MLA.Form.Seventh.Edition

advertisement

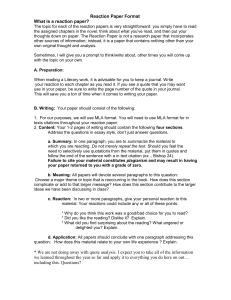

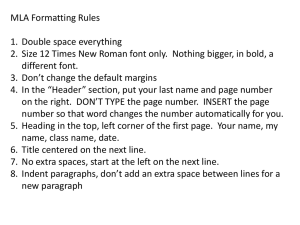

Tuya 1 Alyssa N. Tuya Professor Keith Jones College Composition 9 September 2010 What a Wonderful Paper: The MLA Form on a Beautiful Morning Notice, first of all, that this paper has no cover page. The first page of the paper serves as the cover page, containing all the information necessary. An added benefit is that no extra trees have to be chopped down and processed for that superfluous sheet of paper. Also note that the date is not in the usual order and is not broken up by a comma. Whether this is to confuse matters or to make chronological sorting easier, I’m not quite sure, though I assume the latter. Additionally, notice that everything—without exception—is double-spaced in the MLA form. The header, the paragraphs of the essay, block quotes, the title, the works cited page— everything—is simply double spaced. Set your computer to double space, never hit the carriage return more than once in a row, and don’t look back. Each line should be exactly the same distance from every other line in the entire document. Each paragraph begins exactly one-half inch from the left margin. And, speaking of margins, each one is exactly one inch in from the edge of the paper. Please notice that the righthand margin, in the MLA form, is not justified. The only exception to the one-inch-from-theedge rule is the header, which is placed exactly one-half inch from the top edge and one inch from the right edge. It appears on every page, without exception. Even the works cited page—if the paper cites works—has this header. The header is made up of the last name of the student, a space, and the page number. Students often experience frustration in attempting to get the page numbers to work properly. Often, this results from an attempt to turn on the word processor’s Tuya 2 automatic page numbering while having a separate running header containing the student’s last name. Do not turn on automatic page numbering. Instead, you should open the header, set it to right-justify, type your last name and a space, and then look for a way to insert a page number in the header. Normally, you will click on a number sign of some sort. Additionally, the title is somewhat interesting, considering the subject matter. At least it doesn’t say “MLA Handout” or, worse yet, just have a blank space where the title should be. And it doesn’t say “To Use the MLA Form or Not To Use the MLA Form: That is the Question.” Be certain always to have a title and to put some effort into it. Please, for the sake of your professor’s sanity, don’t title your papers things like “Assignment.” This is often indicative of a certain lack of resourcefulness on the part of the student. Please note that the title is not in all capital letters, not underlined, and not in a different font. The words in the title should give it all the zing it needs (though you may put a title in boldface, if you feel led so to do). Although punctuation is the caramel that holds together the peanuts of this nut roll called the English language, it is often misunderstood. Now that you have this document, this will be the case no longer. We start with the apostrophe. When it appears in a pronoun, the apostrophe always indicates a contraction. I’m fine. We’re all fine. You’re fine, too. He’s all right; she’s writing well; it’s going quickly; they’re going to be up all night. I’ve had worse. I’ll see about that. We’ll do more later. We’ve been working too hard. You’ll see my point eventually. She’s reading a book. She’s had three overdue books today. There’s no cause for alarm. Where’s the fire? When’s the truck getting here? Who’s got a cell phone? Who’s the man with the coat? How’s the weather? What’s the problem? Any of these could be expanded without damaging Tuya 3 the meaning of the sentences. I am fine. We are all fine. She has had three overdue books today. What is the problem? To put it quite bluntly, apostrophes in pronouns are always contractions. They never indicate the possessive. If you remember this, you will be able to keep the following problematic words straight: it’s (contraction of “it is”) vs. its (the possessive of “it”); they’re (contraction of “they are”) vs. their (the possessive of “they”) vs. there (location indicator or introductory word, as in “there is” or “there are”); you’re (contraction of “you are”) vs. your (possessive of “you”); and, finally, who’s (contraction of “who is”) vs. whose (the possessive of “who”). The apostrophe, in other cases, is used to indicate the possessive case, and it is usually followed by the letter S. Where is the cat’s bowl? Who took the book’s cover? The secret agent’s cover was blown by the silly spy’s nonsense. The curse’s effect was to prevent the team from winning. The lady’s purse is small. When the noun you wish to put in the possessive case is plural and ends with an S, add the apostrophe without an additional S. What are all the cats’ names? Who took these books’ covers? The seven curses’ effects were to do a lot. The ladies’ purses are all small. The Joneses’ cars are always green. Consider how many possessives there are! What are the possessives’ qualities? What is the wall’s color? What are the walls’ colors? My parents went to the parents’ banquet, but one parent’s car wouldn’t start. Do you know the Joneses? They’re very nice. We should go to the Joneses’ house for dinner. When the noun you wish to put in the possessive case is plural but does not end in S, add an apostrophe and the letter S. The child’s garden is big, but the children’s garden is bigger. That man’s salary is small; that woman’s salary is larger; but women’s salaries are, Tuya 4 unfortunately, not always larger than men’s salaries are. The red sock’s odor was pungent. But the Red Sox’s pitching was good. When the noun you wish to put in the possessive case is singular and ends with an S, add the apostrophe and an additional S. The boss’s son drove all the bosses’ cars. The moss’s color is green. The coin toss’s result was tails. When a proper noun you wish to put in the possessive case is singular and ends with an S, add the apostrophe but no additional S. Jesus’ birthday is celebrated on December 25. The commandments were held in Moses’ hands. Professor Jones’ explanation of the rules of grammar make sense. Avoid using apostrophes when making nouns plural. This is not usually troublesome in the case of simple nouns: one dog, two dogs; one chicken, two