Slide 1

advertisement

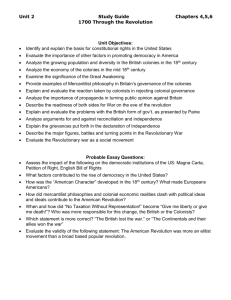

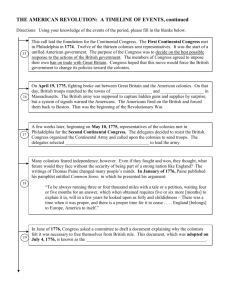

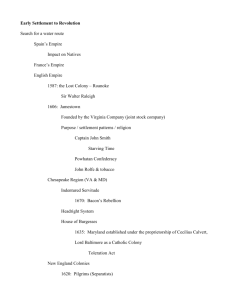

The Intolerable Acts began a tumbling snowball that within two years led to American independence. In September 1774, delegates from each of the Colonies, except Georgia, met in the First Continental Congress. Among the delegates were John and Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, George Washington, John Dickinson, Edmund Rutledge of South Carolina, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and John Jay of New York. Congress debated but rejected a plan that would have created the Continental Association, similar to Franklin’s Plan of Union. It approved an embargo on all British goods. And it accepted an idea from Thomas Jefferson’s Summary View of the Rights of British America that only the King, not Parliament, had power to govern the colonies. Known as the Dominion Theory, it intended to circumvent Parliament and plead its case directly to the crown. It was a potentially dangerous argument, because if the king backed Parliament, then the colonies would have little room for further maneuvering. The Congress adjourned in October with orders to meet again in May 1775. Along with the Coercive Acts, Britain sent a military governor General Thomas Gage to Massachusetts. In October 1774, Massachusetts defied Gage and met in assembly. It named John Hancock head of the Committee on Safety. The Committee was empowered to call up a colonial militia. Hancock organized special units of the militia in to squads known as Minutemen. From this point onward, Massachusetts truly is in rebellion. Battle of Lexington and Concord Old North Bridge Lexington Green The Road Back Battle of Lexington and Concord: First battles of the War of Independence: Major General Thomas Gage, British Military Governor, sent troops to capture two rebel leaders: John Hancock and Sam Adams. On April 19th, the redcoats met the Minutemen on Lexington Green, someone fired a shot and war began. British troops routed the militia, but suffered over 250 casualties on their return to Boston. 93 colonials died in the battles. With shots finally fired, New England prepared for war, but the other colonies were less united in their response. In New York, Patriots organized the militia, while loyalists asked Gage to suspend further attacks until orders came from England. New Jersey was split between patriots and Tories, led by Governor William Franklin (illegitimate son of Ben Franklin). Quaker Pennsylvania divided between pacifists and fighters, while the rest of the colony divided into Patriots, led by Franklin, and Loyalists, led by Dickinson. In the Chesapeake, Maryland opposed revolution, while Virginia (and especially Patrick Henry) supported it. A month before Lexington, Henry urged the House of Burgesses to organize a militia, giving his oft-quoted speech, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Loyalism was stronger in the Lower South, particularly in the back-country among the Scots-Irish who distrusted the Low Country planters. But a strong patriot contingent also existed in the Carolinas, as well as Georgia. On May 20th, Mecklenburg County issued the “Resolves” and declared its independence: “We do hereby declare ourselves a free and independent people; are, and of right ought to be a sovereign and self-governing association, under the control of no power, other than that of our God and . . . Congress: To the maintenance of which Independence we solemnly pledge to each other our mutual co-operation, our Lives, our Fortunes, and our most Sacred Honor.” “There is something charming to me in the conduct of Washington: a gentleman of one of the first fortunes upon the continent, leaving his delicious retirement, his family and friends, sacrificing his ease and hazarding all in the cause of his country.” John Adams Second Continental Congress: Beginning in May 1775, after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, it was the first to include delegates from all of the colonies. Most wanted to avoid further conflict, but understood preparedness was important. In June, the Congress named George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775): First major battle of the war. The British won the battle north of Boston, but it was a pyrrhic victory; they suffered 1,054 casualties. After Bunker Hill, John Dickenson tried once again to restore peace. He wrote the “Olive Branch Petition,” sent to England on July 8th, 1775. We beg leave further to assure your Majesty that notwithstanding the sufferings of your loyal colonists during the course of the present controversy, our breasts retain too tender a regard for the kingdom from which we derive our origin to request such a reconciliation as might in any manner be inconsistent with her dignity or her welfare. . . . The apprehensions that now oppress our hearts with unspeakable grief, being once removed, your Majesty will find your faithful subjects on this continent ready and willing at all times, as they ever have been with their lives and fortunes to assert and maintain the rights and interests of your Majesty and of our Mother Country. We therefore beseech your Majesty, that your royal authority and influence may be graciously interposed to procure us releif [sic] from our afflicting fears and jealousies occasioned by the system before mentioned, and to settle peace through every part of your dominions, with all humility submitting to your Majesty's wise consideration; . . . and that in the meantime measures be taken for preventing the further destruction of the lives of your Majesty's subjects; and that such statutes as more immediately distress any of your Majestys colonies be repealed: For by such arrangements as your Majesty's wisdom can form for collecting the united sense of your American people, we are convinced, your Majesty would receive such satisfactory proofs of the disposition of the colonists towards their sovereign and the parent state, that the wished for opportunity would soon be restored to them, of evincing the sincerity of their professions by every testimony of devotion becoming the most dutiful subjects and the most affectionate colonists. Thomas Jefferson wrote a companion piece that explained