Fulbright – MACECE Paper Kaylee Steck June 2015 Understanding

advertisement

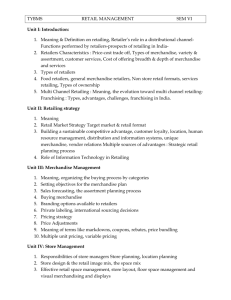

Fulbright – MACECE Paper Kaylee Steck June 2015 Understanding Experiences of Small Actors in Retail Development I. Introduction My research seeks to understand retail development in Morocco from the perspective of small grocers. Within the retail sector, there are four types of food retailers. First, there are fullservice small stores, such as kiosks and shops selling groceries, or specializing in meat, fruit, vegetables, or baked goods. These stores tend to be independent and have low margins and limited inventories. Second, there are open-air and covered markets of small retailers, or a mix of small retailers and wholesalers. These two types form a category called small retailing or proximity commerce, which refers to traditional stores or markets that are conveniently located near consumers.1 Third, there are small self-service stores including hard discounts and convenience stores, such as those located at rest stops or gas stations, and increasingly in urban neighborhoods. Fourth, there are large self-service stores – supermarkets and hypermarkets.2 These stores have large inventories and are often located in high-income areas of cities, which can to be difficult to reach by public transportation.3 This paper refers to the third and fourth store types as modern retailers. My initial research experience has led me to shift my focus from modern retailers toward small retailers having determined that they retain great significance. This paper considers different dimensions of small retailers’ importance in Morocco, and provides an historical overview of national economic development policies in Morocco since Independence in order to 1 This paper uses the terms small retail and proximity commerce interchangeably. This paper will not distinguish the various large formats; ‘supermarkets’ is used for any large-format store unless noted. 3 My classification of food retailers borrows from an article on food retailing in Latin America, which shares several similarities to the state of food retailing in Morocco. See: Thomas Reardon and Julio A. Berdegué, “The Rapid Rise of Supermarkets in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities for Development,” Development Policy Review 20, no. 4 (2002): 371–88. 2 1 understand their impacts on the retail sector generally, and on small grocers and other forms of proximity commerce in particular. After setting the scene historically, this paper highlights challenges to developing proximity commerce from the vantage point of research in Meknes, and then discusses how the fieldwork component of my project should lead to an understanding of these challenges from the perspective of small grocers. Finally, it concludes with a brief summary of development approaches that are sensitive to small retailers. 2 II. The Significance of Small Retailing in Morocco The retail sector in Morocco represents over 10 percent of GDP and employs roughly 13 percent of the labor force.4 In 2013, retailing was among the main branches to create the most jobs in the services sector.5 Small retailing remains dominant despite the recent introduction of supermarkets in urban areas. According to a recent article in La Vie Éco, modern retailing in Morocco represents less than 15 percent of the market. 6 Supermarket impact is muted in developing countries given barriers to consumption, such as low levels of disposable income, consumption patterns,7 and inadequate transportation infrastructure.8 Some key factors of rapid supermarket growth are urbanization; entry of women into the workforce, which creates more demand for processed food to save cooking time; and rapid growth per capita income.9 In Morocco, less than one in four women are employed.10 Between 1990 and 2003, when several domestic and foreign supermarket chains appeared in Morocco, GDP per capita growth was weak compared to other non-oil and politically stable countries in the Middle East and North Africa.11 Low levels of women in the workforce and slow growth in per capita income have impeded the development of a substantial consumer class for mass retailing in Morocco. A general conclusion is that the large-retail format has not been fully “Retailing in Morocco,” Euromonitor International, December 2014, http://www.euromonitor.com/retailing-in-morocco/report. “Activite, Emploi et Chomage,” Site Institutionnel Du Haut-Commissariat Au Plan Du Royaume Du Maroc, 2013, http://www.hcp.ma/. 6 “Les Enseignes de Grande Distribution À L’assaut Des Petites et Moyennes Villes,” La Vie Eco, accessed January 25, 2015, http://www.lavieeco.com/news/economie/les-enseignes-de-grande-distribution-a-l-assaut-des-petites-et-moyennes-villes28175.html. 7 The highly specialized nature of small-scale food retailing in developing countries means that consumers must frequently shop at several stores to meet their food needs. See: E. Kaynak and S.T. Cavusgil, “The Evolution of Food Retailing Systems: Contrasting the Experience of Developed and Developing Countries,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 10, no. 3 (1982): 252. 8 Tomasz Lenartowicz and Sridhar Balasubramanian, “Practices and Performance of Small Retail Stores in Developing Economies,” Journal of International Marketing 17, no. 1 (2009): 58–90; Kaynak and Cavusgil, “The Evolution of Food Retailing Systems: Contrasting the Experience of Developed and Developing Countries,” 262. 9 Reardon and Berdegué, “The Rapid Rise of Supermarkets in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities for Development,” 376. 