I = 250 - Cass Business School

advertisement

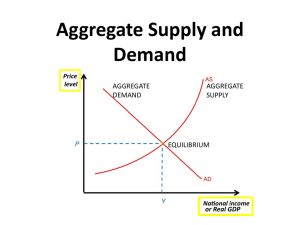

Introduction to Macroeconomics MSc Induction Simon Hayley Simon.Hayley.1@city.ac.uk What is Macroeconomics? • Macroeconomics looks at the economy as a whole. It studies aggregate effects, such as: • Business cycles • Living standards (real incomes) • Inflation • Unemployment • The balance of payments. • It also asks how governments can use their monetary and fiscal policy instruments to help stabilise the economy. Key Issues • Why analyse macroeconomics? • Measuring economic activity • Building a macroeconomic model • Macroeconomic problems and policy solutions Real GDP at 1985 prices, United Kingdom 1885-2005, £ billion 700 600 billions 1985 £s 500 400 300 200 100 0 1885 1895 1905 1915 1925 1935 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 Real GDP growth rate, United Kingdom 1886-2005 20 Annual rate of change per cent 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 1886 1896 1906 1916 1926 1936 1946 -15 Year 1956 1966 1976 1986 1996 UK GDP Gap, 1970-2006 8 4 2 0 -2 -4 20 00 19 85 -6 19 70 percent of Y* 6 Year UK Claimant Count Unemployment, 1885-2005 20 18 Per cent of workforce 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1885 1895 1905 1915 1925 1935 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005 UK Inflation (% per annum) 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1961 1965 1969 1973 1977 1981 1985 1989 1993 1997 2001 2005 2009 How Can We Measure National Output? • Key concepts: – Gross domestic product (GDP) – Gross national income (GNI - used to be called GNP) – in a closed economy GDP = GNI • Aggregate supply and demand: – Controlling inflation and unemployment – Fiscal and monetary policy Avoiding Double Counting • To avoid double counting, when measuring national output via spending on goods, the goods that count as part of the economy’s output are called final goods; all others are called intermediate goods. • Each firm’s contribution to total output is equal to its value added: the gross value of the firm’s output minus the value of all intermediate goods and services (the outputs of other firms) that it uses. • The sum of all the values added produced in an economy is called gross value added at basic prices (the prices received by producers net of taxes on products, plus subsidies). Three Routes to GDP • All output is owned by someone, and all output is bought by someone. Thus gross domestic product, [GDP] can be calculated in three different ways: 1) As the sum of value added by all producers of both intermediate and final goods 2) As the income claims generated by the total production of goods and services 3) As the expenditure needed to purchase all final goods and services produced during the period. • These three methods reach the same total, so long as we add taxes on products [minus subsidies] to the first two in order to measure GDP at market prices. The Circular Flow of Income, Output, and Expenditure Domestic households Financial System Abroad Government Domestic producers An Example • Suppose an economy has two firms: – Firm A mines ore; it sell £300 worth to firm B, pays £200 to its workers, and makes £100 profit. – Firm B makes consumer goods; it buys materials for £300 from firm A, pays £300 to its workers, sells it output for £800 and makes profit of £200. • What is GDP? • Value of final goods sold = £800 • Value added of two firms: Firm A = £300, Firm B = £500 so total = £800 • Sum of incomes: Wages = £200 + £300; profits = £100 + £200 so total = £800 Types of Final Expenditure From the expenditure side of the national accounts: • GDP = C + I + G + [X - M]. • C is private consumption expenditures. • I is investment in fixed capital [including residential construction], inventories, and valuables. • G is government consumption. • (X -M) represents net exports, or exports minus imports; it will be negative if imports exceed exports.