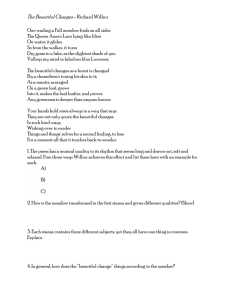

Financial Regulation in a World of Financial

Custom Fit or Off-the-Shelf

Standards: Dilemma of Financial

Reporting in Interactive World

Economy

Shyam Sunder, Yale University

III International Conference on Luca Pacioli in

Accounting History

III Balkans and Middle East Countries Conference on Accounting and Accounting History

Istanbul, Turkey,, June 19-22, 2013

An Overview

• The world is more interactive today, compared to Pacioli’s world

• Many economies of standardizing financial reporting across countries and industries; IASB and IFRS created to realize these economies

• However, also significant diseconomies of standardization; dangers of granting monopoly powers to well-intentioned experts or politicians

• The global financial crisis has already revealed some of the disadvantages; some even claim that this misguided standardization was a cause

• Written enforced standards are not, and have never been, the only way to improve financial reporting; social norms is another approach

• Doubts voiced in the U.S., China, Japan, India, and even Europe, about the wisdom of granting standards monopoly to a single body

• Time for the emerging economies to rethink their own balance between for international and local standards; written rules and social norms

• Influence others by persuasive force of ideas, not threat of punishment

• If you don’t agree, consult Pacioli.

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 2

Did Luca Pacioli Write Standards?

• Summa elucidated accounting practice of its time

• Its influence from its conformity to practice, acceptance by business, and usefulness

• No powers of prescription or enforcement

• More like Oxford English Dictionary than IFRS

• Today, powerful, well-funded bureaucracies prescribe and enforce top down written rules; no prior experience in the field is needed

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 3

Today’s World of Business and

Standards

• Great expansion of international investments and trade (beyond Pacioli’s Venetian merchants)

• This international interactivity and expansion has been used as an argument for developing:

• “… a single set of high quality, understandable, enforceable and globally accepted International

Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) through its standard-setting body, the International

Accounting Standards Board (IASB);”

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 4

IASB’s Argument for Its Monopoly

• “My confidence that we are achieving this vision is bolstered by the strong case for global standards. In a world in which capital flows freely across borders, the same economic transaction should be accounted for in the same

way, regardless of whether you are in Washington, Warsaw,

Wellington or Winnipeg. Global standards make it easier for investors to make comparisons between companies

operating in different jurisdictions. Multinational companies benefit from reduced compliance costs and

reduced translation risks when consolidating multiple international subsidiaries into a single set of consolidated financial statements.”

• Tweedie (2011)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 5

IASB’s Argument for Its Monopoly

(continued)

• “Global accounting standards will enhance the drive towards the free trade of capital internationally. By adopting a globally accepted set of standards, all companies—large and small—are able to attract

capital from a larger pool of investors, driving down the cost of capital and facilitating cross-border

mergers and acquisitions activity and strategic

investments. Finally, a common set of standards eliminates opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and permits regulatory authorities to develop more consistent approaches to supervision across the

world. In other words, financial reporting is a key element of post-crisis global regulation.”

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 6

Even without IASB and IFRS

• Most financial reporting jurisdictions allow a local monopoly in financial reporting standards for publicly-held corporations

• In the United States, statutory authority of the Securities and Exchange Commission delegateed to the Financial

Accounting Standards Board, retaining an oversight function

• In some countries, standards specified through statutes in varying levels of detail.

• A few countries—e.g., Switzerland and Canada—permit their corporations to choose among two or more sets of competing standards

• But, monopoly is the reigning norm in most jurisdictions

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 7

Let Us Rethink Standards

• What are the functions of standards?

• What improvements are achievable through standardization?

• What are undesirable consequences of standardization?

• After considering the arguments about its economies and diseconomies, what is a desirable scope of standardization?

• How much should be written down, and how much should be left to social norms?

• Should the written standards be domestic, regional or global?

• Should they be specific to industries and size of firms?

• Who should set the standards—government, private bodies or some combination of the two?

