International Finance

advertisement

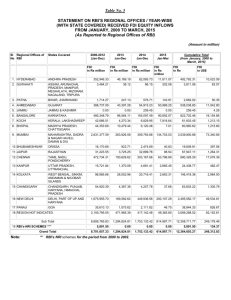

INBU 4200 INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT Lecture 13 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Cross Border Merges and Acquisitions and Greenfield Site Investment Entering a Foreign Market Any firm considering entering the foreign market must examine four basic issues: Which foreign markets/countries to enter? When to enter them (timing)? What scale (financial commitment)? What entry mode strategy should it use (organizational structure)? Three Categories of Entry Modes Exporting and Importing Exporting: The act of sending goods from one country to other nations. Manufacture at home; ship product overseas. Importing: The act of bringing goods into a country from other countries. Contractual entry Using contracts which permit foreign partners to manufacture and/or sell your products in another country. Franchising and licensing. Investment entry Direct investment by your company in another country for the purpose of producing and/or selling your product overseas. Investment Entry: FDI Foreign Direct Investment refers to business investment which acquires a long term and controlling interest in an enterprise operating in a country other than that of the investor. The percentage for classifying FDI control varies from country to country, however: The U.S., Japan, the UN, and the OECD use 10% stake in the voting stock of a foreign enterprise as constituting FDI. If it is less than 10% it is defined as portfolio investment. Quick History of FDI In the years after the Second World War global FDI was dominated by the United States. The US accounted for around three-quarters of new FDI between 1945 and 1960. FDI rose dramatically during the decade of the 1990s due in large measure to cross border merger and acquisitions activity. From 1990 to 2000, the stock of outstanding stock of foreign direct investment increased from $1.7 trillion to $6.1 trillion. Countries other than the US became major players. But FDI flows peaked at $1.4 trillion in the year 2000. FDI Since 2003 Since 2003, FDI has increased again spurred by a renewal in cross border mergers and acquisition activity. For 2005, FDI flows were estimated at just under $916 billion and the outstanding stock totaled $10 trillion. Preliminary data for 2006 suggests further growth in FDI. FDI flows for 2006 are estimated at $1.2 trillion, the second highest level since 2000. Visit: http://www.unctad.org/Templates/webflyer.asp?do cid=7993&intItemID=1634&lang=1 FDI: 1980 – 2005; Billions of US$ Notes to Previous Chart The previous chart segregates World FDI into three major categories. They, along with their definitions, are as follows: Developed Countries: World Bank definition based on Gross National Income per capita of $9,266 and above. About 40 countries. Developing Countries: World Bank definition based on Gross National Income per capita less than $9,266. About 125 countries. Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS): Refers to 11 former Soviet Republics: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. FDI 2005 by Region and Country, Billions of US$ and % of Total World Developed Countries UK US France Emerging Countries Amount $916 $542 $164 $ 99 $ 64 $374 China (with Hong Kong) China excluding Hong Kong Percent 100% 59% 18% 11% 7% 41% $108 $ 72 12% 8% Where does FDI go and where does it come from? Inward FDI: Foreign direct investment coming into a particular country. Historically, the developed countries have captured the majority of this inward investment. In recent years, however, an increasing percentage has gone to the developing countries (especially China and India). See Appendix 1 for a discussion of FDI impacts on developing countries. Outward FDI: Foreign direct investment leaving a particular country. Historically, developed countries have been the major FDI investors overseas. The United States is the single largest investor, followed by the UK and France. See Appendix 2 for data on US FDI Distribution of FDI by Region and Selected Countries; (Per cent) Average Annual FDI (Billions US$) 1999-2004 Basic Forms of FDI: Joint Ventures and Wholly Owned Subsidiaries FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT JOINT VENTURES WITH A FOEIGN PARTNER MERGER TO FORM A THIRD COMPANY WHOLLY OWNED SUBSIDIARIES GREENFIELD INVESTMENT