- Society for Research into Higher Education

advertisement

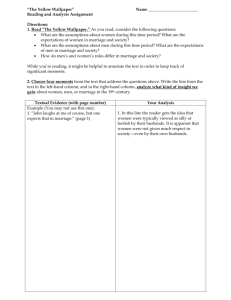

Understanding Forced Marriage Dr. Khatidja Chantler Reader, School of Social Work Email: kchantler@uclan.ac.uk Forced Marriage: An abuse of human rights • “Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 16 (2)) • “A woman’s right to choose a spouse and enter freely into marriage is central to her life and her dignity and equality as a human being.” (General Recommendation No. 21, UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women) What is Forced Marriage? • Difficult to define Forced Marriage (FM). HO definition: ‘Where one or both parties are coerced into a marriage against their will and under duress¹’ • Lack of consent (one or both parties) • Duress: includes emotional, physical, financial and other forms of violence • Positioned as distinct from arranged marriage • Is FM an issue of Honour based violence (HBV)? • Several government initiatives to prevent forced marriage ¹ http://www.communities.homeoffice.gov.uk/raceandfaith/faith/forcedmarriages Arranged Marriage • Where family introduce young people to each other based on certain criteria (e.g. language, religion, job) • Where both parties consent to marry • Romantic love may occur during courtship, but is assumed that love and commitment will develop in time • Courtship periods are quite condensed compared to Euro/American cultural practices • Growing significance of dating websites Slippery categories: Arranged or Forced Marriage Slippage between arranged and forced in some cases, especially when arranged marriage happens at the level of social expectation. I had the choice to say, erm I wasn’t forced into saying yes. But I think my mum, my parents didn’t give me enough time, or didn’t, they didn’t, even though I was about fourteen, fifteen, that’s no age to ask a girl does she want to get engaged to someone (survivor, FM, Hester et al, 2007) Forced Marriage Research in the UK 7 studies in the UK since 2006: • Gangoli et al (2006) (study based in Newcastle) • Hester et al (2007): Manchester, Birmingham, London • Brandon & Hafez (2008) • Khanum (2008): Luton • Natcen 2009: Prevalence study • MoJ (2009) – Number of FMPOs and courts using them • Freeman, M & Klein, R. (2013) College and University Responses to Forced Marriage Quantitative Data on Forced Marriage • Difficult to measure Forced Marriage: when should actions be counted as a case of FM? Before or after the marriage? • Available information is largely about South Asian communities • Kazmirski et al study (2009): 5000-8000 cases of FM in 2008 • Forced Marriage Unit also produces data (largely based on transnational marriages): • 2013: 1302; 2012: 1485; 2011: 1468 ; 2010: 1735; 2009:1682. Approximately 20% are male victims. In 2013, 33% were aged 18-21 Forced Marriage Research in the UK: Key themes • Lack of adequate recording of incidents of FM – in part because of definitional issues (Hester et al 2007) and what counts as a ‘case’ (Nat Cen 2009) • Majority of victims are young, South Asian women, but FM occurs in a range of communities (Hester et al 2007; Khanum 2008) • Differences in the conceptualisation of FM: is it purely cultural (Branden & Hafiz) or is part of gender based violence (Gangoli et al 2011) • Lack of professional knowledge and fear of intervention (Chantler, 2001, MoJ 2009) Key Interlinked Concepts ‘Race Anxiety’ Cultural Privacy Cultural Matching Culturalised thinking which positions western women as individuals but minoritsed women as cultural beings Feminist concerns becoming co-opted as part of the state apparatus in unhelpful ways Politics as shaping what can be spoken Intersections of practitioner/organisational and macro issues Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm Political Contexts and Speaking Out Batsleer et al (2002): Manchester DV helpline reported drop in Muslim women contacting the helpline post 9/11. because that [majority]community over there doesn’t know me, doesn’t want me doesn’t trust me and so, particularly if you’re from a Muslim background, it’s like you’re, it’s like your choices have suddenly over the last couple of years been diminished as a Muslim woman, diminished over time diminished with the politics and so the community feels like it’s under siege and (women) are part of that community and therefore they feel as though they are under siege and therefore they’re not going to go and take the risks and have that trusting relationship with the mainstream… (survivor of forced marriage, Hester et al 2007) Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm ‘Race Anxiety’ A term introduced by Chantler et al, 2001 to express the discomfort of practitioners working with race and their fear of being labelled ‘racist’ and was also found more recently re: FMPO Privileging culture over gender runs the risk of overlooking violence and abuse as it is presented as a cultural issue and therefore not amenable to intervention Limitations of ‘culturally sensitive’ practice – what about gender and other social divisions? Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm Shame and Honour VAW in minoritsed communities often badged as ‘cultural’, but not in majority cultures – and this is problematic VAW constructed as an aberration in majority cultures, but as a norm in minority cultures Available information shows that VAW happens in all communities so this challenges the notion of cultural specificity – and of cultural ‘others’ Are honour and shame restricted to particular communities? ‘Race’ anxiety, shame and honour Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm Razack’s critique of Wikan 13 Problematizing feminsim Implication that westerners have values (liberal, egalitarian) whilst Muslims have cultures (oppressive, patriarchal) Over determining culture obscures structural relationships based on ‘race’ and class Implicit in Wikan’s work is the self-image of the West as ‘outside’ of culture (Razack, 2004) Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm Which Communities? (Hester et al 2007) Main Community Targeted Number % South Asian 43 37.4 Somali 20 17.4 Other African 19 16.5 Middle Eastern 17 14.8 Chinese 9 7.8 Latin American 7 7.1 115* 100 Learning Disability and Forced Marriage (Ann Craft and Judith Trust) • Children & adults with learning difficulties more likely to be abused than their peers (Sullivan, P. and Knutson, J. 2000) • Difficulties of consent (both for person with LD and their potential spouse) • Motivation: can be benign, but still an abuse of human rights • Gender: roughly equal numbers of men and women • Specific guidelines (2010): https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo ads/attachment_data/file/35533/fm-disabilityguidelines.pdf Routes into Forced Marriage (Hester et al 2007) • • • • • Financial Social (gender inequalities) Sexuality (compulsory heterosexuality) Child marriage (and what is a child?) Immigration (works both at the point of entry and to restrict exit) Poverty/Financial • Use of women as commodities (bride price in African communities intersects with ‘consent’ ) • Poverty is the major thing…if she [prospective in-laws] gives money, the family won’t ask [for the young woman’s consent]…the money will buy rice for them. …. Because of money, they will send their kids [for marriage]. • Poverty in Chinese contexts – sale of women for marriage Poverty/Gender/Immigration 18 “ I was pregnant at the time and he drinks, so one day I asked him where he was as I as taking his shoes off, you have to take his shoes off, socks off everything, sometimes soak his legs, and I asked him where he was and he didn’t reply so I asked him again and the next thing he hitted me on my face, I couldn’t believe this and again the next one, I didn’t say anything he said how dare you ask me I didn’t get married so you could ask me, you live under my roof, you have to obey my rules I paid money for you and your father knows you are here and you were given to me… and I kept quiet…so I prepared the food, still crying and he ate and went to bed” Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm VAW & Asylum “Even if this country [UK] reject me I don’t know where I will go…it will be my dead body going back [to Africa]. I tried to commit suicide twice…I keep a diary in case and leave it where someone can find in case I die…“I will kill myself before I go back to Africa…I am ready for that…It’s really too much…at any time they can call me and say we are going to deport you…I live life by the day”(M19). (‘Failed’ asylum seeker, Hester et al, 2007) Connect Centre for International Research on Interpersonal Violence and Harm Compulsory Heterosexuality • I will take that one step further and say in what community do we not see the pressure of marriage, yeah, I would say that we as a society are trained, from a very young age to believe that there are particular roles we need to fulfil and the other aspect of our life is that we want to fulfil those roles. (Interviewee, Hester et al 2007) • I guess for me I wouldn’t necessarily see that as just peculiar to this community …I think that that’s happened in white communities and majoritised communities as well…if you get married then that will iron out all the, the bumps of your sexuality so to speak and frankly that saying isn’t it, all she needs is a good… husband wedding. (FG Participant, Hester et al, 2007) Child Marriage • A man who is forty-five, marrying a sixteen year or seventeen year old, is not marrying a wife. He’s marrying a… slave. Someone he can control. Someone he can tell to do what he wants to do when. Somebody who doesn’t know where to find help. Someone who is locked in the house as he goes to work. You know it’s just a way of, child abuse (Interviewee, Hester et al, 2007) Immigration • Improving career and life chances (Foreign nationals and UK nationals) • Milbank and Dauvergne (2011): vulnerable brides as ‘ours’ (nationals or dual nationals) and imposed grooms as ‘theirs’ (migrant spouses), so eliciting an immigration response to FM • Women forced into marriage in non EC countries and now claiming asylum in the UK on the basis of gender persecution. • Trafficking of women for marriage – illegal immigration Impact of Forced Marriage: Self-harm It’s like something comes into