Developing an Evaluation System for SWPBS

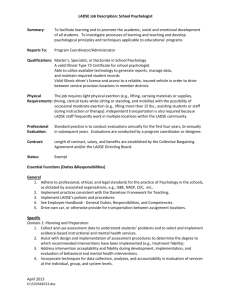

advertisement

TEACHING ACADEMICS AND BEHAVIOR: WHAT COMES FIRST? [SOLVING THE-CHICKEN-OR-THE-EGG DILEMMA] BOB ALGOZZINE, AMY MCCART, AND STEVE GOODMAN National PBIS Leadership Forum Hyatt Regency O’Hare Rosemont, Illinois October 27, 2011 Objectives Provide a brief overview of research addressing the relationship between academic achievement and social behavior and effective practices for teaching academics and behavior. Share models and evidence of comprehensive systems for improving academic and social behavior outcomes for all students. Provide an opportunity for question-answer collaboration. Relationship between Academics and Behavior What We Know Research Level “Nonhandicapped students with greater depressive characteristics were more likely to be hyperactive and less likely to be accepted by their peers. They were also less likely to achieve adequately in reading recognition, reading comprehension, arithmetic, and writing” (Cullinan, Schloss, & Epstein, 1987, p. 96). “…the poorer the academic performance, the higher the delinquency” (Manguin & Loeber, 1996, p. 246). “Early learning problems and aggressive behavior have problematic consequences extending far into the life course, and they have been found to be correlated early in children’s schooling” (Kellam, Mayer, Rebok, & Hawkins, 1998, p. 486). “It is well recognized that children with disabilities exhibit learning and behavioral problems at an early age” (Kamps et al., 2003 p. 212). “The concomitant relationship between academic underachievement and emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) is one that has been repeatedly established in research literature” (Wehby, Falk, Barton-Arwood, Lane, & Cooley, 2003, p. 225). “A critical step in prevention and reduction of behavior problems is helping students with behavior disorders develop academic competence. Unless academic deficits are remediated and these students are successful in their efforts, they will continue to become frustrated, will develop a negative perception of school, and will most likely act out” (Bowen, Jenson, & Clark, 2004; p. 132). “…U.S. and international literacy campaigns routinely invoke the positive effects of literacy and schooling upon child development, public health, and crime prevention” (Vanderstaay, 2006, p. 331). Correlation is not causation. [C A and B] Relationship between Academics and Behavior What We Know: Correlation is not causation…[C A and B] Research Level Causal relationship has not been documented, but the quest continues to capture and motivate the searchers. … an “archive” sample” of 7639 students in 14 high schools in Australia…(p. 149). …although confidence yields the most positive educational outcomes, courage can be considered an educationally effective response in the face or presence of fear (p. 145). Martin, A. J. (2011). Courage in the classroom: Exploring a new framework predicting academic performance and engagement. School Psychology Review, 26, 145-160. Relationship between Academics and Behavior What We Know: Correlation is not causation…[C A and B] Research Level …and the beat goes on… This study improved upon prior studies by using structural equation modeling to investigate the hypothesized mediating effect of social competence and to account for measurement error. The sample included 1,042 participating students from 23 middle schools. Wang, M-T. (2009). School climate support for behavioral and psychological adjustment: Testing the mediating effect of social competence. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 240-251. Relationship between Academics and Behavior What We Know: Correlation is not causation…[C A and B] Research Level .42 Reading (Age 5) Reading (Age 7) …and the beat goes on… -.21 -.23 -.27 -.24 Behavior (Age 5) Behavior (Age 7) .69 Trzesniewski, K. H., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., & Maughan, B. (2006). Revisiting the association between reading achievement and antisocial behavior: New evidence of an environmental explanation from a twin study. Child Development, 77, 72-88. .70 Reading (Year 2) Algozzine, B., Wang, C., & Violette, A. S. (2010). Reexamining the relationship between academic achievement and social behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13, 3-16. Reading (Year 3) -.03 -.12 -.25 -.10 Behavior (Year 2) Behavior (Year 3) .72 Relationship between Academics and Behavior: What We Know System Level: An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure Focus on Conditions of Teaching…Not Conditions of Students. Prevent Decrease worsening and development of reduce intensity new problem of existing behaviors problem behaviors Eliminate triggers and maintainers of problem behaviors Teach, monitor, and acknowledge appropriate behavior Relationship between Academics and Behavior: What We Know School Level: Identical Twins from Different Mothers Academic Systems Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Intensive Correction 1-5% 5-10% Secondary Interventions Some Students (At-Risk) Targeted Remediation Universal Interventions All Students School-Wide Prevention Behavior Systems 80-90% Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Intensive Correction 1-5% 5-10% Secondary Interventions Some Students (At-Risk) Targeted Remediation 80-90% Universal Interventions All Students School-Wide Prevention Relationship