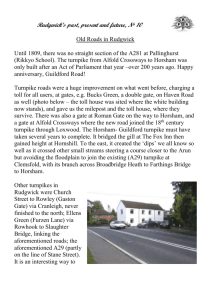

accounting on the road: turnpike adminis

advertisement