PDF - Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of the

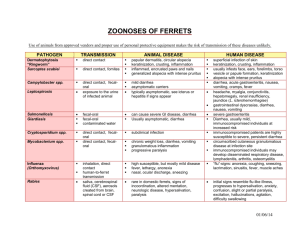

advertisement

Taming the Beast: Diarrhea Juliet Sio Aguilar, M.D., M.Sc.(Birm) Professor of Pediatrics University of the Philippines Manila Active Consultant, St. Luke’s Medical Center • “Glocal” Burden • Local Epidemiology • Diagnostic Decisions • Treatment Options • Preventive Strategies Outline: Taming Killer Diarrhea Global Burden of Diarrhea Black RE et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010; 375: 1969-87. Global Deaths from Diarrhea Black RE et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010; 375: 1969-87. 11.3% of total deaths in children 1-59 mos Every year ~5000 diarrheal deaths Everyday ~13 young children dying Local Burden of Diarrhea Black RE et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010; 375: 1969-87. World Health Organization. Mortality Country Fact Sheet 2006.. • Underlying cause of under-5 mortality (WHO estimates, 2000-2003) • 53% of ALL deaths • 61% of deaths due to diarrhea globally • 80% of children with diarrhea die during the first 2 years of life Malnutrition and Diarrheal Diseases Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE, WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet 2005: 365:1147-52. DOH. Field Health Service Information System Annual Report 2007. DOH. Field Health Service Information System Annual Report 2007. 3-28% of all diarrheal episodes (de Andrade and Fagundes-Neto, 2011) Highest incidence in the 1st 2 years of life • 10% of acute diarrhea cases in Philippines become persistent (Santos Ocampo et al, 1988) • Highest prevalence in the 1st year of life with 63% of cases (Santos Ocampo et al, 1988) (Black, 1993) Persistent Diarrhea Most Common Microorganisms Reported for Acute Endemic Diarrhea among U5 Children in Developing World All Episodes < 2 years Rotavirus EPEC,ETEC Astrovirus, Caliciviruses, enteric Adenovirus Shigella flexneri, Shigella dysnteriae type 1 Campylobacter jejuni ETEC, EAEC 2-5 years ETEC S. flexneri, S. dysenteriae type 1 Rotavirus Non-typhi Salmonella Giardia lamblia Watery Mucous < 2 years Rotavirus EPEC,ETEC Astrovirus, Caliciviruses, enteric Adenovirus Shigella flexneri, Shigella dysnteriae type 1 Campylobacter jejuni ETEC,EAEC 2-5 years ETEC Shigella flexneri, Shigella dysenteriae type Rotavirus O’Ryan M, Prado V, Pickering LK.Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2005; 16: 125-36. Burden of Rotavirus Disease (Global RV Surveillance Network) Rotavirus Surveillance – Worldwide, 2009. MMWR 2011; 60(16): 514-6. Etiologic Agents of Acute Diarrhea in selected Philippine Hospitals Paje-Villar et al,. PJP 1993; 42: 1-24. Adkins HJ et al. J Clin Microbio 1987; 25: 1143-7. San Pedro MC, Walz SE. SEAJTMPH 1991; 22: 203-10. % Prevalence of Rotavirus Disease Carlos C et al. J Infect Dis 2009; 200 (Suppl 1): S174-81. Bacteria E. coli (EAEC; EPEC) Campylobacter spp S. enteritidis Shigella spp C. difficile Klebsiella spp Protozoa G. lamblia B. hominis* Cryptosporidium spp* E. histolytica Cyclospora cayetanensis* Microsporidium spp* Viruses Astrovirus Enteroviruses Picornaviruses *particularly associated with HIV Etiologic Agents for Persistent Diarrhea De Andrade JA , Fagundo-Neto U. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2011; 87: 188-205. • Diagnosis for most cases of acute diarrhea: clinical • Based on the clinical syndromes • Acute watery diarrhea • Bloody diarrhea • Persistent diarrhea • Diarrhea with severe malnutrition • Routine stool examination not necessary in most cases of acute watery diarrhea • Stool microscopy and culture indicated only when patients do not respond to fluid replacement, continued feeding, and zinc supplementation Diagnostic Investigations • Ascertain if due to an infection • 40-60% due to shigellosis • Empiric treatment with ciprofloxacin 15 mg/kg/dose BID for 3 days • Consider differential diagnosis • Anal fissure • Intussusception • Allergic colitis Bloody Diarrhea • Diagnosis made on clinical grounds (onset