UTI VUR

advertisement

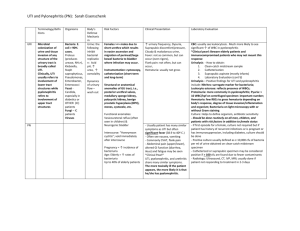

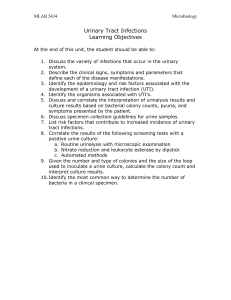

UTI/VUR DR Badi AlEnazi Consultant pediatric endocrinology and diabetologest • Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common pediatric infections. It distresses the child, concerns the parents, and may cause permanent kidney damage. Prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of a febrile UTI may prevent acute discomfort and, in patients with recurrent infections, kidney damage. Epidemiology The incidence of UTIs varies based on age, sex, and gender. It was found that the overall prevalence of UTI in infants presenting with fever was 7.0%. the rates in girls were as follows: 0-3 months - 7.5% 3-6 months - 5.7% 6-12 months - 8.3% >12 months - 2.1% In febrile boys less than 3 months of age: 2.4% of circumcised boys . 20.1% of uncircumcised boys . The 2 broad clinical categories of UTI are: pyelonephritis (upper UTI) cystitis (lower UTI). Etiology Bacterial infections are the most common cause of UTI, with E coli being the most frequent pathogen, causing 75-90% of UTIs. Other bacterial sources of UTI include the following: •Klebsiella species •Proteus species •Enterococcus species •Streptococcus group B, especially among neonates •Pseudomonas aeruginosa •Fungi (Candida species) may also cause UTIs •Adenovirus is a rare cause of UTI and may cause hemorrhagic cystitis. Risk factors Susceptibility to UTI may be increased by any of the following factors: Alteration of the periurethral flora by antibiotic therapy Anatomic anomaly Bowel and bladder dysfunction Constipation Circumcision and UTI • For male infants, neonatal circumcision substantially decreases the risk of UTI. It was found that during the first year of life, the rate of UTI was 2.15% in uncircumcised boys, versus 0.22% in circumcised boys. Risk is particularly high during the first 3 months of life. Diagnosis The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) criteria for the diagnosis of UTI in children 2-24 months: are the presence of pyuria and/or bacteriuria on urinalysis and of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of a uropathogen from the quantitative culture of a properly collected urine specimen. Urine specimen collection • A midstream, clean-catch specimen may be obtained from children who have urinary control. In the infant or child unable to void on request, the specimen for culture should be obtained by suprapubic aspiration or urethral catheterization. • Suprapubic aspiration is also the method of choice for obtaining urine from uncircumcised boys,from girls with tight labial adhesions, and from children of either sex with clinically significant periurethral irritation. • Culture of a urine specimen from a sterile bag attached to the perineal area has a false-positive rate so high that this method of urine collection is not suitable for diagnosing UTI. However, a culture of a urine specimen from a sterile bag that shows no growth is strong evidence that UTI is absent. Urinalysis • Urinalysis alone is not sufficient for diagnosing UTI. Children with unexplained fever or voiding symptoms may have positive urinary cultures even when abnormal findings are not evident on complete urinalysis. Blood studies • Hematologic studies do not tend to help in the diagnosis of UTIs, although they should be obtained in patients who appear ill. Obtain a complete blood count (CBC) and basic metabolic panel for children with a presumptive diagnosis of pyelonephritis. Perform blood cultures in febrile infants and older patients who are clinically ill, toxic, or severely febrile. Evaluation of renal function • Renal function can be measured by serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels; both may be elevated in severe disease. Electrolyte abnormalities may be present. Ultrasonography Urinary ultrasonography is useful in: excluding obstructive uropathy identifying a solitary or ectopic kidney moderate renal damage caused by pyelonephritis. Performance of voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) after a first febrile UTI may be indicated if: renal and bladder ultrasonography reveal hydronephrosis, scarring, obstructive uropathy, or masses complex medical conditions are associated with the UTI. • Children who respond to treatment for a UTI but afterwards demonstrate an abnormal voiding pattern may need to undergo an evaluation for voiding dysfunction. This evaluation may include standard VCUG. • VCUG is also recommended after a second episode of febrile UTI. There is some concern, however, that without VCUG after the first documented febrile UTI, some cases of significant