10 “Morocco’s Workplace Gender Gap Widens - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East,” Al-Monitor, accessed June 4, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/business/2014/12/morocco-women-unemployment-discrimination-workplace-gender.html. 11 International Monetary Fund, Morocco: Selected Issues (International Monetary Fund, 2005), 6. 4 5 3 integrated into Moroccan patterns of consumption, despite having made its debut over two decades ago. Small retailing retains great significance both in economic and cultural terms, and serves the important role of supporting Moroccan consumers. In particular, the neighborhood grocery store (hanout in Moroccan Arabic) has endured despite the influx of more modern and lowerprice supermarkets. The reasons for this institution’s resilience cannot be understood without studying its various functions in Moroccan society. Hanouts are hubs of social and economic activity that build loyal customer networks through proximity and trusting relationships. They meet the needs of Moroccan consumers by providing easy access to small quantities of staple foods and household supplies at affordable prices. Shopping at a hanout is a quick, customized experience with the benefit of special services, like home delivery of heavy gas canisters for heating water and cooking. Hanouts offer their clients several other advantages. They create a sense of neighborhood safety by keeping long hours and getting to know their customers personally; they give advice as rental agents and matchmakers; and they accommodate traditional rhythms of daily life, such as prayer and meal times. American cultural anthropologist Rachel Newcomb describes these rhythms in her study of modern food and consumption in Fes: “The market, which closes in the afternoon, is usually open in the morning to accommodate the traditional midday meal, with commerce quieting down around the time of the lunchtime call to prayer, then picking up again briefly afterward as shoppers grab a last-minute ingredient on their way home from the mosque.”12 Rachel Newcomb, “Modern Citizens, Modern Food: Taste and the Rise of the Moroccan Citizen-Consumer,” in Senses and Citizenships: Embodying Political Life, Routledge Studies in Anthropology (Routledge, 2013), 169. 12 4 Finally, hanouts provide food security in cash scarce communities by extending credit to their clients. In the absence of formal contracts and legal protections, credit is given on a trust basis between sellers and buyers, further reinforcing the socially embedded nature of the neighborhood retailer. By entering into informal arrangements with clients based on mutual dependency, hanouts ease the strain of economic hardship on low-income consumers, and reduce the stress of navigating a changing food distribution system for large segments of society. In recent years, modern retailers have spilled out of upper-income neighborhoods and major cities into middle-income neighborhoods and medium-sized cities, hoping to attract a larger segment of Moroccan consumers with low prices and austere presentation (such as the Turkish discounter BIM and the Moroccan supermarket Acima). This strategy combines the locational convenience of a hanout and the efficiency of a supermarket. Ultimately, the decentralized and local aspects of small retailing provide a model for supermarkets to downsize and proliferate, and to better meet the needs of Moroccan consumers. Despite the significance of small retailing in Morocco, the dominant narrative in retail development literature is that supermarkets will replace small shops. This means that previous retail studies in developing countries have concentrated primarily on the modernization of distribution channels by importing marketing knowledge and institutions from more developed countries, without considering the value of local knowledge and institutions. 13 My Fulbright research aims to address the general lack of empirical research on small retailers in developing A. Goldman, “The Transfer of Retailing Technology into the Less Developed Countries: The Case of the Supermarket,” Journal of Retailing 57, no. 2 (1981): 5–29; Kaynak and Cavusgil, “The Evolution of Food Retailing Systems: Contrasting the Experience of Developed and Developing Countries”; S. Samiee, “Retail and Channel Considerations in Developing Countries, a Review,” Journal of Business Research 27, no. 2 (1993): 103–30; N.M. Coe and N. Wrigley, “Host Economy Impacts of Transnational Retail: The Research Agenda,” Journal of Economic Geography 7, no. 4 (2007): 341–71; T. Reardon, S. Henson, and J. Berdegue, “‘Proactive Fast-Tracking’ Diffusion of Supermarkets in Developing Countries: Implications for Market Institutions and Trade,” Journal of Economic Geography 7, no. 4 (2007): 399–431; Abdelmajid Amine and Najoua Lazzaoui, “Shoppers’ Reactions to Modern Food Retailing Systems in an Emerging Country: The Case of Morocco,” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 39, no. 8 (2011): 562–81; Marta Ortiz-Buonafina, “The Evolution of Retail Institutions: A Case Study of the Guatemalan Retail Sector,” Journal of Macromarketing 12, no. 2 (1992): 16–27. 13 5 economies, and ultimately, to understand some challenges of developing proximity commerce in Morocco from a small retail perspective. 