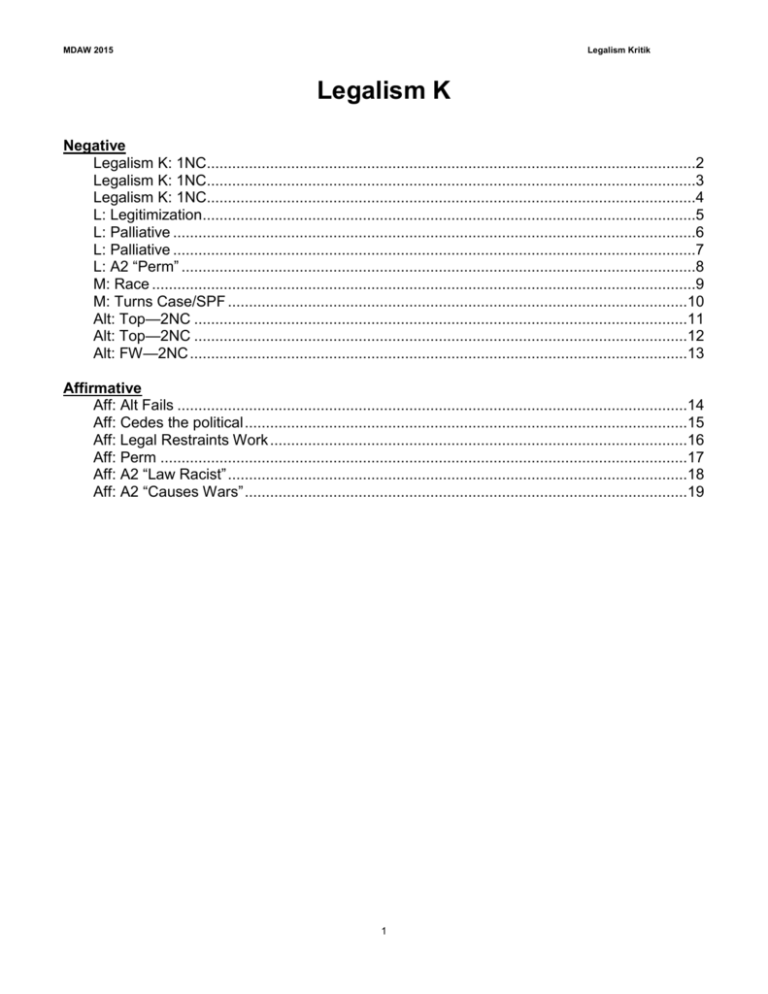

MDAW15_Legalism K (Practice, 19)

advertisement