• Is it better to grant standard-setting monopolies in specified jurisdictions (as granted to the FASB in the US and to the IASB in the

European Union, and sought by the IASB across the world), or have multiple standard setters compete for clienteles who choose among alternative sets of standards?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 8

Functions of Standards

• Two basic economic reasons (Jamal and

Sunder 2007):

• Quality through standards

• Co-ordination standards

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 9

Quality Standards

• Food quality standards are a good example

• Safety of food in restaurants by standards of quality and hygiene

• Government standards are of often quality standards

Co-ordination through Standards

(Often written in private sector)

11

Financial Reporting Standards

• Roughly speaking

• Disclosure standards are quality standards

• Formatting standards are co-ordination standards

• Measurement standards are mixed; they tend to serve some aspects of both quality as well coordination functions

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 12

Advantages of Standards Well-Known

• Learning and matching costs

• Single aircraft airline

• Standardized admissions tests

• A standardized system of weights and measures

• Giving preference, if not monopoly, to some systems and designs over others is the essential feature of all schemes of standardization

(Sunder 1988 and 1997).

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 13

Costs of Standards Less Obvious

• Discourage innovation

• No competitive motivation

• Informational disadvantage of monopoly

• QWERTY keyboard

• Balancing costs and benefits of standards

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 14

Example of Getting Frozen into a Bad

Standard

15

Scope of Standards

• Domestic: traffic rules and signs for drivers

• Regional: electrical adapters

• Global: telecommunications

• Industry-specific (real estate, films) and economy-wide standards

• Size-specific and one standard for all sizes (IFRS for SMEs)

• No comparability with a “single set” of standards

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 16

IASB’s Catch Phrases

• “Single set”: Even individual countries have difficulty defending a single set of standards for all their companies in all industries; diversity of environment, legal, social and business institutions

• “Comparability”: Does application of the same revenue recognition criterion in automobile and gold mining industries yield more comparable results?

• “High quality standards”: What is quality? Pages?

• “Lower cost of capital”: And lower rate of return?

• “Promoting cross-border mergers”: Is that good or bad? For who?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 17

Do Standard Rules Yield Comparable

Results?

18

Why Written Standards?

• It is fair and efficient to write down the regulatory standards for everyone to know and comply with

(e.g., the Code of Hamurabi).

– Written standards promote our sense of fair play in a democratic society to avoid arbitrariness and partiality

– But all contingencies cannot be anticipated and written down.

– Written standards constrain discretion in enforcement

– They also serve as “road maps for evasion” and gaming to take advantage of the rules

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 19

Why Clear Standards?

• Clear standards make it easier to know what is permitted and what is not permitted.

– No standard can be made “perfectly clear”

– No matter how much detail we put in the rules, there will always be demand for further clarification and “guidance”; rule books grow

– Do additional details in standards reduce or increase the loopholes?

– 3 percent rule for Special Purpose Entities =>

Enron

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 20

A Static Ideal?

• There exists an ideal set of written reporting and regulatory standards that, once discovered and implemented, will induce corporations and banks to function efficiently in conformity with the regulations

– Dynamics of the game between managers and standard setters makes any such static ideal all but impossible

– Regulatees see standards as constraints and modify their decisions to seek their own goals

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 21

People or Structure?

• If we select knowledgeable, experienced, selfless, public-spirited, and wise individuals to constitute bodies that devise regulatory standards through deliberation and due process, we can improve the functioning of the economy.

– Yes, but individuals stand where they sit.

– We place much emphasis on the quality of individuals;

– Insufficient attention given to the structure of game that regulators and regulatees play

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 22

Crafting Standards through

Deliberation

• It is possible to construct or discover better written regulatory standards through deliberation in properly organized corporate entities (Basel

Committee, Federal Reserve, IASB, etc.).