6 III. Post Independence Economic Development Policies in Morocco This section provides an overview of national economic development policies in Morocco since Independence in order to understand their effects on the retail sector and on small retailers in particular. In the 1950s and early 1960s, following the success of large-scale government spending in post-war Europe, the model of economic development that affected policy throughout much of the world focused on large-scale, state-run enterprises. This model encouraged government industrialization, through the nationalization of resources, industry, and financial institutions. Morocco implemented this model of economic development in the 1960s and 1970s, pursuing large-scale projects and expanding government bureaucracy. The state extended its control over major industries, built infrastructure, and expanded social services. However, this model was costly and large portions of the population did not benefit from its policies, especially in rural areas, where the number of people living in poverty increased by one million between 1960 and 1977. By 1983, Morocco’s debt was 85 percent of GDP and the government faced severe budget deficits.14 In response, Morocco subscribed to the structural adjustment programs of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. These programs offered fund packages in exchange for the implementation of policies that favored economic austerity, free trade, deregulation, and privatization. The implementation of neoliberal policies entailed a fundamental shift from the state driven planning of the past to a free market strategy, which alienated populations dependent on public sector employment and services, as well as a business elite formerly protected by tariffs and monopolies. While these reforms helped decrease budget deficits by the mid-1990s, a Shana Cohen and Larabi Jaidi, “Debating and Implementing ‘Development’ in Morocco,” in Morocco: Globalization and Its Consequences, 1 edition (New York: Routledge, 2006), 37. 14 7 significant decrease in public sector expenditures in the 1980s contributed to social unrest, increasing inequalities, and economic instability.15 In subsequent decades, measures were adopted to respond to the negative outcomes of structural adjustment programs. Academics and activists called for the implementation of local development experiments to address problems of poverty and inequality. 16 According to the United Nations Development Program, local development is the carrying out of actions to improve people’s living conditions in a particular region; it is a participatory process that improves local capacities through knowledge sharing.17 The promotion of local development as an alternative solution to alleviate issues of unemployment and poverty in Morocco began at the end of the 1980s, when associations gradually became involved in areas such as informal education, health, and assistance of low-income populations. Later, they became involved in employment, small enterprises, and construction. Local development accelerated through the 1990s with the appearance of tens of thousands of community development organizations; the creation of regional centers for investment (Centres Regionaux d’Investissment) to simplify local business regulation; the development of micro-credit organizations such as Al Amana and Zakoura; and the creation of the Mohammed V Foundation in 1999. The strength of these new partnerships with civil society was enhanced with the launch of the National Initiative for Human Development (INDH), and the 2002 municipal charter, which gave local government more autonomy in economic and social development, and created an external inspecting body called the Regional Courts of Hsain Ilahiane and John Sherry, “Joutia: Street Vendor Entrepreneurship and the Informal Economy of Information and Communication Technologies in Morocco,” The Journal of North African Studies 13, no. 2 (June 1, 2008): 243–55. 16 Cohen and Jaidi, “Debating and Implementing ‘Development’ in Morocco,” 19–20. 17 “Local Development,” United Nations Development Programme, 2014, http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/ourwork/environmentandenergy/strategic_themes/local_development.html. 15 8 Accounts to audit the management of public enterprises. 18 However, these projects have not removed all obstacles, and the process of local development remains challenging given certain deficiencies in human capital, resources, and market experience. Nacer El Kadiri and Jean Lapeze, “The Dynamics of Territorial Development in Morocco,” in Development on the Ground: Clusters, Networks and Regions in Emerging Economies (London: Routledge, 2007), 75–93. 18 9 IV. The Effects of Economic Development Policies in Retailing The structural adjustment programs of the 1980s gave rise to conditions that would promote retail development in subsequent decades. The entrance of foreign distributors such as Metro Cash and Carry in the early 1990s, and Auchan, Ahold, and Carrefour in the 2000s was supported by government policies promoting free trade, privatization, and foreign direct investment. However, structural adjustment policies also created new barriers to retail development; the drastic reduction in government and parastatal employment during the last two decades of the twentieth century, as well as inadequate public investment into rural areas contributed to a trend of rural-urban migration, and led millions of workers to pursue jobs outside of the formal economy. The informal economy plays an important role in developing countries. In 2000, the urban informal sector of Morocco represented more than 15 percent of the gross domestic product and employed more than 50 percent of the working urban population. 19 In 2007, the informal economy was estimated to make up 90 percent of all retail outlets. Informal retail activities are problematic from a development perspective for multiple reasons; they assist trade in contraband and counterfeits, and they operate outside of regulatory purview without accurate accounts or adequate conditions. 