File - Suzanne C. Peterson, MLIS

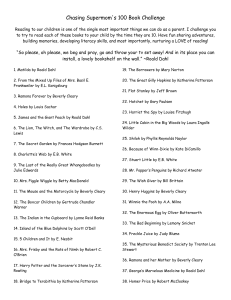

advertisement

THE KLICKITAT STREET JOURNAL Suzanne Peterson, Editor EXPLORING THE WORKS OF BEVERLY CLEARY May 5, 2013 NEWBERY WINNING AUTHOR BEVERLY CLEARY is one of the most successful American children’s authors, having sold over 90 million copies of her books worldwide. She has won numerous literary awards, including the 1984 Newbery Medal for Dear Mr. Henshaw and Newbery Honors for Ramona and Her Father and Ramona Quimby, Age 8. Cleary is the creator of such beloved characters as Henry Huggins, Ellen Tebbits, and Ralph S. Mouse. Most of them live on or near Klickitat Street, a real street from Cleary’s childhood neighborhood in Oregon. None have been more popular and enduring than Ramona Quimby. The star of eight books, which have been constantly in print since Beezus and Ramona was first published in 1955, Ramona has charmed multiple generations of readers for more than 50 years. 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children THE WORLD OF RAMONA NEWS From Minor Character. To Breakout Star IT’S HARD TO believe, but Ramona’s early role on Klickitat Street was a minor one, as the pesky younger sister of Henry Huggins’ pal Beezus. Her stubborn determination to be included and her vivid imagination led to such misadventures as locking Henry inside his clubhouse and blackmailing him into teaching her the password. Beverly Cleary is the first to admit that she never planned on Ramona becoming the star. “I hadn’t really intended to write so much about her, but there she was. She kept hanging around, and I kept having Ramona ideas,” said Cleary. (Harper Collins) Those ideas led to first an expanded role in Beezus and Ramona, then a starring turn in Ramona The Pest. By 1999 there were eight books in the Ramona series, spanning a timeframe of nearly 50 years. Above: Originally, Ramona had been conceived as a minor character in books about Henry Huggins and Beezus Quimby. “I’ve done what I started to do,” Cleary stated, “to write books that children would want to read, books that would let them enjoy reading. I want them to discover that reading is more . than something they have to do in school. Ramona and the others are just the sort of kids who lived in my neighborhood in Portland. Everything in the Ramona and Henry books could have happened in Portland and probably did.” (Staino, 2010) 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children ENCOURAGING LITERACY NEWS . AND READ! DROP EVERYTHING D.E.A.R. stands for “Drop Everything and Read,” a national month-long celebration of reading designed to encourage kids to read for pleasure. Letters from children describing their schools’ D.E.A.R. activities inspired Cleary to incorporate this project into Ramona Quimby, Age 8. Since then, D.E.A.R. has grown in popularity and scope, and nationwide D.E.A.R. programs are now held annually on April 12th, in honor of Beverly Cleary’s birthday. Above: Cleary was inspired by letters from children describing D.E.A.R. activities to incorporate the project into Ramona Quimby, Age 8. A RECURRING theme throughout the Ramona books is Ramona’s eagerness to learn to read. From her first day of kindergarten, she thinks in terms of “the literary myth.” This theory suggests that at a young age, Ramona “has internalized the idea that learning to read and write will lead to personal, social, and economic improvement.” (Benson, 1999) This is presented in the books in a much less heavy. handed manner, however, as Ramona simply expects that acquiring these skills will help her to “catch up with Beezus” (Ramona the Pest) and the other big kids in the neighborhood. Her enthusiasm for reading persists throughout the series, even as she encounters frustrations such as boring text like “Tom and Becky and their dog Pal and their cat Fluff who could run, run, run” (Ramona the Brave) and her teachers’ insistence on correct spelling. NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children As Ramona’s reading skills improve, she acquires a feeling of power. “Words leaped out at her from newspapers, signs, and cartons. Crash, highway, salt, tires. The world was suddenly full of words that Ramona could read.” (Ramona the Brave) By third grade, Ramona is able to judge a book’s literary merit, critiquing the story of an elderly couple adopting a stray cat as inaccurate, because “cream cost too much…the most the old people would give a cat was half-and-half.” (Ramona Quimby, Age 8) Books are a source of both enjoyment and comfort, as when she longs for her “Betsy book” while anxiously awaiting her parents, who are late to pick her up from the babysitter. (Ramona and Her Mother) The best part of third grade is “Sustained Silent Reading,” because “she was not expected to write lists of words she did not know… [Her teacher] did not expect the class to write summaries of what they read either, so she did not have to choose easy books to make sure she would get her summary right.” (Ramona Quimby, Age 8) In the fourth grade, Ramona shares her love of books by reading aloud to her new baby sister: “she enjoyed the rhymes and read with expression and dramatic gestures.” (Ramona’s World) The joy of reading for pleasure resonates with children discovering this love for themselves through Cleary’s books. Writing, too, is a way in which Ramona establishes her independence and “catches up” with Beezus and the other kids on Klickitat Street. She achieves her first reward from writing in Ramona the Brave, when she writes a note for her mother that simply reads “Come. here, Mother. Come here to me.” Her mother responds by appearing in Ramona’s bedroom upon returning home from Open School Night. The note “effectively summons the family support the anxious Ramona needs.” (Benson, 1999) Perhaps the biggest payoff of learning to write comes in Ramona and her Father. Mr. Quimby’s smoking habit inspires Ramona and Beezus to launch an anti-tobacco campaign, papering the household with homemade posters reading “Smoking is Hazardous to Your Health,” “Stop Air Pollution,” and “Cigarettes Start Forest Fires.” In addition to learning to spell new and bigger words, Ramona’s determined application of her writing skills eventually lead to her father agreeing to quit. “The success of the campaign, impossible without her writing skills, demonstrates to her and readers the power of literacy.” (Benson, 1999) Her reading and writing skills have not only given her pleasure, but the power to effect change within her family, and to feel like an equal. It’s an appealing example for early readers to follow. . 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children “A WONDERFULY REAL LITTLE GIRL” NEWS MUCH LIKE Ramona Quimby .herself, as a child Beverly Cleary eagerly awaited starting school so she could learn to read. Once in the classroom, however, she was disappointed. The books available to children bore little relation to Cleary’s middleclass life in Portland, Oregon. “I longed for funny stories about the sort of children who lived in my neighborhood,” Cleary wrote in her memoir, My Own Two Feet. Unable to find them, she decided that when she grew up she would write them herself. (Paul, 2011) And she did. Cleary set most of her books on Klickitat Street, a real street near her childhood home. The situations her characters find themselves in are ones that real kids experience: finding a stray dog, getting a paper route, arguing with their best friends. More importantly, the characters themselves are just like the children who read about them. Cleary has a gift for getting right inside the mind of a child and understanding the kinds of things they think about. One of the best examples comes in Ramona the Pest when Ramona’s kindergarten teacher reads aloud to the class from Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel. While listening to the story, a question that has always bothered her occurs to Ramona: Above: “I am too a Merry Sunshine!” Ramona as she appears in Beezus and Ramona, published in 1955. “Miss Binney,” Ramona asked, “I want to know – how did Mike Mulligan go to the bathroom when he was digging the basement of the town hall?” NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children The question stops the poor teacher in her tracks, but the rest of the children await the answer with curious anticipation. It is this scene in a nutshell which “wholly captures children’s persistent need to relate what they read to their own lives.” (Paul, 2011) Cleary states that one of her own children asked her the same question about Mike Mulligan, prompting her to include it in the book. Similarly, other episodes from her books come from her own childhood memories, and those of her children. When creating her stories about Ramona and the other kids on Klickitat Street, Cleary always remained mindful of her former writing professor’s advice to make them about “universal human experience grounded in the minutiae of ordinary life.” (Paul 2011). Her stories address concerns that all children have, and have continued to have throughout the decades since Ramona first appeared in print. Haven’t all children wanted to pull every tissue out of the box? Or delighted in a new pair of rain boots or got angry at the kid who copied their art project – these are the kinds of things that weigh on children’s minds, and Cleary takes them seriously, even as she allows for the humor that such concerns can cause. It is her understanding – and more importantly, her respect - for the inner workings of a young child’s mind that make her books so enduringly popular. Children recognize themselves in Ramona, and rejoice in finding a character to whom they can relate. . 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children RAMONA’S TIMELESS APPEAL Above: Cleary utilized two different illustrators for the majority of her works. Louis Darling drew the original version of Ramona, left, in books published in the 1950s and 60s. Alan Tiegreen took over with the books of the 1970s through the rest of the series, creating Ramona’s look shown in the center. When the books were reprinted in the early 21st century, Tracy Dockray updated the illustrations for the entire series. NEWS . HOW CAN a series of books, first published more than 50 years ago, remain just as popular and keep children as entertained as ever in this age of text messaging and video games? When she first began writing, Cleary’s approach was to keep the books from becoming dated by resolving to “ignore all trends.” (Schwarz, 2011) For the most part, she held firm to her original goal, avoiding pop culture references and topical storylines that would set her stories firmly into any specific time period. It cannot be denied, however, that the world she created on