international marketing - İzmir Ekonomi Üniversitesi

advertisement

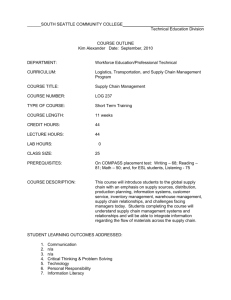

INTERNATIONAL MARKETING SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT HIGHER NATIONAL DIPLOMA Supply Chain Logistics: An Introduction : DL5E 34 / VSC 116 EĞİTİMCİ HAKKINDA BİLGİ ÖMER PESEN Darüşşafaka Lisesi mezunu Makine Mühendisi Tekstil & Pazarlama yüksek lisans – Bradford Üniversitesi / UK 29 yıldır dış ticaret ile uğraşıyorum 22 yaşında bir firma sahibiyim – ATCO Dış Ticaret Ltd. Şti. 12 yıldır eğitim veriyorum İzmir Ekonomi Üniversitesi’nde öğretim görevlisiyim Cep : 0542 533 15 35 E-mail : opesen@superonline.com DURING THE COURSE …… 1xMid-term Exam 20% ( Questions + Cases ) Class / Homework Assignments 20% Single or Group work – evaluated as quizes ( Q1,Q2,Q3,Q4,....) 1xPresentation 30% Sectoral Project – Field work Final Exam 30% ( Questions + Cases ) DURING THE COURSE …… Attendance is very very important for you . We will learn in the class . You will be responsible from everything discussed and said in the class . No talking in the class . Anybody wants to talk with friends can do this without any problems outside . I need people who wants to learn something from a businessman . No attendance in class work , no evaluation and no second chance . WHAT IS THE COURSE ABOUT ? Supply Chain Logistics Logistics and Service Operations Logistics and Customer Scheduling Materials Management in Services Supply Chain Management Supply Chain Relationships Logistics and Customer Needs Logistics and Operations Management The Marketing Mix Customer Relationship Management Logistics: The Value Chain Logistics and Cost Classification Distribution Logistics Warehouse Operation Reverse Logistics INTRODUCTION This unit Supply Chain Logistics: An Introduction will assist you to become familiar with the basic logistics’ concept and have an understanding of how they are used in the management of the supply chain. You should also be able to demonstrate the role played by the customer in organising the logistics to meet customer needs as well as the importance of managing the supply chain operations to provide value to the organisation. INTRODUCTION There are three outcomes for this unit: Identify the competitive advantages that can be obtained through the application of logistics. Describe the customer role in determining how the logistics are organized to meet the customer needs. Explain how logistic costs can be managed to provide value to the stakeholders HOW TO FOLLOW ..... Sections 1- 6 This first part of the Unit should enable you to describe the competitive advantages that can be achieved through the application of Logistics. This part will cover: Definition, structure and purpose of a supply chain Relationships in a supply chain Customer needs Definition of logistics Performance objectives of the supply chain Competitiveness of the supply chain Logistics strategy HOW TO FOLLOW ..... Sections 7- 10 The second part of the Unit should enable you to describe how the customer has a strong influence on the design and organisation of the Logistics process to meet their needs. This part will cover: Customer service levels Marketing mix Order winners and qualifiers Logistics contribution to marketing Customer relationship management Customer retention HOW TO FOLLOW ..... Sections 11-15 The third part of the Unit should enable you to explain the management and control of Logistics costs in order to provide value to the stakeholders. These sections will cover: Return on assets (current assets, fixed assets, sales, profit margin, price) Value added Standard costing Activity based costing Supply Chain Logistics Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Supply Chain Management Supply Chain Management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all Logistics Management activities. Importantly, it also includes co-ordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, and customers. In essence, Supply Chain Management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Supply Chain Management: Boundaries & Relationships Supply Chain Management is an integrating function with primary responsibility for linking major business functions and business processes within and across companies into a cohesive and high-performing business model. It includes all of the Logistics Management activities, as well as manufacturing operations. In addition it drives co-ordination of processes & activities with and across: Marketing Sales Product design Finance Information technology. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Logistics Management Logistics Management is that part of Supply Chain Management that plans, implements, and controls the efficient, effective forward and reverse flow and storage of goods, services and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption in order to meet customers' requirements. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Logistics Management: Boundaries & Relationships Logistics Management activities typically include: inbound and outbound transportation management fleet management warehousing materials handling order fulfilment logistics network design inventory management supply/demand planning management of third party logistics services providers. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions To varying degrees, the logistics function also includes sourcing and procurement, production planning and scheduling, packaging and assembly, and customer service. It is involved in all levels of planning and execution: strategic, operational and tactical. Logistics Management is an integrating function, which co-ordinates and optimises all logistics activities, as well as integrating logistics activities with other functions including marketing, sales manufacturing, finance and information technology. So in essence Logistics presents a big challenge to organisations, but done right a source of competitive advantage. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Example A large supermarket chain continues to grow in an intensely competitive market. Why is this the case? This organisation describes its core purpose as being to create value for customers to earn their lifetime loyalty. To do this the organisation must: understand its customer needs and how they can best be served ensure their products are recognised by its customers as representing outstanding value for money ensure that the products, required by its customers, are available on the shelf at each of its stores at all times, day and night. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions The task of planning and controlling the purchase and distribution of this organisation’s huge product range from suppliers to stores falls to Logistics. Logistics is the task of providing: Material Flow of the physical goods from suppliers through the distribution centres to stores Information Flow of the demand data from the consumer back to purchasing and to suppliers so that material flow can be accurately planned and controlled. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions The logistics task of managing material flow and information flow is a key part of the overall task of supply chain management. Supply chain management is concerned with managing the entire process of raw material supply: the manufacturing, packaging and distribution to the end customer. This particular supermarket chain supply chain structure comprises three main functions: Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Distribution is the operations and support task of managing the distribution centres (DC’s), and the distribution of products from the DC’s to the associated stores Network and Capacity Planning is the task of planning and implementing sufficient capacity in the supply chain to ensure that the right products can be procured in the right quantities now and in the future Supply Chain Development is the task of improving the overall supply chain so that its processes are stable and in control, that it is efficient, and that it is correctly structured to meet the logistics needs of material flow and information flow. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions So we can see logistics plays a large part in the overall supply chain challenge acting as a key enabler. The alignment of the various partners in a supply chain is critical in order to deliver superior value to the end customer at less cost to the supply chain as a whole. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Management Strategy The focus of management strategy for the supply chain as a whole is on alignment between supply chain members, of which the end customer is the key one. As Gattorna (1998) puts it: Materials and finished products only flow through the supply chain because of consumer behaviour at the end of the [chain]. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions The proper management, of material flow and information flow, along the supply chain is critical in influencing the consumer satisfaction with the end product. Late or wrong delivery, or missing bits from a product, can put the whole supply chain at risk from competitors who can perform the logistics task better. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions If we go back to our example we can see the large supermarket chain is in no doubt about the opportunities here. A breakdown of costs in their UK supply chain is as follows: Supplier delivery to distribution centre (DC) DC operations and deliver to store Store replenishment Supplier replenishment systems 18% 28% 46% 8% Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Nearly half of the supply chain costs are incurred in-store. In order to reduce these in-store costs, they have realised that the solution is to spend more upstream and downstream to secure viable trade-offs in store replenishment. In simple terms if a product is not available on the shelf, then the sale is lost. By aligning external manufacturing and distribution processes with its own, they seek to deliver superior value to the consumer at less cost to the supply chain as a whole. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Material Flow The aim within a supply chain must be to keep materials flowing from source to end customer in a timely and regulated manner. Supply Chains can be complex with many organisations involved, therefore it is essential that the material flow be properly managed as a process. This will help prevent local build-ups of inventory and material shortages at points in the chain. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions A company that produces motorcars, for example, will have thousands of components and sub-assemblies distributed through the supply chain, at any point in time. Yet these must be co-ordinated to come together for final assembly in order to ultimately deliver a gleaming car to the end consumer. Figure1: Simple example of a Supply Chain Figure1: Simple example of a Supply Chain Figure 1, above illustrates in simple terms the supply chain and its lower level suppliers. In real terms for a motorcar it is probably much larger which in turn introduces complexity. A key challenge is managing this complexity through the effective co-ordination of the different suppliers to deliver material on time to the next step in the chain. A key enabler to reducing the complexity is the effective management of information flow between the various tiers of suppliers. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions Information flow Synchronising material flow and movement however is only part of the equation. Another fundamental requirement is the timely and accurate flow of data and information down and across the various levels of the supply chain. Ultimately it is the demand of the end customer that triggers the supply chain to respond. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions By sharing the end-customer demand information across the supply chain, we create a demand chain, directed at providing enhanced customer value. Information technology enables the rapid sharing of demand and supply data at increasing levels of detail and sophistication. The aim is to integrate such demand and supply data so that an increasingly accurate picture is obtained about the nature of business processes, markets and consumers. Such integration provides increasing competitive advantage. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions The greatest opportunities for meeting demand in the marketplace with a maximum of dependability and a minimum of inventory come from implementing such integration across the supply chain. In today’s integrated world organisations cannot become ‘world class’ by themselves. Let us look again at the motorcar example to see how this is applied. Figure 2: Example of a Demand Chain Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Typical Definitions The data and information is often referred to as the glue that binds the supply chain processes together. Competing through Logistics Organisations of today have to be adept at managing a number of goals and objectives to be successful. Often these goals and objectives appear to be at conflict with one another. For example an organisation does not want to incur the monetary cost of carrying a high level of inventory but at the same time it must carry enough in order to be responsive on delivery to any reasonable rise in unforecasted customer demand. Against this backdrop customers, once they have decided to purchase, typically want the product or service now and at minimum cost. These factors have a strong influence on the design of the supply chain. Competing through Logistics To be successful and gain that crucial competitive advantage the various partners must come together to identify the critical success factors for the supply chain as a whole and the key capabilities they must each individually have or develop through investment in training, processes, quality etc. Competing through Logistics Organisations cannot do everything all of the time. They have a finite level of resource that means they have to develop their ability to prioritise and focus on the right activities. This brings us back to the need for alignment across the supply chain. Let us look at the competitive priorities that can be delivered by logistics in the supply chain. Competitive Advantage There are various ways in which products compete in the marketplace. For example; Quality Price Technical features Brand name Competitive Advantage Product availability in the marketplace at low cost is a key advantage provided by logistics, as shown in the supermarket chain example. Logistics supports competitiveness of the supply chain as a whole by: …meeting end customer demand through supplying what is needed, in the form it is needed, when it is needed, at a competitive cost. The Quality Advantage The most fundamental objective, in that it is a foundation for all the other, is to carry out all processes across the supply chain so that the end product does what it is supposed to do. Quality is the most visible aspect of the supply chain. Business processes must be designed to not just meet the needs of customers, but to delight them. The Quality Advantage Many things influence customer loyalty: product does what it is supposed to do value for money quality of processes way the customer is treated quality of the staff in the organisation organisation makes a commitment and keeps that commitment The Quality Advantage Product unavailability, defects and late deliveries are all symptoms of quality problems in supply chain processes. Such problems are visible to the end customer, and negatively influence that customer’s loyalty. The Quality Advantage Robust processes are at the heart of supply chain performance. Through the adherence to process management, defects or errors will be highlighted earlier reducing the impact on customer and cost. Commitment to quality and a customercentred attitude must start