Ch 30 notes

advertisement

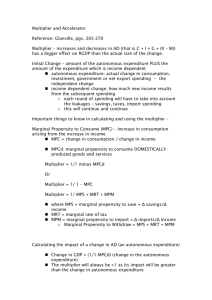

30.1 Expenditure Plans and Real GDP The Keynesian model applies to the very short run in which firms have fixed the prices of their goods and services. As a result, the price level is fixed and so aggregate demand determines real GDP. Expenditure Plans Aggregate expenditure equals consumption expenditure plus investment plus government expenditures on goods and services plus exports minus imports, or C + I + G + NX. Aggregate planned expenditure is equal to planned consumption expenditure plus planned investment plus planned government expenditures on goods and services plus planned exports minus planned imports. In the very short term, planned investment, planned government expenditures, and planned exports are fixed. Planned consumption expenditure and planned imports are not fixed, but depend on aggregate income. An increase in real GDP increases aggregate expenditure and an increase in aggregate expenditure increases real GDP. Autonomous Expenditure and Induced Expenditure The components of aggregate expenditure that do not change when real GDP changes are called autonomous expenditure. The components of aggregate expenditure that change when real GDP changes are called induced expenditure. The Consumption Function The consumption function is the relationship between consumption expenditure and disposable income, other things remaining the same. Disposable income is aggregate income minus taxes plus transfer payments. The figure shows a consumption function. Along the 45 degree line, consumption equals disposable income. When the consumption function is above the 45 degree line, there is dissaving. When the consumption function is below the 45 degree line, there is saving. The consumption expenditure when disposable income is zero, $2 trillion in the figure, is autonomous consumption. Consumption expenditure in excess of this amount is induced consumption. Marginal Propensity to Consume The marginal propensity to consume is the fraction of a change in disposable that is consumed. The MPC is equal to (MPC ) income Change in consumption expenditure Change in disposable income . The MPC is slope of the consumption function, which is 0.67 in the figure. Other Influences on Consumption A change in disposable income leads to a movement along the consumption function. A change in the real interest rate, the buying power of net assets, or expected future disposable income shifts the consumption function. An increase in the buying power of net assets or expected future disposable income and a decrease in the real interest rate increases consumption and shifts the consumption function upward. Imports and Real GDP Imports depend on U.S. real GDP. The marginal propensity to import is the fraction of an Change in imports increase in real GDP that is spent on imports and is equal to . Change in real GDP 30.2 Real GDP (Y ) Equilibrium Expenditure Consumption expenditure (C ) Investment (I ) Government expenditures (G ) Exports (X ) Imports (M ) Aggregate planned expenditure (AE=C+I+G+XM) (trillions of 2000 dollars) 8.0 4.2 2.0 2.0 1.0 0.8 8.4 9.0 5.1 2.0 2.0 1.0 0.9 9.2 10.0 6.0 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 10.0 11.0 6.9 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.1 10.8 Aggregate Planned Expenditure and Real GDP Aggregate planned expenditure, AE, is sum of planned consumption expenditure plus planned investment planned government expenditures on and services plus planned exports minus planned imports. The table above shows the calculation of an aggregate planned expenditure schedule. The shows the resulting AE curve. the plus goods figure Equilibrium Expenditure Equilibrium expenditure is the level of aggregate expenditure that occurs when aggregate planned expenditure equals real GDP. In the figure, equilibrium expenditure is $10 trillion. Convergence to Equilibrium Actual expenditures can differ from planned expenditures because firms do not always sell what they plan to, in which case they have unplanned inventory investment. For instance, a car that is manufactured but not immediately sold is part of that firm’s inventory investment regardless of whether it was planned or not. If aggregate expenditure does not equal its equilibrium, there are forces that lead to convergence. For example, if real GDP exceeds aggregate planned expenditure, firms find their inventories are increasing more than planned. The unplanned inventory accumulation leads firms to cut production so that real GDP decreases, which decreases aggregate planned expenditures. Real GDP still exceeds aggregate planned expenditure, but by less than before. The process continues until real GDP equals aggregate planned expenditure so that there is no unplanned inventory accumulation. 30.3 The Expenditure Multiplier The Basic Idea of the Multiplier The multiplier is the amount by which a change in autonomous expenditure is magnified or multiplied to determine the change in equilibrium expenditure and real GDP. The multiplier exists because a change in autonomous expenditure creates a change in disposable income, which leads to additional changes in induced expenditure and disposable income. The multiplier effect operates for a decrease as well as an increase in autonomous expenditure. The Size of the Multiplier Change in equilibrium expenditure The multiplier equals If there are no imports or income taxes, the multiplier equals Change in autonomous expenditure . 1 . 1 MPC The size of the multiplier depends on the MPC. The smaller the MPC, the smaller the increase in expenditure at each step of the multiplier process and so the smaller the multiplier. The Multiplier, Imports and Income Taxes Imports and income taxes both mean that the increase in expenditure on domestic production will be smaller at each step of the multiplier process and so the multiplier is smaller. 1 When imports and income taxes are included, the multiplier equals . In 1 slope of the AE curve the previous figure, the slope of the AE curve is 0.8, so the multiplier equals 5.0. It is interesting to note that the volatility of real GDP has declined in recent years (since 1984 to be precise). One question is whether this decline is the result of a smaller multiplier or simply a lack of large changes in autonomous expenditure (referred to as “shocks” by economists). No consensus has been reached, although some economists including James Stock and Mark Watson have argued that the reduction is more the consequence of smaller shocks rather than a decrease in the size of the multiplier. Business Cycle Turing Points An unexpected decrease in autonomous expenditure is signaled by a buildup of unplanned inventories. The buildup in inventories sets the multiplier process in motion that decreases aggregate expenditure and real GDP so that a recession follows. An unexpected increase in autonomous expenditure is signaled by an unwanted depletion of inventories. The depletion in inventories sets the multiplier process in motion and an expansion follows. 30.3 The Expenditure Multiplier Deriving the AD Curve from Equilibrium Expenditure The AE curve is the relationship between aggregate planned expenditures and real GDP, all other influences (such as the price level) remaining the same. The AD curve is the relationship between the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded and the price level. The AD curve is derived from the AE model. A rise in the price level decreases aggregate planned expenditure. So, as shown in the figure to the left, a rise in the price level from 120 to 140 decreases aggregate planned expenditure and shifts the AE curve downward from AE0 to AE1. In the figure, equilibrium expenditure decreases to $9 trillion. The diagram to the right shows that when the price level rises from 120 to 140, there is a movement along the AD curve from point a to point b. The aggregate quantity of real GDP demanded decreases from $11 trillion (which is the initial equilibrium expenditure in the AE diagram to the left) to $9 trillion (which is the new equilibrium expenditure along AE1 in the AE diagram to the left).