chickens. When nouns are numbers or abbreviations, things get a bit trickier. You should say that the 1980s were rough and that you bought two CDs that you grew to hate, though you found them at one of your favorite URLs. You had to go to three different ATMs to get the money to pay for them. Luckily, you had gotten As and Bs on your report card, so your parents weren’t upset. Apostrophes are used in contractions and in the possessive forms of nouns—though, remember, not of pronouns. Thus, you might say that 1942’s Jack Benny differed from 1953’s, though his radio program with roughly the same cast was broadcast throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The possessive is formed in the same way whether you’re talking about 1953’s Jack Benny or Jack Benny’s violin or the violin’s case. When pronouns enter the picture, the rule changes: you would no more talk about he’s violin than you would about it’s case—it should be his violin and its case. Why? Apostrophes in pronouns are always contractions. They never indicate the possessive. Tuya 5 Capitalize the first word of a title or a subtitle and every other major word in it. The Freedom of Life: Of Oxen, of Sheep, and of Cattle. Capitalize the first word of a sentence. That’s fine. Capitalize the first word of a quote if the first word is the first word in a sentence. She said, “We ought to go to the store.” She said that we should “go to the store.” Capitalize proper nouns. Go to Egypt, France, and Italy, Mr. Jones, and see Mel, Anne, and Greg in Cairo, Paris, and Florence. Nicknames are proper nouns. I said to Dad, “Shall I go?” But I asked my mother, “Where is our dog, Soup?” Go to the professor. When will Professor Jones be in? The colon’s job is to introduce something: a list, a long quotation, or a phrase to which you wish to draw attention. Please note that: to draw attention. Shakespeare was fond of quoting names: “Bernie, Ernie, Helen, Sue, Michael, Rowan, Algeroo.” The colon is at its stylistic best when it appears after the grammatical sense of the sentence is complete: when what appears before it is an independent clause. A colon is preceded by an independent clause, but it does not have to precede one. Briefly, because I don’t want to muddle the issue, a colon may also separate a title from a subtitle (see the title of this very document), and the independent clause rule does not apply in that case. The semicolon’s main job is to separate two independent clauses. If the clause that precedes the semicolon is independent, but the clause that follows it is not, the semicolon is being used incorrectly. It’s easy to use well; it’s easy to overuse. The only other job of the semicolon is to make a list clear when the use of commas alone would not be able to do so. Everyone should fall into line, march out the door, and follow the yellow line. Everyone should fall into line; march out the door; and, once we all get the signal, follow the yellow line. Please go to Houston, Texas; Ashmore, Vermont; and St. Paul. Tuya 6 Afterwards, you may wish to visit East St. Louis, Illinois; St. Louis; and Hermann. I read Shakespeare, who loves words; Chaucer, who loves plots; and Milton, who loves neither. Before we move on to talk about the comma, that sly dog of the punctuation world, it would help to understand what manner of things are possible with two independent clauses. You may do one of three things with them. One: Leave them alone. Let them exist as two separate sentences. I like short sentences. You don’t care for them. Two: Connect them with a semicolon. I like short sentences; you don’t care for them. Three: Connect them with a comma and a coordinating conjunction. I like short sentences, but you don’t care for them. Although the math seems specious, these three good things to do with two independent clauses are subject to four common errors. Error One: to fuse them . . . to make them into a runon (or fused) sentence. I like short sentences you don’t care for them. Error Two: to connect them with a semicolon and a conjunction. I like short sentences; and you don’t care for them. [Note: Although this is, technically, an error, you might have a valid stylistic reason for doing so. Understand that you are breaking a rule—and which rule you’re breaking—if you choose to do so.] Error Three (and possibly the most common): to connect them with only a coordinating conjunction. I like short sentences but you don’t care for them. Error Four: to connect them with only a comma—the comma splice. I like short sentences, you don’t care for them. With this in mind, let’s examine the comma in more detail. Please, please read section 3.2.2 of The MLA Handbook and pages 40-48 of The Guide to Rapid Revision very carefully. There are rules for comma use, and those rules help our understanding immensely. They are important for man, woman, and child. Regrettably, many students fail to provide a comma after an introductory phrase or after the penultimate item in a list. Tuya 7 In addition to its use in helping a conjunction to separate two independent clauses, a comma performs other functions. It separates items in a list. There are many examples above, below, and to the right of this sentence. It sets off an introductory phrase—no matter how short it may be!—from the rest of the sentence. Last night, I stayed up late writing this. After I managed to finish, I headed for bed. It sets off non-restrictive phrases. Chattanooga, the queen of Tennessee cities, has over 300,000 residents. Stealing a policeman’s helmet, a crime of which Wooster stands accused, is too common. The lake, which freezes over every January, is warm enough for swimming. Let’s have no more confusion on the differences between dashes and hyphens. Generally, the hyphen is used to connect compound adjectives. I enjoy Vietnamese-American literature. My four-year-old daughter does, too. I found a three-letter word. I study sixteenthcentury literature. But when such hyphenated phrases become objects, whether direct or of prepositions, they often lose their hyphens. Have I told you that my daughter is a four year old? I gave a book to the two year old. The word had three letters. Shakespeare is one of the best writers of the sixteenth century. Dashes are not hyphens. A dash is longer—it is composed of two hyphens. It is used to set off non-restrictive phrases to which you wish to give particular emphasis. Dashes are—and I wish to emphasize this—not hyphens. Note that a dash is either made up of two hyphens and no spaces--like so--or of