Klickitat Street is a thing of the past. Cleary’s characters explore the neighborhood and walk to school unsupervised by adults. Most of the children have stay at home mothers who bake cookies (although in later books, Cleary gives a nod to progressiveness by having Ramona’s mother get a part-time job to help the family make ends meet). The girls wear dresses to school and play hopscotch, while the boys ride bikes without helmets and build clubhouses in their backyards. Ice cream cones cost a nickel; you could get several pieces of bubblegum for a penny, and the tooth fairy left a dime under your pillow. Any child of today’s high-tech world will recognize that these stories are set in an era that is long gone. But it doesn’t seem to matter. Today’s young readers “have little difficulty finding the stories resonant, though the protagonists, NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children situations, and even values fail to conform to current standards.” (Schwarz, 2011) In 1995, Barbara Chatton of Horn Book Magazine spoke to a group of fourth graders who had identified Beverly Cleary among their favorite authors (in a group that also included R.L. Stine, author of the Goosebumps books). When discussing the books, Chatton found that the children most often noticed the discrepancies in things like the price of candy and ice cream. When specifically asked to identify other things that differed from their own experience, the kids pointed to the fact that their schools do not have students like Henry Huggins as crossing guards, but police officers or senior volunteers; they do not have little trash cans in the schoolyard like the one Ramona hid behind to avoid a substitute teacher in Ramona the Pest, but dumpsters in areas where they are not allowed to go; and there is no such thing as Show and Tell in most classrooms. However, none of these things were too difficult to figure out, and they did not detract from the children’s enjoyment of the stories. When asked what they liked most about the Ramona books, many of the children told Chatton that they liked them because “they aren’t sad.” Others mentioned that they are funny, and perhaps most importantly, that they like the characters “because they did a lot of the things kids do.” And this is a major factor in the books’ enduring success. Throughout the series, Ramona’s biggest concerns are universal ones: she strives to please her teachers, longs for a bicycle and a. best friend, argues with her older sister and struggles with the challenges of growing up. These are issues that resonate with elementary school children today. Times have changed, but at their core, children have not. “Children want the same things my generation wanted,” Beverly Cleary explains. “A home with loving parents, and children to play with in safe neighborhoods [and] funny books about children like themselves.” (Paul, 2011) It is a wish that Beverly Cleary has fulfilled for more than fifty years. RAMONA GOES HOLLYWOOD! PERHAPS the greatest testament to the enduring appeal of Ramona Quimby is the fact that a major Hollywood movie, Ramona and Beezus, was made in 2010. The film was a success with critics and with audiences of multiple generations of readers who grew up with the Ramona books. Ramona and Beezus starred Joey King and Selena Gomez in the title roles. Cleary herself was pleased with the movie portrayal. NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children THE HUMOR OF RAMONA . “ALTHOUGH CHILDREN long for laughter, too often… adults feel the purpose of any book is to teach... Children would learn so much more if they were allowed to relax, enjoy a story, and discover what it is they want or need from books. They might even learn to enjoy reading, especially if they found in the early grades humorous books that make them laugh.” (Smith, 2006). This has firmly remained Cleary’s philosophy throughout the decades in which she has written for children. Humor is a staple of all of her stories, even when she touches on plotlines of a more serious nature, such as Ramona’s worries about her father’s health as a chronic smoker in Ramona and Her Father. Determined to make him quit, she papers the walls of the Quimby household with homemade “No Smoking” signs – but makes her letters too large, resulting in signs that read: NO SMO KING - prompting Mr. Quimby to infuriate Ramona by inquiring, “Say, who is this Mr. King?” She angrily tears down the signs and begins again. Above: An updated illustration of the Quimby family, from the 2002 reprint of Ramona and Her Father, reacting to one of Ramona’s big ideas gone wrong. It’s hard to imagine a child (or adult) anywhere who won’t find episodes in the Ramona books to make them laugh out loud. Can anyone really keep a straight face when she cracks what she thinks is a hard-boiled egg (which turns out to be raw) on her head (Ramona Quimby, Age 8), squeezes an entire tube of 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children toothpaste into the bathroom sink (Ramona and Her Mother), or crowns herself with a tiara made of burs, resulting in an emergency home haircut? (Ramona and Her Father) One of the funniest, most often recalled scenes is in Ramona the Brave, when a frustrated, tearful Ramona stamps her foot and shouts “I’m going to say a bad word!” Her family falls silent, and her mother gives her permission to say the bad word if it