20 Many small retailers, such as grocers, still operate partly within the informal sector. Due to the promotion of local development in recent years, new programs have been created to formalize small retailing. In 2008, the Moroccan Ministry of Trade in partnership with the Union Générale des Enterprises et Professions (UGEP) launched Rawaj, a program designed to modernize local businesses spaces. Government documents and news reports available online 19 20 Ilahiane and Sherry, “Joutia.” Oxford Business Group, The Report: Emerging Morocco 2007 (Oxford Business Group, n.d.). 10 lack a unified vision of the project’s scope and goals. At the very minimum, this plan provides partial funding for small retailers to buy and install new store appliances in order to integrate into the modern retail landscape. A similar program called Hanouty began in 2007 as a private sector attempt to transform small neighborhood stores into a recognized chain that unified their services and modernized their shops. Participants were required to pay 5,000 Moroccan Dirhams (MAD) in rent, and an advance of 30,000 MAD to receive a loan of 500,000 MAD from BMCE Bank for purchasing new store appliances and products. According to news reports, 21 participants felt they were overcharged for appliances, and accused the program for delivering nearly expired products, and making false promises to install automatic windows and reimburse transportation expenses and utilities. Moreover, participants claim they did not understand the contract terms, and were surprised to be tied to their loans after the program failed and was dismantled in 2012. More recently INDH launched a program in Sidi Bernoussi, Casablanca to organize proximity commerce by moving itinerant retailers or street hawkers into permanent stands with regular business hours. The cost to participants is 50 MAD per day, an advance of 7,000 MAD, and the cost of rent.22 These expenses certainly make participation in this program prohibitive to many, but the program overall reflects a concerted effort by the government to start supporting small retailers. Additional support is available through Moroccan Chambers of Commerce, which represent commercial interests on the regional level. In March, The Meknes Chamber of Commerce held a meeting to inform shop owners of a training program in accounting and “Victims of Hanouty Seek Help from Benkiran,” Zapress, accessed May 14, 2014, http://www.zapress.com/node/87458; “Victims of Hanouty Stage a Protest in Casablanca,” Hespress, November 18, 2009, http://www.hespress.com/faitsdivers/16698.html; “Hanouty: The Illusion That Bankrupted Hundreds of Victims,” Maghress, December 24, 2009, http://www.maghress.com/soussinfos/952. 22 “Debate Due to a Project for Proximity Commerce in Bernoussi, Casablanca,” Almassae Press, May 28, 2015, http://www.almassaepress.com. 21 11 management; it will offer a tax incentive and other benefits to participants.23 These programs represent a growing abundance of local or locally aware development initiatives that leave a lot to be desired in terms of addressing the significant challenges of developing proximity commerce. 23 Information based on my attendance of the meeting. 12 V. Challenges of Developing Proximity Commerce This section draws on news reports, participant-observation, academic literature, and informal interviews with small retailers and development organizations to deliver an overview of challenges in developing of proximity commerce, and to provide a backdrop for my case study. The themes of regulation, implementation, coordination, and operation highlight several challenges of developing proximity commerce in Morocco, and likely apply in other emerging markets. Morocco lacks legal measures to regulate supermarket expansion. In the absence of legal barriers to market access, supermarkets can open multiple outlets in a single city, thereby reducing the number of competitors. This is the case with Marjane, which owns the majority of selling space in several cities, and is the largest player in the supermarket segment. Label’Vie is its closest competitor, and together they hold a market share of 90 percent in the supermarket sector.24 In Meknes, Marjane owns three of the total five supermarkets, and Label’Vie owns the remaining two. These companies have recently developed retailing formats to compete with small retailers by implementing proximity and promotional strategies. In particular, the Turkish discounter BIM has expanded rapidly into popular neighborhoods, adding one hundred and fifty points of sale between 2011 and 2014.25 In the long term, unregulated supermarket expansion will damage local economic prospects by marginalizing actors in proximity commerce. Small retailers also call for more regulation of distribution companies. In May, a meeting was held at the headquarters of the Professional Association of Grocers in Casablanca. “Les Enseignes de Grande Distribution À L’assaut Des Petites et Moyennes Villes.” “Moroccans Replace Moul Hanout with Supermarkets,” Hespress, January 11, 2015, http://www.hespress.com/economie/251286.html. 24 25 13 Association members expressed a lack of trust between retailers and distributors. Specifically, they said certain distributors refuse to give invoices with small deliveries, and refuse to replace expired goods, especially in lower-income neighborhoods. Invoices let grocers track their purchases and companies track their sales for tax purposes. In place of invoices, some companies give bon de livraison or a delivery slip, which is not as rigorous for accounting purposes. Implementing local programs is another theme that sheds light on several development challenges, such as the need for non-uniform approaches and assessments in a resource and information poor environment, where mistrust and lack of transparency hinder cooperation. Development programs for proximity commerce need to be flexible in order to accommodate differences in operational capabilities and management styles of small retailers. However, the creation and implementation of several approaches based on local needs instead of one top-down approach meets difficulties where there are deficiencies in human resources and funding.26 These deficiencies also hinder data collection and project assessments. Rawaj was launched seven years ago to develop proximity commerce, yet there has been very little evaluation of the project’s impact. According to an article from 2010, Rawaj benefited four hundred shops in Fes and twelve hundred shops from Souk Masira in Sidi Moumen. The article also says that the program aimed to support ten thousand five hundred traders by 2012; whether this goal was reached is undetermined. 