Value Chain And Purpose Of Business

advertisement

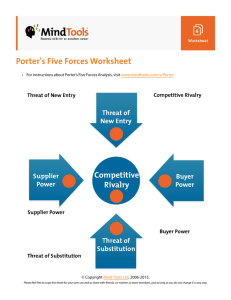

Value chain From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Contents [hide] 1 The Value Chain Model 2 When not to apply The Value Chain 3 Further Developments in Value Chain Research 4 References 5 See also 6 External links [edit] The Value Chain Model Popular Visualization The value chain, also known as value chain analysis, is a concept from business management that was first described and popularized by Michael Porter in his 1985 best-seller, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. It is important not to mix the concept of the value chain, with the costs occurring throughout the activities. A diamond cutter can be used as an example of the difference. The cutting activity may have a low cost, but the activity adds to much of the value of the end product, since a rough diamond is a lot less valuable than a cut diamond. The value chain categorizes the generic value-adding activities of an organization. The "primary activities" include: inbound logistics, operations (production), outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and services (maintenance). The "support activities" include: administrative infrastructure management, human resource management, R&D, and procurement. The costs and value drivers are identified for each value activity. The value chain framework quickly made its way to the forefront of management thought as a powerful analysis tool for strategic planning. Its ultimate goal is to maximize value creation while minimizing costs. The concept has been extended beyond individual organizations. It can apply to whole supply chains and distribution networks. The delivery of a mix of products and services to the end customer will mobilize different economic factors, each managing its own value chain. The industry wide synchronized interactions of those local value chains create an extended value chain, sometimes global in extent. Porter terms this larger interconnected system of value chains the "value system." A value system includes the value chains of a firm's supplier (and their suppliers all the way back), the firm itself, the firm distribution channels, and the firm's buyers (and presumably extended to the buyers of their products, and so on). Capturing the value generated along the chain is the new approach taken by many management strategists. For example, a manufacturer might require its parts suppliers to be located nearby its assembly plant to minimize the cost of transportation. By exploiting the upstream and downstream information flowing along the value chain, the firms may try to bypass the intermediaries creating new business models, or in other ways create improvements in its value system. The Supply-Chain Council, a global trade consortium in operation with over 700 member companies, governmental, academic, and consulting groups participating in the last 10 years, manages the de facto universal reference model for Supply Chain including Planning, Procurement, Manufacturing, Order Management, Logistics, Returns, and Retail; Product and Service Design including Design Planning, Research, Prototyping, Integration, Launch and Revision, and Sales including CRM, Service Support, Sales, and Contract Management which are congruent to the Porter framework. The "SCOR" framework has been adopted by hundreds of companies as well as national entities as a standard for business excellence, and the US DOD has adopted the newly-launched "DCOR" framework for product design as a standard to use for managing their development processes. In addition to process elements, these reference frameworks also maintain a vast database of standard process metrics aligned to the Porter model, as well as a large and constantly researched database of prescriptive universal best practices for process execution. A value chain reference model (VCOR) has been developed by the Value Chain Group to offer de facto standard for value chain management encompassing one unified reference framework representing the process domains of product development, customer relations and supply networks called the Value Chain Operations Reference model,or VCOR. VCOR is the next generation Business Process Management that extends the Supply Chain processes of Acquire, Build, Fulfill and Support to include Market, Research, Develop, Brand, Sell and Support. The three centers of excellence are product excellence, operations excellence, and customer excellence. [edit] When not to apply The Value Chain Porter's basic model describes an industrial organization buying raw materials and transforming these into physical products. In 1985, when Porter introduced the Value Chain, around 60% of most western economies' workforces were active in service industries. In 2006, most service industries in western countries employ over 80% of the workforce. Critique on the Value Chain model and its applicability to services organizations has since been voiced by both academics and practitioners. See for example (Peppard and Rylander, 2007) and (Van Middendorp, 2005). Porter's focus on 'either or' strategies and competition as the main driving force in any industry, are not that well suited to the complexity of most industries today. Collaboration in addition to competition and differentiation in addition to low cost are common drivers. Furthermore, Porter is focused on the tangible outcomes of cost, revenue, margin and basic configuration of business activities. The Value Network may be the mental model that embraces the linear Value Chain Model and that adds an extra dimension for those seeking to make sense of complexity as we see it in organizations and their environment today. [edit] Further Developments in Value Chain Research More recently, the term value grid has been developed to highlight the fact that competition in the value chain has been shifting away from the strict linear view defined by the traditional 'value chain' model (Pil and Holweg, 2006). The value chain in its original sense was defined as a sequence of valueenhancing activities. In its simplest form, raw materials are formed into components, which are assembled into final products, distributed, sold, and serviced. Frequently, the