ACQUISITIONS OF EXISTING COMPANIES Wholly Owned Subsidiary and Joint Ventures Wholly Owned Subsidiaries The foreign facility is entirely owned and controlled by a “single” parent. Honda U.S.A.; 100% owned by Honda (Japan) Apple Retail Japan; 100% owned by Apple USA (see Appendix 3) Joint Ventures Shared ownership arrangement and the creation of a new company. A separate company is created and jointly owned by two or more companies (or entities). Hong Kong Disneyland: Hong Kong Government (53%) and Walt Disney Co (47%). Starbucks Japan: Starbucks (50%) and Sazaby League (50%) (see Appendix 4) Mergers, Acquisitions, and Greenfield Mergers (two companies forming a new company): Sony Corporation and Bertelsmann AG completed a merger on August 5, 2004 of Sony Music Entertainment and Bertelsmann's BMG. The new music company, called Sony BMG, is equally owned (50/50) by Sony and Bertelsmann. Acquisition (one company acquiring another): Ford Motor Company bought 100% of Jaguar Cars Limited for $2.8 billion in 1990. Greenfield site investment (one company building a new facility): Haier Corporation built a $40 million refrigerator manufacturing facility in South Carolina in 2000. Cross Border M&A, the 1990s During the 1990s, cross border mergers and acquisitions increased dramatically. In 1991, the value of cross border M&A was estimated at just under $200 billion. By 2000, the value had grown to $1.2 trillion. This increase was fueled by global economic growth and increasing stock prices, especially the dot.com run-up. The relative importance of FDI was also shown in its percent of global GDP, increasing from 0.5% in 1991 to around 4% by 2000. Cross Border M&A 1991 - 2000 Cross Border M&A, 2001 The global economic slowdown in 2001 and falling stock prices contributed to a decline in cross border mergers and acquisitions. In 2001, the total value of cross border M&A at $594 billion was only half that of 2000. The number of cross-border M&A also declined from 7,800 in 2000 to 6,000 in 2001. Cross Border M&A, the Present Cross border M&A activity has recently accelerated. In 2005, the number of cross border M&A totaled 6,134 (20% increase over 2004) with a combined value of $716 billion (88% increase over 2004). The recent high level of M&A activity is accounted for by: Increasing economic growth, Rising stock prices. Growing involvement of private equity funds and hedge funds in M&A activity (see Appendix 5 for data). Ongoing liberalizations of country investment policies by individual governments (see Appendix 6). For a comparison of 2000 with 2005 and data on specific M&As see Appendix 7. Cross Border A&A by Private Equity and Hedge Funds, Number of Deals Regulatory Changes, 1992-2005 Barriers to Cross Border Acquisitions Even though governments have tended to liberalize their investment climate, barriers to cross border acquisitions still exist: These barriers can be classified as: Cultural Associated with potential investment in a different culture Domestic business arrangements Business arrangements which hamper acquisitions: Keiretsu in Japan Specific government restrictions or requirements Examples of Current Government Imposed Barriers Mexico: Prohibits foreign ownership of oil companies. Japan: Prohibits foreign ownership of mining companies. Canada: Requires a review of all acquisitions of Canadian companies. US: Foreign ownership of US airlines is limited to 25%. China: Foreign ownership of Chinese banks is limited to 25%. Australia: Foreign ownership of national newspapers is limited to 30%. India: Prohibits foreign ownership of retail business such as supermarkets and convenience stores. Trends in Cross Border M&A, % of Targets Greenfield Site Investment (GSI) Since there is little data regarding the value of GSI, we are forced to examine the actual number of projects. This data shows the following for 2005: Total: 9,488 by investor by destination Developed Countries: 8,057 (85%) 3,981 (42%) Developing Countries: 1,431 (15%) 5,507 (58%) Thus, most GSI originates from developed countries and takes place in developing countries. Popular Targets for GSI, 2005 Total by Destination: 9,488 (100%) European Union: 2,928 (30.9%) U.K. 514 (5.4%) France 358 (3.8%) United States: 527 (6%) Developing Asia: 3,323 (35%) China 1,196 (13%) India 564 (5.6%) Viet Nam 169 (1.8%) South East Europe and CIS 1,121 (11.8%) Russia 479 (5.1%) Latin