between Academics and Behavior: What We Know School Level: Behavior and Reading Improvement Center Research Academic Instruction Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Intensive Correction 10-20% 20-30% Secondary Interventions Some Students (At-Risk) Targeted Remediation Universal Interventions All Students School-Wide Prevention Behavior Instruction 50-60% Tertiary Interventions Individual Students Intensive Correction 1-5% 5-10% Secondary Interventions Some Students (At-Risk) Targeted Remediation 80-90% Universal Interventions All Students School-Wide Prevention Relationship between Academics and Behavior: What We Know: Behavior and Reading Improvement Center Research Focus Academic Level I II III Description District-adopted core reading program implemented by classroom teachers with intensive and subsequent ongoing professional development from product consultants. 90 minutes of teacher-directed instructional time per day 30 minutes of independent work time per day Peer Coaching Fluency Building (PCFB) Project-developed intervention implemented in selected classrooms to support the literacy development of students with diverse learning needs. Students participated in PCFB during the 30 minutes of teacherdirected instructional time assigned to independent work. The intervention took roughly 10-12 minutes to complete once students learned the routine. Classroom teachers used this additional fluency practice at least three times a week. Practice Court Reading (PCR) Project-developed targeted reading intervention with intensive and ongoing professional development. Students participated during instructional time assigned to independent work. Project-supported classroom assistants or volunteer interventionists provided 30-minute intervention sessions at least three times a week. Reading Mastery Classic District-adopted intensive reading program with intensive and ongoing professional development. Students participated during instructional time assigned to independent work. Project-supported classroom provided 30- to 45-minute intervention sessions at least three times a week. Fidelity We documented acceptable levels of primary reading instruction (e.g., 90% taught of teachers taught Phonemic Awareness and 82% taught Letter Recognition phase of the lessons; 82% included Independent Work Time during literacy block). The average treatment fidelity documented across unannounced observations was 1.20 and was considered acceptable as evidence that the intervention was implemented as intended. Fidelity ranged from a low of 35% to 100%: when translated into Convergent Evidence Scale scores, the range of scores was from 1-5 with a mean of 4.55. The average percentage of completed items across fidelity checklists was calculated by the interventionists and ranged from 80.1% to 100%. Relationship between Academics and Behavior: What We Know: Behavior and Reading Improvement Center Research Focus Behavior Level I II III Description Behavior Instruction in the Total School (BITS) Project-developed school-wide behavior support program implemented by classroom teachers with intensive and subsequent ongoing professional development focused on: Shared school-wide beliefs about teaching behavior. School-wide expectations for appropriate behavior. Commitment to school-wide systems rather than people or programs as the basis for sustainable outcomes. School-wide approach for teaching behavior. School-wide approach for continuous monitoring and evaluating of behavior instruction. Implemented continuously throughout school day. Social Skills Intervention Project-directed targeted behavior interventions including student contingency contracting, teacher or student self-monitoring systems, small group social skill instruction, and teacher or student selfevaluation systems for students identified in need of extra support but not intensive support. Classroom teachers implemented interventions continuously throughout school day with assistance from school-based project staff. Small group intervention was provided 2-3 times a week (30 min/session) by school psychologists and other support staff. Functional Behavior Assessment Project-directed intensive behavior including functional behavior assessments, individualized positive behavior support plans, and wrap-around services. These evidence-based practices were implemented by teams of professionals within each school guided by individualized behavior improvement plans; interventionists and details varied with needs of students receiving tertiary instruction. Fidelity We documented school-wide positive behavior support expectations as well as teachers’ use of (a) reinforcement, (b) monitoring of student behavior, (c) appropriate voice tone, and (d) expected correction procedure with 30-minute observations in all classrooms in treatment and control schools at least twice a year. Evidence of these critical features in Control schools was consistently below that for Treatment schools. The average percentage of completed items across fidelity checklists was calculated by the interventionists monthly and ranged from 80% to 100%. The average percentage of completed items across fidelity checklists was calculated by the interventionists and ranged from 80% to 100%. Teaching Academics and Behavior: What We Need To Know Classroom Level: Questions Drive Instruction Essential Questions to Ask Teaching Academics Teaching Behavior What