– Assumes that such bodies can know the consequences of their actions (Cartesian perspective on the problem)

– Little evidence in history to support this proposition

– Written standards by authoritative bodies have repeatedly failed to yield their stated outcomes (e.g., global financial crisis)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 23

Specialization in Setting Standards

• Specialist standard setting bodies, standing ready to address new problems, inquiries and requests for clarifications help improve regulation

– Their existence encourages a new “clarification” game targeted at them

– They must keep a full agenda (performance)

– Revenue and budget pressures

– Over time, their written output must accumulate to a thick rule book (e.g., Basel I, II, III; IFRS)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 24

Can They Distinguish Good from Bad

Standards?

• Standard setters can tell which written standards are better, and why; and what would happen if a rule were left unwritten

– Little evidence that they know, or can know

– For example, cost-of-capital is the result of complex interactions among many factors

– These influences cannot be sorted out by ex ante analysis

– Ex post analysis of data to assess the impact of regulatory standards is confounded with other factors which may have changed simultaneously

(collinearity)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 25

Regulatory Monopolies

• Granting monopoly power in a given jurisdiction to standards written by a given body can help improve regulation; but

– Informational disadvantage of a monopoly

– No opportunity for experimentation

– No opportunity to learn from the experience of alternatives; arrogance

– No pressure to do better, or to correct errors

– Pros and cons of regulatory competition

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 26

Competition and Race to the Bottom

• A regime that encourages reporting entities to choose among the standards written by competing organizations (and paying them a royalty for the privilege) induces a

“race to the bottom” to devise less demanding standards

– Many counter examples (Stock exchanges, bond rating services, appliance standards, college accreditation, bank regulation, corporate charters across 50 states in

U.S., etc.)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 27

Force and Effectiveness

• Increase in the power of enforcement behind authoritative standards improves compliance and quality of regulation and reporting

– Increased enforcement also increases resources devoted to evasion

– Draconian punishments do not necessarily induce better behavior

– Crime, alcohol and drug abuse (recent report on failure of the War on Drugs)

– Cutting hands of thieves may not be an efficient way to reduce theft

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 28

Statutory Approach Dominates

Common Law

• The quasi-statutory approach to setting regulatory standards (writing everything down) dominates a common law approach to financial reporting (leave significant parts unwritten, and subject to professional judgment)

– Evidence?

– Constitution (U.K., U.S., Singapore)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 29

Are Written Standards Better than

Social Norms?

• Written standards backed by power of enforcement work better than unwritten social norms backed only by internal and external informal sanctions

– Social norms govern great parts of our lives including many aspects of law

– Insider trading example

– Guilty beyond reasonable doubt

– Private commercial codes (cotton, diamond trades in U.S.)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 30

Are Financial Regulation and

Reporting Improving?

• 100 years of U.S. federal bank regulation and 80 years of federal regulation of securities and financial reporting has helped improve the quality of regulation.

– Evidence?

– Is a thicker rulebook indication of better regulation?

– Perfect correlation between financial reports and stock returns?

– How do we judge if regulations are getting better?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 31

Does Permitting Fewer Alternatives

Yield Better Outcomes?

• Fewer the alternatives permitted to the regulatees, the better the quality of regulation.

– Fewer alternatives also tie the hands of the management of well-run companies who may wish to signal their confidence, competence and prospects by choosing reporting practices others find difficult to emulate.

– Permitting fewer choices reduce information through signaling

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 32

Monitor’s Bargaining Power

• Well-specified standards enhance the bargaining power of the monitor/auditor vis-

à-vis the regulated organization

– Standards also encourage regulatee to demand: show me the rule

– Reduced reliance on judgment

– More detailed the standards, greater the part of monitor’s work that can be replaced by a computer, and lower the value of the service

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 33

Individual responsibility

• Written regulatory standards strengthen the individual responsibility of managers, regulators, auditors, and investment bankers for fair representation

– On the contrary, they may undermine individual responsibility for fair representation and the big picture by shifting attention to meeting the letter, not spirit, of the specific provisions and their wording; check-box mentality

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 34

What about Education

• Written standards help improve education and attract talent to the profession

– Written standards degrade the class room from reasoning and intellectual debate to rote memorization

– They make it less attractive to young talent

35 June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards

Emphasis on Written Regulations

• Reasonable arguments for written regulations

• But also, reasonable limitations and criticisms of excessive dependence on written regulations

• Examine some consequences of increasing dependence

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 36

Basel II Bank Capital Regulation

• 2007: Capital was 11 percent of risk-weighted assets for 10 largest US banks

• But if you excluded goodwill, intangibles and deferred tax assets (which tend to become worthless under financial stress), their capital was only 2.8 percent

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 37

How Does Basel III Address this

Problem?