reflux disease will be missed symptoms Children aged 0-2 months usually do not have symptoms localized to the urinary tract. UTI is discovered as part of an evaluation for neonatal sepsis. Neonates with UTI may display the following symptoms: Jaundice Fever Failure to thrive Poor feeding Vomiting Irritability Infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years Infants with UTI may display the following symptoms: Poor feeding Fever Vomiting Strong-smelling urine Abdominal pain Irritability Children aged 2-6 years Preschoolers with UTI can display the following symptoms: Vomiting Abdominal pain Fever Strong-smelling urine Enuresis Urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency) Children older than 6 years and adolescents School-aged children with UTI can display the following symptoms: Fever Vomiting, abdominal pain Flank/back pain Strong-smelling urine Urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency) Enuresis Incontinence Physical Examination • • • • • • Costovertebral angle tenderness Abdominal tenderness to palpation Suprapubic tenderness to palpation Palpable bladder Dribbling, poor stream, or straining to void Examine the external genitalia for signs of irritation, pinworms, vaginitis, trauma Differential diagnosis Conditions that can produce the symptoms of urinary tract infection (UTI) include the following: Epididymitis Orchitis Prostatitis Urethritis Urolithiasis Bladder and bowel dysfunction Treatment Criteria of Hospital Admission Usual indications for hospitalization and/or parenteral therapy include: Age <2 months Clinical urosepsis (eg, toxic appearance, hypotension, poor capillary refill) Immunocompromised patient Vomiting or inability to tolerate oral medication Lack of adequate outpatient follow-up (eg, no telephone, live far from hospital, etc) Failure to respond to outpatient therapy Empiric therapy • Early and aggressive antibiotic therapy (eg, within 72 hours of presentation) is necessary to prevent renal damage. Delayed therapy has been associated with increased severity of infection and greater likelihood of renal damage .Decisions regarding the initiation of empiric antimicrobial therapy for UTI are best made on a case-by-case basis based upon the probability of UTI, which is determined by demographic and clinical factors We suggest that empiric antimicrobial therapy be initiated immediately after appropriate urine collection in children with suspected UTI and a positive urinalysis. This is particularly true for children who are at increased risk for renal scarring if UTI is not promptly treated, including children who present with: •Fever (especially >39°C [102.2°F] or >48 hours) •Ill appearance •Costovertebral angle tenderness •Known immune deficiency •Known urologic abnormality parenteral antibiotic therapy The diagnosis in infant with a febrile UTI is usually based on fever and on positive results from a urine specimen obtained by catheterization. Infants with such findings are usually hospitalized and receive parenteral antibiotic therapy Drug Dosage and Route Ceftriaxone 50-75 mg/kg/day IV/IM as a Do not use in infants < 6 wk single dose or divided q12h of age; parenteral antibiotic with long half-life; may displace bilirubin from albumin Cefotaxime 150 mg/kg/day IV/IM divided q6-8h Note: IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; q = every. Comment Safe to use in infants < 6 wk of age; used with ampicillin in infants aged 2-8 wk Drug Dosage and Route Ampicillin 100 mg/kg/day IV/IM divided q8h Gentamici Term neonates < 7 days: 3.5-5 n mg/kg/dose IV q24h Comment Used with gentamicin in neonates < 2 wk of age; for enterococci and patients allergic to cephalosporins Monitor blood levels and kidney function if therapy extends >48 h Infants and children < 5 years: 2.5 mg/kg/dose IV q8h or single daily dosing with normal renal function of 5-7.5 mg/kg/dose IV q24h Children ≥5 y: 2-2.5 mg/kg/dose IV q8h or single daily dosing with normal renal function of 5-7.5 mg/kg/dose IV q24h Note: IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; q = every. Antibiotic Agents for the Oral Treatment of Urinary Tract Infection Protocol Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP) Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid Daily Dosage 30-60 mg/kg SMZ, 6-12 mg/kg TMP divided q12h 20-40 mg/kg divided q8h Cephalexin Cefixime Cefpodoxime Nitrofurantoin* 50-100 mg/kg divided q6h 8 mg/kg q24h 10 mg/kg divided q12h 5-7 mg/kg divided q6h *Nitrofurantoin may be used to treat cystitis. It is not suitable for the treatment of pyelonephritis, because of its limited tissue penetration. Complication Complication of pyelonephritis : focal