a long dash—if your computer is able to make one. One hyphen-this is what a hyphen masquerading as a dash looks like, and pretty silly it looks, too-will not serve as a dash. The latest edition of the MLA doesn’t demand italics, but it encourages its use. In this, it differs from previous editions. For this course, you may use underlining or italics Tuya 8 interchangeably—provided the italic script is distinctive enough and provided that you maintain consistency. Avoid the overuse of underlining to emphasize. Usually, your sentence structure can be framed to give a point all the emphasis it needs; in those rare instances where underlining helps, use it—but note such instances are rare. I have used them a few times in this delineation of all things compositional, but never without cause. Also, don’t feel the need to put a word or phrase in all capital letters to emphasize it; so, too, will one exclamation point serve—you don’t need to use three or four. Your language should carry most of the emphasis necessary: word choice can be an exquisite means to accomplish the stunning, shattering emphasis you require. Underlining is also used for the titles of major works. I read a review of Upbeats and Beatdowns in The New York Times. Apparently, Five Iron Frenzy read Hamlet, saw Les Misérables, and went to Star Trek: Generations. Use quotation marks around the titles of minor works of various kinds. I still haven’t heard “Combat Chuck,” but I’ve read “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” I’ve lost my copy of my essay “Is there an Ophelia in this Text?” but I have a copy of “What a Wonderful Paper: The MLA on a Beautiful Morning.” There are a few more troublesome words in the English language, including to, two, and too. The first indicates an infinitive or is a preposition; the second is a number; the third means either “also” or “to a greater extent than is desirable.” “I want to go, too.” “Sorry, but you’re too late.” “Passed” and “past” are commonly mistaken for each other. I have passed out handouts on this subject in the past. Confusion also strikes the unwary upon encountering “than” and “then.” I knew him far better then; in fact, I knew him better than most people did. I’ve also often noticed a tendency to use the phrase “often times” when the word “often” will do. Beginning a sentence with the word often is often awkward. This can often be corrected by moving the word to a different, but appropriate, place in the sentence. Sometimes students will Tuya 9 say “I do this to better the situation.” A better way to say this is “I do this to improve the situation.” I also encounter a fair number of unnecessary, unscholarly interjections. Especially in scholarly essays, avoid beginning a sentence with “well” or “so.” The conjunctive adverb “however” is also frequently misused. People often separate it from the rest of the sentence with a comma; however, because it is what it is, it should be proceeded by a semi-colon and followed by a comma. If you use it, however, in the first of two independent clauses or in a sentence with one independent clause, a semi-colon would be inappropriate. Finally, “alright” and “alot” do not exist, though “already” does. For the first two, simply make the appropriate substitution. All right is all right to say. This shouldn’t give you a lot of trouble. Along similar lines, note that the word “already” is different from the phrase “all ready.” The adjective “everyday” differs from the phrase “every day” as well. Allow me a few moments to talk about the peculiarities of quotations. Ellipsis are addressed in section 3.7.5 of The MLA Handbook (Gibaldi 114-18). When omitting parts of a quote, the periods which make up an ellipsis should have spaces between them, and between the words on either side: “It is . . . important” (Hoop 375). Beware of this, because some word processing programs attempt to fix this for you, eliminating the spaces. In Microsoft Word, you can avoid this by turning off that option—as well as the very annoying option of converting typed URLs into hypertext—by doing the following. For the former, go to Insert and pull down to Autotext. Click on the Autocorrect tab, scroll down to the one in question (“Replace . . . with …”) and delete it. For the latter, go to Insert and pull down to Autotext. Click on the Autoformat tab, then remove the check from “Replace . . . Internet and Network Paths with Hyperlinks.” That will prevent your computer from turning URLs blue and underlining them—you will then, therefore, be able to present them in proper MLA form. Tuya 10 If you were to quote one “word,” or even “an entire phrase,” remember that punctuation remains inside the “quotes.” This is always the case in American Standard Punctuation. Singing “Lah dee dah,” the youth sat on the table. She said, “I’ve been here since Tuesday,” but she had been here since Monday night. But we will “look out at the winds.” When she asked, “Have you seen the show?” he answered, “No!” The only exceptions to this rule are the colon and the semicolon. They manage to slip out of the quotation marks, particularly in titles. I once wrote a paper called “‘Two Chairs for Friendship’: A Kierkegaardian Approach to Exercise.” I said, “The colon and the semicolon have a particular power”: escaping. Hamlet says three things: “When the wind blows north-northwest, I know a hawk from a handsaw”; “Now I am alone”; and “That’s all, folks!” If you are quoting someone who is quoting someone, use single quotation marks inside double quotations marks. One of my professors always said, “Jack Benny always used to say, ‘This is Jack Benny talking.’” If you are quoting a sentence that ends with an exclamation mark or a question mark, that ending punctuation proves more powerful than the comma that would usually occur there and cancels it out: “This is Jack Benny talking!” said Jack Benny on numerous occasions—rather than “This is Jack Benny talking,” Jack Benny mumbled. For some reason, the inappropriate use of single quotation marks has increased in recent years. It seems that some students think that if you only quote one “word” you need to use “single” quotation marks. Such a belief is simply erroneous. Allow me to utter a final word on using quotation marks: if you happen to need to use a phrase that is considered cliché—something you should try to avoid anyway—don’t call attention to it by “putting it in quotes.” Even if you are an “old dog” attempting to learn “new tricks,” you can and should “avoid” this. Tuya 11 