…also referred to as NX Gross value added at current basic prices, by sector, UK, 2005 £ million % of GDP Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fisheries 10,241 0.8 Mining and quarrying 25,458 2.1 148,097 12.2 Electricity, gas and water supply 24,953 2.0 Construction 65,923 5.4 132,113 10.8 Hotels and restaurants 33,730 2.8 Transport and communications 81,059 6.6 266,485 21.8 Public administration and defence 54,935 4.5 Education 62,316 5.1 Health and social work 81,518 6.7 Other services 58,807 4.8 Sector Manufacturing Wholesale and retail trade Financial intermediation and real estate Gross value added at current basic prices Plus adjustment to current basic prices (taxes minus subsidies on products) = GDP at market prices 1,086,859 137,856 11.3 1,224,715 100 Expenditure-based GDP and its components, UK, 2005 Expenditure Categories Individual consumption Household final consumption £ million % of GDP 760,777 62 30,525 2.5 Individual government final consumption 165,655 13.5 Total actual individual consumption 956,957 78.1 Collective government final consumption 101,875 8.3 Total final consumption 1,058,832 86.5 Gross fixed capital formation 205,843 16.8 3,721 0.3 -337 0 209,187 17.1 322,298 26.3 Less imports of goods and services -366,540 -29.9 External balance of goods and services (net exports) -44,242 -3.6 Final consumption of non-profit institutions serving households Change in inventories Acquisition less disposals of valuables Total gross capital formation Exports of goods and services Statistical discrepancy Gross domestic product at market prices (money GDP) 938 1,224,715 100 GDP and GNI by Income type 2005 Income type £ million % of GDP 312,026 25.5 76,112 6.2 Compensation of employees 684,618 55.9 Taxes on production and imports 162,267 13.2 -9,391 -0.8 -917 0.0 1,224,715 100 Operating surplus, gross (profits) Mixed incomes Less subsidies Statistical discrepancy GDP at market prices Employees’ compensation Receipts from rest of world 1,211 Less payment to rest of world Total -1,137 74 Less taxes on production paid to rest of world Plus subsidies received from rest of world -4,243 Other subsidies on production Property and entrepreneurial income Receipts from rest of world Less payments to rest of world Total Gross national income (GNI) at market prices 3,216 185,826 -156,029 29,797 1,253,561 • Real GDP is calculated to reflect changes in real volumes of output and real income. Nominal GDP reflects changes in both prices and quantities. • Thus growth in nominal GDP can be split into real GDP growth plus inflation. • Gross means that no allowance has been made for depreciation. • Personal disposable income is the amount actually available for individuals to spend or to save (after taxes). Building a Macro Model • Assumptions used in building a macro model • Key relationships: – consumption – investment • The determination of GDP • The multiplier • The “big idea”: the Keynesian revolution Key Assumptions • Economy assumed to be one big industry • Final spending is demand for output of this one industry • Government purchases, consumption, investment and exports are all demands for the same output. Labour Output of goods Consumer spending Investment Government purchases Exportsimports More Assumptions • Temporary assumptions: – Prices don’t change, so all changes are in real (volume) terms – There is excess capacity in production so output is demand determined – Closed economy with no government • Focus first on: – GDP = C + I [+ G + (X-M)] – Use symbol Y for GDP – So first explain GDP using determinants of C and I. – C is an endogenous variable determined within the model – I is an exogenous variable determined outside the model The Circular Flow of Income, Output, and Expenditure Domestic households Financial System Abroad Government Domestic producers Consumption and Saving • If personal disposable income rises, households spend some of the increase and save the rest. This is measured by the marginal propensity to consume [MPC] and the marginal propensity to save [MPS], which are both positive and sum to one. • Relation between consumption and income might be: – C = a + bY – “a” is referred to as “autonomous consumption”. It is the amount that consumers spend when income is zero. – “b” is the marginal propensity to consume. – This implies a relation for saving: – S = -a + (1-b)Y Consumer spending and personal disposable income, UK, quarterly, 1955-2005 (£M at constant 2002 prices) 250000 £ million at 2002 prices 200000 Disposable income 150000 100000 Consumer spending 50000 0 1955 Q1 1960 Q1 1965 Q1 1970 Q1 1975 Q1 1980 Q1 1985 Q1 1990 Q1 1995 Q1 2000 Q1 2005 Q1 Consumption and Saving Relationships: empirical example • C = 100 + 0.8Y – where C is consumer spending in a period, Y is personal disposable income (which in absence of taxes and retained profit = GDP). Autonomous C = 100; Marginal propensity to consume = 0.8. • S = -100 + 0.2Y – Marginal propensity to save = 0.2 Consumption and Saving Schedules [£ Million] Disposable Income 0 100 400 500 1000 1500 1750 2000 3000 4000 Desired consumption 100 180 420 500 900 1300 1500 1700 2500 3300 Desired saving -100 -80 -20 0 +100 +200 +250 +300 +500 +700 The Consumption and Saving Functions 450 2000 C 1500 500 S 1000 250 500 0 -100 450 500 -500 1000 1500 2000 Real Disposable Income (i). Consumption Function[£ million] 500 1000 1500 2000 Real Disposable Income (ii). Saving Function[£ million] Investment • Here we treat investment as an exogenous variable, that is, it is determined outside the model. • Later we can make investment depend on the interest rate. • In general investment will depend on expectations of future demand growth as well as interest rates. • For our numerical example investment is constant at 250. The Aggregate Expenditure Function in a Closed Economy With No Government [£ Million] GDP [National Income] [Y] 100 400 500 1000 1500 1750 2000 3000 4000 Desired consumption expenditure [C = 100 +0.8Y] Desired investment expenditure [I = 250] 180 420 500 900 1300 1500 1700 2500 3300 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 Desired aggregate expenditure [AE = C + I] 430 670 750 1150 1550 1750 1950 2750 3550 Equilibrium GDP • At the equilibrium level of GDP, purchasers wish to buy exactly the amount of national output that is being produced. – At GDP above equilibrium, desired expenditure falls short of national output, and output will sooner or later be curtailed. – At GDP below equilibrium, desired expenditure exceeds national output, and output will sooner or later be increased. • In a closed economy with no government, desired saving equals desired investment at equilibrium GDP. • Equilibrium GDP is represented graphically by the point at which the aggregate expenditure curve cuts the 450 line, that is, where total desired expenditure equals total output. • This is the same level of GDP at which the saving function intersects the investment function. The Determination of Equilibrium GDP GDP [National Income] [Y] 100 400 500 1000 1500 1750 2000 3000 4000 Desired aggregate expenditure [AE = C + I] 430 670 750 1150 1550 1750 1950 2750 3550 Shortage of goods. Pressure on Y to rise Equilibrium Y Surplus production. Pressure on Y to fall Equilibrium GDP 450 [AE = Y] 3000 E0 Desired saving (£m) 2000 1000 350 0 S 500 450 I 250 0 -100 -500 1000 Y0 2000 3000 Real National Income [GDP] [£m] 1000 Y0 2000 3000 Real National Income [GDP] [£m] [i]. An Aggregate Expenditure Function[AE = Y] [ii]. Saving Function[S = I] How Does the Equilibrium Come About? • For GDP to remain unchanged injections of spending and leakages must be just equal; otherwise GDP would be changing • Imagine a bath with the tap running and no plug. For the water level to be stable the water flowing in and the water flowing out must be the same. The Model “Solution” • The model is: Y=C+I C = a + bY • Solve for Y by substituting for C in first equation Y = a + bY + I so: Y - bY = a + I or Y = (a + I)/(1-b) • Numerical example: C = 100 + 0.8Y & I = 250 So Y = 100 + 0.8Y + 250 Or Y = (100 + 250)/ (1- 0.8) = 350 x 5 = 1750 Changes in GDP • Equilibrium GDP is increased by a rise in exogenous spending or “injections” or a fall in “withdrawals”. • Equilibrium GDP is decreased by a fall in injections or a rise in withdrawals. • The magnitude of the effect on GDP of shifts in autonomous expenditure is given by the multiplier. It is defined as K = Y/A, where A is the change in “autonomous” or “exogenous” expenditure. • It is equal to 1/(1 - z), where z is the marginal propensity to consume. Thus the larger z is, the larger is the multiplier. In the absence of taxes and foreign trade the multiplier is: • 1/(1-b) where “b” is the marginal propensity to consume • If b = 0.8 then the multiplier = 5. The Simple Multiplier AE = Y AE0 e0 E 0 450 0 Y0 Real National Income [GDP] The Simple Multiplier AE = Y AE1 E1 e1 a e’1 AE0 A e0 E0 Y 450 0 Y0 Y1 Real National Income [GDP] New solution when I rises from 250 to 350 • • • • • • Old level of GDP was 1750 Y=C+I Y = 100 + 0.8Y + 350 Y - 0.8Y = 450 Y = 450 x 5 Y = 2250 • • • • Increase in Y is change in I times the multiplier Change in I is £100 and multiplier is 5 So change in Y is £500. At new level of GDP: S= -100 + (.2 x 2250) = 350 The Multiplier: Intuition • If there is an increase of exogenous spending of £100, this generates £100 of extra income and £80 gets spent. • The £80 generates extra income of £80 and 0.8 of this gets spent---creating £64 of extra income. 