American Imperialism

advertisement

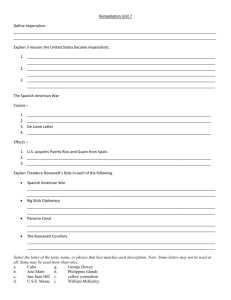

American Imperialism before WWI American Imperialism • While many European states were busy creating empires in Africa and Asia, many Americans began to feel the pangs of expansionism too. • According to Professor Frederick Jackson Turner (University of Wisconsin), the frontier was officially “settled” by 1890. American Imperialism • By the 1890’s, the United States was the world leader in industrial output and agricultural production. • American business wanted to expand into new markets. • Arguments in favor of expansion had great appeal. American Imperialism • Expansionists also argued that Americans had a right and a duty to bring Western culture to the “uncivilized” peoples of the world. • Many expansionists, especially those in the military (like Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan), proposed that America needed overseas territories to protect our merchant fleet. American Foreign Policy • American foreign policy for the first 100+ years of the republic was dictated by George Washington’s Farewell Address. • Washington begged his countrymen to avoid “foreign entanglements.” American Foreign Policy • Except for the Monroe Doctrine, the United States primarily stayed isolated throughout most of the 19th century. • American attitudes began to change after the Civil War. American Imperialism: Hawai’I • The Nation of Hawaii: • By 1875 American sugar • • planters had brokered a treaty between Hawai’I and the U.S. An 1882 amendment to the treaty gave the U.S. Pearl Harbor as a naval and refueling base. The growing power of the Americans ousted King Kalakana (the Bayonet Constitution). American Imperialism: Hawai’I • In 1891, Queen Lili’uokalani came to the throne. She resented the growing power of the Americans. • In 1893 the sugar planters rebelled against the Queen’s attempt to limit their power. American Imperialism: Hawai’i • The American Ambassador called for the Marines, who deposed the Queen in the Hawaiian “Revolution” of 1893. • A new “Americanized” constitution was installed. • President Grover Cleveland refused to annex Hawai’I because he said he was “ashamed of the whole affair.” American Imperialism: Hawai’I •After Cleveland left office, his successor, William McKinley, pushed Congress to annex Hawaii (which was done in 1898). •Hawaii became a U.S. territory in 1900. • It became a state in 1959. American Imperialism: The Venezuelan Border Dispute and the Monroe Doctrine • After Hawaii, the next test for American foreign policy came in Venezuela (1895). Here, the United States and Great Britain almost went to war over the Monroe Doctrine. • Britain and Venezuela were arguing over the border between British Guiana and Venezuela (no one cared until gold was discovered). American Imperialism: the Venezuelan Border Dispute American Imperialism: the Venezuelan Border Dispute • When Britain refused to negotiate through American arbitration, President Cleveland asked Congress for the authority to defend Venezuela. • Britain backed down and agreed to arbitration, which favored their claims anyway. • This was the last time the U.S. and Britain were at odds with each other. American Imperialism: Cuba • The next major test would come in Cuba. In the late 1890’s, Americans opened their daily newspapers to find shocking and lurid tales of violence and revolution in Cuba, a Spanish owned island 90 miles south of Florida. American Imperialism: Cuba • In 1898, the United States put aside its long standing policy of neutrality to intervene in the Cuban revolution. • Actually, American interests in Cuba went back many decades… Cuba • In 1823, John Quincy • Adams was the Secretary of State under President Monroe. He compared Cuba to a ripe apple. A storm he said, might tear that apple “from its native tree” and drop it into American hands. The Cuban rebels of the 1890’s were giving Spain the storm JQA had hoped for 75 years earlier. Cuba • The Ostend Manifesto (1854) was an attempt by President Franklin Pierce to extend the southern boundary of the U.S. by annexing Cuba. The U.S. was willing to negotiate with Spain a payment of $120m. Cuba • If Spain refused to sell, Pierce was prepared to take Cuba by force and make it a slave state. • This was leaked to a New York newspaper, and faced with a firestorm of criticism, Pierce repudiated the Manifesto and disavowed any knowledge of it. Cuba, and the Coming of War • Spain held on tightly to her “Pearl of the Antilles.” This was the last remnant of Spanish colonialism in the New World and Spain did not want to give it up. • For the United States, Cuba’s close proximity, climate, and soil made her a great place for investment. Americans had invested over $50 million in Cuba (more than anywhere else) and had trade with the island in excess of $100 million/year (nearly 25% of all American exports). Cuba, and the Coming of War • The U.S. wanted naval bases in Cuba. • Growing American sympathy for the rebels fighting for their freedom created a tense situation with Spain. • By 1898, many Americans were eager for a conflict with Spain over Cuba. Cuba, and the Coming of War • Sympathy for the Cuban rebels, reports of Spanish atrocities against the Cubans (the first “concentration” camps), and anger towards a European power still trying to maintain control of colonies in the Western Hemisphere stirred Americans to action. • The “yellow” press whipped the nation into a frenzy with lurid accounts, usually exaggerated, of conditions in Cuba. Cuba, and the Coming of War • Newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst sent a photographer to cover Cuba with the famous words: “You