The 2011 Summer Reading Program

advertisement

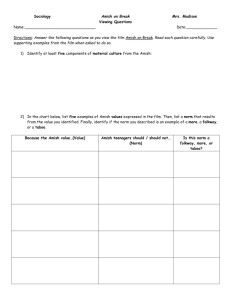

Bishop McGuinness Catholic High School The 2011 Summer Reading Program Social Justice: The Role of Media Bishop McGuinness Catholic High School is committed to modeling excellence so that we may serve in a world in need of peace, love, and justice. Bishop McGuinness values the transformational growth that takes place when teachers and students experience the joy of learning together. A collaborative academic culture nurtures intellectual courage, curiosity, and creativity. Bishop McGuinness values relationships that connect members of the school community to each other and to the larger world. BMHS aspires to be a nurturing community that respects the dignity of every human being. Bishop McGuinness is an academically talented and diverse community that prepares students for college and active citizenship in a global society. Consistent with Bishop McGuinness Catholic High School’s mission and values, the summer reading program for the 2011-2012 school year is designed to investigate elements of social justice and focuses on issues of media from a global perspective. For this year’s reading, students have a list of books from which to choose one. During the opening week of school, students and teachers will begin discussing the books they have read as well as the ways in which the media affect each of us daily. Since our global society is not compartmentalized, as active citizens we must be prepared to engage important issues and ideas with people from diverse cultures. To that end, discussion groups will combine students across grade levels and faculty across disciplines in ways that will allow all of us to grow together as individuals and as a community. Students in Honors and AP courses at the junior and senior level will be required to complete this project as well as additional summer reading. Please check the Bishop McGuinness website (www.bmhs.us) for additional information concerning these assignments. Students may sign up for their chosen book beginning April 18 in the Cafeteria during their lunch periods. Each student should sign up for one book only. No more than 40 students may sign up for any one book in order to allow new students their choices as well. Incoming freshmen will sign up for their book choice when they register for classes. All students are required to complete their summer reading assignment on the book for which they originally signed up. The summer reading assignment is explained on page 5. Please sign up for ONE of the following ten 2011 Summer Reading titles: *** Portions of the above attributed to St. Mary’s Episcopal School, Raleigh, NC *** 1 Parents, please help your student select a book appropriate for him or her. Your involvement assures us that the book’s theme and content are age appropriate and respect the family’s values and interests. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot Henrietta Lacks was a mother of five in Baltimore, a poor African American migrant from the tobacco farms of Virginia, who died from a cruelly aggressive cancer at the age of 30 in 1951. A sample of her cancerous tissue, taken without her knowledge or consent, as was the custom then, turned out to provide one of the holy grails of mid-century biology: human cells that could survive--even thrive--in the lab. Known as HeLa cells, their stunning potency gave scientists a building block for countless breakthroughs, beginning with the cure for polio. Meanwhile, Henrietta's family continued to live in poverty and frequently poor health, and their discovery decades later of her unknowing contribution--and her cells' strange survival--left them full of pride, anger, and suspicion. For a decade, Skloot doggedly but compassionately gathered the threads of these stories, slowly gaining the trust of the family while helping them learn the truth about Henrietta, and with their aid she tells a rich and haunting story that asks the questions, Who owns our bodies? And who carries our memories? (Amazon.com) Amish Grace by Donald Kraybill, Steven Nolt, et al. When a gunman killed five Amish children and injured five others last in a Nickel Mines, Pa., schoolhouse, media attention rapidly turned from the tragic events to the extraordinary forgiveness demonstrated by the Amish community. The authors, who teach at small colleges with Anabaptist roots and have published books on the Amish, were contacted repeatedly by the media after the shootings to interpret this subculture. In response to the questions why—and how—did they forgive? Kraybill and his colleagues present a compelling study of Amish grace. After describing the heartbreaking attack and its aftermath, the authors establish that forgiveness is embedded in Amish society through five centuries of Anabaptist tradition, and grounded in the firm belief that forgiveness is required by the New Testament. The community's acts of forgiveness were not isolated decisions by saintly individuals but hard-won countercultural practices supported by all aspects of Amish life. This intelligent, compassionate and hopeful book is a welcome addition to the growing literature on forgiveness. (Publishers Weekly) 1984 by George Orwell The novel is set in an imaginary future world that is dominated by three perpetually warring totalitarian police states. The book's hero, Winston Smith, is a minor party functionary in one of these states. His longing for truth and decency leads him