at senior management and permeate down through, all levels of the organisation and every organisation in the supply chain. The Speed Advantage The time a customer has to wait to receive a given product or service is measured. Volkswagen calls this time the customer lead-time: that is, the time it takes from the moment a customer places an order to the moment that customer receives the car they have specified. Such lead-times can vary from zero (the product is immediately available, such as goods on a supermarket shelf) to months or years (such as the construction of a new building). The Speed Advantage Companies that have learned that some customers don’t want to wait can use time to win orders. They are prepared to pay a premium to get what they want quickly. An example is Vision Express, which offer prescription spectacles, ‘in about one hour’. Technicians machine lenses from blanks, on the premises. Staff are given incentives to maintain a 95% service level against the one-hour target. Vision Express has been successful in the marketplace by re-engineering the supply chain so that parts and information can flow rapidly from one process to the next. Compare this with other opticians in the high street, who must send customer orders to a central factory. The Speed Advantage Under the remote factory system, orders typically take about 10 days to process. An individual customer’s order must be dispatched to the factory and then compete in a queue with orders from all the other high street branches around the country. Once it has been processed, it must return to the branch that raised the order. While this may be cheaper to do (a single, remote factory replaces many small factories in the branches), it takes much longer . The Dependability Advantage Time is not just about speed. It is also about meeting promises. Organisations can do themselves a power of good by adopting one clear but very simple message: make a promise and keep that promise. Questions an organisation should be asking itself: are we always meeting our delivery promises do we answer calls when we said, how we said and answer what the customer wanted reflect the right standards and commitments, can I make promises knowing that the company will be able to fulfil them. The Dependability Advantage Firms who do not offer instantaneous availability need to tell the customer when the product or service will be delivered. Delivery dependability measures how successful the firm has been in meeting those promises. For example, the UK based Royal Mail offers a first class service for letters where there is a 92% chance that a letter posted today will reach its destination tomorrow. The Dependability Advantage It is important to measure dependability in the same end to end way that speed is measured. Although Vision Express offers a one-hour service for prescription glasses, the 95% service level target is a measure of the dependability of that service. Dependability measures are widely used in industries such as train and air services to monitor how well published timetables are met. In manufacturing firms, dependability is used to monitor a supplier’s performance in such terms as: > On time (% orders delivered on time) > In full (% orders delivered complete) The Dependability Advantage An organisation needs robust and predictable processes to provide the foundation for supply chain processes. This is no different for dependability if the organisation wants to gain an important advantage. Toyota UK manages inbound deliveries of parts from suppliers in southern Europe by a process called chain logistics. Trailers of parts are moved in four-hour cycles, they are then exchanged for the returning empty trailer on its way back from the UK. The Flexibility Advantage While doing things the same way at the same time may be good from a point of view of keeping costs down, few markets are in tune with such an idealised way of doing business. A supply chain needs to be responsive, to new products and markets, and to changing customer-demand. This means in turn that it must be capable of changing what is done. The Flexibility Advantage Flexibility takes four forms: Product Flexibility which measures how quickly a new product can be introduced Mix Flexibility which measures the time it takes to change between different products in a given range. Volume Flexibility which measures the time it takes to respond to increases or decreases in overall demand Delivery Flexibility which measures the ability to change deliveries (intentionally) by bringing them forward or pushing them back. The Productivity Advantage Cost is important for all supply chain processes. Low costs translate into advantages in the marketplace in terms of low prices or high margins, or a bit of both. Many products compete specifically on the basis of low price. From a supply chain point-of-view this may translate into low-cost manufacture, distribution and servicing. The Productivity Advantage Examples of products that compete on low price are supermarkets’ own brand goods that reduce the high margins and heavy advertising spend of major brands. They also perhaps cut some of the corners in terms of product specification in the hope that the customer will consider low price as being more important than minor differences in product quality. The Productivity Advantage The pressure to reduce prices at car component suppliers is intense. The assemblers have been setting annual price reduction targets for their inbound supply chains for some years. Unless a supplier can match reduced prices for which products are being sold, by reducing costs, that supplier will gradually go out of business. As a result, many suppliers are cynical about the price down policies of the assemblies. The Productivity Advantage The benefit of cutting costs is reduced prices, often a collaborative effort on the part of several partners in the supply chain. Tesco can make only limited in-roads into its in-store costs without collaboration from its supply chain partners. Many small UK dairy farmers are being forced out of business, because the price of milk in supermarkets is less than the price of water. For them, there are few opportunities to cut costs. The Productivity Advantage Logistics is not the only way in which product competitiveness in the marketplace can be enhanced. The five performance objectives listed above can be added to (and in some cases eclipsed by) other ways in which products may win orders, such as design and marketing features. Thus superior product or service design, often supported by brand image, may create advantage in the marketplace, as it does for BMW cars and the Dorchester Hotel, for example. The Productivity Advantage Here, the logistics task is to support the superior design. BMW’s supply chain is one of the most efficient there is, mainly because its products are sold (at least in Europe) as soon they have been made. Finished cars do not accumulate in storage on airfields like those of the mass producers. Storing finished products adds cost, with no value to the end consumer. Logistics and Service Operations The Design of Service Operations In terms of “what, how, how much and where”, the designer of a service has to confront similar issues to that faced in manufacture. It is necessary though, to think through the consequences of having the customer as part of the delivery system. If the Operations Manager can reduce the sources of uncertainty in the delivery system, by making it more predictable, then the system becomes easier to manage and control. What then, are the sources of this uncertainty, and to what extent can they be reduced? The Design of Service Operations We must also differentiate between the Front Shop Operations, which for the customer represent the organisation, where service encounters must be sensitively managed, and the Backroom Operations, the other 90% of the organisational iceberg, which has more in common with manufacture, and of which the customer is blissfully unaware. Service