• More arcane and complex rules for calculating bank capital (opening more loopholes for financial engineering your way around the capital standards

• Set the capital/asset requirement to 3 percent

(about the same as the actual 2007 level)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 38

Basel I, II, III, … and Counting

• “Each new Basel (bank capital) standard attempts to correct the errors and unintended consequences of earlier versions. But instead of resulting in better outcomes, each do-over has been more complicated and less effective than the last. Most disturbingly, each fails to provide enough real capital to absorb unexpected shocks to the economy.”

Thomas M. Hoenig (Vice-Chairman FDIC), “Get Basel III Right and Avoid Basel IV,” The Financial Times, December 12, 2012.

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 39

Financial Engineering and Financial

Regulation

• These are just a few examples of the conflict between financial regulation and financial engineering.

• How long can the regulatory walls hold?

• Basel I proposed in 1988, and lasted for 16 years

• Basel II proposed in 2004 and lasted less than half-a-dozen years (until the financial crisis 2007-

10)

• Basel III proposed in 2010, and has already been hollowed under industry pressure by the end of

2012, even before its implementation began

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 40

Objectives in Financial Engineering

• “ The Financial Engineering Concentration encompasses the design, analysis, and construction of financial contracts to meet the needs of enterprises.

” (Cornell’s ORIE M.S. concentration in financial engineering)

• What are these needs?

• In at least some cases, these needs consist of finding ways of

– Reducing indebtedness on the balance sheet, or

– Reducing expense on income statement, or

– Increasing revenue on income statement, or

– Increasing deductions on tax returns

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 41

Securitization

• A form of off-balance sheet financing which involves the pooling of financial assets

• Risk transfer mechanism that allows loan originators to

optimize balance sheet management

• Allows highly rated securities to be created from less credit worthy assets

• Can be in local or foreign currency, depending on client needs

• A rapidly growing asset class with proven benefit for emerging market borrowers

• For summaries of prior deals, please visit www.ifc.org/structured finance

International Finance Corporation

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 42

Off-Balance Sheet Financing

• Borrow money in such a way so under the regulatory standards, it does not show up as a liability on the balance sheet.

• That is, find a way around written standards so an obligation to pay does not show up as a liability in the financial reports.

43 June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards

Does Financial Engineering Create

Value

• Allows highly rated securities to be created from less credit worthy assets

•Payoffs of any asset can be partitioned into parts, some of which are more risky (and yield high return) and others are less risky and yield lower return

• Can the sum of the values of these parts systematically exceed the value of the unpartitioned asset in absence of misinformation, mis-estimation, or extraneous cash consequences such as taxes?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 44

Financial & Regulatory Standards as

Constraints on Financial Optimization

• In such optimization, standards of financial regulation are treated as constraints

• Most optimization problems have hard constraints—their violation brings well-specified penalties (dual prices)

• With optimization confined by the production possibilities set and other such physical limitations, external constraints make a real difference to the final actions and outcomes

• What kind of constraints do standards offer?

• I am going to argue that these standards offer softer constraints because the forms of contracts, transactions, as well as organizational forms that businessmen can devise and use are beyond the scope of accounting standards

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 45

Redesigning Contracts

• A manufacturer needs to buy a machine for the factory

• Borrowing is an option, but the manufacturer does not want more debt on its balance sheet

• The leasing subsidiary of a bank buys the machine and gives it to the manufacturer on a long term lease— machine is in the factory but no debt on balance sheet!