America 543 (5.8%) Mexico 134 (1.4%) Africa 428 (4.5%) South Africa 59 (0.6%) FDI Theories Theory: The purpose is to “explain” or “predict” the behavior of a particular phenomena. For example, why do firms engage in FDI? The theoretical development of FDI began in the 1960s when models were advanced to explain the motives behind outward investments by U.S. multinationals (see Appendix 8). Prior to this time, theoretical modeling was concerned primarily with explaining international trade: Adam Smith: Theory of Absolute Advantage (1776) Heckscher-Ohlin: Theory of Factor Endowments (early 20th century). Early FDI Theory: 1960s Monopolistic Advantage Theory of FDI: Proposed by Stephen Hymer (1960, Ph.D. thesis, MIT). Hymer suggested specific firm monopolistic advantages over their competition in foreign markets provided firms with the incentive engage in FDI. Monopolistic advantage would allow firms to generate above average profits. Monopolistic advantages resulted from: superior production skills, patents, marketing abilities, capital size, management skills, or consumer goodwill on brand names. International Product Life Cycle Proposed by Raymond Vernon (1966) Vernon’s theory explains the “timing and location” of FDI Initially, firms undertake production in their home markets which are generally the highest income countries. During the next stage, the firm will begin to export, first to other high income countries and eventually to others. As the product matures and becomes standardized, the firm’s competitive strategy shifts from product advantage to securing a cost advantage. Control and risk avoidance are important here. In this stage the company is forced to seek lower cost production sites to remain competitive. This involves establishing manufacturing facilities overseas (FDI). Thus, Vernon suggest that firms undertake FDI at a particular stage in the life cycle of their production. International Product Life Cycle Quantity The U.S. and other developed countries New product Quantity Developing countries exports imports Maturing product Standardized product exports imports New product Maturing product Standardized product Eclectic Explanation of FDI The eclectic approach attempts to identify possible motivating factors affecting a firm’s decision to engage in FDI. Some of these factors focus on various market imperfection and include: Trade barriers Imperfect labor markets Other motivating factors include: Existence of Intangible assets (referred to as the internalization theory of FDI) Vertical integration Trade Barriers Trade barriers are factors which discourage the physical movement of goods and services from one country to another. Trade barriers arise from: Thus they have a potential negative impact on exporting and importing. Government policies, such as: Tariffs and quotas Natural factors, such as: Distance and ensuing transportation costs FDI is seen as a strategy for circumventing these trade barriers. Trade Barriers and FDI: Examples 1977: In response to U.S. import quotas on Japanese televisions, Japanese TV manufacturers opened production facilities in the U.S. 1980s: In response to the 1981 voluntary restraint agreement between the U.S. and Japan Japanese automobile manufacturers established production facilities in the U.S. Matsushita, Sony Corporation, Hitachi, and Sanyo Electric Company Honda and Nissan in 1982 and 1983. Toyota, Mazda, and Mitsubishi in the mid-1980s. 2000: In response to high transportation costs, Haier Corporation (China) established a $40 million refrigerator manufacturing facility in South Carolina. Imperfect Labor Markets Refers to firms locating in foreign countries because of under-priced labor costs (relative to its productivity) in those foreign countries. Why is labor under-priced in certain countries? Because labor cannot move freely across national borders to take advantage of higher wages elsewhere. Imperfect Labor Markets explains FDI investment in: Manufacturing (China, Mexico, Eastern Europe) Nike in China. Services (India; call centers). United Airlines in India. Labor Market Costs Around the World (2003) Country Hourly Cost Persistent wage differentials across countries is often noted as one of the major reasons MNCs invest in FDI in developing nations. Germany U.S. Japan Korea Taiwan China about 1/4 the Mexico China cost of labor in Mexico. Indonesia $31.25 $21.98 $20.09 $10.28 $5.84 $2.48 $0.60 $0.22 Internalization Theory of FDI Suggests that firms possessing valuable intangible assets (e.g., technology, managerial talent, brand loyalty) will use their own subsidiaries, rather than “local” host country firms to capture returns. Why? Avoids misuse of assets by local partners Avoids sharing technology. Insures full control. These firms “internalize” their foreign activities. Through strategies involving either wholly owned subsidiaries or controlling interest in joint ventures. This is Apple Retail’s strategy (see Appendix 3). Vertical Integration Theory of FDI Some firms engage in FDI to stabilize a critical supply chain (of inputs). Provides these firms with the potential for a low-cost competitive advantage. E.g., In 1996, Dole Food Company purchased Pascual Hermanos, the largest grower of fruit and vegetables in Spain. Referred to as backward (or downstream) integration. Majority of FDI involve backward integration Firms may also engage in FDI to promote distribution, product sales and service to final buyers. E.g., Automobile manufacturing companies establishing car dealerships in other countries (over 1,000 Honda dealerships in the United States). Referred to as forward (or upstream) integration. Political Risk and FDI Defined: Refers to the potential losses to a foreign firm resulting from adverse political actions taken by host governments. These adverse political actions include: Changes in operating regulations affecting foreign firms (see Appendix 9; Coca-Cola in India). Expropriation (confiscation) of the foreign firm’s assets by the host government. Cuba expropriated $1 billion worth of US businesses in 1960 (US oil refineries, including Texaco and all US banks including, First National Bank of New York) Three Political Risk Components Transfer Risk Operational Risk Uncertainty regarding cross-border flows of capital (i.e., the repatriation of profits). Imposition of capital controls, changes in withholding taxes on dividends. Uncertainty regarding host countries policies and behavior with regard to firm’s operations. Changes in environmental regulations, local content requirements, minimum wage laws, and corruption. See Appendix 10 for a discussion of bribery Control Risk Uncertainty regarding control or ownership of assets Changes in restrictions on maximum ownership by non-resident firms, nationalization of foreign assets. Assessing Political Risk Political risk is potentially one of the biggest risks that global firms face. Firms must constantly assess and manage political risk. What are some external sources for doing so? Corruption Indexes http://www.transparency.org/ (no fee) Country Analysis http://www.state.gov/countries/ http://library.uncc.edu/display/?dept=reference&format =open&page=68 Political Risk Indexes http://www.countrydata.com/ (fee based) Managing (Hedging) Political Risk Geographic diversification Simply put, don’t put all of your eggs in one basket. Minimize exposure Form joint ventures with local companies. Join a consortium of international companies to undertake FDI. Local government may be less inclined to expropriate assets from their own citizens. Local government may be less inclined to expropriate assets from a variety of countries all at once. Finance projects with local borrowing. Insuring Against Political Risk Political risk insurance provided by: The Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), a U.S. government organization. OPIC offers insurance against: The inconvertibility of foreign currencies. Expropriation of U.S.-owned assets. Destruction of U.S.-owned physical properties due to war, revolution, and other violent political events in foreign countries. Loss of business income due to political violence Political risk insurance is available for investments in new ventures and expansions of existing enterprises Visit: http://www.opic.gov/ Appendix 1: Impact and Importance of FDI on Developing Countries FDI Dominates Developing Countries’ Capital Inflows FDI is also More Stable than Equity and Short-Term Debt Appendix 2: Data on US Inward FDI by Year and Country Inward FDI: To the United States Foreign Direct Investment in the United States, 1997-2006 (p) (in billions of U.S. dollars) $321.3 B $350 $289.4 B $300 $250 $179.0 B $183.6 B $167.0 B $200 $133.2 B $109.8 B $150 $105.6 B $84.4 B $64.0 B $100 $50 $0 