activities span multiple organizations. This orderly progression of activities allows managers to formulate profitable strategies and coordinate operations. However, it can also put a stranglehold on innovation at a time when the greatest opportunities for value creation (and the most significant threats to long-term survival) often originate outside the traditional, linear view. Traditional value chains may have worked well in landline telecommunications and automobile production during the last century, but today innovation comes in many shapes and sizes—and often unexpectedly. Pil and Holweg hence argue for seeing value creation as multidirectional rather than linear. Given the constant tension between opportunity and threat, firms need to explore opportunities for managing risks, gaining additional influence over customer demand, and generating new ways to create customer value. Nokia, for example, is legendary for having the foresight to lock in critical components that were in short supply, allowing it to achieve significant market share growth. However, a few years ago it suffered a setback when competitors used the same strategy to take advantage of shifts in the demand for LCD displays. Protection against such fickle reversals calls for a more complex view of value— one that is based on a grid as opposed to the traditional chain. The grid approach allows firms to move beyond immediately recognizable opportunities and across industry lines. This permits managers to identify where other companies— perhaps even those engaged in entirely different value chains—obtain value, line up critical resources, or influence customer demand. The new paths can be vertical; horizontal; and even diagonal. Successful managers need to learn how to assemble multi-faceted value grids that leverage new opportunities and respond to new threats. Porter generic strategies From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Michael Porter has described a category scheme consisting of three general types of strategies that are commonly used by businesses. These three generic strategies are defined along two dimensions: strategic scope and strategic strength. Strategic scope is a demand-side dimension (Porter was originally an engineer, then an economist before he specialized in strategy) and looks at the size and composition of the market you intend to target. Strategic strength is a supply-side dimension and looks at the strength or core competency of the firm. In particular he identified two competencies that he felt were most important: product differentiation and product cost (efficiency). He originally ranked each of the three dimensions (level of differentiation, relative product cost, and scope of target market) as either low, medium, or high, and juxtaposed them in a three dimensional matrix. That is, the category scheme was displayed as a 3 by 3 by 3 cube. But most of the 27 combinations were not viable. Porter's Generic Strategies page1 In his 1980 classic Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analysing Industries and Competitors, Porter simplifies the scheme by reducing it down to the three best strategies. They are cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation (or focus). Market segmentation is narrow in scope while both cost leadership and differentiation are relatively broad in market scope. Empirical research on the profit impact of marketing strategy indicated that firms with a high market share were often quite profitable, but so were many firms with low market share. The least profitable firms were those with moderate market share. This was sometimes referred to as the hole in the middle problem. Porter’s explanation of this is that firms with high market share were successful because they pursued a cost leadership strategy and firms with low market share were successful because they used market segmentation to focus on a small but profitable market niche. Firms in the middle were less profitable because they did not have a viable generic strategy. Combining multiple strategies is successful in only one case. Combining a market segmentation strategy with a product differentiation strategy is an effective way of matching your firm’s product strategy (supply side) to the characteristics of your target market segments (demand side). But combinations like cost leadership with product differentiation are hard (but not impossible) to implement due to the potential for conflict between cost minimization and the additional cost of valueadded differentiation. Since that time, some commentators have made a distinction between cost leadership, that is, low cost strategies, and best cost strategies. They claim that a low cost strategy is rarely able to provide a sustainable competitive advantage. In most cases firms end up in price wars. Instead, they claim a best cost strategy is preferred. This involves providing the best value for a relatively low price. Contents [hide] 1 Cost Leadership Strategy 2 Differentiation Strategy 3 Segmentation Strategy 4 Recent developments 5 Criticisms of generic strategies 6 References 7 External links [edit] Cost Leadership Strategy This strategy emphasizes efficiency. By producing high volumes of standardized products, the firm hopes to take advantage of economies of scale and experience curve effects. The product is often a basic no-frills product that is produced at a relatively low cost and made available to a very large customer base. Maintaining this strategy requires a continuous search for cost reductions in all aspects of the business. The associated distribution strategy is to obtain the most extensive distribution possible. Promotional strategy often involves trying to make a virtue out of low cost product features. To be successful, this strategy usually requires a considerable market share advantage or preferential access to raw materials, components, labour, or some other important input. Without one or more of these advantages, the strategy can easily be mimicked by competitors. Successful implementation also benefits from: process engineering skills products designed for ease of manufacture sustained access to inexpensive capital close supervision of labour tight cost control incentives based on quantitative