27 Without the necessary resources to carry out assessments and provide support on the ground, development projects lose credibility in their communities, and lack transparency and overall quality. An information and resource poor environment, especially in rural areas, does not only mean limited flexibility and assessment capabilities, but also a lack of publicity campaigns to El Kadiri and Lapeze, “The Dynamics of Territorial Development in Morocco.” “National Council for the General Union of Enterprises and Professions,” Maghress, April 22, 2010, http://www.maghress.com/alalam/26538. 26 27 14 effectively publicize available programs and services. This general lack of information further marginalizes local retailers and contributes to the atmosphere of mistrust surrounding development interventions. Based on informal conversations with small retailers, there is a prevailing fear of exploitation by companies, banks, and government programs. This atmosphere is further compounded by corruption and political infighting in organizations that represent business interests. At a recent meeting of small grocers held at UGEP in Casablanca, members discussed the impending break up of their association due to political interests of other associations at the Union. More coordination between associations, regional institutions of governance, such as Chambers of Commerce, and companies is required to provide proper regulation, support, and direction for development programs, and to address the lack of availability and marked inequality of access to resources that do exist. Coordination is further needed to spread accurate information, encourage participation, and create programs that are more sensitive to small retailers’ needs. On the ground, the operation of small businesses presents several development challenges. The lack of information processing technologies and skills for inventory and accounting purposes, and the wide spread culture of credit pose major challenges to increasing the level of managerial sophistication, specifically with regard to financial reporting. Despite these challenges, small retailers are obliged by law to track their daily earnings and fill out specific forms regarding finance procedures. 15 According to article 145 of the 2014 Financial Law,28 small retailers have to record their daily revenue and keep the documents that prove purchases and sales.29 This law is currently impossible to implement given that small retailers do not use sales receipts or consistently receive invoices from distributors, making it difficult to routinely maintain financial evidence for sales and purchases. Until recently, the prevailing tax regime for small retailers has not required rigorous financial reporting. However, as part of its effort to organize the retail sector, the government is trying to encourage a mass transition to la comptabilité or muḥasiba (accountability). Small retailers are becoming increasingly vocal about the challenges they face in retail development. In February 2015, a group of small retailers from different associations formed a collective to protest in front of Parliament. Their demands included stopping the fast growth of supermarkets and their concentration in popular neighborhoods; limiting oppressive tax audits; providing basic social protections such as health coverage and affordable housing; developing the trade sector with respect to maintaining a balance between large and small retailers; and opening a serious dialogue for their participation in the process of addressing these demands.30 Despite recent trends in local development, small retailers remain marginalized from decisionmaking processes. Moreover, their experiences are largely absent from literature dealing with retail development. My research aims to address this absence by developing an internal perspective on retail development through interviews with small grocers. 28 This particular article was protested and rewritten to reflect some demands of small retailers in article 146. “Mohamed Dahbi: The Financial Law Will Expose Small Retailers to Coercion,” Anfaspress, June 8, 2014, http://www.anfaspress.com/index.php/2014-06-06-15-26-50/item/10289-2014-06-06-18-12-03. 30 “Moul Hanout Collective Goes Out to Protest,” Hespress, January 29, 2015, http://www.hespress.com/24-heures/253492.html. 29 16 VI. Case Study: Setting the Scene The fieldwork component of my project is a small-scale, qualitative case study that examines the hanout through interviews conducted in Meknes. My project aims to build on John Waterbury’s research in North for the Trade: The Life and Times of a Berber Merchant (1973). His work places the movements of Swasa grocers in the context of economic and political change in the twentieth century. Hanouts are known for their industrious Swasa owners who left their homes in the Sous region of Morocco to exploit new business opportunities created by the expansion of European sections of Moroccan cities, and the growth of salaried consumers in urban areas. By the mid-twentieth century, the Swasa had monopolized grocery trade and created an expansive business network that relied on private credit and other practices that were enforced internally. 