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, International Transactions Account Data 2004 2005 2006 (p) FDI Investment in the US by Country Foreign Direct Investment in the United States by Leading Countries, 2005- 2006 (p) $29.0 B $29.7 B $29.7 B $30,000 $27.0 B $25,000 $18.1 B $20,000 $14.1 B $18.0 B $16.2 B $15,000 $7.1 B $10,000 $4.4 B $5,000 $0 United Kingdom France Netherlands 2005 Japan 2006 (p) Source: Bureau of Econom ic Anlaysis, International Transactions Accounts Germany Appendix 3: Apple Retail Apple Retail has used a wholly owned subsidiary arrangement when engaging in FDI. The following slides discuss this. Wholly Owned: Apple Retail Apple’s retail store strategy has been to enter a foreign country under a wholly owned structure. All Apple Retail stores are company owned (Apple leases the space). Apple currently has 21 foreign retail stores (9 in the UK, 7 in Japan, 4 in Canada, and 1 in Italy). Apple used this wholly owned strategy because it feels it “is able to better control the customer retail experience and attract new customers.” Apparently Apple has no plans to change this strategy (see email message from Apple next slide). Visit: http://www.apple.com/retail/storelist/ Apple’s Attitude Towards Partnering! April 18, 2007 Hello Michael: “We own all of our Apple retail stores and have no plans for franchises or partnering.” We have 21 stores outside the U.S. (7 in Japan, 9 in UK and 4 in Canada and we opened our first store in Italy) out of a total of 177 stores open today. Best regards, Joan Hoover Director, Investor Relations Apple Appendix 4: Starbucks Starbucks use of a joint venture in Japan is discussed in the following slide. Joint Venture: Starbucks in Japan Starbucks entered Japan under a joint venture arrangement in 1995. The joint venture was with Sazaby League, a Japanbased retailer and restaurant operator. The two formed a new company: Starbucks Coffee Japan The joint venture issued stock in Japan and raised about $120 million for financing its stores in Japan. Stock now trades on the Osaka Stock Exchange. First Starbucks opened in Japan in 1996. As of January 2007, there were 666 Starbucks locations in Japan Visit: http://www.starbucks.co.jp/en Appendix 5: Involvement of Private Equity and Hedge Funds in Cross Border M&A Cross Border A&A by Private Equity and Hedge Funds Appendix 6: A review of Investment Policies Affecting FDI As the following slides reveal, governments have liberalized their investment policies in recent years. This liberalization has allowed FDI to acccelerate. Regulatory Changes, 1992-2005 Regulatory Changes, 2005, by Nature and Region, % Appendix 7: Cross Border M&A Activity: 2005 Compared to 2002 and the Ten Largest M&As from 1998 to 2003 Cross Border M&A: Now and Previous Peak Top 10 Cross-Border M&A Deals 1998-2003 Year ($ b) Acquirer 2000 202.8 Vodafone AirTouch PLC Home Target Host U.K. Mannesmann AG Germany 1999 60.3 Vodafone Group PLC U.K. AirTouch U.S. 1998 48.2 British Petroleum Co. U.K. Amoco U.S. 2000 46 France Telecom SA France Orange PLC U.K. 1998 40.5 Daimler-Benz AG Germany Chrysler Corp. U.S. 2000 40.4 Vivendi SA France Seagram Co. LTD Canada 1999 34.6 Zeneca Group PLC U.K. Astra AB Sweden 1999 32.6 Mannesmann AG Germany Orange PLC U.K. 2001 29.4 VoiceStream Wireless Corp U.S. Deutsche Telekom AG Germany 2000 27.2 BP Amoco PLC U.K. ARCO U.S. Appendix 8: Motivation for FDI from the Standpoint of US and Japanese Firms The models used to explain the reason behind US and Japanese FDI differ. The following slides discuss this. Impact of FDI on US Firms Early FDI studies concentrated on the impact of FDI on the value of American firms. Rugman (1980) postulated a firm could maximize its value by internally employing its intangible assets through FDI, rather than licensing the technology to foreign producers. Fatemi (1984) used event study methodology and found positive cumulative abnormal returns of multinational firms around the date of international expansion. Doukas and Travlos (1988), using event study methodology, showed that shares of U.S. firms expanding into a new country experience significant positive abnormal returns at the announcement of FDI. Thus, booth studies concluded that U.S. firms engaged in FDI because of the positive impact on shareholder wealth. Japanese Firm FDI As multinational corporations in other industrialized nations also participated in global