Arabic varieties and LADO IAFL 2011 final

advertisement

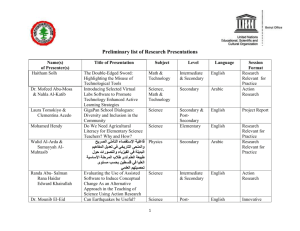

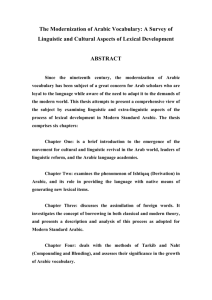

LADO colloquium at IAFL conference, 11-14.7.2011 Aston University, Birmingham, UK Arabic varieties and LADO: How can LADO deal with variance? Judith Rosenhouse SWANTECH Ltd. swantech@013.net.il 1. Introduction The title of this talk indicates that we deal here with LADO problems, with Arabic as a “case study.” We will not discuss here whether using linguistic methods for this goal is justified or not. Our talk has three major parts: 1. Background: The Arabic language 2. The problems of LADO with reference to Arabic 3. Suggesting some solutions to the problems. and: Conclusion References 2 1. Introduction to Arabic Figure 1. Main Arabic dialect regions (ArabAtlas) 3 1. Introduction to Arabic Arabic has been expanding out of its original region, the Arabian Peninsula, since the 7th century CE Native speakers of Arabic are found now, mainly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). “Fringe” dialects of Arabic are spoken in Central Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Due to recent migrations many Arabic-speaking communities exist in the other continents. (cf. Holes 2004; Kaye & Rosenhouse 1997; Rosenhouse 2009) Arabic now is 5th/6th world language by number of speakers (> 250 million native speakers). 4 1. Introduction to Arabic Arabic has two basic registers: a rich, prestigious, written Literary (LA) form and spoken (CA) dialects: CA LA spoken, colloquial written, literary vernacular dialects modern standard This dichotomy is diglossia (Ferguson, 1959) which is an inherent part of Arabic 5 1. Introduction to Arabic In this diglossia state: CA is the speakers’ mother tongue LA is studied at school and is not a mother tongue. CA varieties differ among themselves and from LA on all linguistic domains at various rates (depending on the dialect) 6 1. Introduction to Arabic CA dialects are first classified geographically into Eastern and Western dialects. These are classified into sedentary urban (towns) and rural (villages), and nomadic tribal dialects. [Along history, including the 20th century, many nomadic dialects changed due to sedentarization.] 7 1. Introduction to Arabic Five main factors affect Arabic and its varieties: Geography, Social status, Religion, Sex, Education. Education is particularly relevant for diglossia: Speakers’ proficiency in LA and daily communication in CA is affected by Education (cf. Al-Wer, 2002). Note that CA simultaneously affects LA 8 1. Introduction to Arabic Political and cultural changes occurred in the 20th century due to: strong Western influence on the MENA, technological progress, and general globalization processes. Arab immigrants and refugees immigrated to other Arabic-speaking countries and to non-Arabic-speaking countries in other continents. There they form contacts with different Arabic varieties and other languages. 9 2. LADO problems Immigrants’ contacts with new language communities usually yield language processes such as: borrowing, code switching / code mixing, erring, linguistic accommodation, mother tongue attrition… These processes can be found also in the speech of Arab immigrants, many of whom are LADO clients. 10 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Concerning LA/CA relations: Shraybom-Shivtiel(1995) writes as follows: “The phenomenon of the renaissance of the Arabic language must not be construed in the sense of the death and subsequent revival of the language…but rather as the penetration of a language which has previously existed in written form exclusively into widespread areas of everyday social communication.” She also shows there CA effects on the Egyptian Language Academy. 11 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching LA/CA relations in Egypt, are described, e.g. in: ‘Egyptian Arabic as a Written Language’ (Rosenbaum, 2000) ‘Do you parler ‘Arabi?” Mixing Colloquial Arabic and European Languages in Egyptian literature’ (Rosenbaum, 2000-2002) 12 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Rosenbaum (2000) begins with these words: “The change of attitude in Egyptian culture toward the colloquial and the change of stylistic norms in the literary system have encouraged the appearance of various kinds of mixed styles, not only in oral performance but in written texts as well.” These mixed forms are in fact Code Switching (CS) 13 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching The following example is from a play using