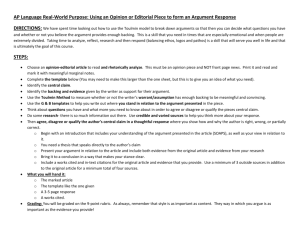

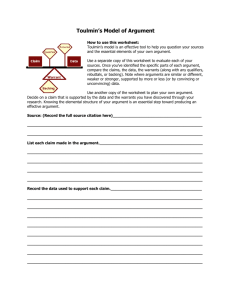

Toulmin Explanation

advertisement

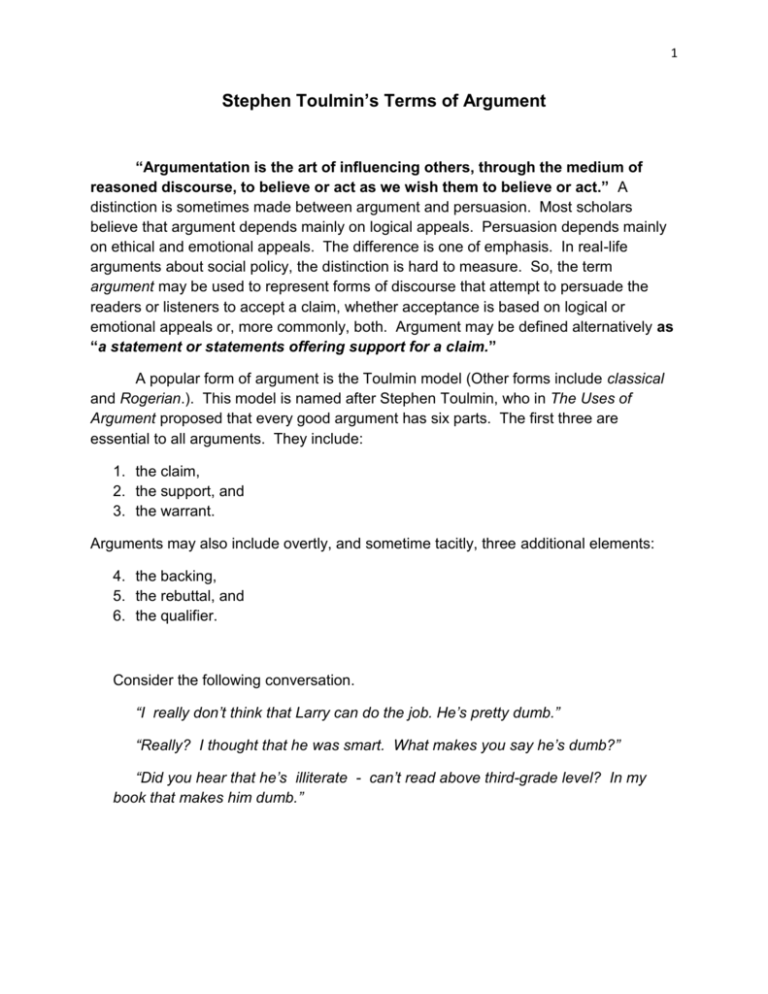

1 Stephen Toulmin’s Terms of Argument “Argumentation is the art of influencing others, through the medium of reasoned discourse, to believe or act as we wish them to believe or act.” A distinction is sometimes made between argument and persuasion. Most scholars believe that argument depends mainly on logical appeals. Persuasion depends mainly on ethical and emotional appeals. The difference is one of emphasis. In real-life arguments about social policy, the distinction is hard to measure. So, the term argument may be used to represent forms of discourse that attempt to persuade the readers or listeners to accept a claim, whether acceptance is based on logical or emotional appeals or, more commonly, both. Argument may be defined alternatively as “a statement or statements offering support for a claim.” A popular form of argument is the Toulmin model (Other forms include classical and Rogerian.). This model is named after Stephen Toulmin, who in The Uses of Argument proposed that every good argument has six parts. The first three are essential to all arguments. They include: 1. the claim, 2. the support, and 3. the warrant. Arguments may also include overtly, and sometime tacitly, three additional elements: 4. the backing, 5. the rebuttal, and 6. the qualifier. Consider the following conversation. “I really don’t think that Larry can do the job. He’s pretty dumb.” “Really? I thought that he was smart. What makes you say he’s dumb?” “Did you hear that he’s illiterate - can’t read above third-grade level? In my book that makes him dumb.” 2 Put into outline form, the warrant or assumption in the argument becomes clear. CLAIM: Larry is pretty dumb. EVIDENCE: He can’t read above third-grade level. WARRANT: Anybody who can’t read above third-grade level must be dumb. The argument represented in diagram form shows the warrant as a bridge between the claim and the support (evidence). Support Claim Warrant (Expressed or unexpressed) The argument above can be written like this: Support Larry can’t read above third-grade level. Claim He’s pretty dumb. Warrant Anybody who can’t read above thirdgrade level must be pretty dumb. 3 The full argument structure may be diagrammed as follows: Qualifier (Q) Data (D) Claim (C) Restriction (R) Warrant (W) Backing (B) Let’s look at a somewhat less frivolous example, adapted from Toulmin (1964 111). Qualifier (Q) Data (D) almost certainly Claim (C) Peterson is not Roman Catholic. Peterson is a Swede. Restriction (R) Warrant (W) unless he has converted A Swede can be taken to be almost certainly not a Roman Catholic. Backing (B) The proportion of Roman Catholic Swedes is less than 2%. The argument may be written thusly: If Peterson is a Swede, so Peterson is not Roman Catholic, since a Swede can be taken to be almost certainly not a Roman Catholic, because the proportion of Roman Catholic Swedes is less than 2%. 4 The Claim The claim is the main point of an argument, and answers the question, “What are you trying to prove?” or “What do I want to prove?” Synonyms for “claim” are thesis, proposition, conclusion, main point. Like the thesis, it may be explicit or implicit (stated or implied). The claim organizes the entire argument and everything else in the argument is related to it. The best way to check your claim during revision is by completing the statement: “I have my audience to think that … .” Kinds of claims 1. Claims of fact assert that a condition has existed, exists, or will exist, and are based on data or facts that the audience will accept as being objectively verifiable (empirical evidence). e.g., The present cocaine epidemic is not unique. From 1885 to the 1920s cocaine was as widely used as it is today. Horse racing is a dangerous sport. California will experience colder, stormier weather for the next ten years. 2. Claims of value attempt to prove that some things are more or less desirable than others. They express approval or disapproval of standards of taste and morality. They include advertisements, reviews. They argue about what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly. e.g., You have a tasteful writing style. “Bob Cooper hangs his heart on his sleeve as he attempts to mend his broken family -and put some fun in dysfunction -before he dies. Cooper's authenticity is palpable and it anchors the piece from beginning to end” (Robin Waples, Review of Last Christmas). Football is one of the most dehumanizing experiences a person can face (Dave Meggyesy, Linebacker for the St. Louis Cardinals). 