Occasionally, you may need to make an editorial interjection in a quotation. If you do so, please use square brackets to indicate material that you have inserted into the text. Jones writes that “the use of language by [Milton] is studiously significant” (220). Hoop argues that “the character of Hamlettte [sic] is multifarious” (22). In the first example, the bracketed editorial interjection probably replaces a pronoun; in the second, the author wishes to make it evident that Hoop is the one who has grievously misspelled Hamlet’s name—“sic” is Latin for “thus.” I’d like to turn from grammatical concerns back to more general writing advice at this point. Though quotes are often quite useful—and, indeed, necessary in some instances—one place where it is inappropriate to quote is in the first sentence of your paper. When the first student tried this (in 379 B.C.), it worked rather well. Since that time, however, it has become cliché and trite. It is now, in all instances, boring. Avoid it like the plague. This rule holds for the use of dictionary definitions as well, especially, though not by any means exclusively, at the beginning of an essay. Unless a word is very obscure, or you are using The Oxford English Dictionary to demonstrate a significant change in the word’s meaning over time, quoting from a dictionary reminds all professors of high school essays, which is something you never want them to think about when they are reading your college essays. Along similar lines, since the dawn of time, students have started their essays with phrases like “since the dawn of time.” This is anathema. Always avoid such huge, sweeping statements, even if they do not begin your essay. They are never acceptable. Please note the very amusing intentional hypocrisy in the previous two sentences. Should you avoid rhetorical questions? Are long strings of rhetorical questions even worse than asking one? Is there a better way to introduce a topic? The answer to these three questions is, in order, usually, definitely, and most certainly. You might get by with one Tuya 12 rhetorical question in an essay, but please don’t overdo it. I would prefer you avoid them altogether. Is the passive voice always to be avoided? For my purposes, no. When the passive voice becomes awkward, you should rephrase the sentence structure. But if it’s clear or necessary, I have no objections to it. Many students have informed me that they have been told never to use the first person or a contraction in an essay. Both of these can be overdone, but I do not ask you to avoid them on principle. Avoid them when they become awkward, repetitive, or weak. Observe how the following sentence can be made stronger when the first person is eliminated: “I see the current strife in Northern Ireland as rising out of a strong background of animosity and stubbornness, and I see this history as being in direction opposition to the current reforms and solutions.” “The current strife in Northern Ireland rises out of a strong background of animosity and stubbornness, and this history is in direct opposition to the current reforms and solutions.” Most phrases like “I intend in this paper to establish that” or “I believe that” can be cut without detriment. One should also know when one should avoid the “one should” construction: when it becomes awkward and / or pretentious (i.e., usually). Gender-specific—that is, gender-exclusive—language ought to be avoided. Careful reconstruction of a sentence is usually all that is required: putting such sentences in the plural is often a quick (and usually adequate) solution. See me if you find such rephrasing difficult—I can help. If you use a thesaurus, please also use a dictionary. The word you may be using to replace another word may not actually be appropriate. This is particularly the case when introducing quotations and desiring variety. For my purposes, the verbs used to introduce quotations do not need to be all that varied: stick to “says,” “states,” “argues,” and, perhaps, Tuya 13 “posits”—but only when the verb does what you wish it to do. It is doubtful that the person you are quoting actually articulates, verbalizes, pronounces, or asseverates a direct quotation. Perhaps it would be wise to point out two other things that you should be careful about. Whenever you wish to use a number less than one hundred, please write out the entire number. Some say that you should write out numbers with three syllables or less, but that’s not the best rule. You might have to mention the number thirty-seven right next to the number thirty-six, and that might prove a problem. If you are using a number of numbers—statistics, percentages, distances, et cetera—you may consider yourself to have a legitimate exception to this rule. Though numbers under one hundred are written out, page numbers, no matter their size, are not written out. Abbreviations, too, should be written out in formal writing, except, perhaps, for things like 12:00 a.m., A.D. 1931, or other, scholarly abbreviations (e.g., i.e., N.B., etc.). Be careful to avoid pressing the space bar twice when you don’t intend to do so (this is a more common error than you might think). After periods and colons (but not after semicolons), two spaces are fine. In the middle of a sentence, though, it looks silly, and I am apt to notice it and to point it out to you. Make certain that expressions are parallel in any list. If they aren’t, I am usually quick to point it out to you, to ask you to change it, and I draw two parallel lines in the margin to indicate the problem. Note, again, the intentional hypocrisy: the expressions ought to be parallel: to point, to ask, and to draw. One error that is all too common is the comma splice, it is awfully annoying. There’s some more intentional hypocrisy! The comma splice is easy to fix, though; a semi-colon can help the situation. Alternately, you could change the comma into a period and start a new sentence. The split infinitive is also a common mistake. Instead of saying “to quickly run,” avoid splitting the infinitive—to run—by moving the adverb to a more appropriate place: “to run quickly.” Yes, the writers of Star Trek were wrong: they should have Tuya 14 said, “to go boldly” or—and this strikes me as a bit weaker, though still a correct option— “boldly to go.” The following are examples of parenthetical citations in the MLA form. If you use any word from a source—any word, that is, unique to that source—it must be in quotation marks and cited. In Murder on the Yellow Brick