skills do I want my kindergarten class to know and do… What skills do I want my kindergarten class to know and do… What do I want my 9th grade English I students to know and do … What do I want my 9th grade English I students to know and do … What skills do my students need to be successful? What skills do my students need to be successful? Teaching Academics and Behavior: What We Do School and Classroom Level: Assessment Drives Instruction Team-Initiated Problem Solving Teaching Academics and Behavior: What We Do School and Classroom Level: Good Teaching is Good Teaching What Does Effective Teaching Look Like? Academic Instruction Behavior Instruction Systematic and Simple Demonstrate Demonstrate Practice Prove Teaching Academics and Behavior: What We Do School and Classroom Level: Good Teaching is Good Teaching What Does Effective Teaching Look Like? Identify Learning Gap Develop Hypothesis Implement and Evaluate Solution Reteach or Move On… What Who, Where, When, and WHY Deliver Intervention Assess Fidelity …the beat goes on… TITANIC Will it float? Build it? Did it float? …the legend continues… We need a bigger boat… Teaching Academics and Behavior: Evidence from Practice Kentucky The School Research Partnership is a consortium of researchers studying academic and behavioral components of effective instruction and management in school settings. Academic and Behavioral Response to Intervention (ABRI) is structured to provide state-wide access to support with the emphasis on creating an infrastructure toward sustainability and capacity building within schools and educational cooperatives. The project has created a series of training video vignettes demonstrating each of 10 Primary Level instructional strategies in a variety of K-12 classroom contexts in order to provide guidance to educators and administrators. Florida The Florida Response to Intervention (RtI) website provides a central, comprehensive location for Florida-specific information and resources that promote schoolwide practices to ensure highest possible student achievement in both academic and behavioral pursuits. Teaching Academics and Behavior: Evidence from Practice Oklahoma Oklahoma State Department of Education has been implementing tiered interventions for academics and behavior over the last several years. Amy McCart, Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas worked with teams in Oklahoma to formalize their approach and implement specific strategies for teachers and administrators to integrate their behavioral and academic approaches. Michigan Michigan’s Integrated Behavior and Learning Support Initiative (MiBLSi) works with schools to develop a multi-tiered system of support for both reading and behavior; PBIS is a key part of the Initiative’s process for creating and sustaining safe and effective schools. Steve Goodman is Director of Michigan Integrated Behavior and Learning Support Initiative and PBIS Coordinator. Presentation Questions and Answers References Algozzine, B., Wang, C., & Violette, A. S. (2010). Reexamining the relationship between academic achievement and social behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13, 3-16. Bowen, J., Jenson, W.R., & Clark, E. (2004). School-based interventions for students with behavior problems. New York: Kluwer Academic. Cullinan, D., Schloss, P. J., & Epstein, M. H. (1987). Relative prevalence and correlates of depressive characteristics among seriously emotionally disturbed and nonhandicapped students. Behavioral Disorders, 12, 90-98. Kamps, D.M., Wills, H. P., Greenwood, C. R., Thorne, S., Lazo, J. F., Crockett, J. L., Akers, J. M., & Swaggart, B. L. (2003). Curriculum influences on growth in early reading fluency for students with academic and behavioral risks: A descriptive study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 11, 211-224. Kellam, S. G., Mayer, L. S., Rebok, G. W., & Hawkins, W. E. (1998). Effects of improving achievement on aggressive behavior and of improving aggressive behavior on achievement through two preventive interventions: An investigation of casual paths. In B. P. Dohrenwend (Ed.), Adversity, stress, and psychopathology (pp. 486-505). New York: Oxford University Press. Manguin, E., & Loeber, R. (1996). Academic performance and delinquency. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research: Vol. 20 (p. 145-264). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Martin, A. J. (2011). Courage in the classroom: Exploring a new framework predicting academic performance and engagement. School Psychology Review, 26, 145-160. Trzesniewski, K. H., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., & Maughan, B. (2006). Revisiting the association between reading achievement and antisocial behavior: New evidence of an environmental explanation from a twin study. Child Development, 77, 72-88. Vanderstaay, S. L. (2006). Learning from longitudinal research in criminology and the health sciences. Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 328350. Wang, M-T. (2009). School climate support for behavioral and psychological adjustment: Testing the mediating effect of social competence. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 240-251. Wehby, J. H., Falk, K.B., Barton-Arwood, S., Lane, K. L., & Cooley, C. (2003). The impact of comprehensive reading instruction on the academic and social behavior of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 11, 225-238.