5 3. Claims of policy assert that specific policies should be instituted as solutions to problems. The expressions should, must, or ought to usually appear in the statement. e.g., Prisons should be abolished because they are crime-manufacturing concerns. Our first step must be to immediately establish and advertise drastic policies to bring our population under control (Paul Ehrlich, biologist). Major employers must consciously employ more women in major positions of responsibility, and pay them according to their position rather than their sex. Support Support supplies the evidence, opinions, reasons, examples, and factual information about the claim that make it possible for the reader to accept it, used by the arguer to convince an audience that his or her claims are sound. Synonyms include proof, evidence, reasons, and data. To plan support, ask, “What information do I need to supply to convince my audience of my main point (claim)?” Common types of support include: 1. facts and statistics, testimony from experts, 2. opinions (authoritative and personal), Caution, personal opinion should be convincing, original, impressive, interesting, and backed by factual knowledge, experience, good reasoning and judgement. 3. examples in the form of anecdotes, scenarios, and cases, 4. emotional appeal made to the values and attitudes of the audience. To help you focus on and recognize the support, complete this sentence: “I want my audience to believe that … [the claim] because … [list the support].” Warrant Warrants are assumptions, general principles, conventions from specific disciplines, widely held values, commonly accepted beliefs, and appeals to human motives. Warrants originate with the arguer, but exist in the minds of the audience. They can be shared or in conflict. 6 Warrants may be implicit (hidden, implied) or explicit (overtly stated), but either way they are part of the argument. They are often taken for granted. They allow the reader to make a connection between the support (or data) and the claim. Example 1: Claim - Abortion should be illegal. Data - “Thou shalt not kill.” Warrants - a.) abortion is a sin, b.) life begins at conception, c.) human potential is lost. Example 2: Claim - Adoption of a vegetarian diet leads to a healthier and longer life. Support - The authors of Becoming a Vegetarian Family say so. Warrant - The authors are reliable sources of information on diet. (Note that the author of the claim may need to provide proof of the authors’ credentials in science and medicine, in case the reader thinks they are quacks.) In this case, if the reader does not accept the warrant, he or she cannot accept the claim. Example 3: Claim - Laws making marijuana should be repealed. Support - People should have the right to use any substance they wish. (Note that we could have included medical evidence that show that marijuana is harmless. In this case the warrant would be different.) Warrant - No laws should prevent any citizens the right from exercising their rights. (Note also that definitions may also be used as warrants. But again, if the definition is not accepted then the claim resulting from it cannot be accepted either.) Backing Backing is additional evidence provided to support or “back up” a warrant whenever there is a strong possibility that your audience will reject it. When writing your argument, determine if backing is needed by identifying the warrant and then determining whether or not you accept it. Rebuttal A rebuttal established what is wrong, invalid, or unacceptable about an argument and may also present counter-arguments, or new arguments that represent an entirely different perspective or point of view on the issue. 7 Ask yourself, “What are the other possible views on this subject?” and “How can I answer them?” When analysing claims, look for phrases like “some may disagree,” others may think,” or other opinions that are commonly held are” followed by the opposing idea. Qualifier An argument cannot be expected to demonstrate a certainty. Usually it only establishes probability. Therefore, avoid presenting information as an absolute or a certainly. Qualify what you say with phrases such as “very likely,” “probably,” “it seems,” Summary D DATA (if): The observations, facts, raw material from which we draw a claim. Includes examples, evidence, quotes from literature (in literary analysis). C CLAIM (therefore, so, then): The opinion that results from the data, our understanding of the meaning of the data. Q QUALIFIER (on the whole, usually): Indicates or signals that the claim is not absolute. R RESTRICTION (except when): Indicates conditions that would render the claim totally invalid. W WARRANT (since, because): The reason(s) why our claim is valid, including definitions, experience, similarities to other systems, argument patterns. B BACKING (on account of): Beliefs which authorize the warrant at the outset, basic understandings of larger principles. References Rotenberg Toulmin, S. The Uses of Argument. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1964. Woods, Nancy, Perspectives on Argument. [ToulminExplanation.docx]