31 The entrance of non-soussi merchants into grocery retailing has slowly eroded ethno-domination in the business. However, many Moroccans still associate this trade with the Soussi community. Waterbury’s research, conducted between 1966 and 1971, illuminates typical experiences of a trading community through interviews with a single grocer. This approach loosely informs my fieldwork, through which I hope to understand typical experiences of a contemporary trading community. I chose to focus on hanouts for several reasons; they are conveniently located in urban neighborhoods; have permanent shops; keep predictable stores hours; and form trusting relationships with their customers. Therefore, I conduct interviews by snowball sampling; I ask Moroccan friends to introduce me to their grocers in order to establish trust. I also make frequent purchases as a customer before asking to do an interview. All of my interviews take place at 31 John Waterbury, North for the Trade: The Life and Times of a Berber Merchant (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973). 17 shops during business hours. I ask a fixed set of open and closed questions in Moroccan Arabic to collect information about demographics, engagement in development programs, and needs or problems. I face several limitations in my fieldwork that are worth mentioning. I anticipated that cultural and linguistic asymmetries between the investigator and the investigated would determine how much and what kind of information would be shared. I also anticipated that some grocers would be suspicious of my interest in their business practices, especially given their fear of taxes and regulation. This is the main reason I decided not to ask grocers about their monthly income. Moreover, a question about income would likely produce false or inaccurate data given poor record keeping. I took several measures to prepare for challenges on the ground. I studied Moroccan Arabic fox six months prior to starting interviews; I researched small retailing in Morocco; and I designed questions that used familiar concepts and vocabulary, replacing complicated terminology like “development challenges” with “problems.” There were also limitations that I did not anticipate, such as the time commitment of building relationships with participants. Without a research team, I had to personally get to know each of my participants, before scheduling and conducting interviews. From start to end, this process can take up to a few weeks for each participant. During interviews, participants are usually multitasking, answering questions and dealing with customers at the same time. As a result, I end up repeating questions or simply not getting very detailed responses. 18 VII. Challenges of Developing Proximity Commerce: Internal Perspectives My conclusions are based on three months of interviews with a research network of twenty hanouts in eight neighborhoods.32 I did not choose these neighborhoods based on specific criteria; they are simply where I knew people who could introduce me to participants. In uppermiddle class neighborhoods, represented in this study by Hamriya and La Touran, there is a higher concentration of participants with relatively higher education levels and monthly revenue. This is explained by such factors as customers’ high purchasing power in these areas. Hanouts in Hamriya also benefit from proximity to government services and information. Store location is an important aspect to factor in when considering development challenges. For example, hanouts in the Old City have transportation problems because the streets are too narrow for trucks to make large deliveries. Hanouts in low-income neighborhoods have small profits because of low-income clients. Due to the nature of my research, I have not been able to conduct an equal number of interviews in each neighborhood. Therefore, I cannot provide a strong analysis of challenges based on store location. Rather, I would like to highlight location as an important dimension to consider for future research. On the basis of twenty interviews, the following discussion will explore some of the most commonly expressed challenges of developing proximity commerce. I have recorded thirty-one distinct challenges, nineteen of which are expressed by more than one participant. 33 The most frequent responses are credit (seventeen instances); lack of associations (nine instances); lack of accounting (eight instances); and lack of government support (six instances). Other frequently raised issues include taxes, lack of social protections, small profits, and lack of employees. 32 33 See Table A (p.22). The full results can be found in Table B (pp. 22-24). 