CA, LA, German and English (Rosenbaum, 2000-2002: 24) 14 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching CS is revealed also with other languages and dialects. See, e.g., the case of Morocco and the relationship between Moroccan Arabic and French (Lahlou, 1991: 182-183, in Caubet, 2000): “Code switching has become part of their linguistic repertoire….the use of CS by these people is not an indication that they have not mastered the languages among which they switch. It is a linguistic behavior that indicates a choice… 15 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching “It is true that many code switchers find it easier to use CS than to use either Moroccan Arabic only or French only. But this is because CS has become their usual everyday means of interaction with their peers. CS is their ‘default mode’ of conversation, a mode which is in the middle of their linguistic continuum…” (Lahlou, ibid.) 16 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching These examples demonstrate fundamental changes in Arabic in the 20th century due to literacy and language contacts (among other factors). (Needles to say, there are many other examples.) Thus, CA and LA keep developing and changing naturally - like any other living language. 17 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Three types of CS can be mixed in their speech: • Intra-lingual Diglossic switching (CA-LA). • Inter-lingual Code switching • Inter-dialect Variety switching (dialects) Psycholinguistically these processes are similar, for many speakers switch between these varieties or languages even without noticing it, as a life habit. (on Arabic, see also: Mejdell, 2006) 18 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching For LADO these natural processes increase the problems involved in verifying speakers’ origin by their language use. The very concept of LADO and its tasks raises many questions (Muysken et al. 2010: 2-4). For us, a crucial question is: How can an expert be sure that a given person is a native speaker of a certain Arabic dialect (or not), if that person’s recorded speech is not pure or typical of the claimed dialect when it presents certain features of different dialects, or lacks specific or characteristic dialect forms? 19 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching We’ll examine this problem by three questions: 1) Which is the speaker’s original dialect out of several dialectal features found in a recorded text? (2) How does one decide which feature is more salient (significant) than others when several dialects are involved? (3) Should only what is in the recorded texts be considered in deciding the speaker’s original dialect or also what is not expressed verbally? 20 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Q1. To decide a speaker’s original dialect at least three optional approaches may be tried: 1. Counting the number of all the features of each dialect in the text and deciding by the majority; 2. Assessing the saliency of different dialect features, counting them and deciding by the majority of the salient features; 3. Combining these methods. The 3rd option is probably the preferable. These methods can be used in all the switching types 21 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching However, one may argue that these methods may refer to dialect dominance in the recording rather than speaker’s origin (in case speakers want to imitate some dialect other than their original one). It seems, then, that these method do not provide a foolproof answer for Q1... 22 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Q. 2 is about feature salience: How does one decide which feature is salient when features of several dialects occur in the recording? Note that: A feature may be salient for some dialect but not for another. A feature that is common to several dialects is hardly salient as a distinctive marker. 23 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching This issue leads to considering geographical dialectology which studies different dialects and their borders (Behnstedt, 2006, Belinkov, 2010) Dialect atlases and isoglosses might be used. But in spite of the great progress in this area (Behnstedt and Woidich, 2005), Arabic dialects are hardly documented or covered in such maps. Vocabulary is one of the linguistic areas used to mark inter-dialect differences (cf. Cadora, 1979, for Arabic following Swadesh, 1971). Let’s examine this aspect now. 24 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Cadora (1979: 32) found that dialects in the SyroLebanese varieties revealed 96% non-contrastive compatibility on the average (i.e. cognate lexical items). This fact complicates things for LADO: As vocabulary is that similar (at least in these dialects), it is not too difficult for a speaker of a certain dialect to master the vocabulary of a different dialect. 