to secretly rebel against the government. Smith has a love affair with a like-minded woman, but they are both arrested by the Thought Police. The ensuing imprisonment, torture, and re-education of Smith are intended not merely to break him physically or make him submit but to root out his independent mental existence and his spiritual dignity. Orwell's warning of the dangers of totalitarianism made a deep impression on his contemporaries and upon subsequent readers, and the book's title and many of its coinages, such as NEWSPEAK, became bywords for modern political abuses. (Amazon.com) 2 Nobody Knows My Name by James Baldwin This highly personal protest Baldwin has released through a masterly use of the informal essay. Writing with both strength and delicacy, he has made the essay into a form that brings together vivid reporting, personal recollection and speculative thought. Essays in "Nobody Knows My Name" composed with equal skill: a saddening account of Baldwin's first visit South, a report on an international conference of Negro intellectuals debating whether they share a common culture, a chilling polemic against William Faulkner's views on segregation. And especially noteworthy are three essays on Richard Wright, which range in tone from disturbed affection to disturbing malice and reflect Baldwin's struggle to achieve some personal equilibrium as writer and black man by discovering his true feelings toward the older man.” (Parental Note: Contains adult themes/ language) (New York Times) The Soloist by Steve Lopez Scurrying back to his office one day, Lopez, a columnist for the L.A. Times, is stopped short by the ethereal strains of a violin. Searching for the sound, he spots a homeless man coaxing those beautiful sounds from a battered twostring violin. When the man finishes, Lopez compliments him briefly and rushes off to write about his newfound subject, Nathaniel Ayers, the homeless violinist. Over the next few days, Lopez discovers that Nathaniel was once a promising classical bass student at Juilliard, but that various pressures— including being one of a few African-American students and mounting schizophrenia—caused him to drop out. Enlisting the help of doctors, mental health professionals and professional musicians, Lopez attempts to help Nathaniel move off Skid Row, regain his dignity, develop his musical talent and free himself of the demons induced by the schizophrenia. (Publishers Weekly) (Parental Note: Contains adult themes/ language) Winter Girls by Laurie Halse Anderson Lia and Cassie had been best friends since elementary school, and each developed her own style of eating disorder that leads to disaster. Now 18, they are no longer friends. Despite their estrangement, Cassie calls Lia 33 times on the night of her death, and Lia never answers. As events play out, Lia's guilt, her need to be thin, and her fight for acceptance unravel in an almost poetic stream of consciousness in this startlingly crisp and pitch-perfect first-person narrative. All of the usual answers of specialized treatment centers, therapy, and monitoring of weight and food fail to prevail while Lia's cleverness holds sway. What happens to her in the end is much less the point than traveling with her on her agonizing journey of inexplicable pain and her attempt to make some sense of her life. (Amazon.com) 3 In Cold Blood by Truman Capote On November 15, 1959, in the small town of Holcomb, Kansas, four members of the Clutter family were savagely murdered by blasts from a shotgun. There was no apparent motive for the crime, and there were almost no clues. As Truman Capote reconstructs the murder and the investigation that led to the capture, trial, and execution of the killers, he generates both mesmerizing suspense and astonishing empathy. If all Truman Capote did was invent a new genre--journalism written with the language and structure of literature--this "nonfiction novel" about the brutal slaying of the Clutter family by two would-be robbers would be remembered as a trail-blazing experiment that has influenced countless writers. But Capote achieved more than that. He wrote a true masterpiece of creative nonfiction. (Amazon.com) (Parental Note: Contains adult themes/ language) Open: An Autobiography by Andre Agassi Agassi has always had a tortured look in his eyes on the tennis court. In 1992, when he burst onto the world sports stage by winning the Grand Slam at Wimbledon, he looked like a deer in headlights. Nobody seemed more surprised and upset by his big win that day than he did. For good reason, too. Agassi hated tennis. This is the biggest revelation in his very revealing autobiography. Agassi has hated tennis from early childhood, finding it extremely lonely out on the court. But he didn’t have a choice about playing the game because his father drove him to become a champion, like it or not. Mike Agassi, a former Golden Gloves fighter who never made it professionally, decided that his son would become a champion tennis player. In militaristic fashion, Mike pushed seven-year-old Andre to practice relentlessly until the young boy was exhausted and in pain. He also arranged for Andre, age 13, to attend a tennis camp where he was expected to pull weeds and clean toilets. The culmination of all of this parental pushing came when Andre began winning as an adult. But it didn’t make him happy. Within this framework, Agassi’s other disclosures make sense. Readers will definitely cheer when Andre finally makes peace