provide the pictures, I’ll provide the war!” Cuba, and the Coming of War • A typical headline read: “Blood on the roadsides, blood in the fields, blood on the doorsteps, blood, blood, blood!” • Such sensational reports were often inaccurate, but they succeeded in stirring American anger against Spain. Cuba, and the Coming of War • President McKinley hoped to resolve the Cuban issue without military intervention, but several events prevented that from happening. Key things besides “yellow” journalism were the De Lome letter and the Battleship Maine. Cuba, and the Coming of War • De Lome was the Spanish ambassador to Washington. In a private letter written to a friend in Spain in early January 1898 (that was intercepted and reprinted by the press), De Lome called McKinley “weak and catering to rabble…a low politician…” • De Lome was then recalled to Spain. Steps Leading to War • President McKinley sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana Harbor to protect American citizens and American investment (and pressure Spain). Steps Leading to War • On Feb. 15, 1898 the • Maine exploded in Havana Harbor, killing 266 American sailors (of the 350 on board). American newspapers immediately blamed Spanish saboteurs. The Spanish denied having anything to do with the disaster. Steps Leading to War • Hearst and Pulitzer newspapers ran headlines that said “Remember the Maine…to Hell with Spain!” The nation was now poised for war. The Coming of War • Spain knew it could not defeat the United States, and on April 9, 1898 agreed to all the concessions over Cuba the United States asked for. • President McKinley tried to resist the political pressure to declare war, but fearing his party (Republican) would lose face and power, he acquiesced. • Two days later (April 11, 1898), McKinley asked Congress to declare war on Spain. The Spanish-American War • Before hostilities really began, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, secretly ordered the American Pacific fleet (known as the Asiatic Squadron) out of port in Hong Kong to sail to the Philippines right away. • American naval ships hadn’t been to the Philippines in 22 years. The Spanish-American War • Roosevelt ordered the Spanish fleet captured or destroyed. • At dawn on May 1, just days after war was “officially” declared, Commodore Dewey and a small fleet of six American ships surprised the enemy. From the bridge of his flagship, the cruiser Olympia, Dewey commanded the attack on the surprised Spanish fleet. • “Remember the Maine and down with Spain!” was the battle cry of his gunners. The Spanish-American War • In a four-hour engagement, without losing a ship or a man (except for an engineer who died of heat exhaustion), Dewey’s fleet destroyed the Spanish Pacific fleet of 10 ships in Manila Bay. The Spanish-American War • The American ships fired off nearly 6,000 shells, Spanish casualties numbered nearly 400, and the Americans captured the crucial naval station at Cavite. • The Americans had such an easy time of it that at one point in the engagement, Dewey ordered his men to cease firing so they could have breakfast. They returned to the attack after breakfast. • “I control Manila Bay completely,” he cabled Washington, “and can take the city The Spanish-American War • Dewey’s battle order to his captain on the Olympia “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley,” immediately became as famous as David Farragut’s “Damn the torpedoes!” • Newspapers in the U.S. called Dewey’s victory “The Greatest Naval Engagement of Modern Times,” and compared it to Horatio Nelson’s defeat of the French at Trafalgar. The Spanish-American War • Because of his immediate fame and popularity, Dewey went from Commodore to rear admiral to Admiral of the Navy, a rank and honor revived by Congress and abolished after his death. The president was his only superior. • Given the pathetic condition of the outgunned and mostly unarmored Spanish fleet, however, Dewey’s victory was more like a turkey shoot. The Spanish-American War • The Spanish admiral, Patricio Montojo, had fully expected defeat so he moved his ships to a shallow anchorage. • This way his men could cling to the rigging when their ships went down instead of drowning. The Spanish-American War • American troops easily captured Manila and took complete possession of the Philippines in August (1898). The Spanish-American War • When war finally came, few were more eager to fight than the young Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Teddy Roosevelt. • Roosevelt resigned his position, and formed a volunteer regiment (the First Volunteer Calvary Regiment). The Spanish-American War • Sent to Cuba to fight for Cuban independence, Roosevelt’s unit (nicknamed the “Rough Riders”) saw action in Santiago (Cuba’s 2nd largest city). • Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill became the stuff of legend. His unit was joined by the African American units of the 9th and 10th Cavalries. The Spanish-American War • Two days later, the combined American forces destroyed the Spanish fleet in Santiago, causing the Spanish army in Cuba to surrender. The Spanish-American War • The war lasted just four months. America lost over 5000 soldiers, but only 400 to actual combat. The rest died of diseases (heat exhaustion, yellow fever, malaria, typhoid, food poisoning, etc). • Secretary of State John Hay famously called this action “a splendid little war.” • This marked the end of the Spanish Empire in the New World. The Spanish-American War • The United States had turned from her position of isolationism to become an international power. • The United States now joined the ranks of the world’s colonial