will make her feel better: “Ramona clenched her fists and took a deep breath. “Guts!” she yelled. “Guts! Guts! Guts!” There. That should show them.” (Ramona the Brave) The reader can hardly help but join in as the rest of the family dissolves into helpless laughter. Still, her parents quickly recover and comfort her. Beezus shares some experiences from her own earlier childhood when their parents laughed at her when she was being serious, consoling Ramona with her support. After everyone makes up, Ramona asks for clarification: “Isn’t guts a bad word?” Mrs. Quimby thought for a moment. “I wouldn’t say it’s exactly a bad word. It isn’t the nicest word in the world, but there are worse words.” Ramona wondered what could be worse than guts. NEWS . This episode is perhaps the most perfect example of Cleary’s affectionate humor. Despite laughing at her, Ramona’s family is quick to rally around her and explain the joke, even providing their own examples of being misunderstood. “She’s deeply respectful of her characters – nobody gets a laugh at the expense of another…I think kids appreciate that they’re on a level playing field with adults.” (Paul, 2011) NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children . READ ALOUD RAMONA , Reading aloud is a classic parent-child activity, particularly before the child can read on his or her own. There are many benefits to continuing this practice, even after a child is an established reader. When elementary school teachers read to students, they enhance students' understanding and their desire to read independently. (Ivey, 2003) Children who first hear a book read aloud often want to read it again for themselves. And what could be better after reading a great book than discovering it has a sequel – or, in the case of Ramona, seven sequels? Having an adult available to explain difficult words and concepts takes much of the frustration out of reading for younger children. (Ivey, 2003) Kids reading Ramona the Pest may be just as puzzled as Ramona when her teacher explains that “present” means not only a gift, but a period of time: “Present should mean a present, just as attack should mean to stick tacks into people.” This is a good introduction for a discussion about dual meanings of words, which are often confusing for children of Ramona’s age, as well as older children who struggle with reading. Ramona herself is an eager reader, and thrilled with the power she develops over words throughout the series. Her enthusiasm is contagious – Ramona makes books sound like fun, and kids want to experience that fun for themselves. Finally, today’s parents and teachers have likely grown up reading the Ramona books themselves. Reading aloud is an opportunity to pass on these beloved stories to their children and students, and introduce a new generation to the wonderful world of Ramona. As an added bonus, reading the books aloud lets adults revisit Ramona’s world for themselves, again and again. And isn’t that the best reason of all? NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children REFERENCES . , Benson, L. (1999). The hidden curriculum and the child's new discourse: Beverly Cleary's Ramona goes to school. Children's Literature in Education 30 (1), pp 9-29 "Beverly Cleary", in Contemporary Authors Online. (A profile of the author's life and works). Retrieved from http://infotrac.galegroup.com.proxy.libraries.rutgers.edu/itw/infomark/107/721/7826980w16/p url=rc1_CA_0_H1000018612&dyn=3!xrn_1_0_H1000018612?sw_aep=new67449 Chatton, B. (1995). Ramona and her neighbors: Why we love them. Horn Book Magazine,71 (3), p297 Cleary, B. (1955). Beezus and Ramona. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1968). Ramona the Pest. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1975). Ramona the Brave. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1977). Ramona and Her Father. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1979). Ramona and Her Mother. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1981). Ramona Quimby, Age 8. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1984). Ramona Forever. Morrow. Cleary, B. (1999). Ramona’s World. Morrow. NEWS 17:610:547:90 Materials for Children . Cleary, B. (1988). A Girl From Yamhill. Harper Collins. Cleary, B. (1995). My Own Two Feet. Avon Camelot. , Harper Collins. The world of Ramona: A teaching guide for Beverly Cleary’s Ramona books. Retrieved from http://www.walden.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/RamonasWorld_TG_31.pdf Ivey, G. (2003). 'The teacher makes it more explainable' and other reasons to read aloud in the intermediate grades. Reading Teacher, 56(8), p812. 3p Paul, P. (2011). The ageless appeal of Beverly Cleary. The New York Times. Schwarz, B. (2011). My Ramona: Beverly Cleary’s body of work shows why topicality derails great literature. The Atlantic, 125-127. Shaw, Christen, (2013). Beverly Cleary. SPECTRUM Home & School Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.incwell.com/Biographies/Cleary,Beverly.html Smith, B. (2006). Third Floor Publishing - Literature Study - Beverly Cleary's Childhood Memories Make Great Children's Stories. Retrieved from http://www.chfweb.com/smith/bcleary.html Staino, R. (2010). Beverly Cleary Turns 94. School Library Journal, 56(4). Vanderkam, L. (2010, July 30). Ramona and the Middle-Class Squeeze. Wall Street Journal - Eastern Edition. p. W9.