inflammation of the kidney (focal pyelonephritis) or renal abscess. scar formation. Approximately 10-30% of children with UTI develop some renal scarring; however, the degree of scarring required for the development of long-term sequelae is unknown. Long-term complications of pyelonephritis are hypertension, impaired renal function, and end-stage renal disease. VESICOURETERAL REFLUX (VUR) • Definition Is the retrograde passage of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary tract. • prevalence VUR is present in approximately 1 percent of newborns . The prevalence is high in children with febrile and non-febrile urinary tract infections (UTIs), ranging from 30 to 45 percent . There is significant ureteral dilation and tortuosity Left sided grade V reflux Massive reflux grossly dilates the collecting system. All the calyces are blunted with a loss of papillary impression VUR is divided into two categories : • Primary VUR : the most common form of reflux, is due to incompetent or inadequate closure of the ureterovesical junction (UVJ), which contains a segment of the ureter within the bladder wall (intravesical ureter). In primary VUR, failure of this anti-reflux mechanism is due to the shortening of the intravesical ureter • Secondary VUR : is a result of abnormally high pressure in the bladder that results in failure of the closure of the UVJ during bladder contraction Secondary VUR is often associated with anatomic (eg, posterior urethral valves) or functional bladder obstruction (eg, dysfunctional voiding and neurogenic bladder) DIAGNOSIS • The diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is based upon the demonstration of reflux of urine from the bladder to the upper urinary tract by either contrast voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) or radionuclide cystogram (RNC). Although there is increased radiation exposure with VCUG compared with RNC, VCUG provides greater anatomic detail. • Grade I – Reflux only fills the ureter without dilation. Left sided grade I reflux Grade II – Reflux fills the ureter and the collecting system without dilation Grade III – Reflux fills and mildly dilates the ureter and the collecting system with mild blunting of the calyces Grade IV – Reflux fills and grossly dilates the ureter and the collecting system with blunting of the calyces. Some tortuosity of the ureter is also present. Grade V – Massive reflux grossly dilates the collecting system. All the calyces are blunted with a loss of papillary impression, and intrarenal reflux may be present. There is significant ureteral dilation and tortuosity. CLINICAL FINDINGS • Prenatal presentation The presence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is suggested by the finding of hydronephrosis on prenatal ultrasonography. In fetuses with prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis, the reported prevalence of VUR ranges from 10 to 40 percent prenatal hydronephrosis was defined as a renal pelvic diameter (RPD) ≥4 mm during the second trimester and ≥7 mm during the third trimester Postnatal presentation Postnatal diagnosis of VUR usually is made after an episode of UTI, and less commonly after family screening of an index case. Children with a febrile UTI have a higher risk for abnormalities of the genitourinary tract, including VUR and obstructive uropathy Management of VUR medical therapy The following are single daily doses of commonly used antimicrobial agents: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) or TMP alone − Dosing is based on TMP at 2 mg/kg Nitrofurantoin − 1 to 2 mg/kg Cephalexin − 10 mg/kg Ampicillin − 20 mg/kg Amoxicillin − 10 mg/kg medical therapy • Antibiotic prophylaxis is usually continued until there is spontaneous resolution of VUR or surgical correction. CHOICE OF THERAPY • Grades III to V at risk for recurrent pyelonephritis and possible renal scarring, and potentially chronic kidney disease (CKD • All patients with grades III to V VUR regardless of age receive antibiotic prophylaxis • Surgical correction is considered and discussed with the family for children with the following conditions: • Grade IV/V reflux in children older than two or three years of age with persistent high-grade reflux or who have breakthrough infection • Children who fail medical therapy and have breakthrough infections, who have significant side effects from continuous prophylactic antibiotic coverage, or whose families are not compliant with a long-term medical regimen. Cont.. • Grade I and II Children with grade I or II reflux are at a lower risk for pyelonephritis and renal scarring, and are more likely to have spontaneous resolution of their VUR.