as Product We have already referred to the service bundle in terms of the tangible benefits, sensory benefits and psychological benefits it seeks to provide. It is vital that the organisation does not take too narrow a view of what it does, otherwise what the customer wants (in the holistic sense), may not be what is supplied. Charles Revlon of Revlon summed it up in saying: “…in the factory we make cosmetics, in the store we sell hope…” Service as Product It is particularly important that service encounters are properly managed, requiring appropriate levels of social and technical competence on the part of the staff delivering the service. It is essential that there is an overall coherence in terms of the expectations created, and what is actually delivered in terms of the components of the service bundle, not all of which are completely within the gift of the organisation’s management. Service as Product Manufacturing has learned the lesson of attention to detail being a prerequisite for a successful product, of identifying needs, that sometimes the consumer has been unable to articulate, and of carefully monitoring feedback on a product’s acceptability. The service sector needs to apply a similar approach. Capacity The operations manager in a high contact system is faced with managing uncertainty on two fronts. Firstly, the initiative in establishing contact with the service provider lies with the customer, leading inevitably to lumpy and unpredictable demand. Secondly, although there are expectations, the time the customer spends within the system is often at the customer’s discretion. In services, you cannot buffer yourself from demand uncertainty by using stock as can manufacturing. Capacity The implication is that the organisation has four pure strategies open to it: maintain slack capacity (fire service) adjust capacity to meet demand where possible (DIY Warehouse) manage demand by for instance differential pricing substitute capital for labour (auto-tellers) Capacity In practice firms use a mix of the above strategies. In manufacturing, there is the dilemma of, lost business due to a lack of capacity, against the costs of maintaining excess capacity. Organisations should be aware of the costs’ sensitivity of the trade-off, in terms of the probabilities of particular levels of demand and revenue, against the costs of carrying capacity. Technology of Transformation As the drive for improved service and greater productivity continues, we can be quite sure that organisations will be making greater use of increasingly sophisticated technology. Technology can either enhance or compromise the service encounter, depending on the context and the nature of technology employed. It can for instance empower the customer, allowing them to conduct the encounter at their own pace, and in privacy. For example computer-based diagnostics, where the patient responds to a series of gentle prompts from the screen, have proved surprisingly acceptable. Technology of Transformation Library book search packages are another good example. Technology can also be a barrier in the transaction if the user is unfamiliar with it, or if perhaps information is accessible to the service provider rather than the user. Have you ever wondered what information the bank teller has on you and your account on the screen that only he/she can see? It would be useful at this point to use the classification of productive systems to the service context: 1- Job Shop 2- Line 3- Location Job Shop Volume for a service that has low volumes of identical outputs and considerable variety in characteristics Service Change Service changes readily accommodated. Demand Variation Lumpy or uncertain demand accommodated Market Type Custom service to order Task Characteristics Tasks with low specifically accommodated, difficult to acquire skills and uncertain, variation completion times. Job Shop Technology of Transformation Permits capital intensity using general purpose equipment Labour Skills Broad & variable skills and high degree of flexibility required Work Environment Un-paced individual work, craft skill specialist, long-term assignments Productivity Labour is inevitably less efficiently utilised in a variety of tasks Capacity Capacity is ill-defined but flexible within broad limits. As demand approaches capacity limits, in-process inventory tends to block system Line Volume Suited to high volume standardised service Service Change Change is costly since the entire process must be changed or at least rebalanced with each service change Demand Variation Best suited to stable demand without heavy cyclic influences Market Type Standardised service Task Characteristics Tasks with high specificity, well-defined, divisible, teachable and of predictable duration Line Technology Of Transformation Permits process automation via custom built equipment Labour Skills Tolerance of repetition Work Environment Highly visible, paced performance, productive unit tightly coupled Productivity Given stable demand, typically high due to division of labour and specialisation Capacity Capacity is well defined and understood, but expensive to change due to the pervasiveness of any change made Location Location is crucial to the high-contact service organisation. There is no escape from a sub-optimal location decision; it must by definition (unless the service provided is very specialised indeed) be driven by market requirements. Low-contact services can be more readily characterised as footloose, as information technology releases them of the requirement to be physically close to their customer. Location Firms in the high-contact sector will carry out exhaustive analysis on: Customer behaviour and their willingness to travel The demographic makeup of a designated catchment area Forecast changes over the next decade or so Availability of communications, such as road access (the local shopping centre) The existence of competition Location The existence of providers of complementary services to provide synergy. For example, many retail multiples will only locate to a new shopping development if they know that firms such as Marks & Spencer’s have taken the decision to locate there. It is sometimes said that the three most important factors in retailing are location, location and location. An oversimplification, perhaps, but with more than a grain of applicability to high contact services. WHAT IS A CASE ? What is a case ? A case is a written description of a business situation or problem . It generally provides factual information about a company’s background , which often includes organizational or financial data related to the present situation . The use of case analysis in teaching was developed by the Harvard Business School in the 1920s with the purpose of introducing the highest possible level of realism into teaching management decision making . What is a case ? A case raises contemporary issues and provides information to analyze from a business perspective . Also , often included in a case is information that is outside of the immediate company , which is related to the sociocultural , political , legal , technological and competitive environments . Data related to such industry sectors as apparel or fashion are described to give the reader a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding the situation . What is a case ? It is your job to propose solutions to the problems . In some circumstances , the case authors have purposely presented cases with no readily identifiable problem , just facts to sift through to arrive at the problem . The case study method is an active , problem-solving way of learning in which you have to think about the problem , use the facts provided in the case and then decide on the most appropriate action to take . External environmental factors (those outside the company) should also be considered , along with the specific internal facts about the company and the situation . What is a case ? The cases themselves can also help you to