with the game he once hated and learns to enjoy it. (Parental Note: Contains adult themes/ language) (Booklist) The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins A gripping story set in a postapocalyptic world where a replacement for the United States demands a tribute from each of its territories: two children to be used as gladiators in a televised fight to the death. Katniss, from what was once Appalachia, offers to take the place of her sister in the Hunger Games, but after this ultimate sacrifice, she is entirely focused on survival at any cost. It is her teammate, Peeta, who recognizes the importance of holding on to one's humanity in such inhuman circumstances. It's no accident that these games are presented as pop culture. Every generation projects its fear: runaway science, Communism, over-population, nuclear wars and, now, reality TV. The State of Panem—which needs to keep its tributaries subdued and its citizens complacent—may have created the Games, but mindless television is the real danger, the means by which society pacifies its citizens and punishes those who fail to conform. Will its connection to reality TV, ubiquitous today, date the book? It might, but for now, it makes this the right book at the right time. What happens if we choose entertainment over humanity? (Publishers Weekly) A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain 4 The hit on the head that sends protagonist Hank Morgan back through 13 centuries did not affect his natural resourcefulness. Using his knowledge of an upcoming eclipse, Hank escapes a death sentence, and secures an important position at court. Gradually, he introduces 19th century technology so the clever Morgan soon has an easy life. That does not stop him from making disparaging, tongue-in-cheek remarks about the inequalities and imperfections of life in Camelot. While the book pokes fun at Twain's contemporary society, the main thrust is a satire of romanticized ideas of chivalry, and of the idealization of the Middle Ages. (Amazon.com) Summer Reading 2011 Assignments You will have a variety of opportunities to discuss your summer reading book and to share your insights: 1. Two to three page typed reflection. - Type two to three pages on what you learn from the book about the relationship between social justice and the impact of media. To help you write the paper, take notes on the following questions as you read the book: a. How can media influence people? b. How can people influence media? c. What does social justice mean to you? 2. Note cards with passages to bring to your discussion groups – On note cards, write at least 4 passages from the book that relate to the main theme of the summer reading: “Social Justice: The Role of Media.” Be sure to include page numbers. 3. Discussion groups - Be prepared to participate in discussions of the book itself and the theme in general. You should use your note cards and book in the discussion, so bring both. Everyone will be expected to contribute to the discussion. All the above items will be due the first day of school. You will turn them in to your English teacher. Collectively, all three of the above items will count for a single test grade in your English class. The discussion groups will take place towards the end of the first week of school. A note about honor: Though commercially distributed summaries and outlines of some of the summer reading books are readily available, at Bishop McGuinness we expect students to read the works themselves both to get their full benefit and as a matter of honor. A Note about Summer Reading Discussion Guidelines: The objective: 5 To provide a welcoming and safe environment for all students to engage in an intellectual discussion using Socratic reasoning. Each group will have a discussion leader whose role is to keep the discussion moving; however, this leader is not so much a facilitator as he/she is an equal participant. Good discussion participants will participate in the following ways: organizing, leading summarizing, restating, clarifying offering examples from the text asking questions commenting or giving an opinion making a suggestion asking for clarification reacting to comments analyzing the text, a comment, or the discussion itself restarting the discussion filling in a hole arguing a point asking for new information asking for comments or reactions making connections with other texts, situations, or discussions A successful discussion would look like this: Everyone comes prepared with key passages and ideas highlighted for discussion. Everyone participates more or less equally. The pace allows for clarity and thoughtfulness, but not sleep. There is a sense of balance and order: focus in on one speaker and one idea at a time. There is an attempt to resolve questions and issues before moving on to new ones. There is a clear sense of what the group has covered and how. The loud do not dominate; the shy are encouraged. Everyone is clearly understood. Students are animated, sincere, and helpful. The conversation is lively. When the process is not working, the group adjusts. Those unhappy with the process say so. Students take risks and dig for new meanings. Students back up what they say with examples, quotations, etc. All students come well-prepared. The text is referred to often. 6

![An approach to answering the question about Elizabeth Bishop[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008032916_1-b08716e78f328a4fda7465a9fffa5aba-300x300.png)