powers. The Treaty of Paris (1898) • Having just defeated Spain, the following terms were agreed to in October 1898: • Cuba would gain independence from Spain, but Spain would retain Cuba’s heavy debts. • Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded to the United States. The Treaty of Paris (1898) • The United States agreed to pay Spain $20.0 million for the Philippines. The U.S. now had a launching point for trade in the Far East. • The United States now had the overseas empire many had dreamed of (with all the positives and negatives that went with it). American Imperialism The Philippines • As a result of the Spanish-American War, the United States could no longer be truly isolated again. As we will see in WWI and leading up to WWII, the U.S. tried to revert back to a position of isolation, but it was never achieved. The world had gotten too small. The Philippines • President McKinley saw in the Philippines the chance to “educate and uplift and civilize and Christianize…” the Filipinos. Meanwhile, they had been Catholic for three centuries. • The Philippines had helped the United States against Spain, much the same way Cuba helped the United States. Filipinos expected independence (like that granted Cuba) to be their reward. The Philippines • Filipinos were outraged when Congress did not approve independence for the Philippines. Most Filipinos felt betrayed by the United States, and that they had merely traded one master (Spain) for another. • Filipino nationalists, under the direction of Emilio Aguinaldo, rose up in armed rebellion against American rule in 1899. Aguinaldo had helped the Americans in ridding the Philippines of Spanish rule. The “Philippine Insurrection” • From 1899-1902, American • military forces clashed with Filipino nationalists. Aguinaldo and 70,000 rebels spent more than two years fighting for their nation’s freedom in a bloody, and often brutal war. After Aguinaldo was captured, the war ended. 4,300 Americans and 57,000 Filipinos were killed in this little known American war. America and the World • After the Philippine insurrection was put down, movements were made to give the Filipinos more autonomy. However whenever these came before Congress, they were voted down because it was felt the Filipinos needed more time to “develop” a true democracy. • Today, Puerto Rico and Guam are still territorial possessions of the United States. The Philippines was finally granted independence after WWII, in 1946. Foreign Policy under Teddy • Teddy’s “Big Stick” • diplomacy: Based on the West African proverb “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” Essentially the Roosevelt Corollary grew out of this attitude. Foreign Policy under Teddy • It has come to mean any diplomatic negotiations that are backed up by the threat of (American) force. This is sometimes called “Gunboat Diplomacy.” Foreign Policy under Teddy • The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine: In the early 1900’s Venezuela and the Dominican Republic defaulted on loans from Britain, Germany, and Italy. European warships menaced Latin American/ Caribbean nations. • Teddy Roosevelt invoked the Monroe Doctrine and sent American battleships to force the Europeans out. The Europeans were furious, saying if they could not use force to get their debts paid, the U.S. must take responsibility. Foreign Policy under Teddy • To satisfy this demand, Roosevelt announced the Roosevelt Corollary in 1904. He declared the U.S. would exercise “international police power” to get Latin American/Caribbean nations to honor their financial commitments. • Through the 1920’s, this policy sent American troops to Nicaragua and Honduras (and other places) to guarantee repayment of foreign debts. Teddy and the “Big Ditch” • As the U.S. expanded its • interests in the Pacific, it wanted to be able to move its naval fleet easily between oceans without making the long voyage around South America (8000 nautical miles). Teddy Roosevelt proposed building a canal across the narrow Isthmus of Panama, which was a province of Columbia. Teddy and the “Big Ditch” • Columbia did not want to • give the U.S. the rights to build fearing it would lose control of the region. When it looked like another canal might be built in Nicaragua, key Panamanian business and civic leaders seized the moment and started a rebellion. Panama and the “Big Ditch” • So in November 1903, with U.S. encouragement, • Panama rebelled against Columbia. When Columbia sent troops to put down the rebellion, 10 American warships prevented the Columbian troops from landing. The rebel leaders, among them my uncle’s grandfather, quickly declared Panamanian independence (creating the Republic of Panama) and signed a document granting the U.S. rights to build the canal. Panama and the “Big Ditch” • The U.S. was also granted rights to the Canal Zone, averaging 10 miles wide and just over 50 miles long. • This would be considered sovereign American territory until given back to Panama in 1999. Panama and the “Big Ditch” Panama and the “Big Ditch” • Building the canal began in 1904. Pittsburgh's furnaces roared as more than fifty mills, foundries, and machine shops churned out the rivets, bolts, nut, girders, and other steel pieces the canal builders needed. • The Canal was a modern marvel of American engineering, technological, and medical advancement. When it opened in 1914, the Canal was a symbol of U.S. power and influence in Latin America. Teddy and the “Big Ditch” • TR became the first • sitting president to leave the country while in office. Here he sits in a 95 ton Bucyrus hydraulic bucket lifter. Teddy Roosevelt considered the Canal his legacy and his greatest achievement.