0.8 of this gets spent generating £51.20 of extra income. • Total income generated is: £100 + £80 + £64 + £51.2 + £40.96 + £32.768 + £26.21 + £20.97 +£16.78 + £13.43 + £10.74 + £8.59 + £6.87 + £5.5 + £4.4 + £3.52 + £2.82 + £2.25 + £1.8 + £1.44 + £1.15 + £0.92 + £0.74 + £0.59 + £0.47 + £0.38 + £0.3 + £0.24 + £0.19 + £0.15 + £0.12 + £0.1 + £0.08 + £0.064 This sum converges to £500. The Multiplier: a Numerical Example 500 400 300 200 100 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Spending round 15 20 Implications of the Multiplier • The multiplier comes about because consumer spending is a function of household incomes, but household incomes are themselves affected by consumer spending! (the circular flow of income) • The result is that a small change in one part of our model (eg. I, G, or the MPC) can have a large impact on GDP by the time the economy has reached a new equilibrium. The “Classical” View of Unemployment • Economists used to regard the labour market as just like any other market. If there was an excess supply of labour, this must mean that the “price” (wages) is too high. • But this theory left economists unable to come up with a satisfactory explanation of the great depression... • ...let alone come up with any solutions! The Classical View of Unemployment S D Z Z Y Y X X W W V V U U Employment The “Big Idea”: Keynesian Revolution • Unemployment is mainly determined by aggregate spending. Thus the economy can get stuck in a vicious circle (low aggregate spending => low GDP => high unemployment => low aggregate spending). • Cutting wages would make matters worse by further reducing consumer demand! • One “solution” is for government to use its own spending (and tax changes) to boost demand. The budget then became a tool for managing the economy (discretionary fiscal policy). The Circular Flow of Income, Output, and Expenditure Domestic households Financial System Abroad Government Domestic producers The Keynesian Revolution AE = Y AE0 e0 E0 450 0 Y0 Y* Real National Income [GDP] Effect on GDP of change in exogenous spending AE = Y AE1 E1 e1 a e’1 AE0 A e0 E0 Y 450 0 Y0 Y1 Real National Income [GDP] Aggregate Demand and Supply • So far we have assumed that GDP is determined by demand. This is the case if there is excess capacity in the economy (no supply-side constraints). • Our model also has no role for prices, so it cannot explain inflation. So next we incorporate the price level and derive the aggregate demand curve. • We then add the aggregate supply curve, which enables us to determine both real GDP and the price level. Aggregate Demand What happens to AE as we change the price level? – A fall in the price level shifts the AE curve upwards – A rise in the price level shifts the AE curve downwards. The reasons: – A rise in the price level lowers exports because it raises the relative price of domestic goods – A rise in the price level lowers private consumption spending because it decreases the real value of consumers’ wealth. – Both of these changes lower equilibrium GDP and cause the aggregate demand curve to have a negative slope. • The AD curve plots the equilibrium level of GDP that corresponds to each possible price level. A change in equilibrium GDP following a change in the price level is shown by a movement along the AD curve. The AD Curve and the AE Curve AE0 AE = Y Desired Expenditure E0 AE1 E1 AE2 E2 45o 0 Y2 Y1 Y0 Real National Income [GDP] [i]. Aggregate expenditure E2 P2 E1 P 1 E0 P 0 AD 0 Y2 Y1 Y0 [ii]. Aggregate Demand Real National Income (GDP) AD Meaning and Shifts • The AD curve is drawn for given values of all exogenous expenditures and other parameters • Each point on AD shows, for each P, the level of real GDP that is consistent with: – desired spending = actual output (as determined by spending decisions) – injections = withdrawals • When an exogenous variable changes, the AD curve shifts at each price level by the shift in spending times the multiplier. Shifts in Aggregate Demand • The AD curve shifts when any element of exogenous expenditure changes. • The multiplier times the shift in exogenous spending measures the magnitude of the shift. • An increase in a, G, I, X, or a fall in T shift AD to the right. • A fall in a, G, I, X, or a rise in T shift AD to the left. The Simple Multiplier and Shifts in the AD Curve AE = Y AE1 Desired Expenditure E1 AE0 E0 A 45o [i]. Aggregate Expenditure 0 Y0 Real GDP Y1 E0 E1 P0 Y AD0 [ii]. Aggregate Demand 0 Y0 Y1 AD1 Real GDP Aggregate Supply • The short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve is drawn for given input prices, given technology and fixed capital stock. • It is positively sloped because unit costs rise with increasing output and because rising product prices make it profitable to increase output. • An increase in productivity