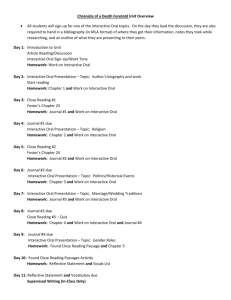

1 - EJOLTs

advertisement