Williams, T., Worley, C., Canner, N., & Lawler, E. (2012). Sustained

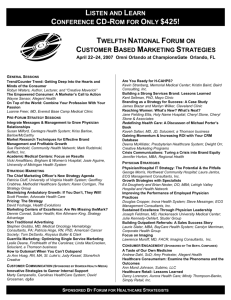

advertisement