improve your reading , writing and speaking abilities , which are vitally important for good communication in business . Additionally , exposure to others’ thoughts and reasoning (such as those characters portrayed in the cases) can open your mind to other views . CASE ANALYSIS Case Analysis When analyzing a case , you should assume the role of the challenged individual in the case and react as you believe that person should , to best remedy the problem . As in all problem situations , there never is a single solution , nor a right or wrong answer . So, your recommended best alternative relies on and should be based on the facts contained within the case , along with the basic concepts and/or priciples provided in the case . Case Analysis Often it may seem that you don’t have enough information to solve the case problem . Welcome to the real world of business ! Often , decision makers do not have all the information needed for a “good” decision . But they must make a decision with the information available at the time . Case Analysis When a group approach to case analysis is used , students must understand that participation by everyone is absolutely necessary for this approach to be effective . Assuming that you are a part of a management team charged with a problem to solve may also help to motivate everyone in the group to participate . Case Analysis It is also important to remember that using common sense may help you to realize what is relevant for solving a case . Logic is another tool you will find helpful . Used in tandem with management concepts and principles , logic will also assist you in formulating your plan of action and your arguments and justifications for the selection of the best alternative solution . A RECOMMENDED APPROACH FOR CASE SOLUTION A Recommended Approach Read the case completely through , along with the major question . Reread the case and any accompanying illustrations or data carefully and do the following : Clearly define the immediate problem to be solved , if it is not already done for you Develop several alternative solutions to the problem and that could be applied to the situation Evaluate each alternative by listing its advantages and disadvantages ( This may include consistency with company mission or strategy , long-term implications , resources available or impediments ) Identify the recommended solution along with any further justification Develop a recommended course of action if needed Case Study Methods Individual Group or Collaborative Brainstorming Role Playing SAMPLE CASE STUDY The Classification Conundrum Logistics and Customer Scheduling Introduction Scheduling is the matching of orders (or customer demand) against the capacity of the transformation system, and the reconciliation of conflicts between these orders for available capacity. For scheduling to be successful, there must be a measure of what capacity is available (and in reserve), and the effect of the orders in terms of their consumption of capacity resource. Introduction The presence of the customer in a service situation, and the ability of manufacturing to insulate itself from the customer by the use of stock, presents us with very different problems in terms of scheduling within each of the two sectors. For that reason, it is better to deal with each separately. Scheduling in Manufacture Aggregate Scheduling Manufacturing requires a planning horizon of reasonable length to ensure that core operations are protected from the day-today turbulence of the order book, as operations cannot be turned on and off like a tap. Typically, a rolling demand forecast for the next 12-month period is used to construct an aggregate schedule, which as the term suggests is a broad-brush approach to the problem. Aggregate Scheduling The month-by-month forecast demand for various product groups (appliances), rather than individual products (washers, dryers, dishwashers), impacts on aggregate capacity (workers and processes) over the required time-frame. Constraints need to be identified at a stage when adjustments can be made on a costeffective basis. For instance, the effect of resource trade-offs, holding stocks, working overtime or subcontracting can be identified at this stage. The output of the aggregate scheduling process is the production plan. Production Planning The production plan examines the capacity/demand situation in more detail, de-segregating the demands and the resource capacity, so that the effect of the product mix can be determined. At this stage there is a feasible balance between forecast demand and capacity. Constraints have been identified, and adjustments made, either, to demand or to capacity, ensuring compatibility. Master Production Scheduling At this point actual orders are incorporated into the scheduling system, and quantities set against specific end items for particular time periods. The Master Production Scheduling (MPS) acts as senior management’s handle on the business. By altering the MPS, product mix, and inventory levels, capacity demands can all be changed. Any attempts to squeeze more production out of the system may be counterproductive, as it could seize, if capacity constraints are exceeded. Master Production Scheduling The MPS will be used in conjunction with Requirements of Materials (ROM) to explode the component requirements implied by end item requirements. It is at this point that actual component requirements are calculated, aggregating additional requirements for spare parts and scrap. Master Production Scheduling At some point, typically after one month, the MPS is frozen, no more changes are allowed, since critical components (usually those with a long lead-time) will already have been obtained. It is at this point that detailed manufacturing scheduling takes place, when the schedule, job by job is loaded on capacity. Scheduling Approaches Forward Scheduling Forward Scheduling, occurs when production activities commences as soon as the order is received. Material and production capacities are allocated to the order on its arrival. This is typical of jobbing-shop operations where custom-made products are the norm, and the customer will not (or cannot) give advance notice of his requirements. Backward Scheduling Backward Scheduling, occurs when production activities are scheduled by their due-dates, working backward from the dates of end item requirement by progressively offsetting lead times to derive a schedule for the acquisition of materials and components. This situation is rather more typical of manufacture. Scheduling Activities We know the recipe for the product bill of material (BOM). We know the routes from process to process for the individual components (route cards). We now have to load these jobs into the various processes in a logical and efficient manner, ensuring that capacity constraints are respected and that required output levels will be achieved. Scheduling Activities This means that the order in which jobs will be processed (sequenced) will have to be determined, using prioritising rules, examples of which are given below: First Come-First Served Jobs are processed in strict order sequence Earliest Due Date Priority is given to jobs required soonest Longest Processing Time Jobs with longest processing time are assumed to have maximum added value Shortest Processing Time Priority is given to maximising flow of jobs Critical Ratio Method Priority is given to jobs where the ratios of time until due date against total process time is smallest Optimised Production Technology (OPT) An MRP based scheduling system assumes for instance that lead times for parts acquisition and builds are fixed, and that capacity is not a constraint, which can lead to problems. Just-in-time (JIT) too has its problems in maintaining an appropriate balance between resource utilisation and the flexibility that a very short planning horizon implies. Optimised Production Technology (OPT) The Optimised Production Technology (OPT) approach recognised the real work limitations on