• FASB writes Standard 13: leases >90%V and >75%T must be treated as capital leases (debt is back on BS)

• The bank revises the lease to levels below the thresholds specified in the standard (debt is off the BS)

• FASB goes back to work, and so on … until the leases rulebook grows to over a 1,000 pages with no end to this growth in sight

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 46

Redesigning Transactions

• Depending on the current standards of financial reporting, transactions can be redesigned to achieve the desired consequences for revenues, expenses and taxes

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 47

Redesigning the Organization

• When design of contracts and transactions is not sufficient, organizations themselves can be redesigned, or new ones created in order to have the desired consequences for balance sheets, income statements and tax returns

• Special purpose entities (SPEs and SPVs) are examples of organizations created for this purpose (see Klee and

Butler 2002 and Gorton and Souleles 2005)

• “ Hundreds of respected U.S. companies are ferreting away trillions of dollars in debt in off-balance sheet subsidiaries, partnerships, and assorted obligations ”

(Henry et al. 2002)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 48

Asymmetric Game

• Note that financial reporting standards neither have, nor can have, any say in any of these “ business ” decisions of the management

• The role of the accountant and auditor is limited to preparing financial reports given all these decisions

• While these decisions clearly consider what the accounting standards are, accountants have little freedom to take into account how and why these decisions were taken in the first place

• There is great asymmetry between the freedom available to the business decision makers and constraints on the accountant who must abide by relatively rigid written standards in deciding how to report the performance and financial status of an organization

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 49

The Net Effect

• The decision to write an accounting standard is a matter of social policy that calls for a deliberative due process; it typically takes years to determine which rules might best serve investors and others. Inevitably, these standards are written on the assumption that the current forms of contracts, transactions, and organizations will continue to be used in the future when these standards are applied

• The decision to change contracts, transactions and organization is an individual decision that may be taken within days if not hours.

Further, the scope of these decisions is virtually unbounded (except by the imagination of the businessmen). Soon after the standards are issued, the environment to which they are applied changes relative to the what the standards were written for

• The net effect: Financial reporting standards serve as relatively weak constraints (if at all) on what businesses can do and on what they report (relative to their underlying economics)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 50

Standards and Language

• Standards of financial reporting and regulation must necessarily be specified in language

• Language, in order to be useful, must necessarily have certain imprecision around the meaning of words

• Can we specify precisely the meaning of a house, or shirt, or table? Instead reliance on usage—a matter of social norms

• What happens if we try to do so?

• Regulators have tried to counter financial engineering by resorting to the fiction that more precise definitions of words, e.g., assets, liabilities, income, regulatory capital, etc. will solve the problem

• But they have not, and they cannot; bound to fail

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 51

Regulatory Language as a Constraint

• A strong provision for requiring prompt corrective action if any bank exceeds this hard size cap.

• How many financial engineers and accountants think that this is a hard cap on size, or if it is a cap at all?

• What will happen if this language became the law to cap the size of financial institutions? (independent of whether you think their size should be capped)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 52

Social Norms of Accounting and Finance

• I personally doubt that a non-cooperative game between financial engineers and regulators has led us to a socially efficient outcome

• Regulators have, over the past eight decades, increasingly come to rely on written rules as opposed to their judgment and social norms of their profession

• Financial engineers, on the other hand consider it their own professional duty to design whatever instruments/transactions/organizations will best serve the immediate interests of their clients under the prevailing written standards of financial reporting

• Social norms play a diminishing, if any, role on either side

• Is it possible that some part of the blame for the systemic failures of the recent years may be linked to this diminishing role?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 53

Ethics and Moral Code in Business

Programs

• Shiller: “ Many schools now offer a course in business ethics, and some even try to integrate business ethics into their other courses.

But nowhere is ethics seen as the centerpiece or even integral part of the curriculum. And even when business students do take an ethics course, the theoretical framework of the core courses tends to be so devoid of any moral content that the discussion of ethics must seem like some side order of overcooked vegetable ” .

• If the role of ethics in curriculum is minimal, what is the role of ethics (i.e., social consequences of our work) in choosing the substantive topics of our research

• Identifying mispricing of securities, for example, may help move prices to more efficient levels

• What about identifying a way of redesigning a transaction so a financial obligation will not show up on the balance sheet under the prevailing regulatory standards?