19 Credit is seen as a challenge by 85 percent of the participants. In this context, credit is an interest free mechanism that allows customers to buy now and pay later. Grocers often track individual credit accounts using a notebook (carnet) or pieces of paper. This system is very disorganized, and papers with customer accounts are easily lost or destroyed. The process of repayment is also messy in that every customer negotiates his own repayment schedule, which is ultimately guaranteed by an unspoken social contract. Credit has social benefits such as providing food security in cash scarce neighborhoods, but it is a major risk for grocers. Many participants have suffered huge losses because clients disappeared with unpaid credit accounts. Some participants said they should get tax breaks for providing credit because it provides a security net for low-income citizens, who would otherwise lash out at the government. Even grocers who do not normally offer credit let their clients borrow from time to time because of social pressure. For example, one participant said that he normally charges an extra fee when he sells a glass bottle of soda in case the customer does not return the bottle. However, he does not charge his regular customers this fee out of respect, and now he loses money every time they forget to return a bottle. The problem of credit is connected to other development challenges, such as low-income clients, small profits, and the lack of sound accounting practices. Fortunately, many of the challenges of developing proximity commerce are interrelated. A program designed to address one problem, could also tackle other issues that stand in the way of increasing the economic well being of small retailers, who work long hours for small profits just to make ends meet. Participants also emphasized lack of support from the government and non-governmental organizations. This finding is not surprising given that existing programs are not well publicized, poorly implemented, and often require large financial commitments that are prohibitive to many 20 small retailers. The three development projects discussed in this paper, Rawaj, Hanouty, and the INDH project in Sidi Bernoussi, all require participants to pay hefty fees to benefit from program support. The general lack of awareness of programs is further illustrated by the fact that only one grocer in my sample benefited from the program Rawaj, and only 25 percent of participants said they knew of the program. Identifying these challenges is a necessary step to determining where policy interventions should start, and what additional resources are needed in order to adequately address the most pressing challenges from a small retail perspective. 21 Table A: Background Information of Sample Population Location Hamriya Experience (years) University Education level High School Middle School Primary school No formal education TOTAL Agdal < 10 >10 < 10 1 1 0 0 1 0 Ain Slougi > 10 Old City Sidi La Touran Marjane II Marjane Bouzekri III TOTAL >10 <10 >10 <10 >10 <10 >10 <10 >10 < 10 >10 < 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 3 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 6 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 2 0 1 0 1 0 6 3 0 1 0 0 2 1 2 20 Hamriya Ain Slougi Agdal Old City Table B: Participant Responses Location Participant Responses 34 Sidi Bouzekri La Touran Marjane II Marjane III TOTAL Credit 2 0 1 5 3 1 2 3 1734 Lack of associations 2 0 0 3 1 0 1 2 9 Lack of accounting 1 1 0 4 1 1 0 0 8 Lack of government support 2 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 6 17 out of 20 participants responded credit 22 Taxes 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 2 4 Lack of social protections 1 0 0 2 0 0 0 1 4 Small profit 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 Lack of employees 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 3 Low income clients 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 3 Lack of transportation 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 3 Just trying to make ends meet 0 1 0 2 0 0 0 0 3 Lack of education 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 2 Lack of negotiating power 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 Fluctuation in prices 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 Bad relationship with distributors 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 Fear of taxes 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Lack of organization in small retail 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Insufficient capital 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Lack of marketing strategies sales/promotions 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 Lack of time to learn about existing resources Competition from itinerant retailers 23 4 Disorganized tax collection Government does not understand the problem of credit Barriers to government support Government is not organized Long work hours Personal costs on top of business costs Lack of interest in continuing the profession Competition from Supermarkets Competition from other grocers Lack of appliances TOTAL 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 16 2 3 38 9 4 7 13 92 24 VIII. Conclusion: Critical Approaches to Developing Small Retailing This paper shows hanouts as places for social and economic transactions, for exchanges of money and advice, for drinking tea and making conversation. As much as they are vital hubs of local culture, hanouts are also considered undeveloped spaces and inefficient businesses that do not keep up with modern marketing and merchandising. In other words, they do not fit into the neoliberal order of mass retailing and consumption. My main recommendation is to recognize that this regime is not the only model for Morocco. Small retailers play an important role in shaping the direction of change too; their resilience in the face of state power to transform retailing across the country demands a more inclusive approach to development. One approach is to look at small and modern retailers as complementing each other in a distribution system that needs to provide for different segments of a society with high-income variance. Additionally, the retail sector needs to employ the population. In developing countries, where capital is costly, one can expect little capital-labor substitution. In Morocco, this expectation is confirmed by the fact that small retail continues to be labor intensive, and therefore serves as a buffer to unemployment and unrest.35 Another approach is to design programs that actually respond to small retailing needs, such as training in routinized transactions, which could result in a slow transition away from informal credit. The current government program to develop proximity commerce by subsidizing new store appliances is a cosmetic attempt to overhaul underlying operational structures that require more resources and time to transform. A more serious commitment to development that appreciates the value of proximity commerce is needed before we can expect to see change that reflects the needs of small retailers. 