Stage 1 - Bath & North East Somerset Council

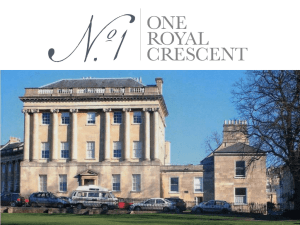

advertisement