the action of forming colonial militias: On the Necessity of Taking Up Arms, July 1775. “Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great, and, if necessary, foreign assistance is undoubtedly attainable. . . . With hearts fortified with these animating reflections, we most solemnly, before God and the world, declare, that, exerting the utmost energy of those powers, which our beneficent Creator hath graciously bestowed upon us, the arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume, we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverence, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die freemen rather than to live slaves.” Lest this declaration should disquiet the minds of our friends and fellow-subjects in any part of the empire, we assure them that we mean not to dissolve that union which has so long and so happily subsisted between us, and which we sincerely wish to see restored. -- Necessity has not yet driven us into that desperate measure, or induced us to excite any other nation to war against them. -- We have not raised armies with ambitious designs of separating from Great-Britain, and establishing independent states. [I]n defence of the freedom that is our birthright . . . against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms. We shall lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, and not before. Ironically, the Olive Branch Petition reduced the colonies’ ability to negotiate because if the king rejected it, then there would be little for the colonies to do but either give in or become independent. News of Bunker Hill arrived in England just before the petition. Many in Britain also wanted conciliation, but the vote to accept the petition lost 86 to 33. In August, King George III called the colonials rebels and rejected the petition. Instead, he turned to Europe for troops. Several German states complied, most notably that of Hesse, which supplied 13,000 Hessian mercenaries. John Adams: Boston lawyer, led Independence Movement at Second Continental Congress. Although short in stature, he had a strong mind, a huge ego, and a way of driving his colleagues crazy with sheer force of character. He was ambassador to Britain during the Confederation era, 1st Vice-POTUS and 2nd POTUS. Thomas Jefferson: Main author of the Declaration of Independence, inventor, writer, and musician. He was ambassador to France during the Confederation era, the 1st Secretary of State, 2nd Vice-POTUS, and 3rd POTUS. “I HAVE never met with a man, either in England or America, who hath not confessed his opinion, that a separation between the countries would take place one time or other: And there is no instance in which we have shown less judgment, than in endeavoring to describe, what we call, the ripeness or fitness of the continent for independence.” Tom Paine Common Sense (1776): Pamphlet written by radical English Quaker Tom Paine and published in Philadelphia in January 1776. It argued that it made no sense for the colonies to stay part of England. Its fiery language and clear reasoning helped convince the large segment of undecided to join the independence movement To CONCLUDE, . . . many strong and striking reasons may be given to show that nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independence. Some of which are, It is the custom of Nations, when any two are at war, for some other powers, not engaged in the quarrel, to step in as mediators, and bring about the preliminaries of a peace; But while America calls herself the subject of Great Britain, no power, however well disposed she may be, can offer her mediation. Wherefore, in our present state we may quarrel on for ever. While we profess ourselves the subjects of Britain, we must, in the eyes of foreign nations, be considered as Rebels. [Last]ly. — Were a manifesto to be published, and despatched to foreign Courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceful methods which we have ineffectually used for redress; declaring at the same time that not being able longer to live happily or safely under the cruel disposition of the British Court, . . . at the same time, assuring all such Courts of our peaceable disposition towards them, and of our desire of entering into trade with them; such a memorial would produce more good effects to this Continent than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain. Under our present denomination of British subjects, we can neither be received nor heard abroad; the custom of all Courts is against us, and will be so, until by an independence we take rank with other nations. These proceedings may at first seem strange and difficult, but like all other steps which we have already passed over, will in a little time become familiar and agreeable; and until an independence is declared, the Continent will feel itself like a man who continues putting off some unpleasant business from day to day, yet knows it must be done, hates to set about it, wishes it over, and is continually haunted with the thoughts of its necessity. Declaration of Independence: Founding document of the U.S. signed on July 4, 1776. It was written by committee (Ben Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston) with most of the work done by Jefferson: the document is in four parts: 1. a preamble, offering an introduction as to the purpose of the document 2. explanation of natural rights, based on Locke's “social contract:” life, liberty, pursuit of happiness 3. presentation of the list of complaints against King George III 4. statement of intent, i.e. says that the colonies are sovereign and independent Battle of Yorktown (August – October 1781): Just miles from the site of Jamestown, the U.S., under the command of George Washington and with considerable help from the French, defeated the British after a long siege and Cornwallis surrendered, ending the war. Treaty of Paris (September 1783): Treaty ending the War of Independence: with it the U.S. gained control of all the land east of the Mississippi River, north of Florida, and south of British Canada; U.S. gained fishing rights in the Grand Banks. In November, the British evacuated New York City. A month later, General Washington resigned his commission as Commander of Continental Army, showing that a civilian government would run the U.S.