35 Ortiz-Buonafina, “The Evolution of Retail Institutions: A Case Study of the Guatemalan Retail Sector,” 25. 25 Bibliography “Activite, Emploi et Chomage.” Site Institutionnel Du Haut-Commissariat Au Plan Du Royaume Du Maroc, 2013. http://www.hcp.ma/. Amine, Abdelmajid, and Najoua Lazzaoui. “Shoppers’ Reactions to Modern Food Retailing Systems in an Emerging Country: The Case of Morocco.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 39, no. 8 (2011): 562–81. Coe, N.M., and N. Wrigley. “Host Economy Impacts of Transnational Retail: The Research Agenda.” Journal of Economic Geography 7, no. 4 (2007): 341–71. Cohen, Shana, and Larabi Jaidi. “Debating and Implementing ‘Development’ in Morocco.” In Morocco: Globalization and Its Consequences, 1 edition., 1–45. New York: Routledge, 2006. “Debate Due to a Project for Proximity Commerce in Bernoussi, Casablanca.” Almassae Press, May 28, 2015. http://www.almassaepress.com. El Kadiri, Nacer, and Jean Lapeze. “The Dynamics of Territorial Development in Morocco.” In Development on the Ground: Clusters, Networks and Regions in Emerging Economies, 75–93. London: Routledge, 2007. http://pi.lib.uchicago.edu/1001/cat/bib/6438409. Fund, International Monetary. Morocco: Selected Issues. International Monetary Fund, 2005. Goldman, A. “The Transfer of Retailing Technology into the Less Developed Countries: The Case of the Supermarket.” Journal of Retailing 57, no. 2 (1981): 5–29. Group, Oxford Business. The Report: Emerging Morocco 2007. Oxford Business Group, n.d. “Hanouty: The Illusion That Bankrupted Hundreds of Victims.” Maghress, December 24, 2009. http://www.maghress.com/soussinfos/952. Ilahiane, Hsain, and John Sherry. “Joutia: Street Vendor Entrepreneurship and the Informal Economy of Information and Communication Technologies in Morocco.” The Journal of North African Studies 13, no. 2 (June 1, 2008): 243–55. doi:10.1080/13629380801996570. Kaynak, E., and S.T. Cavusgil. “The Evolution of Food Retailing Systems: Contrasting the Experience of Developed and Developing Countries.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 10, no. 3 (1982): 249–69. Lenartowicz, Tomasz, and Sridhar Balasubramanian. “Practices and Performance of Small Retail Stores in Developing Economies.” Journal of International Marketing 17, no. 1 (2009): 58–90. “Les Enseignes de Grande Distribution À L’assaut Des Petites et Moyennes Villes.” La Vie Eco. Accessed January 25, 2015. http://www.lavieeco.com/news/economie/les-enseignes-degrande-distribution-a-l-assaut-des-petites-et-moyennes-villes-28175.html. “Local Development.” United Nations Development Programme, 2014. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/ourwork/environmentandenergy/strategic_th emes/local_development.html. “Mohamed Dahbi: The Financial Law Will Expose Small Retailers to Coercion.” Anfaspress, June 8, 2014. http://www.anfaspress.com/index.php/2014-06-06-15-26-50/item/102892014-06-06-18-12-03. “Moroccans Replace Moul Hanout with Supermarkets.” Hespress, January 11, 2015. http://www.hespress.com/economie/251286.html. “Morocco’s Workplace Gender Gap Widens - Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East.” AlMonitor. Accessed June 4, 2015. http://www.al- 26 monitor.com/pulse/business/2014/12/morocco-women-unemployment-discriminationworkplace-gender.html. “Moul Hanout Collective Goes Out to Protest.” Hespress, January 29, 2015. http://www.hespress.com/24-heures/253492.html. “National Council for the General Union of Enterprises and Professions.” Maghress, April 22, 2010. http://www.maghress.com/alalam/26538. Newcomb, Rachel. “Modern Citizens, Modern Food: Taste and the Rise of the Moroccan Citizen-Consumer.” In Senses and Citizenships: Embodying Political Life, Chapter 5. Routledge Studies in Anthropology. Routledge, 2013. Ortiz-Buonafina, Marta. “The Evolution of Retail Institutions: A Case Study of the Guatemalan Retail Sector.” Journal of Macromarketing 12, no. 2 (1992): 16–27. Reardon, T., S. Henson, and J. Berdegue. “‘Proactive Fast-Tracking’ Diffusion of Supermarkets in Developing Countries: Implications for Market Institutions and Trade.” Journal of Economic Geography 7, no. 4 (2007): 399–431. Reardon, Thomas, and Julio A. Berdegué. “The Rapid Rise of Supermarkets in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities for Development.” Development Policy Review 20, no. 4 (2002): 371–88. “Retailing in Morocco.” Euromonitor International, December 2014. http://www.euromonitor.com/retailing-in-morocco/report. Samiee, S. “Retail and Channel Considerations in Developing Countries, a Review.” Journal of Business Research 27, no. 2 (1993): 103–30. “Victims of Hanouty Seek Help from Benkiran.” Zapress. Accessed May 14, 2014. http://www.zapress.com/node/87458. “Victims of Hanouty Stage a Protest in Casablanca.” Hespress, November 18, 2009. http://www.hespress.com/faits-divers/16698.html. Waterbury, John. North for the Trade: The Life and Times of a Berber Merchant. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. 27