production resources and incorporated them as production constraints to schedules in the future. It recognises that lead times are not fixed, that capacity is finite, and that unlike JIT, sometimes it can be beneficial to increase batch sizes. The OPT system is a computer-based simulation that allows managers to ask the “what if” questions in addressing the problem of developing a feasible and acceptable schedule. Optimised Production Technology (OPT) It forms the basis of an approach (sometimes known as constraint management) that focuses management’s attention on the effective scheduling of bottleneck resources, as time lost on these cannot be recouped elsewhere in the production sequence. Input-Output Control One planning technique that helps control the flow of production activity at the shop floor level of control is input-output control. This approach seeks to monitor the planned versus actual output of work centres on a cumulative basis. What it does is to highlight discrepancies between theoretical and actual capacity, and should ensure that particular processes are not being overloaded. Gantt Charting The Gantt chart is one of the simplest (and most effective) scheduling tools available. It has a time-based horizontal axis, with work centres shown on the vertical axis. Set-up and process times for jobs can be shown as colour coded bars of lengths proportional to the time taken against the centres in question. Lead times and bottlenecks become readily apparent using this simple visual approach. Scheduling in Job Operations The custom and low-volume nature of job orders results in considerable variation in materials used, order processing, work-inprogress (WIP), capacity planning and setup time requirements. Much of management’s tactical objectives in scheduling focus on, efficiently, eliminating variation in production factors. Scheduling methods used in these types of operations include Gantt charts, job sequencing methods, critical ration and input-output control. Scheduling in Repetitive Operations The high volume and continuous nature of repetitive operations results in the need to closely control the flow of materials and application of labour resources to maximise flow and worker utilisation. Much of management’s scheduling effort is focused on attempting to synchronise demand with production activity. Scheduling methods similar to those used in jobbing can be used, but it is more likely that push-based MRP or pull-based JIT systems will be employed. THE PROJECT Project Subjects Onur Afacan Electronic Equipment Berkin Altın Automotive Spare Parts Burak Bilgili Furniture Anıl Çamdereli Edible Oils Pınar Karatop Fish Products Sıla Kasalı Milk Products Oya Ertuğrul Organic Children’s Wear Name of the Project “A Supply Chain Story from Production to Customer” How To Prepare The Project ? Make a research for the product and the market You have to establish a company Start from Manufacture till Delivery of the goods to target market . You can use the library or Internet You have to pay visits to companies to get information . But don’t forget ; it is not a “copy & paste” project You must input vision and try to make something interesting and different . You must like and admire what you have done . Prepare your project in ppt and present it to me on a flash memory . Also present a file of your ppt . You can add extra film or music or speech to your ppt . The minimum number of slides will be 30 and for the above you are free , no limit . Mention your references at the end of the ppt . What do we expect from the project ? You will establish a company Give details about your company Give details about the product Tell me about your market and how you are going to sell to that market Give details about the distribution channel(s) Tell me about the logistics operations Scheduling in Services Scheduling in Services The key issue in scheduling of services is the feasibility of encouraging the customer to give advance notice of his intention to use a particular service. This will clearly depend on the substitutability of the service and the degree of importance that the customer attaches to the service and to having it provided at a particular time. Appointment Systems Appointment systems are intended to control or alter the timing of customer arrivals (customer demand). The purpose of an appointment system is to maximise the utilisation of the limited time a service facility (or person) can be used, and minimise the inconvenience to the customer in terms of time spent waiting. An appointment system does not guarantee that the customer will not have to wait. Providers of specialist services, for example music teachers, may be fully booked for months in advance. Appointment Systems Appointment systems are ideal in non-emergency service situations; in periods of emergency, an appointment system usually breaks down. For instance, a consultant called away to deal with a crisis, will undoubtedly fail to meet appointments scheduled for the relevant period. Organisations using appointment systems and facing the occasional emergency usually build slack time into the schedule, which acts in the same way as buffer inventory in a manufacturing context in ironing out unexpected demands. Appointment Systems The schedule will normally consist of a list of names of customers requiring the service, with allocated time-slots and perhaps some detail on the nature of the service to be performed. Reservation Systems While reservation systems are generally used to schedule an organisation’s resources to meet an individual’s demand requirement, reservation systems are concerned with scheduling facilities and multiple resources to meet customer demand. For example, a hotel represents the multiple resources of bedrooms, leisure facilities, restaurant, etc. We do not make reservations with each of the resource providers in turn, but expect our requirements to be co-ordinated centrally. Reservation Systems Where a resource is particularly expensive to provide, for instance an aircraft, it is important to ensure that it is operated at as near maximum capacity as possible. Airlines bedevilled with the problem of no shows (intending passengers who do not turn up), may indulge in the practice of overbooking, where, for instance, 355 reservations may be accepted for an aircraft with only 350 seats. Reservation Systems Provided the airline has a good understanding of the probability distribution governing the likelihood of all the customers turning up, they can strike what they would regard as an effective balance between keeping their planes adequately loaded, and occasionally having to placate disappointed passengers. Whether this is ethical is another matter entirely, but no doubt the airlines would defend themselves by saying that without this practice, fares would have to rise. Forecast-based Systems Where the customer is not able, or willing, to give advance notice of his intention to consume a service, we are thrown back on the requirement to schedule the availability of capacity on forecast. Key planning information for the electricity generators would be the weather forecast, and the TV schedules, particularly party political broadcasts! Base load is met from relatively efficient thermal stations, with demand peaks supplied by (expensive) gas turbine, or (limited supply) hydropower. Forecast-based Systems While hospital Accident and Emergency departments may not formally undertake forecasting, the patterning of demand throughout the week is well understood. Since they are at their busiest on weekend nights, they would schedule extra resources to meet these anticipated demand peaks. Extra capacity would additionally be available on standby. Modelling Approaches to Scheduling In situations where appointment or reservation systems are inappropriate, it is important to collect data on customer demand patterns so that probability distributions can be constructed. The effect of service level choice on capacity can be readily determined. Modelling