Improving Social Skills by Building Fluency on Deictic Framing and

advertisement

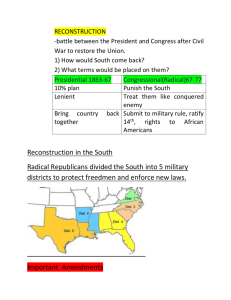

Improving Social Skills by Building Fluency on Deictic Relational Classes Donny Newsome, MA University of Nevada, Reno The Challenge of Teaching Social Skills • • • • • • Slippery – difficult to define Subtle Contextually dependent Subjective Impacts Quality of Life Collateral problem behaviors – Verbal abuse – Theft – Property destruction Traditional Approaches • Component Skills Deficit Model - Views knowledge of rules as being key component skills of the broader social repertoire • “eye contact is good, but not for too long” • “don’t stare” • “do unto others….” • “always say please and thank you” The Problems with Rule-Based Approaches • Infinite number of rules • Limited applicability of a single rule – ‘always say please and thank you…..well, not always….just most of the time….well, really just when it is socially appropriate to do so…but not at times when it isn’t…..’ • Rigidity – Lack of contextual sensitivity • Insensitivity to changes in contingencies not described in the rule – (Haas & Hayes, 2006; Hayes, Brownstein, Haas, & Greenway, 1986; Hayes, Strosal & Wilson, 1999; Skinner, 1957) Alternative: Experiential Contact • Non-specific feedback on performance, but not rules – (Azrin & Hayes, 1984; Rosenfarb, Hayes & Linehan, 1989) • Outperformed rule-based strategies *Requires a certain minimal repertoire to be sensitive to feedback and subtle differences in social contingencies New Conceptualization of Component Skills Deficit Model • Emerging approaches: Component skills identified at a more fundamental level of cognitive processes – Similar to Johnson & Layng (1992) definition of tool skills: “the most basic elements of more complex skills” (pg 1479). New Conceptualization of Skill Deficit Model • Deficits are at the level of basic verbal processes (relational responding), not in knowledge of rules • Basic relational operants are not situationspecific • Allows for a generative approach to social skill acquisition • Promotes meaningful contact and sensitivity to subtle social cues and contingencies – Making room for shaping to occur RFT – Perspective Taking • Deictic Frames – 3 Types of relations I – you Here – there Now – then – 3 Levels of Complexity Simple Reversed Double-reversed RFT – Perspective Taking • Validity in Evidence: – Performance on ToM tasks in social anhedonia and schizophrenia (Barnes-Holmes, et al. 2004; Villatte, et al. 2008; Villatte, et al. 2010; Weil, et al. 2010) – Deficits in perspective-taking tasks in ASD relative to controls (Rehfeldt, et al 2007) – IQ (RFT–PT) (Gore, et al. 2010) Case Study - Background • 24 yr old Male, JP • Autism, Mild MR, ADHD, Speech impediment (stutter) • Problem Behaviors: – – – – Verbal abuse Stealing Property destruction Refusals • Acquisition Targets: – Appropriate conversation skills – Coping skills – Compromising Case Study – Initial Protocol • Began with standard differential reinforcement protocol combined with replacement behavior training (RBT) • RBT protocols included role-playing with feedback and hypothetical-situation exercises • Some acquisition targets moved, but problem behaviors also increased Case Study – Revised Protocol • Included fluency training on simple deictic relations – Daily training on I – You relations – Weekly probes for Here – There and Now – Then relations • Additional fluency programs for socially relevant skills – – – – – – – F/S Emotion terms H/S Complete sentence with emotive term H/S Emotion for event F/S Positive statements H/S What you can do to help F/S Thoughts about standing in line F/S Thoughts about life in 10 years Baseline Differential Reinforcement + RBT Differential Reinforcement + RBT + Deictic Replacement Behaviors Problem Behaviors 300 Replacement Bx 250 Baseline Differential Reinforcement + RBT 200 Differential Reinforcement + RBT + Deictic Appr.Conversation 150 Compromising Coping Skills 100 50 0 May June July September October November December January February Problem Bx 100 80 August Differential Reinforcement + RBT Baseline Differential Reinforcement + RBT + Deictic 60 Stealing Physical Aggression Verbal Abuse 40 Refusals 20 0 May June July August September October November December January February Case Study - Results • Targeting deictic relational skills appeared to improve sensitivity to programmed social contingencies • This was accomplished by only training simple relations • Also found that training all 3 deictic relations was not necessary I - You Here – There & Now - Then Incorrect Responses Case Study – Caveats & Questions • Idiosyncratic? • ‘True’ fluency was difficult to measure due to stuttering issue • Unable to say which programs were critical to success • Incremental utility of training reversed and double-reversed relations Case Study - Contributions • Practical Utility • Value of a fluency-based approach and SCC measurement system • Utility of time-series analysis References • • • • • • • Azrin, R.D., Hayes, S.C. (1984). The Discrimination of Interest Within a Heterosexual Interaction: Training, Generalization, and Effects of Social Skills. Behavior Therapy, 15, 173-184. Gore, J.N., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Murphy, G. (2010). The relationship between intellectual functioning and relational perspective-taking. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10-1, 1-17. Barnes-Holmes Y., McHugh, L., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2004). Perspective-taking and theory of mind: A relational frame account. The Behavior Analyst Today, 5, 15-25. Haas, J. R., Hayes, S. C. (2006). When knowing you are doing well hinders performance: Exploring the interaction between rules and feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26 (1,2), pp. 91-111. Hayes, S.C., Brownstein, A.J., Haas, J.R. & Greenway, D.E. (1986). Instructions, multiple schedules, and extinction: Distinguishing rule-governed from schedulecontrolled behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 46(2): 137-147. Hayes, S.C, Strosal, K.D., Wilson, K.G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. The Guilford Press, New York, NY. Johnson, K.R., Layng, T.V. (1992). Breaking the structuralist barrier, literacy and numeracy with fluency. American Psychologist, 47(11), 1475-1490. References • • • • • • • McHugh, L., Barnes-Holmes, Y. & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2004). Perspective-taking as relational responding: A developmental profile. The Psychological Record, 54, 115-144. Rehfeldt, R.A., Dillen, J.E., Ziomek, M.M. & Kowalchuk, R.K. (2007). Assessing relational learning deficits in perspective-taking with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. The Psychological Record, 57, 23-47. Rosenfarb, I.S., Hayes, S.C., Linehan, M.M. (1989). Instructions and experiential feedback in the treatment of social skills deficits in adults. Psychotherapy, 26(2), 242-251. Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior. Copley Publishing Group. Acton, Massachusetts. Villatte, M., Monestes, J., McHuch, L., Baque, E.F., Loas, G. (2008). Assessing deictic relational responding in social anhedonia: A functional approach to the development of theory of mind impairments. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 4-4, 360-373. Villatte, M., Monestes, J., McHuch, L., Baque, E.F., Loas, G. (2010). Adopting the perspective of another in belief attribution: The contribution of relational frame theory to the understanding of impairments in schizophrenia. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 41, 125-134. Weil, T. M. & Hayes, S. C. (Under Review) Impact of training deictic frames on Theory of Mind in Children. Psychological Record.