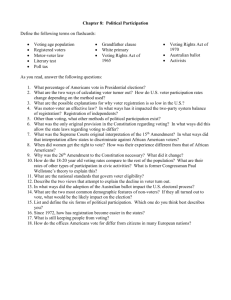

Law of Democracy – Lupu – Fall 2011

advertisement