Road, the hyphenated word “fez-like” provides an interesting contrast to “tinsel-town” (Kaminsky 1). The parenthetical citation consists of two things: The author’s last name and the page number. If you use the author’s name in the sentence, you only have to give me the page information. Kaminsky’s introduction is not all it could be: “Someone had murdered a Munchkin” (1). If you are referring to an idea the author expresses, but not to a specific sentence or word that the author uses, you still must cite it by giving me the author’s name and (if the idea comes from a specific page or group of pages) the page number. Eventually, the narrator discovers that the butler did it (Kaminsky 341). If you are not referring to a specific page, just give the author’s name. Many murder mysteries can be looked at with scorn (Kaminsky). Finally, if you are not referring to a specific page and you include the author’s name in the sentence, you don’t need to give me any further information. Kaminsky’s work has been translated into Japanese. Were I to quote more than four lines from a work, I would indent one full inch. This is twice as much as I normally indent for the beginning of a paragraph. By doing so, I am sure that no one will be confused as to whether my indention is a paragraph indention or a block quote indention. I would not use opening or closing quotation marks. The fact that I have indented one full inch serves the same purpose that quotation marks normally serve. If there is “a quote within ‘a quote within’ the citation,” I would follow the rules just demonstrated. “Double Tuya 15 quotations marks” within a block quote and single quotation marks within the double quotation marks. I would not alter the right-hand margin in any way. The citation for a block quote occurs outside the ending punctuation of the quote and without ending punctuation of its own. Block quotes are double-spaced, as is everything in the MLA form. (Hoop 341) All the examples in this paragraph are relatively unproblematic. They follow the rule for parenthetical citation, using the first major word in the works cited entry—which is usually the last name(s) of the author(s)—to point people to the precise point on the list of works cited to which they need to be directed. Because the works cited page is alphabetized, the essay’s readers (among which I include you) will simply look for Kaminsky among the Ks and Hoop among the Hs. In the next two examples, you would look among the Js for the work by Jones and among the Cs for the work with two authors. We must “Quote, quote, quote” (Jones 3). Otherwise, “nothing will serve as an example” (Clyde and Milbrook 117). Jones says, “Use the MLA form” (12). One trickier citing situation is the anonymous work. If no author is given, the entry on the works cited page will (usually) begin with the title. Using the first major word in the entry (the word by which you alphabetized the entry), point your professors to that, underlining it in the text of your essay if it’s underlined in the list of works cited and using quotation marks if it’s in quotation marks. You can find “examples of the first” (Examples 81). The second is, according to one source, “not that hard to find, either” (“Addendum” 12). Without even turning to the works cited page, you can tell that these quotations come from anonymous works, and that the first is either a book or a major work of some kind and the second is an article or some sort of minor work. Tuya 16 “Ah,” I hear you cry. “What if there are two or more works by the same author in the works cited list? Surely the MLA failed to consider that situation, and we’ll never be able to use even two sources by the same author: alas and alack.” You need not fear. Such a circumstance is not uncommon, although citing becomes just a bit trickier. Either you can make it clear in the body of your essay from which work you are citing—often an awkward task—or you can continue to point your audience to the appropriate point on the list of works cited by giving them the last name of the author and the first major word (again, the word by which you alphabetized the entry) on the works cited page. Contrast the statement “I have fourteen sports cars” (Smith, Me 129) with this: “I have never led an extravagant lifestyle” (Smith, “You” 41). From the very first entry, your audience members know that, among the Ss, they will find at least two works by a person named Smith, and that they should then look among the Ms in the Smith entries for the work in question. Go there yourself and see. You’ll also discover the “three-hyphens-or-threedashes-indicate-’this-work-begins-with-exactly-the-same-information-as-does-the-previousentry’” rule. Perhaps you are thinking, “But what if I’m writing an essay on Francis Schaeffer, and I intend to cite three works by him and one work by Edith Schaeffer? I’m stymied!” Stymied is exactly what you are not, though you may be temporarily perplexed. The easiest solution is to make sure that it’s clear in the body of your essay which Schaeffer is the Schaeffer in question. If that proves awkward or repetitious, point your readers to the proper point as best you can: after all, that’s the answer to the question “How shall we then live?” (F. Schaeffer 22). “Egad! How simple!” you cry. “But I want to cite Francis, Edith, and Franky Schaeffer, and two of the three share the same first initial.” Don’t worry—simply provide the full first name in such a case. Isn’t that right, Franky? “Oh, absolutely!” (Franky Schaeffer 69). Tuya 17 Section 6.4.7 will tell you what to do when you’re quoting someone who has been quoted in the work you’re citing. For example, if you’re writing a paper on Bob Dylan, you may want to quote part of an interview with him. If that’s the case, go ahead and quote him: “I usually listen to songs about things” (Dylan, qtd. in Futterman E1). The most perplexing issue of all, citationwise, is citing from internet resources. The MLA Handbook offers veritable scads of valuable information on how to put an internet resource into a list of works cited in section 5.6: “Citing Web Publications.” It then provides examples of in-text citations scattered in section 5.6.1. Here are some examples I’ve come up with; you can see how parenthetical citation works with the Works Cited page for web sites. Some sites do not provide an author; but they do provide other information by which they may be cited (“Phenomenon”). Some are different citations of the same URL because they cite different information