Approaches to Scheduling For example, knowing the distribution of evening demand by patients for community nurses, we can calculate that with ‘x’ nurses, we will require extra capacity on average one night in a hundred. With ‘x+1’ nurses, the extra capacity requirement might drop to one night in three hundred. The manager is then in a position to make a rational choice in terms of capacity and scheduling alternatives. Simulation An extension of the above approach enables us to construct (computer-based) models of dynamic service (and manufacturing) situations using the technique of Monte-Carlo simulation. The variation in customer arrivals, in service provision times can be readily represented as a dynamic graphic image on the computer screen, so that alternative strategies to managing the customer queuing, resource utilisation dilemma, can be explored quickly, and without disturbing an existing operational set-up. Materials Management in Services Introduction Facilitating goods play a vital role in the provision of services. It follows therefore that the provision of these goods in terms of quantities and timing needs to be carefully managed to strike a calculated balance between the problems of over provision and stock-out of materials, particularly where limited shelflives are involved. Perishables in Service Inventories Life of Items Very short Short Medium Long Items Concert tickets, transplant organs Fruit, meat, dairy products, commemorative items (jubilee mugs) Certain vaccines, seasonal clothing Books, postage stamps, hardware Role of Inventory Inventory is held in anticipation of known demand, where it is said to be dependent, and to buffer the service system against unexpected peaks, where an independent demand regime is operating. Inventory also has to protect the system during the time when stocks are being replenished. Intuitively you will recognise that where a replenishment system is fast and responsive, with a short lead-time, less protection is required, and therefore safety checks can be correspondingly lower than in situation where lead-times are greater. Lumpiness of Input Materials in Services Lumpiness Smooth Items Provision of central heating oil Minor lumpiness Office supplies, paint Moderate lumpiness Timber cut to order, floor coverings Major lumpiness Clothing, cosmetics, printing to special order Inventory Control Systems for Independent Demand Items Fixed Quantity System A fixed quantity system adds the same amount to the item’s inventory each time it is ordered. Orders are placed when the stock level drops to a critical level called the reorder point. Each time an item is withdrawn from stock, the amount of inventory on hand should be compared with the reorder level, and only when it has reached that level is an order for replenishment (of a fixed quantity) triggered. Fixed Quantity System Where a fixed order size is desirable, perhaps because of quantity discounts, or where material has to be delivered in certain quantities, by the lorry load or in pallets, this method of controlling stocks can have certain advantages. It should be noted that the period of uncertainty which safety stock has to provide protection for only extends to the lead-time for replenishment. Fixed Period System In a fixed period system, the decision to replenish is time triggered, rather than event triggered, as described above. On-hand inventories are only checked when the reorder period is due, and only the amount of material to bring the stocks up to some predetermined maximum level is ordered. Fixed Period System The main advantage of this system is the elimination of the requirement to count and recount stock after each inventory transaction. For ease of administration, it also provides blocks of orders, on a weekly, monthly or quarterly basis to be generated for processing. Inventory Planning The Economic Order Quantity Model (EOQ) There are costs associated with the holding of inventory, capital tie-up, spoilage, provision of storage, etc. There are also costs associated with the placement and receipt of orders, the raising of paperwork, transportation and handling of materials. It follows that if we place orders for modest quantities frequently our ordering costs will be relatively low. What we have here is a classic operations trade-off. It can be shown that the costs of operating the system are minimised when: The Economic Order Quantity Model (EOQ) Q* = Where: 2DS H Q* is the Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) D is the period demand rate S is the costs of placing a single order H is the unit holding costs per period Calculation for Economic Order Quantity The Economic Order Quantity Model (EOQ) The EOQ approach may have some validity in service sector applications, where basic consumables are concerned, and shelf life is not an issue. It has however been vigorously criticised by Professor John Burbridge, among others in that it regards costs as a given, and does not seek strategies for their reduction, permitting more frequent ordering, and lower stock holding costs. Requirement Planning for Dependent Demand We may tend to regard the Bill of Materials as a concept with application only in the manufacturing sector. End-use items are exploded, layer by layer into their constituent sub-assemblies, components and materials to create an overall recipe for the product. The term recipe Is quite an apt one, as in cooking we have to ratio the quantities required for a given dish according to the number of guests. The quantities are dependent on the number of end-times. Requirement Planning for Dependent Demand The BOM approach is used in mass catering, for instance, in the provision of airline food, and also in hospitals. A particular health authority in the UK was having a problem, controlling inventory in its hospitals. Lots of unofficial stocks were being squirreled away, on a just-in-case basis, giving the culprits the security of their own supplies, without any control from central stores. This had several effects. Stocks had to be generally higher to give a particular level of protection, as each unofficial store was only protecting its own area. Requirement Planning for Dependent Demand Some of the items were shelf life dependent, and as a result, unused stocks had to be scrapped on date expiry. Now, a more rigid central stores system has been introduced. For example the theatre operations programme, with its master schedule (feasible for elective surgery), drives the provision of kits of material for particular procedures (dressings, sutures, etc). The authority claims a dramatic reduction in stock holdings, with service levels in no way impaired or compromised. Supply Chain Management Purchasing Introduction Raw materials and bought-in components typically account for 60%-70% of the final cost of manufactured goods. Indeed in some sectors, for instance the manufacture of personal computers, this figure can be as high as 95%. If we include the cost of services that support manufacturing operations, this figure can be pushed even higher. The search for competitive advantage focuses on the main cost burden. Introduction Current thinking shows that the most effective way to reduce that burden is to improve the value received for purchasing expenditures (thus lowering total costs) by having better suppliers. This means that much more attention is being placed on the purchasing function and its related activities. Introduction Service organisations are beginning to realise the strategic implications of securing more effective management of their purchasing activities. Government bodies, local authorities, hospital trusts, and private sector service firms seek highquality suppliers. The buyer, working in isolation, leafing through catalogues, searching for the best price deal, is increasingly being supplanted by teams of purchasing professionals, throughout the organisation, working towards quality-oriented partnership arrangements with a handful of preferred suppliers. The