some early texts as the Holy Mother) and of God the Father to Jesus. The internal struggles in early Christianity would encompass more than thirty different versions of what they thought “true” Christianity should be. The losers in these struggles were suppressed and eliminated. Their books were burned or thrown away, and are only known of because they are occasionally discussed in the letters and writings of the victors of those early holy wars, which argued for how wrong the others were. (Some of our greatest finds of these lost texts have literally been dug out of ancient garbage heaps by archaeologists.) The version of Christianity that survived and became dominant generally seemed to accept some basic ideas as essential to Christianity: Jesus was both man and God, and he truly did die and then come back to life after three days. As a god, he was the son, and along with the father part of God and the Holy Spirit, he was totally separate from the other two parts of the trinity, yet mystically they were all truly the same person. Mankind is automatically sinful, but by dying, Jesus sacrificed himself as God and man to forgive the sins of mankind, if mankind accepts him as God. After coming back, Jesus flew up to heaven in his physical form, leaving his followers to spread the word of his deeds. The various versions of Christianity that were left still disagreed about many things. How should Christians worship? Who should lead them? How could they distinguish between true Christianity and false (heretical) Christianity? One of the major dominant groups to emerge was the Roman Catholics. They argued that Jesus had appointed his apostle Simon to head the earthly Church, renaming him Peter in the process. Whoever inherited the position that Peter held in the early church would therefore be the rightful leader of the Catholic (universal) Church. Since it was believed that Peter came to rule the Christian community in Rome as the Bishop, then any bishop of Rome should be the leader of the entire Church. Over time, the holder of this position of leadership came to be known as the Pope. 2 The word pope just originally meant “Father,” as in the leader of a group of Christians. In the Eastern sections of what had been the Roman Empire; such men were known as Patriarchs, which has the same meaning. Even as the Pope gained power in the Western Church, centered on Rome, the Eastern churches remained more independent, investing some authority in local Patriarchs, but not completely centralizing their power structure. As the centuries passed, various ideas, both old and new, would come bubbling to the surface of Christian thought. Some of these would be powerful enough that they would convince a surprising number of believers, leading to a split in the Church, with each new group claiming it was the true Church with genuine authority over Christendom. Between the 4th and 11th centuries, there were at least 7 major schisms (a split caused by a difference of religious opinion) in the Christian Church. Some of these were temporary. Others were permanent, leading to new, separate churches scattered around the edges of Europe. The final one completely sundered the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Faiths. Other, smaller, disagreements about theology were sometimes labeled as heresies. Most of these directly threatened the Roman Catholic Church, because they either challenged the right of the Priesthood to interpret scripture (the bible and associated texts,) or because they claimed that the Catholic Church got some basic aspect of Christianity tragically wrong. A common issue raised in these heresies was the idea of theodicy: the attempt to explain why there is evil and suffering in the world. Classical theodicy argued that evil was a sort of test of faith, or punishment for sin. Heretical theodicy sometimes argued that a good god could not be responsible for evil…therefore there were two forces responsible for the world: a good god and an evil one. Within Christian theology, this sometimes was interpreted to mean that God was responsible for good, and the Devil for evil. The heretical element here was that this would mean that God was not all-powerful…which contradicted centuries of church teaching. Another common complaint of many heretical groups was that the established Church had drifted far from its poor beginnings. In becoming rich and powerful, it was neglecting the needs of the poor that Jesus had advocated helping first. In many cases, advocates of reform were able to begin movements within the church, starting such brotherhoods as the Franciscans. These groups remained fairly small, if popular with the poor, and frequently got in trouble with church authorities. Towards the 11th century, the Church had become a giant on the political landscape. It had the power to make or break even Kings. When King John of England refused to allow the Pope to appoint a new Archbishop of Canterbury (he claimed that he had the right to do that as King, and he wanted to appoint a friend of his,) the Pope at the time declared the King himself under interdict…this meant that King John would not be allowed to take part in any of the Church rituals like confession, communion, or even last rites. If he died while during interdict, it could be assumed he was probably headed straight to Hell. An even more potent tool of the Church was excommunication. This was when the Church basically kicked someone out. In effect, this meant that they were no longer protected by the Church, and in theory could not even talk to or do business with any Christians. For true believers, this was a fate worse than even death: not only did excommunication exile a person from their community, family and friends, but