25 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching Quoting Swadesh (1952a, b) Cadora also suggests the minimum 70% requirement of noncontrastive compatibility for dialects to be still considered varieties of the same language - in this context of Arabic dialects. This is a rather broad lee-way for inter-dialect differences, and is probably not satisfactory for LADO needs. 26 3. Some CA problems for LADO: diglossia, Code and Variety Switching So, to answer Q 2 linguists would usually examine features of syntax, morphology, phonology and vocabulary (in this order) in the recording, because: Syntax and Morphology are considered the core of a language system as they are the last to be affected by external linguistic forces, while Phonology and Vocabulary are the weaker parts of a language system and can change easily (diachronically and synchronically). These considerations are relevant for Arabic, too. Here are some examples: 27 4. Results of processes in CA Examples of syntactic distinctive features: Copula at the end of the phrase: Baghdad: -ya:nu; Anatolia: -we (others: simple 3rd person pron.) Bound personal particle preceding the direct object: Iraq: šufto la-mHammad ‘I saw M.’ the possessive structure: Iraq: be:to la-mHammad ‘M.’s house’ Imperfect indicative particles Damascus: bi; Iraq: qa; Morocco: da, ka Genitival exponents Iraq ma:l; Syria: taba‘; Cairo: bita:‘; Galilee Bedouin: Hagg; Morocco: nta‘, dyal; Malta: tagH, tiegH Noun-negating particles Baghdad: ma: Damascus: mu: Cairo: muš Jerusalem: muš, miš 28 4. Results of processes in CA Examples of morphological distinctive features: Pronouns: “I”: Cairo, Damascus: ana; Yemen, Bedouins: ani/a:ni Bound (suffixed) pronouns: “his”: Cairo: -uh; Damascus: -o; Bedouins: -ih/ah/uh; Morocco: -u/-eh Verb conjugations, Perfect tense: “I wrote” Cairo, Damascus: katabt; some in Yemen: katabk; Morocco: ktebt Morphophonology: ima:la (=/a>e, i/ in certain word patterns): Cairo: no ima:la; Damascus: conditioned Iraq, Malta: much 29 4. Results of processes in CA Examples of dialect-distinctive phonological elements Feature urban Eastern vs. urban Western Consonants */q/ ’ q often retained Diphthongs /ai, au/ retained often ai>i/a, au>u Long/short vowels retained often long >short; short>null Feature Urban vs. Nomadic (Bedouin) Consonants q; k; g; ’ g/dž/dz; k/tš/ts; dy t, d, δ θ, δ, δ Pharyngealized few, weakened many, strong Feature Muslim Baghdadi Christian Baghdadi Bedouin type sedentary type Consonants g/dž, k/tš, đ vs. q, k, Ima:la* little vs. */a/>/e~i/ in certain word patterns much 30 4. Results of processes in CA Vocabulary: Fig. 2. Semantic field of the verb “to speak” (Behnstedt & Woidich, 2005:209): 3 main centers + other forms 31 4. Results of processes in CA • To answer Q 2 it seems that a meticulous examination of all these aspects in the speaker’s recording should be undertaken. • Due to inter-dialect similarities by geographical regions when features are mixed it would be difficult to reach a clear-cut opinion. This is true in particular if the speech features in the recording are of the shared rather than the distinct character. • So, to answer Q2 a comprehensive study of the salient features of the Arabic dialects is necessary. Until then the answer to Q2 is also pending. 32 4. Results of processes in CA Our Q3 is rather “philosophical”: Should one define a speaker’s original dialect only by what is in the recorded texts or also by what is not shown? Speakers may try to disguise their “original” features, and hide some weakness by avoidance strategies (e.g. Milroy, 2002). Conversely, they may also try to reveal closeness to the interlocutors (or some dialect) by imitating the interlocutor’s features which are “foreign” for the speaker. 33 4. Results of processes in CA Concerning Arabic, inter-dialectal communication phenomena were described as: Leveling of conspicuous dialectal features, and Koineization: use of features shared by the speakers, thus hiding differences between them. (Blanc, 1960). Such behavior has also been described as speakers’ sociolinguistic accommodation due to factors such as status, sex, or origin. 