from the same site (Pioch; Eyck). Some provide a good deal of information (Lancashire). And some are just good to think about (Dylan). I will now speak at greater length about what ought to be the most common kind of scholarly information found by means of the internet: the article published in print form in a scholarly journal and available by electronic means. The articles by Beck and MacDonald in the list of works cited for this document are examples of two different kinds of scholarly articles obtained by electronic means. The first part of each citation is extremely easy: simply cite it as if you had put your hands on the physical, print version of the article. As you obtained it electronically (and as your audience might conceivably do so as well), you should, out of common courtesy, let them know how and when you found it, and where, more specifically, you got the information you’re citing. For the MacDonald article, an article available in .pdf format—a format that looks exactly like the physical, print version of the article, including the Tuya 18 exact page numbers found in the original article—your job as its citer is remarkably easy. You simply provide the precise page number of each citation; your professor will have access to the same page numbers and will be able to find what you’re citing very easily. For example, you should know that MacDonald attempts to show that there is a distinct correlation between the journeys of Odysseus and the apostle Paul. His thesis is that “Luke’s intention in relating Paul’s shipwreck to those of Odysseus was to exalt Paul and his God by comparison” (88). If, however, you do not have the page numbers of the article (by which I do not mean the inclusive page numbers given in a citation—the 121-41 in the Beck article citation below)—if you have a textonly version of an article that does not indicate where one page stops and the next page begins, in other words—you cannot easily point your professors to the specific point in the article from which your direct quote comes. The good news is that you no longer have to count all the paragraphs, provide that number in the citation, and cite by paragraph number (see section 5.6.4). Your audience will bear the responsibility of finding precisely where the quote appears. For example, the author of the article without pagination in its electronic format argues with Parry’s theory about oral poetics, which, she feels, “relegated the epithets to the status of metrical filler material” (Beck). Most direct quotes will have page numbers; because this doesn’t supply page numbers, neither do you. Before we leave the topic of internet resources, we should address the question of providing URLs. Some URLs are only temporary: they expire soon after viewing. The article by Hernandez provides one such example. The actual URL I used to view the article follows in block quote format: <http://firstsearch.oclc.org/WebZ/FTFETCH?sessionid=sp04sw01-52699dl6icw4z-meknq2:entitypagenum=3:0:rule=100:fetchtype=fulltext:dbname=Wils Tuya 19 onSelectPlus_FT:recno=1:resultset=1:ftformat=PDF:format=BI:isbillable=TRUE: numrecs=1:isdirectarticle=FALSE:entityemailfullrecno=1:entityemailfullresultset =1:entityemailftfrom=WilsonSelectPlus_FT:>. Huge and seemingly-detailed though it is, that URL is utterly useless now. The MLA has recognized that you need not provide useless information. Within the citation itself, you simply indicate the database from which the article came (in this case, it came from Wilson Select Plus) and the word “Web” to indicate its point of origin. See the works cited page of this document for examples. Additionally, note that the MLA does say “You should include a URL as supplementary information only when the reader probably cannot locate the source without it or when your instructor requires it” (182). This instructor doesn’t require it, but other instructors may. Know your audience! When you provide inclusive page numbers in the MLA form, the MLA wants you to save ink when possible. That’s just another way they have of protecting the earth’s natural resources. For one- or two-digit numbers, the MLA asks for full disclosure: 1-9, 17-99, 54-55. But for three-, four-, and five-digit numbers, according to section 3.5.6, MLA desires only the last two digits, unless more are necessary: 104-09, 212-66, 354-55, 1,944-49, 199-279, 143-253. When you quote from poetry or drama, you should cite by line number rather than by page number. If you quote one line, you follow the same form as you would for an ordinary quote: “This is my play’s last scene” (Donne 1). If you quote two or three lines, you should place a space and slash and a space between each line: “This is my play’s last scene, here heavens appoint. / My pilgrimage’s last mile” (Donne 1-2). If you cite four or more lines of a poem, use block quote format (bearing in mind the absence of quotation marks in a block quote) and keep the line breaks of the poem: Tuya 20 This is my play’s last scene, here heavens appoint My pilgrimage’s last mile; and my race Idly, yet quickly run, hath this last pace, My span’s last inch, my minute’s latest point . . . . (Donne 1-4) These rules hold when citing epic poetry—although they do become a bit more complex. For works like The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Aeneid, and Paradise Lost, you need to provide the book and line number. The conclusion to The Odyssey is an optimistic one: “Both parties later swore to terms of peace / set by their arbiter, Athena” (XXIV.611-12). Achilles’ re-integration into society takes place at this point: “From the polished wagon / [Achilles’ men] lifted the priceless ransom brought for Hector’s corpse” (Homer, Iliad XXIV.677-78). Please note the logic of these citations. By the means of the last citation (that of The Iliad), you should be able to tell that there are two works by someone named Homer in the list of works cited for this document. If, in an essay you are writing, you are only citing one work by Homer—or if it’s clear (as it is in the “Both parties” quotation above) what work you’re citing, you need not provide as much information. The Odyssey begins with these words: “I sing” (I.1); it ends with the phrase “the form and voice of Mentor” (XXIV.614). Between the two, there are such questions as “What am I in for now?” (XIII.251), “What brings you to my island?” (V.92), and “Why so wakeful, / most forlorn of men?” (XX.36); additionally, there are a number of phrases in the work: “By vales and sharp ravines in