Picture - Liz Redford

advertisement

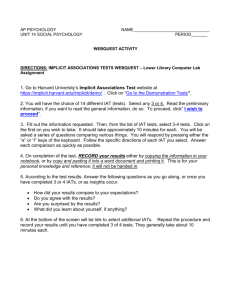

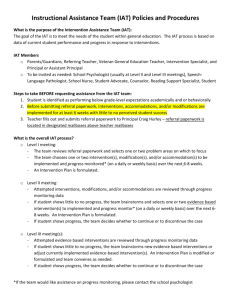

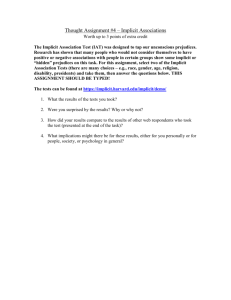

Implicit Preference for White People over Black People Decreases with Repeated Implicit Association Tests (IATs) Emma Grisham, Dylan Musselman, Taylor Barnette, Melissa Powers, Gorana Gonzalez, John Conway, Rick Klein, Liz Redford University of Florida Discussion Introduction The purpose of this study is to investigate whether familiarity with Implicit Attitude Tests (IATs) poses a threat to the methodological validity of the measure and reliability of the data. It is important to continuously analyze the validity of a measure to recognize and understand its limitations. We hypothesize that implicit biases decrease with experience taking implicit attitude measures. Since it’s invention, several concerns have arisen regarding the methodological validity of the IAT and practice effects, or effects on performance due to repeated exposure to a task. Nosek, Banaji, and Greenwald (2002) rationalized that individuals who participant in multiple IATs have little to no significant effect on observed results. Even so, research is geared towards improving the IAT, specifically the inclusion of practice trials. Research by Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003) has shown that inclusion of practice trials results in a better interpretation of implicit attitudes. However, these same findings show evidence that with practice, implicit biases decrease, both within the session and with past IAT experience. A current investigation was a 2011 study showing that participants can be taught to practice strategies to fake IAT scores (Rohner, Schroder-Abe, & Schutz). Are practice effects a more serious issue? Methods We used data from a 2013 sample from the demonstration website of Project Implicit, a website where volunteers can choose from a variety of tests to measure their unintended biases (implicit.harvard.edu). See Figure 1 and Figure 2. Participants in this study completed the Race (Black faces vs. White faces) Implicit Association Test (IAT). In addition to the standard 5 trial IAT, participants were asked sets of explicit measures on racial attitude, sets of personality and political opinion questions, and demographic questions. Participants were mostly female (61.5%) and White (69.7%). 12.5% were Black or African American, and the remaining (17.8%) were Native American/Alaskan, East or South Asian, Pacific Islander, Multiracial, or other. Participants took the IAT and were then given their IAT score. Examples of the Race Implicit Association Test. The IAT uses reaction times to measure implicit attitudes. Figure 1. A picture of the race IAT, matching “Black People” with “Bad” Figure 2. A picture of the race IAT, matching “White People” with “Good” Results Figure 3. Results from the Race Implicit Association Test. A significant difference was present in all except for the last two conditions (taking the IAT 3-5 times or 6+ times previously). We used an ANOVA to analyze mean differences in IAT scores between five groups based on the number of IATs participants had previously taken: 0, 1, 2, 3-5, 6+. Levene’s test was significant, (4, 119022) = 3.34, p = 0.01, so we report Welch’s F. The omnibus test of mean differences was significant, F (4, 6195.90)= 151.30, p < .0001. Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons revealed that, as previous experience with IATs increased, IAT D score decreased. Each increase in IAT experience was associated with a significant decrease in IAT score (all ps < .04; see Figure 3) except between the two most experienced groups (p = .40). The greatest difference was observed between those with no prior experience, M = .34, SD = .45, and those with the most, M = .21, SD = .44, d = .30, a medium effect size. Our purpose was to test the hypothesis that people who take the IAT more would have lower mean IAT scores. Our hypothesis was supported, and the overall effect size was very large. Practice effects may explain this result. There is a chance that people learn how to respond faster, thus reducing their measured bias each time they take the IAT. They then appear to have less bias than they really do; in other words, they beat the system. Alternatively, it could be that people are motivated to become less prejudiced the more that they take the IAT. This presents us with a third variable problem: people who are motivated to reduce their prejudice may be the people who are more likely to take the IAT repeatedly to assess their progress. If the score decrease is due to practice effects, as we are proposing, then the IAT may be less valid after multiple uses. Our main limitation is that we cannot make causal conclusions because our data is correlational. Future studies should test whether the same results obtain with IATs measuring attitudes toward social categories other than race, such as gender or sexual orientation. References Greenwald, A. G, Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 197-216. Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration website. Group Dynamics, 6, 101-115. Rohner, J., Schroder-Abe, M., Schutz, A. (2011). Exaggeration is harder than understatement, but practice makes perfect!: Faking success in the IAT. Experimental Psychology, 58, 464-472.