targets. Examples include low-cost airlines such as EasyJet and Southwest Airlines, and supermarkets such as KwikSave. [edit] Differentiation Strategy Differentiation involves creating a product that is perceived as unique. The unique features or benefits should provide superior value for the customer if this strategy is to be successful. Because customers see the product as unrivaled and unequaled, the price elasticity of demand tends to be reduced and customers tend to be more brand loyal. This can provide considerable insulation from competition. However there are usually additional costs associated with the differentiating product features and this could require a premium pricing strategy. To maintain this strategy the firm should have: strong research and development skills strong product engineering skills strong creativity skills good cooperation with distribution channels strong marketing skills incentives based on subjective measures be able to communicate the importance of the differentiating product characteristics stress continuous improvement and innovation attract highly skilled, creative people [edit] Segmentation Strategy In this strategy the firm concentrates on a select few target markets. It is also called a focus strategy or niche strategy. It is hoped that by focusing your marketing efforts on one or two narrow market segments and tailoring your marketing mix to these specialized markets, you can better meet the needs of that target market. The firm typically looks to gain a competitive advantage through effectiveness rather than efficiency. It is most suitable for relatively small firms but can be used by any company. As a focus strategy it may be used to select targets that are less vulnerable to substitutes or where a competition is weakest to earn above-average return on investments. [edit] Recent developments Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersma (1993) have modified Porter's three strategies to describe three basic "value disciplines" that can create customer value and provide a competitive advantage. They are operational excellence, product innovation, and customer intimacy. [edit] Criticisms of generic strategies Several commentators have questioned the use of generic strategies claiming they lack specificity, lack flexibility, and are limiting. In many cases trying to apply generic strategies is like trying to fit a round peg into one of three square holes: You might get the peg into one of the holes, but it will not be a good fit. In particular, Millar (1992) questions the notion of being "caught in the middle". He claims that there is a viable middle ground between strategies. Many companies, for example, have entered a market as a niche player and gradually expanded. According to Baden-Fuller and Stopford (1992) the most successful companies are the ones that can resolve what they call "the dilemma of opposites". The purpose of a business Some would argue that the main purpose of a business is to maximize profits for its owners, or in the case of a publicly-traded company, its stockholders. The late economist Milton Friedman was a proponent of this view and many bottom-line fundamentalists used his 1970 historic statement to this effect to justify a "Darwinomics" approach to doing business. Others would say that its principal purpose is to serve the interests of a larger group of stakeholders, including employees, customers, and even society as a whole. Most philosophers would agree, however, that business activities ought to comport with legal and moral strictures. One proponent of this philosophy has been U.S. businessman-turned-futurist John Renesch [1] who writes, "Corporations are human-made organisms, associations of human beings. To see this association as having one solitary purpose and responsibility, to grow only in economic terms, is such an extreme view that implosions like what happened to Enron, WorldCom and other corporate collapses will become more and more commonplace." Anu Agha, ex-chairperson of Thermax Limited, once said, "We survive by breathing but we can't say we live to breathe. Likewise, making money is very important for a business to survive, but money alone cannot be the reason for business to exist". Profit maximization is extremely relevant when top management is mandated with the job of selecting the right strategy for the business. According to Michael Porter, the primary goal for any business strategy exercise must be that of maximizing profitability. Peter Drucker defined the very purpose of business as creating a satisfied customer. This definition is also useful in evaluating to what extent a business is succeeding in fulfilling its stated purpose. Many observers would hold that concepts such as economic value added (EVA) are useful in balancing profit-making objectives with other ends. They argue that sustainable financial returns are not possible without taking into account the aspirations and interests of other stakeholders (customers, employees, society, environment). This conception suggests that a principal challenge for a business is to balance the interests of parties affected by the business, interests that are sometimes in conflict with one another. [edit] Contract theory Advocates of business contract theory believe that a business is a community of participants organized around a common purpose. These participants have legitimate interests in how the business is conducted and, therefore, they have legitimate rights over its affairs. Most contract theorists see the enterprise being run by employees and managers as a kind of representative democracy. [edit] Stakeholder theory Stakeholder theorists believe that people who have legitimate interests in a business also ought to have voice in how it is run, notwithstanding the fact that they do not have ownership in the business. The obvious non-owner, stakeholders are the employees. However, stakeholder theorists take contract theory a step further, maintaining that people outside of the business enterprise ought to have a say in how the business operates. Thus, for example, consumers, even community members who could be affected by what the business does, for example, by the pollutants of a factory, ought to have some control over the business