Lakedaimon / the travelers drove to Meneláos’ mansion” (IV.1-2), “When primal Dawn” (II.1), and “When the young Dawn came bright into the East” (XVII.1), to name but a few. Tuya 21 When you cite Dante’s Divine Comedy, you should indicate, either in the text or in your citation—as long as it’s clear, it doesn’t matter which—the book, canto, and line number. Beatrice asks Dante, In the desire for me that was directing you to love the Good beyond which there’s no thing to draw our longing, what chains were strung, what ditches dug across your path that, once you’d come upon them, caused your loss of any hope of moving forward? (Purg. XXXI.22-27) For the answer to that question, we have to turn to Inferno: “The very sight of [the she-wolf] so weighted me / with fearfulness that I abandoned hope” (I.52-53). Paradiso may also reveal something about the nature of hope. As a disciple answering his master, prepared and willing in what he knows well, that his proficiency may be revealed, I said: “Hope is the certain expectation of future glory [. . . .]” (XXV.64-68) Note the use of quotation marks within a block quote in the example above. For quotes within quotes within the text of your essay, see this example: “I was still bent, attentive, over him, / when my guide nudged me lightly at the side / and said: ‘You speak; he is Italian’” (Inf. XXVII.31-33). Another example follows: “‘Sperent in te’ was heard above us” (Par. XXV.98). The rules for citing poetry apply for citing drama, although you must usually provide the act and scene in addition to the line number. You may modernize Roman numerals if you wish, Tuya 22 but such modernization is not mandatory. Indeed, I think Roman numerals look classier than Arabic numbers. Just be consistent. In Thomas Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy, Hieronimo has this to say: “Why, ha, ha, ha! Farewell, good, ha, ha, ha!” (III.xi.31). To this remarkable statement, the second Portingale replies, “Doubtless this man is passing lunatic, / Or imperfection of his age doth make him dote” (III.xi.32-33). Should you wish to cite a stage direction, give the number for the line that proceeds it and follow it with the initials s.d. Horatio’s death is too much for Isabella to bear, as we can see from the fact that “She runs lunatic” (III.viii.5.s.d.). The rules for block quotes are the same as those for citing poetry. One passage that T. S. Eliot draws from is Hieronimo’s polysemous utterance to Lorenzo and Balthazar: Why then I’ll fit you; say no more. When I was young I gave my mind And plied myself to fruitless poetry: Which though it profit the professor naught, Yet is it passing pleasing to the world. (IV.i.70-74) When a play has no act number (or, alternately, no scene number), provide what you can. Faustus says, “O would I had never seen Wittenberg” (13.19 [I provide Arabic numbers in this case because the Norton Anthology uses them; it would be equally correct to put “xiii.19”—note the lowercase Roman numerals for scene number]). John Dryden’s All for Love has no scene numbers, so you would cite it according to act number. Antony declares, “I will be justified in all I do / To late posterity, and therefore hear me” (II.251-52). Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene requires a wonderfully complex—though quite logical—mode of citation. Books are cited by uppercase Roman numerals, cantos by lowercase, stanzas and line numbers by Arabic numbers. Thus, “A Gentle Knight was pricking on the Tuya 23 plaine” (I.i.1.1) begins the story of the Redcrosse Knight while “Suffice it heare by signes to understand / The usuall joyes at knitting of loves band” (I.xii.40.4-5) comes near the end. The advantage to this mode of citation is its clarity: once you have established the book and canto you’re addressing, you can provide abbreviated citations, and your audience will still know what you’re talking about. The theme of love in Canto xii of Book One can be seen in many places (28.8-9, 30.1-2). Book One concerns itself with the theme at large (v.12, viii.12.8, ix.26). Frequently, we cite passages from the Bible (with a capital “B”); these are biblical passages (with a lowercase “b”). All you need to provide in the paragraph is the citation. This can take a number of forms. For example, John 11:35 tells us that “Jesus wept.” Later in the Bible, we are told that “we should love one another” (1 John 3:11b). Your professors will look to the works cited page to find out what version you are using. See section 6.4.8 of the handbook—or the works cited page of this handout—for an example to follow. If you are using multiple translations in the same work, it is probably best to indicate so in the text of the essay. Much plagiarism occurs in the process known as “direct paraphrase.” It takes place when someone uses the author’s words and cites the author and, perhaps, the page number from which the words are taken but neglects to put the author’s words in quotation marks. This sort of plagiarism is particularly virulent. To avoid even accidental plagiarism, be sure that any word which comes from an author and not from yourself is in quotation marks and cited. This is true of single words, phrases, and sentences. All must be in quotes and appropriately cited. Some of the suggestions in this document may apply to one professor’s desires and not to another’s. Your job, as an intelligent writer, is to know your audience. Some professors may, for example, object to the first person in essays—for them, you should avoid the first person. Some disciplines demand that the passive voice be employed—this should be done, in those Tuya 24 cases. But many of the statements in this document fall into the category of “rules”—to be followed whatever the audience—unless you have considered them critically and have a definite and discernable purpose for breaking them. Use your keen judgement and ask questions of your professors. And if you’re wondering just how important the conventions of the MLA and the demands of your professor are, I point you toward a recent article by Al Kamen in The Washington Post. An organization for the treatment of drug and alcohol abuse was declined a request for $600,000 for the following reason: “Your application has been examined by review staff from the Division of Extramural Program Management,” [application reviewer Diane McMenamin] wrote, “and was judged to be non-conforming for the following reason: (1) Your application does not conform to the instructions for format as stated in Part II of the [grant application form] in that applications have ‘conventional border margins of 1 inch.’” (A29) The exactitude of your margins may not result in such a substantial financial loss, but errors in margins will reduce your grades and prevent you from becoming the fully-developed human being you are meant to become. I’ve never been good with conclusions. Tuya 25 Works Cited “Addendum to the Notes on the Writing of Effective Prose.” Writing Today 12 November 2000: 12. Print. Aeschylus. The Oresteia. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1979. Print. Beck, Deborah. “Speech Introductions and the Character Development of Telemachus.” The Classical Journal 94 (1998-1999): 121-41. N. pag. Wilson Select Plus. Web. 3 September 2003. Beowulf. Trans. R. K. Gordon. New York: Dover, 1992. Print. Block, Elizabeth. “Clothing Makes the Man: A Pattern in the Odyssey.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 115 (1985): 1-11. JSTOR. Web. 9 September 2003. Chaucer, Geoffrey. The Canterbury Tales. Trans. A. Kent Hieatt and Constance Hieatt. New York: Bantam, 1964. Print. Clyde, Andrew, and Marielle Milbrook. “All About MLA.” Shakespeare Quarterly 121 (2001): 13-194. Print. Dante. Inferno. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam, 1982. Print. ———. Paradiso. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam, 1984. Digital Dante. November 1997. N. pag. Institute for Learning Technologies. Web. 2 February 2003. ———. Purgatorio. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Bantam, 1984. Print. Dilworth, Thomas. “The Fall of Troy and the Slaughter of the Suitors: Ultimate Symbolic Correspondence in The Odyssey.” Mosaic 27 (1994): 1-24. N. pag. Periodical Abstracts. Web. 9 September 2003. Donne, John. “Holy Sonnet VI.” Selected Poems. New York: Dover, 1993. 61. Print. Tuya 26 Dostoevsky, Fyodor. The Brothers Karamazov: The Constance Garnett Translation Revised by Ralph E. Matlaw: Backgrounds and Sources: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Ralph E. Matlaw. Trans. Constance Garnett. New York: W. W. Norton, 1976. Print. Dryden, John. All for Love. Ed. N. J. Andrew. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000. Print. Dylan, Bob. “Sugar Baby.” bobdylan.com. Columbia Records, 2001. Web. 29 September 2003. Examples Aplenty: Although this Work is Anonymous and has an Extremely Long Title, its First Word is Enough for the Parenthetical Citation. New York: Wilson, 1991. Print. Eyck, Jan van. The Arnolfini Marriage. Webmuseum, Paris. N.p., 2 July 2003. Web. 13 March 2004. Futterman, Ellen. “Times They are a Changin’ . . . : Dylan Speaks.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 7 April 1994: E1+. Print. Gibaldi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 7th ed. New York: MLA, 2009. Print. Hernandez, Pura Nieto. “Odysseus, Agamemnon and Apollo.” The Classical Journal 97 (2002): 319-34. Wilson Select Plus. Web. 9 September 2003. The Holy Bible: New International Version. Colorado Springs: International Bible Society, 1984. Print. Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin, 1998. Print. ———. The Odyssey. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998. Print. Hoop, Ally O. Hamster, Goldfish, Rocking Chair: The Necessary Trio. Paris: Je Ne Sais Pas Press, 1932. Print. Tuya 27 Jones, Keith. Notes on the Writing of Effective Prose: Don’t use Stilted Titles Like This One. New York: Wilson, 1991. Print. Kamen, Al. “Dean’s X-Files.” The Washington Post 5 December 2003, final ed.: A29. Print. Kaminsky, Stuart. Murder on the Yellow Brick Road. New York: Penguin, 1979. Print. Kyd, Thomas. The Spanish Tragedy. Ed. J. R. Mulryne. New York: W. W. Norton, 1989. Print. Lancashire, Ian. “Online Editor’s Introduction.” Representative Poetry On-Line. 3.0. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 September 2003. MacDonald, Dennis R. “The Shipwrecks of Odysseus and Paul.” New Testament Studies 45 (1999): 88-107. Ebscohost. Web. 3 February 2003. Marlowe, Christopher. Doctor Faustus. The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Sixteenth Century; The Early Seventeenth Century. 7th ed. Vol. 1B. Gen. ed. M. H. Abrams. Associate Gen. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000. 991-1023. Print. “Phenomenon.” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. James Fieser. N. p., 1998. Web. 29 September 2003. Pioch, Nicolas. “The Arnolfini Marriage.” Webmuseum, Paris. N. p., 2 July 2003. Web. 29 September 2003. Rosen, Nathan. “Style and Structure in The Brothers Karamazov (The Grand Inquisitor and the Russian Monk).” The Brothers Karamazov: The Constance Garnett Translation Revised by Ralph E. Matlaw: Backgrounds and Sources: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Ralph E. Matlaw. New York: W. W. Norton, 1976. 841-51. Print. Schaeffer, Edith. Christianity is Jewish. Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1975. Print. Tuya 28 Schaeffer, Francis A. How Should we then Live?: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture. Old Tappan, N.J.: F. H. Revell, 1976. Print. Schaeffer, Franky. Dancing Alone: The Quest for Orthodox Faith in the Age of False Religion. Brookline: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1994. Print. Scodel, Ruth. “The Removal of the Arms, the Recognition with Laertes, and Narrative Tension in The Odyssey.” Classical Philology 93 (1998): 1-17. Academic Search Premier. Web. 9 September 2003. Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. New York: Dover, 1992. Print. Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. New York: Dover, 1994. Print. Singleton, Charles S. “The Vistas in Retrospect.” MLN 81 (1966): 55-80. JSTOR. Web. 3 March 2003. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Patience, and Pearl. Trans. Marie Borroff. New York: W. W. Norton, 2001. Print. Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Sixteenth Century; The Early Seventeenth Century. 7th ed. Vol. 1B. Gen. ed. M. H. Abrams. Associate Gen. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. New York: W. W. Norton, 2000. 628-863. Print. Smith, W. C. Me and my Shadow, Walking down the Avenue. New York: Wilson, 1991. Print. . “You have Misjudged me: I am a Nice Guy!” Philanthropy 12.4 (1995): 133-57. Print. Wasiolek, Edward. “The Brothers Karamazov: Idea and Technique.” The Brothers Karamazov: The Constance Garnett Translation Revised by Ralph E. Matlaw: Backgrounds and Tuya 29 Sources: Essays in Criticism. Ed. Ralph E. Matlaw. New York: W. W. Norton, 1976. 813-21. Print.