it condemned them to Hell since they could not make confession and have their sins forgiven. Not all such tools were originally aimed at problems within Christendom. One weapon the Pope wielded was originally intended for external enemies. For several hundred years, Jerusalem (considered the birthplace of the Christian religions) had been under the control of Muslim rulers. In the 11th century, Christians from all over Europe gathered and launched an attack to seize control of the Holy Lands. In order to encourage people to join this Crusade, the Pope issued a call that guaranteed salvation and a forgiveness of sins if one should die while on the Crusade. This guarantee of heaven was a powerful stimulus, as was a desire to “free” what was considered to be Jesus’s homeland. Not least, there was always the loot to be gained in the sack of a conquered city. 3 This First Crusade was a success, which would lead to the declaration of other crusades. Over time, though, Crusades became a weapon to be used not only against external enemies, but against heretical groups and uncooperative Kings in Europe itself. Within a century, a brutal war to exterminate a successful rival to the Catholic Church called the Cathars or “Good Christians” began. This was called a crusade, offering the same benefits for killing Christians, although ones that disagreed violently with the Catholic branch of Christianity. Within another century, Crusades would even be called that targeted explicitly Catholic Kings that refused to obey the Pope. Crusades had become a blunt instrument to enforce the Pope’s desires. A final element in the Church’s control was their local authority to try people in spiritual courts. In fact, the Church refused to allow Priests and other Church members to be tried in civil courts by servants of the King. Instead, they were tried in Ecclesiastical (Church) courts, regardless of the crime. In this way, Priests accused even of capital crimes like murder were tried, found guilty, and then given relatively light sentences such as a fine. This was infuriating to local rulers, because it basically removed an entire class of people from the reach of the law. More important for the Church was its ability to accuse people of religious crimes: heresy and witchcraft were the most important of these. If accused and found guilty in an Ecclesiastical Court, heretics and witches could be sentenced to death, at which point the condemned would be handed over to the civil authorities for execution. This was another point of conflict between the civil and religious authorities, because frequently what one group considered a significant crime was less important to the other. Church members could get away with major civil crimes such as theft, murder and adultery, and people considered innocent within their communities could be accused of witchcraft by the religious authorities and sentenced to death even if the local rulers and communities disagreed. A major problem at this point was that confessions could be secured through torture, and by ordeal. Torture is an enormously effective means to force people to confess to crimes of any sort. Sadly, it has been shown to have no real relationship to learning the truth in an investigation. (If the torture is painful enough, largely anyone will eventually “break” and confess to a crime or a sin, regardless of their actual innocence or guilt. In most modern settings torture is forbidden for the dual reasons that it is cruel, and it simply doesn’t work. On the other hand, in trials by ordeal, the guilt or innocence of someone would be established by forcing them to submit to some dangerous situation. If they survived with little or no harm, it was taken to mean that God wanted them to be found innocent. On the other hand, if they were badly wounded or even killed, it was a sign of their guilt, and it was assumed that they got what they deserved. The implicit belief that there was an afterlife, and that everyone would be fairly judged led to some to us almost incomprehensible decisions, such as during the Crusade against the Cathars. There was a city that contained both Catholics and Cathars that was under attack by the Catholic forces of the Crusade. When the question was raised of how to separate the good Catholics from the heretical Cathars, the commander replied “Kill them all. God will sort them out.” By the 15th and 16th centuries (the 1400’s and 1500’s) the situation had changed. There were as many angry and discontented reformers and heretics as there had always been…but now there were printing presses. In the past, someone who translated the Bible from Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic and into a common language like English would have found themselves captured, tried, and executed as a heretic in fairly short order. Now, in the time they had, their written words could be copied by printing presses and scattered across Europe. Instead of fighting a few heretical fires, soon the Catholic Church was fighting hundreds, ignited by the printed word. The Protestant Reformation had begun. Answer the following questions using a CARs format, including quoted citations. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Explain the origins of the early Christian Church Explain how the relationship between the Church and the State changed over time. Explain the major beliefs of the Catholic Church, including the relationship between God, the Church, and everyone else. Explain what procedures the Church used to for influence and control of friends and enemies. Explain some “hidden enemies” and conspiracies the Church had to deal with, and what methods they used. 6. Give your opinion for how being a religious society affected medieval Europe. 4