you, You don’t feel scared of killing yourself you get so fed up, so much abused, you don’t care about anything, how much you’re going to hurt yourself. There have been times I would have liked to stab myself but they’d hidden all the knives. I was craving for a knife to put inside me just wanted to finish myself – no other way out. I was always thinking about killing myself, feeling I had to. It was like I was in hell.” (Survivor, aged 15 at the time of second forced marriage, Chantler et al, 2001) • Self-harm also emerged in survivor accounts in our Hester et al study (Hester et al 2007) • Bhui et al (2007) review of literature on rates, risk factors and methods found a link between ‘arranged marriages’ and self-harm Exiting a Forced Marriage • Most attention is paid to entry into rather than exit from force marriage • Need to consider both • No recourse to public funds – financial barriers, fear of deportation, asylum • Stigmatisation of divorce for women • Gendered surveillance post marriage Forced Marriage in Asylum Cases • Forced Marriage frequently presented as a case within asylum claims • FM as a human rights issues not seriously considered in asylum cases (survivor accounts) • Treated differently in different fields of social policy • Impact of such contradictions is that victims are often left unprotected Legal Measures • Debates on criminalisation (two consultations) • Civil Protection – Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007 – Nov. 2008 • Raising the age of marriage and sponsorship (for non EU spouses) to 21 – implemented Nov 2008, withdrawn 2011 (ruled unlawful) • Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act (2014) has made: i) FM a criminal offence and ii) the breach of an FMPO a criminal offence FM Civil Protection Act (2007) • Courts have power to make Forced Marriage Protection Orders. • Breach of an injunction was not originally a criminal offence, but a contempt of court. Courts have the full range of sanctions available to them, including imprisonment. • Enables people to apply for an injunction at the county courts, rather than just the high courts FM Civil Protection Act (2007) • Forced Marriage Protection Orders – applies to children and adults • Enables victims to apply for an order • Relevant third party can apply on behalf of victim • Places FMU Guidelines on a statutory footing. • Forced marriage similar to (and sometimes is) child abuse or domestic violence • SSD has a duty to investigate under s.47 Children Act 1989 to protect children Conclusions • Focussing on routes in to and out of forced marriage promises more than a culturalist framing • Beware of how legitimate concerns of VAW/FM can be i) co-opted by the state; ii) used to reinforce the superiority of the West • FM treated differently in different fields of social policy resulting in victims often left unprotected • The mental health impact of FM should not be underestimated • There needs to be increased recognition and intervention in FM – cuts to (BME) women’s organisations unhelpful • Further research Reading/Resources (FM) • Anitha, S. and Gill, A. (2009) Coercion, Consent and the Forced Marriage Debate in the UK, Feminist Legal Studies 17 pp 165-184 • Brandon, J. & Hafez, S. (2008) Crimes of the Community: Honour Based Violence in the UK, Centre for Social Cohesion • Chantler, K., Gangoli, G. and Hester, M. (2009) ‘Forced Marriage in the UK: Religious, Cultural,’ Economic or State Violence? Critical Social Policy (November) • Gill, A. and Anitha, S. (eds) (2011), Forced Marriage: Introducing a social justice and human rights perspective. London: Zed. • Gangoli, G & Chantler, K. (2009) Protecting Victims of Forced Marriage: Is Age a Protective Factor? Feminist Legal Studies vol. 17, no. 3 pp 267-288 Reading/Resources (FM) • Hester et al (2007): Forced Marriage: the risk factors and effects of raising the minimum age for a sponsor and of leave to enter the UK as a spouse or fiancé(e): http://www.bris.ac.uk/sps/research/projects/completed/2007/rk66 12/rk6612finalreport.pdf • Gangoli, G., Chantler, K., Hester, M & Singleton, A (2011) ‘Understanding Forced Marriage: Definitions and Realities’. In A. Gill and A. Sundari (eds) (Ed.), Forced Marriage: Introducing a social justice and human rights perspective. London: Zed. • Chantler, K. and Gangoli, G. (2011) ‘Domestic Violence in Minority Communities’: Cultural Norm or Cultural Anomaly?’ In R. Thiara, M. Schroettle & S. Condon (eds) (Ed.), Violence against Women and Ethnicity: Commonalities and Differences across Europe Reading/Resources (FM) • Chantler, K. (2014) ‘What’s love got to do with Marriage?’ Journal of Families, Relationships and Society, Vol 3(1) pp. 19-33 • Chantler, K. (2012)Recognition of and Intervention in Forced Marriage, Journal of Trauma, Violence and Abuse 13 (3) pp 176-183 • Kazmirski et al (2009) Prevalence and Service response. Available at: http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/ DCSF-RR128.pdf • Forced Marriage Unit: fmu@fco.gov.uk Making Research Count: Forced Marriage Research, Policy and Practice Dr. Khatidja Chantler Reader, School of Social Work Email: kchantler@uclan.ac.uk