and duration of diarrhea) • Most of the cases (> 60%) due to: • Acute intestinal infection • Dietary intolerance • Protein-sensitive enteropathy (cow’s milk) • Secondary disaccharide malabsorption (lactose) • In 30% of cases, no etiologies can be established despite extensive investigations. Persistent Diarrhea Bhutta et al. JPGN 2004; 39: S711-16. Mainstays in Diarrhea Management • Malnutrition underlie 61% of diarrheal deaths globally. • Micronutrient deficiencies • • • • Diminish immune function Increase susceptibility to infections Predispose to severe illnesses Prolong duration of illness Micronutrient Supplementation in Diarrheal Disease • Early studies: single nutrients • To combat diarrhea, respiratory infections, and anemia • To improve child growth and development • Recent studies: multiple nutrients • Increasing recognition that micronutrient deficiencies do not occur in isolation • Multiple MNS may be more cost-effective Single vs. Multiple Nutrient Supplementation (MNS) Ramakrishnan U, Goldenberg T, Allen LH. Do multiple micronutrient interventions improve child health, growth, and development? J Nutr 2011; 141: 2066-75. Therapeutic Strategy • Zinc • Vitamin A • Folic acid Preventive Strategy • Zinc • Vitamin A • Multiple micronutrients Single vs. Multiple Nutrient Supplementation Acute Diarrhea • Reduction in duration of -0.69 day [95%CI: -0.97 to -0.40] • Reduction in diarrhea risk lasting >7 days RR=0.71 [95% CI: 0.530.96] • No reduction in stool output • Based on 18 RCTs (n=11,180 mainly from developing countries) Persistent Diarrhea • Zinc (with MV vs MV alone; singly or with vitamin A) significantly • Reduced stool output • Prevented weight loss / promoted weight gain • Promoted earlier clinical recovery • Based on 2 RDBCTs in mod malnourished children 6-24 mos (n=190 + 96) Zinc Supplementation: Treatment Patro B, Golicki D, Szajewska H. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28: 713-23. Roy SK et al. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87: 1235-9. Khatun UH, Malek MA, Black RE….Roy SK. Acta Paediatr 2001; 90: 376-80. 1990s 2000s • Continuous trials (1-2 RDAs 5-7 times/week) • OR= 0.82 [95%CI: 0.72, 0.93] incidence • OR = 0.75 [95%CI: 0.63, 0.88] prevalence • Short-course trials (2-4 RDAs daily for 2 wks) • OR = 0.89 [95%CI: 0.62, 1.28] incidence • OR = 0.66 [95%CI: 0.52, 0.83] prevalence • 9% reduction in incidence of diarrhea • 19% reduction in prevalence of diarrhea • 28% reduction in multiple (>2) diarrheal episodes • No statistically significant impact on persistent diarrhea, dysentery or mortality Zinc Supplementation: Prevention Bhutta A, Black RE, Brown KH et al. J Pediatr 1999; 135: 689-97. Patel AB, Mamtani M, Badhoniya N, Kulkarni H. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 122. • Decline in protective efficacy due to variability in: • Microbial isolates • Klebsiella sp most responsive; E coli neutral; rotavirus worse outcome • Age • Less efficacious in infants <12 mos • More pathogens in those <12 mos which are refractory to zinc (e.g., rotavirus) • Zinc salts used • Zinc gluconate with most significant reduction in incidence in comparison to zinc sulfate and zinc acetate Zinc Supplementation: Prevention Patel AB, Mamtani M, Badhoniya N, Kulkarni H. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 122. • Inconsistent results as treatment adjunct • Beneficial only as prophylactic strategy Meta-analysis of 43 trials (215,633 aged 6m-5y) • Reduction in mortality from diarrhea RR=0.78 [95% CI: 0.57, 0.91] • Reduction in diarrhea incidence RR=0.85 [95% CI: 0.82, 0.87] • No significant effect on hospitalizations due to diarrhea • Increased vomiting within 48 hrs of supplementation RR=2.75 [95% CI: 1.81, 4.19] • Can ameliorate adverse effect of stunting associated with persistent diarrhea Vitamin A Supplementation Fischer Walker CL, Black RE. Micronutriennts and diarrheal disease. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:S73-7. Mayo-Wilson E, Imdad A, Herzer K, Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. BMJ 2011; 343: d5094 doi: 10.1136. Villamor E et al. Pediatr 2002; 109 (1). • RDBPCT on clinical efficacy of combination therapy vs. monotherapy among 6-24 mos with acute diarrhea (n=167) vs. control • Supplementation of zinc, zinc + vitamin A, and zinc + micronutrients (vitamin A + Fe, Cu, Se, B12, folate) vs. control • Comparable outcomes for supplemented groups with regards to duration, volume of diarrhea, and consumption of oral rehydration solution Vitamin A or MMN with zinc does not cause further reduction in diarrhea outcomes, confirming the clinical benefit of zinc alone in the treatment of diarrhea. MMN Supplementation: Treatment Dutta P, Mitra U, Dutta S et al. J Pediatr 2011; 159: 633-7. • Most studies in diarrhea prevention • No benefit in Peru, Indonesia, South Africa • South Africa • Lower diarrhea incidence only among stunted children when compared with vitamin A alone • Vitamin A + zinc RR=0.52 [95% CI: 0.45, 0.60] • MMN (with vit A, zinc) RR=0.57 [95% CI: 0.49, 0.67] MMN does not lower incidence of diarrhea except among stunted children when used with supplemental zinc. MMN Supplementation: Prevention Lopez de Romana G et al. J Nutr 2005; 135: S646-52. Untoro J et al. J Nutr 135; S639-45. Luabeya KA et al. Plos One June 2007 (6): e541 Chhagan MK et al. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009; 63: 850-7. Acute Diarrhea Persistent Diarrhea • Reduction in duration of diarrhea by 24.76 hrs [95% CI: 15.933.6 hrs] • Decrease risk for diarrhea lasting > 4 days with risk ratio 0.41 [95% CI: 0.32-0.53] • Small review of 464 subjects • Reduction in duration of diarrhea by 4.02 days [95% CI: 4.613.43] • Decrease in stool frequency Adjuncts in Treatment: Probiotics Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 Nov 10; (11): CD003048. Bernaola Aponte G et al.. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 Nov 10; (11): CD007401. • Individual patient data meta-analysis • 9 RCTs (n=1384) • Higher proportion of recovered patients in racecadotril group vs placebo • Hazard ratio = 2.04 [95% CI: 1.85-2.32] p<0.001 • Ratio of stool output between racecadotril/placebo • = 0.59 [0.51-0.74] p<0.001 • Ratio of mean number of diarrheic stools between racecadotril/placebo • = 0.63 [0.51-0.74] p<0.001 Racecadotril in Diarrhea Lehert P, Cheron G, Calatayud GA, Cezard JP et al. Racecadotril for childhood gastroenteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 44: 707-13. • Breast feeding • Improved weaning practices • Immunizations against measles, rotavirus and cholera • Improved water supply and sanitation facilities • Promotion of personal and domestic hygiene Strategies Cost/DALY US $ Breast feeding 930 Measles vaccination 981 Rotavirus vaccination 2,478 Cholera vaccination 2,945 Rural water and sanitation improvement 7,876 ORT 10,020 Urban water and sanitation improvement 25,510 Strategies for Diarrheal Disease Control Are breastfed babies protected against rotavirus disease? Case-control study in rural Bangladesh n=102 cases with clinically severe rotavirus diarrhea; n=2587 controls Results • eBF of infants associated with significant protection against severe rotavirus diarrhea; RR=0.10 [95% CI: 0.03,0.34] • NoBreastfeeding overall protection BF control during the is stillassociated importantwith for the of first 2 yearsdue of life; RR = 2.61 [95% CI: 0.62,11.02]. diarrhea to non-rotaviral enteropathogens. BF and Risk of Rotavirus Diarrhea: Prevention or Postponement? Clemens J et al. Pediatrics 1993; 92:680-5. Surveillance study in Muntinlupa (2005-2006) evaluating the burden of RV disease Significantly higher prevalence of RV infection among non-BF infants <6 mos [24% vs. 15%, p=0.04] No statistically significant difference in prevalence of RV infection between BF and non-BF infants (p=0.519) for children <5 yr old BF and Risk of Rotavirus Diarrhea Carlos CC et al. J Infect Dis 2009; 200 (Suppl 1): S174-81. Know what you’re up against… Utilize your resources well... Keep the beast at bay… Taming the Beast: Diarrhea