Changing Role of Purchasing Traditionally, purchasing has tended to be regarded as a low-level, mundane activity, heavily routinised, and not offering much in the way of intellectual challenge. That attitude, and its accompanying practices survived the upheaval brought about by the introduction of tighter material planning systems made possible by the introduction of computing, such as MRP. The Changing Role of Purchasing The second phase, featuring Just in Time and Total Quality has necessitated a complete rethink on the appropriateness of traditional purchasing practices that involved centralised purchasing departments and commodity specialisation; for instance one buyer being responsible for purchase of electronics, another for paper. Fielding enquiries, dealing with problems of late delivery, wrong quantities or items, poor quality had led to a fire-fighting mentality and prevented purchasers from getting to know their suppliers properly. The Changing Role of Purchasing The alternative is to create broad teams focused on products or customers, including in their membership engineers, marketers, and quality specialists for example, and having a much broader remit than just material/service acquisition, but encompassing all phases of the product or service, from design to eventual supply. Supplier Partnerships Traditionally, buyers bought primarily on price, with quality and delivery being of secondary importance, and a supplier of many years standing could find himself dropped if a rival bidder was able to offer more attractive terms. Buying companies distrusted their suppliers, a feeling that was heartily reciprocated by the suppliers, with the result that they did not always do their best for their customers, making their replacement by other suppliers more likely. Supplier Partnerships There is now a trend away from the detached, adversarial relationships that characterised the ‘70’s and much of the ‘80’s, with large industrial organisations and major retailers, for example, General Motors, Marks and Spencer’s leading the way. The following table makes this point. Value-based Purchasing In a value-chain system, each link must add value. This concept can be used in many different contexts. For example, the following diagram (Figure 5) shows the complete cycle form extraction from the earth to return to the earth for a manufactured product. Value-based Purchasing The value chain applied to an organisation represents the organisation as a series of links in a chain. The firm is in the centre with its internal links. Upstream links involve the firm’s suppliers, whilst the firm’s customers lie downstream. Value chain management identifies the interactions between each link in the chain, and the role of the links in improving value. When applied to purchasing, the value chain concept attempts to create value through purchasing decisions, rather than concentrating on cost savings through vendor selection and contract negotiations. Value-based Purchasing Value may be added by: improving product quality speeding up the response between the links better sourcing improving inventory control using higher quality materials. Value-based Purchasing The Life-Cycle-Cost Model fits quite comfortably with this concept, whereby the cost of ownership (or at least involvement with a product or service) is not necessarily minimised by squeezing acquisition costs down to the bare minimum. The phrase ‘buy cheap – buy dear’ applies! Supply Chain Management At one time, the key to a strategic advantage and clout in the marketplace lay in controlling the, largest resource base, manufacturing plants and research facilities. In today’s marketplace, this is no longer sufficient to enable a company to sustain its position. As IBM has discovered, competitors can clone IBM’s most successful product, the PC. They have bypassed and even surpassed the best that IBM can offer. Supply Chain Management Instead, maintainable, superior competitive advantage is not simply product-based but lies in, the effective design and control of the chain of events, beginning with the sourcing of raw materials and components and ending with the delivery of the completed product (or service) to the customer. It is possible for firms to add value and achieve sustainable differentiation from the competition, because competitors may find it more difficult to acquire the in-depth know-how required to manage logistics effectively. Supply Chain Management Logistics provided the key competitive advantage at Seagate Technology, a leading manufacturer of PC hard disc drives. In an effort to secure that lead, particularly in Japan, Seagate decided to absorb the cost of delivering its product to customers, and guaranteed delivery within four days. Supply Chain Management Because the delivery guarantee was an essential component of the package, Seagate developed an alliance with an air freight company to make deliveries from Seagate’s Californian distribution centre to customers all over the USA. Significantly, this initiative, so attractive to its customers, only added 1% to the unit cost of each disc drive. Seagate’s proportion of late deliveries was also less than 1%. Supply Chain Management In today’s saturated markets, customers demand greater flexibility and faster reaction from their suppliers. Terms such as quick response logistics and turbo logistics systems are becoming increasingly common in business literature. Essentially, the competition is compelling companies to manage their material flows better, from vendors right through the pipeline to customers. QR Supply Chain Management Effectively managing the flow of materials through the logistics pipeline involves managing the sequence of all material flow activities from suppliers to customer that add value to the final product. Electronic Information Flow A supply chain links all stages, from raw material through production to the customer. While many systems (such as MRP) push the product out to the user, others pull it through (such as JIT or Kanban based systems) where the product is produced only when needed. In all cases, however, the frequency and speed of communicating information has a marked effect on, inventory levels, efficiencies and costs, as the uncertainties due to time-lags in information provision are reduced. Electronic Information Flow Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) used by banks and supermarket chains is one area that is receiving much wider attention in the current competitive climate. Several systems have been developed and are discussed in more detail below: Quick Response (QR) programmes have grown rapidly. The approach is based on bar-code scanning and EDI. Its intent is to create a just-in-time replenishment system between vendors and retailers. Electronic Information Flow Efficient Consumer Response is a variation of QR and EDI adopted by the supermarket industry as a business strategy where distributors, suppliers, and retailers work closely together to bring products to consumers. It uses bar-code and EDI. Savings come from reduced supply chain costs and reduced inventory. A study by Kurt Salmon Associates estimates a potential reduction in supply chain dry-goods inventory from 104 days to 61. McKinsey suggests that prices could on average be reduced by almost 11% by wider adoption of ECR. Electronic Information Flow Without ECR, manufacturers, aided and abetted by the supermarkets, push products onto customers where special offers and promotional techniques are employed. Unsold products go back into store until the next big push. ECR focuses on the customers to drive the system, not the deals offered by the suppliers. Customers pull goods through the pipeline by their purchases, thus reducing the inventory throughout the system. One study suggests that distributors purchase 80% of their merchandise during manufacturers’ sales. Until the industry frees itself from this addiction to deal buying, all the great replenishment approaches will be worthless. THANK YOU