FDI, the important question became whether the shareholder wealth American FDI theory was applicable to their companies. The Japanese have long contended that the Japanese model of FDI is different from the American model. Kojima (1973) argued that Japanese firms invest abroad not to maximize shareholder wealth because of because of monopolistic advantages, but instead to seek low-cost labor or other production factors such as natural resources. Ozawa (1979) expanded this argument by suggesting that the main driving forces of Japanese FDI were macro-economic in nature, because Japan had poor natural resources and the Japanese economy relied heavily on exports. Recent empirical evidence (Yamada, 1996; Blonigen,1997 and Lee, 1999) has tended to support the argument that Japanese MNCs behave differently from their counterparts in the Western world when engaging in FDI. Appendix 9: Case Study of Political Risk The following political risk case study is of Coca-Cola in India. It shows how sudden changes in the political environment can adversely affect a foreign firm Coca-Cola and India: Background From the 1950s into the early 1970s, Coca-Cola had operated successfully in India as the country’s leading soft drink company. However, by the mid-1970s, the political environment in India towards non-resident firms had changed dramatically. Coca-Cola in India: 1974-1977 From 1974 to 1977, India’s socialist government (lead by the Janata Party) engaged in a four-year campaign against multinational firms in general and Coca-Cola in particular. In the case of Coca-Cola, the Indian government claimed that the company was taking more money out of the country then putting in and was adversely affecting its domestic soft-drink industry. Coca-Cola and India: 1978 In 1977 the government demanded that Coca-Cola turn over its secret drink formula and sell 60% of its operations to Indian investors or face expulsion. Under India’s Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, foreign companies were required to reduce their equity stake in India to 40% if they wished to remain in India. A year later, after unsuccessful negotiations with the India Government, Coca-Cola left India. In 1989, Pepsi entered the Indian market under an arrangement whereby the Indian Government held 100% of the shares of Pepsi India. Pepsi also agreed to export $5 of locally-made products for every $1 of materials it imported In October, 1993, Coca-Cola returned to India, after the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act was revised in its favor. Appendix 10: Bribery and Global Business These slides discuss the issue of bribery and global business, with focus on the 1977 US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Influencing Governments and Global Business Influencing government officials can take one of two very opposite forms: Legitimate (and legal) lobbying Company (and spokespersons for companies) talking to government policy makers for the purpose of presenting their positions and having governments enact legislation favorable to their company (or industry). Bribery Paying government officials for favors. The U.S. Position on Bribery In 1977, the United States Congress passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). Passage in part resulted from Lockheed Martin Corporation’s bribery of Japanese Government in early 1970s. FCPA makes it illegal for U.S. companies to bribe government officials or political candidates in other countries. A corrupt payment is defined as one made to influence an official's decision. Guilty U.S. firms are subject to fines of up to US$2 million per incident. Officers, directors, employees, and agents are subject to fines of up to US$100,000 and/or imprisonment for up to five years. Other Countries’ Position on Bribery The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) was created in 1960 for the purpose of promoting market economies and democratic governments. One assumed condition of an efficient market economy is that the “playing field” is fair and open. Bribery is not consistent with this. http://www.oecd.org/home/ In 1999, OECD member countries agreed to a Convention Against Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. This OECD Convention would make it a crime to offer, promise or give a bribe to a foreign public official in order to obtain or retain international business deals.