or a decrease in input prices shifts the SRAS curve to the right. • A decrease in productivity or an increase in input prices shifts the SRAS curve to the left. A Short-run Aggregate Supply Curve SRAS Price level P1 P 0 Y0 Y1 Real GDP Macroeconomic Equilibrium • Macroeconomic equilibrium is where the AD and SRAS curves intersect. • Shifts in the AD and SRAS curves, called aggregate demand shocks and aggregate supply shocks, change the equilibrium values of real GDP and the price level. • When the SRAS curve is positively sloped, an aggregate demand shock causes the price level and real GDP to move in the same direction, the division between these effects depending on the shape of the SRAS curve. • The main effect is on real GDP when the SRAS curve is flat and on the price level when it is steep. Macroeconomic Equilibrium AD SRAS E0 P0 0 Y0 Real GDP Supply Shocks • An aggregate supply shock moves equilibrium real GDP along the AD curve, causing the price level and output to move in opposite directions. • A leftward shift in the SRAS curve causes stagflation: rising prices and falling output. • A rightward shift causes an increase in real GDP and a fall in the price level. • The division of the effects of a shift in SRAS between a change in real GDP and a change in the price level depends on the shape of the AD curve. Aggregate Supply Shift AD SRAS E0 P0 P 1 0 Y0 Y 1 Real GDP Starting from AD = SRAS there can be two types of shock: • Aggregate demand shock involves a change in some exogenous spending category: a, I, G (or T) and X. – An increase in a, I, G, or X shifts AD left or right by size of change times the multiplier. – Price level then changes and makes multiplier smaller, but P and Y respond to AD shock in same direction. • When there is an aggregate supply shock, P and Y move in opposite directions. • There are some special cases. Keynesian SRAS Curve AD E0 SRAS P0 0 Y0 Real GDP Classical or Monetarist SRAS AD SRAS P0 0 Y0 Real GDP General Case AD SRAS P0 0 Y0 Real GDP Lessons of the 1970s and 1980s Inflation is persistent – Expected inflation rises, so workers demand higher wage increases (wage-price spiral). – If inflation is high, employees demand high wage rises. Firms then raise prices to maintain margins. – Inflation expectations are important. Unemployment is persistent – The long-term unemployed become less attractive to employers. – Hence wage inflation tends to increase even when unemployment relatively high. What About The Money Supply? • Monetarists argued that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, so if you can control the money supply, you can control inflation. • But although money is involved in every transaction, it is seldom the cause of the transaction. The relationship between money and inflation is not stable, so it is not a reliable means of controlling inflation. • Furthermore, in a modern economy, the money supply (largely in the form of bank accounts) is hard to control, or even measure. Evolution of macro-economic policymaking • Classical (1776 - 1930s) – Free markets with no government interference • Keynesian (1930s – 1970s) – Discretionary demand management used to regulate economy • Monetarist (1970s – 1980s) – Control money supply to control inflation – Supply-side measures to help markets move to equilibrium – Markets should then clear to achieve full employment – Instead the economy entered deep recession in early 1980s. Monetarist theory discredited. • Current pragmatic system – Inflation expectations are important, so objectives must be clear and credible – Independent central bank avoids political motives Stabilisation Policies • Fiscal policy – Budget deficit boosts demand – But cyclical adjustment is needed to be sure – Substantial lags: obtaining data, implementation and impact of policy shift. Hence net effect could be destabilising. • Monetary policy – Interest rates affect investment and consumer spending • Governments now generally set fiscal policy and leave the central bank to use monetary policy to stabilise the economy. Macroeconomics: summary Measuring GDP: – Value added – Income – Expenditure Circular flow of income – Keynesianism overthrows classical view of unemployment Model building: – Multiplier – Supply and demand shocks – Different view of aggregate supply Macroeconomic policy: – – – – Classical Keynesianism Monetarism Pragmatic view. Independent central banks Reading Lipsey + Chrystal “Economics” Eleventh Edition, Oxford University Press, 2007. This is the source of most of the material presented in these lectures.