34 4. Results of processes in CA If the non-appearance of some features is known – how can it be considered? Or: Is it a fact to be considered at all? In the context of LADO speakers, these phenomena are frequent. All the facts described above reveal a complex picture, which is important to take into consideration. Our questions will remain unanswered for now, but we tend to support an approach that somehow takes into consideration “missing forms”. 35 5. Suggestion for LADO: A Linguistic Template At least as a partial answer or aid, a good computer program could treat at least some of these aspects. In contrast with speaker and speech recognition, not much effort has been dedicated to designing and using computer programs for LADO goals. (but see a review in Belinkov, 2010). As a first step towards the use of computer programs in LADO, it seems necessary to define general linguistic protocols as templates for different dialect features. 36 5. Suggestion for LADO: A Linguistic Template To reach a relatively reliable evaluation of a recorded text, two combined parts seem to be necessary: (1) A feature array (database) of as many Arabic dialects as possible (including LA) (2) A computer program which calculates the probabilities of origin by features and feature combinations Cadora’s 70% rate could be considered the lowest base-line for some probability that a speaker is right in claiming a specific dialect as L1, but higher certainty rates are better, of course. (In computerized speech analysis/synthesis programs good rates are around the 90%-95% success.) 37 5. Suggestions for LADO: A Linguistic Template For stage (1) the lists need to include at least: 1. The basic features which are common to all the Arabic dialects 2. A list of distinctive features of Arabic dialects (The features will have to refer to all language forms.) For stage (2) the program will be able to register the data, classify and list the features by dialects, and calculate the probability that a group of n features reflects a certain dialect. This approach should be further developed. 38 5. Suggestions for LADO: A Linguistic Template It may be possible to reach a reliable result only if the salient features are defined as well as the features involved in speech accommodation. Such a project requires much work and time, but seems feasible at least for several dialects due to the present programming and memory capacities. Yet, even if this project materializes (for a few dialects), it still does not enable 100% certainty - at least because: Not all the Arabic dialects are known/documented (Behnstedt, 2006) and probably cannot be documented. 39 5. Suggestions for LADO: A Linguistic Template In the context of Q. 3, we suggest that dialect-typical features that do not appear in the recordings (where they could occur) will be taken into account as a negative factor for origin assessment. This is a difficult task, for the pragmatic use of certain features (such as sociolinguistic accommodation) involves behavior patterns that are not strictly defined (as in computerized calculation) and some freedom is normally possible in human speech. 40 6. Conclusion In sum: Arabic has numerous dialects/varieties. Their variance exists not only due to number but also due to their sometimes unexpected mixtures. Changes are undergoing in Arabic varieties, in both Arabic-speaking countries and elsewhere, due to internal and external processes. A person’s speech reveals these changes at least by code switching, borrowing, leveling & koineization, which depend on the speaker’s personal language make-up. These natural processes complicate LADO work. 41 6. Conclusion In order (at least) to facilitate LADO, we suggested the design of a computer program with two parts: Level 1: A linguistic analysis of Arabic dialects’ features as the data base (for the second part). Level 2: A computational analysis that will run the probability calculation for any recording to examine whether a certain text reflects one dialect (rather than another) as an L1. This design is influenced by the existing literature (e.g. Rose’s (2002) approach to speaker identification). 42 6. Conclusion Though calculated (statistical) probability is not 100% certainty, it may support impressionistic “gut feeling” or extra-linguistic and semi-scientific opinion about the origin of a text. A computerized program such as suggested here requires much work, but seems feasible in stages, at least for some dialects. Collaboration of teams of linguists, programmers and statisticians is needed to materialize this project. The final “human touch” is nevertheless inevitable in this task (as in many others), but such a program may contribute to solving some of the LADO language variance problems. 