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 54

In Summary

• With the development of mathematical finance, financial engineers rapidly redesign transactions, instruments, and business entities to render prudential and reporting regulation in the financial services ineffective.

• This new reality has been a key element of the celebrated regulatory and reporting crises of the past dozen years.

• Band-aid solutions for this new fundamental reality (such as Basel III and IFRS fair value accounting) have little prospect of success

• What, if any thing, should we, and can we do about this?

• Are there some alternatives to bringing in a sense of social responsibility for the consequences of our research agendas? If so, let us explore them.

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 55

Good Banking is Boring

• Our lives depend on efficient functioning of many systems (e.g., electrical wiring, plumbing, foundations of our buildings, telephones, and computer networks)

• All such essential and critical systems are made efficient and routine to the point of being boring, low paying jobs, following pre-specified procedures and codes.

• Innovations are slow, but made only after much experience and regulatory deliberation.

• Excitement in such essential fields portends disaster

(e.g., electrical wiring of Boeing 787 Dreamliner)

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 56

Creativity in Finance

• These consequences of financial engineering suggest that the social consequences of creativity in finance can be as socially detrimental as creativity in accounting

• Objects of finance consist of (are defined) entirely by the relevant covenants and the accounting system

• To the extent financial institutions have significant social externalities, and receive special support in form access to borrowing from the central banks

• Their transactions have to confined to those conforming to a pre-approved template.

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 57

A Path for Emerging Economies

• Recall “the Washington Consensus” for 1990s

• Similar orchestration of effort to sell IFRS monopoly in the world

– Once granted, almost impossible to change

– No competition, experimentation, comparisons, field testing, customization, or learning

• Instead, allow IFRS as an option from 2 or 3 permitted alternatives, including domestic standards

• Let companies choose, as Canada and Switzerland do

• Standards competition supervised by legal authority

• Over time, each country will evolve a partially customized system of financial reporting to serve it best

• Yes, some additional cost, but improvement and robustness to financial engineering

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 58

Beware of the Pied Piper

• In the German legend the Pied

Piper enchanted the children of a village with his music, and they followed him to their doom, never to return.

59

Thank You.

Shyam.sunder@yale.edu

www.som.yale.edu\faculty\sunder

References

• Hans J. Blommestein, “ The Financial Crisis as a symbol of failure of academic finance (a methodological digression), The Journal of Financial Transformation, Fall 2009.

• G. Gorton and N. Souleles, “ Special Purpose Vehicles and Securitization, ” FRB Philadelphia Working

Paper, 2005.

• Henry, David, Heather Timmons, Steve Rosenbush, and Michael Arndt (2002), “ Who else is hiding debt?, ” Business Week (January 28), 36-37.

• J. Huber, M. Shubik, and S. Sunder, “ Default penalty as disciplinary and selection mechanism in presence of multiple equilibria, ” Cowles Foundation Working Paper 1730, October 2009.

• K. Klee and B. Butler, “ Asset-Backed Securitization, Special Purpose Vehicles

• and Other Securitization Issues, ” Uniform Commercial Code Law Journal 35 (2002), 23-67.

• J. Mason, E. Higgins and A. Mordel, “ Asset Sales, Recourse, and Investor Reactions to Initial

Securitizations: Evidence Why Off-balance Sheet Accounting Treatment Does not Remove Onbalance Sheet Financial Risk ” LSU Working Paper, 2009.

• Robert J. Shiller, “ How Wall Street learns to look the other way, ” The New York Times, Feb. 8, 2005.

• Shyam Sunder. Theory of Accounting and Control. Southwestern Publishing, 1997.

• Shyam Sunder, “ Determinants of Economic Interaction: Behavior or Structure.

” Journal of Economic

Interaction and Coordination 1, no. 1 (May 2006): 21-32.

• Shyam Sunder, “’ True and Fair ’ as the Moral Compass of Financial Reporting, ” in Cynthia Jeffrey, ed., Research in Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting (Forthcoming 2009).

June 19, 2013 Sunder: Financial Regulation Standards 61