43 The End Thank you for your attention 44 References Al-Wer, E. (2002) Education as a speaker variable. In: Rouchdy, A. (ed.) Language contact and Language Conflict in Arabic: Variation on a sociolinguistic theme, London: RoutledgeCurzon, 41-53. Behnstedt, P. and M. Woidich (2005) Arabische Dialektgeographie. Eine Einführung, Leiden: Brill. Behnstedt, P. (2006) Dialect Geography. In: K. Versteegh et al. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill, Vol. 1, pp. 583-593. Belinkov, Y. (2010) Computational dialectology, NLP Seminar, January 2010, TelAviv University Blanc, H. (1960) Style variations in spoken Arabic. In: C.A. Ferguson (ed.) Contributions to Arabic Linguistics, MA. 81-158. Cadora, F.J. (1979) Interdialectal Lexical Compatibility in Arabic: An Analytical Study of the Lexical Relationships among the Major Syro-Lebanese varieties, Leiden: Brill Holes, Clive. 2004. Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions and Varieties, Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press. Kaye, Alan S. 1994. Formal vs. informal in Arabic: Diglossia, triglossia, tetraglossia etc., polyglossia - multiglossia viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift für arabische Linguistik, 27:47-66 Kaye, A.S. and J. Rosenhouse (1997) Arabic dialects and Maltese. In: R. Hetzron (ed.) The Semitic Languages, London: Routledge, 263-311. Mejdell, Gunvor. 2006. Code-switching. In: K. Versteegh et al. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill, Vol. 1, 415-421. 45 References Milroy, L. (2002) Introduction: Mobility, contact and language change – Working with contemporary speech communities, Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6: 3-15. Muysken, P., M. Verrips and K. Zwaan (2010) Introduction. In: K. Zwaan, M. Verrips and P. Muysken (eds. ) Language and Origin - The role of Language in European Asylum procedures: Linguistic and Legal Perspectives, Nijmegen: Wolf legal Publishers, 1-6. Rose, Ph. (2002) Forensic Speaker Identification, London: Taylor & Francis Rosenbaum, G.M. (2000) ‘ “FusHāmmiyya”: Alternating style in Egyptian prose’, Zeitschift für Arabische Linguistik, 38:68-87. Rosenbaum, G.M. (2000-2002) “Do you parler ‘Arabi?” Mixing Colloquial arabic and European Languages in Egyptian literature, Materiaux Arabes et Sudarabiques-GELLAS, Nouvelle Serie, 10: 11-47. (Groupe d’Etudes de Linguistique et de Litterature Arabes et Sudarabiques) Rosenbaum, G. M. (2004) Egyptian Arabic as a Written Language, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, 29: 281-340 Rosenhouse, J. (2009) “Arabic in Comparative Forensic Linguistics,” paper presented in the 4th Conference on Translation, Interpretation and 46 Comparative Legi-Linguistics, 2-4.7.2009, Poznan, Poland. References Shraybom-Shivtiel, Sh. (1995) “The role of the colloquial in the renaissance of Standard Arabic,” Israel oriental Studies, 15: 207-215. Swadesh, M. (1952a) “Lexicostatistical dating of prehistoric ethnic contacts with special reference to North American Indians and Eskimos,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, XCVI: 452-463. Swadesh, M. (1952b) “Towards greater accuracy in lexicostatistics dating” IJAL, 28: 223-230. Swadesh, M.(1971) “What is glottochronology?” In Swadesh, M. (ed. by J. Sherzer) The Origin and Diversification of Language, Chicago/ New York: Aldine-Atherton, 271-284. Swadesh, M.(1971) “What is glottochronology?” In Swadesh, M. (ed. by J. Sherzer) The Origin and Diversification of Language, Chicago/ New York: Aldine-Atherton, 271-284. 47 Examples of Lexical Contamination (mixed forms) (Behnstedt & Woidich, 2005): Lebanon-Syria: iffe, burtum; bartu:me, burtme “lip” Egypt: furn (m); tabu:na (f); furne (f) “cooking oven” Syria: batti:x: watermelon (red); melon (yellow); either (neutral + adjective to qualify the meaning) To sum up this issue: Certain features distinguish different dialects, while others are common to many dialects. 48 Now, if A is the recorded text of a LADO client which claims a certain dialect, and B is the template structure of that dialect, then after adding up the features: 1. If the final feature score of (A) < (B), (A) is negated (= it is not considered the speaker’s L1). 2. 2. A (the claimed dialect) would “lose” also when it shows features of more than one dialect - depending on the salience of the features. This make its features more than (b)’s features, if the (a) features are more salient than any of the (b) features. 49